The capitalist mode of production, which arose as successor to the feudal mode of production, is based upon exploitation of the class of wage-workers by the class of capitalists. To understand the essence of the capitalist mode of production one must bear in mind, first and foremost, that the capitalist system has commodity production as its foundation: under capitalism everything takes the form of a commodity and the principle of buying and selling prevails everywhere.

Commodity production is older, than capitalist production. It existed in slave-owning society and under feudalism. In the period when feudalism was breaking down, simple commodity production served as the basis for the rise of capitalist production.

Simple commodity production presupposes, first, the social division of labour, under which individual producers specialise in making particular products, and, second, the existence of private property in the means of production and in the products of labour.

The simple commodity production of craftsmen and peasants is distinguished from capitalist commodity production by the fact that it is based upon the personal labour of the commodity producer. Yet fundamentally it is similar in kind to capitalist production, in so far as its foundation is private property in the means of production. Private ownership inevitably gives rise to competition between the commodity producers, which leads to the enrichment of a minority and the ruin of the majority. Thus, petty commodity production serves as the point of departure for the rise and development of capitalist relations.

Under capitalism commodity production becomes dominant and universal. The exchange of commodities, Lenin wrote, appears as “the simplest, most ordinary, fundamental, most common and everyday relation of bourgeois (commodity) society, a relation that is encountered thousands of millions of times.” (Lenin, “On Dialectics”, Marx-Engels-Marxism, 1951, English edition, p. 334.)

A commodity is a thing which, first, satisfies some human demand and, second, is produced not for personal consumption but for exchange.

The utility of a thing, the characteristics thanks to which it is able to satisfy some human demand, makes the thing a use-value. A use-value can either directly satisfy an individual human demand or else serve as a means of production of material wealth. For instance, bread satisfies a demand as food and cloth as clothing, while the use-value of a loom consists in the fact that cloth is made with its help. In the course of historical development, man continually discovers fresh useful characteristics in things and fresh ways of using them.

Use-value is possessed by many things which have not in any way been created by human labour, such as, for example, spring-water or the fruits of wild trees. But not everything which has use-value is a commodity. For a thing to become a commodity it must be a product of labour produced for sale. Use-value forms the material substance of wealth, whatever its social form may be. In a commodity economy, use-value is the depository of the exchange-value of a commodity. Exchange-value appears first of all as the quantitative relationship in which use-values of one kind are exchanged for use-values of another kind. For example, one axe is exchanged for 20 kilogrammes of grain. In this quantitative relationship between the commodities exchanged is expressed also their exchange-value. Commodities are treated as equivalent to each other in definite quantities, consequently they must have a common basis. This basis cannot be any of the natural properties of commodities-their weight, size, shape, etc. The natural properties of commodities determine their utility and their use-value, a necessary condition for exchange is difference between the use-values of the commodities to be exchanged. No one will exchange commodities which are identical, such as wheat for wheat, or sugar for sugar. The use-values of different commodities, being different qualitatively, are incommensurable quantitatively.

Commodities of different kinds have only one characteristic in common which makes it possible to compare them for purposes of exchange, and it is that they are all products of labour. Underlying the equivalence of two commodities which are exchanged against each other is the social labour expended in producing them. When a commodity producer brings an axe to market in order to exchanger it he finds that for his axe he can get 20 kilogrammes of grain. This means that the axe is worth the same amount of social labour as 20 kilogrammes of grain are worth. Value is the social labour of commodity producers embodied in a commodity.

That the value of commodities embodies the social labour expended in producing them is borne out by some generally known facts. Material wealth which is useful in itself, but requires no expenditure of labour for its production, has no value-e.g., the air. Material wealth which requires a large expenditure of labour has a high value-e.g., gold, diamonds. Many commodities which at one time were costly have become cheaper as the development of technique has reduced the amount of labour needed to produce them. Changes in the amount of labour expended in producing commodities are usually reflected in the quantitative relationship between these commodities when exchanged, i.e., in their exchange-value. It follows from all this that the exchange-value of a commodity is the form in which its value manifests itself.

Hidden behind the exchange of commodities is the social division of labour between the persons who are the owners of these commodities. When commodity producers compare different commodities, one with another, in so doing they are comparing their different kinds of labour. Thus, value expresses the production-relations between commodity producers. These relations manifest themselves in the exchange of commodities.

A commodity has a two-fold character: in one aspect it is a use-value and in another it is a value. The two-fold character of the commodity is caused by the two-fold nature of the labour embodied in the commodity. The kinds of labour are just as various as the use-values which are produced. The labour of a joiner is qualitatively different from that of a tailor, a shoemaker, etc. The different kinds of labour are distinguished one from another by their aims, methods, tools and, finally, their results. The joiner does his work with an axe, a saw and a plane and makes wooden articles: tables, chairs, cupboards; the tailor makes clothes, using a sewing machine, scissors and a needle. Thus, in each use-value a definite kind of labour is embodied: in a table-the joiner’s labour, in a suit-the tailor’s labour, in a pair of shoes-the shoemaker’s labour, etc. Labour expended in a definite form is concrete labour. Concrete labour creates the use-value of a commodity.

In the course of exchange, commodities of the most various kinds, created by different kinds of concrete labour, are compared together and measured on a common footing. Consequently, behind the different concrete forms of labour there is hidden something common, something inherent in every form of labour. Both the joiner’s labour and the tailor’s, despite the qualitative difference between these forms of labour, constitute a productive expenditure of human brains, nerves, muscles, etc., and in this sense are homogeneous human labour, labour in general. The labour of commodity producers, considered as expenditure of human labour-power generally, without regard to its concrete form, is abstract labour. Abstract labour forms the value of a commodity.

Abstract and concrete labour are two aspects of the labour embodied in a commodity.

“On the one hand, all labour is, speaking physiologically, an expenditure of human labour-power and in its character of identical abstract human labour, it creates and forms the value of commodities. On the other hand, all labour is the expenditure of human labour-power in a special form and with a definite aim, and in this, its character of concrete useful labour, it produces use-values.” (Marx, Capital, Kerr edition, vol. I, p. 54.)

In a society in which private property in the means of production prevails, the two-fold character of the labour embodied in a commodity reflects the contradiction between the private and social labour of the commodity producers. Private ownership of the means of production separates people, makes the labour of the individual commodity producer his own private affair. Each commodity producer conducts his enterprise separately from the rest. The labour of the separate workers is not concerted or co-ordinated on the scale of society as a whole. But, from another angle, the social division of labour means that all-round connections exist between the producers, who are working for each other. The more labour is divided in society and the more varied are the products manufactured by the separate producers, the more extensive is the mutual dependence of the latter. Consequently, the labour of each separate commodity producer is essentially social labour and forms a particle of the labour of society as a whole. Commodities, which are products of various kinds of particular, concrete labour, are at the same time also products of human labour in general, abstract labour.

It follows that the contradiction of commodity production consists in the labour of commodity producers, which is directly the private affair of each one of them, having at the same time a social character. Owing to the isolation of the commodity products one from another, the social character of their labour in the process of production remains hidden. It finds expression only in the process of exchange, when the commodity comes on to the market and is exchanged against another commodity. Only in the process of exchange is it revealed whether the labour of a particular commodity producer is needed by society and whether it will receive social recognition.

Abstract labour, which forms the value of a commodity, is an historical category, a specific form of social labour belonging to commodity economy only. In natural economy men produce their products not for exchange but for personal consumption, so that the social character of their labour appears directly in concrete form. For example, when a feudal lord extracted surplus product from serf-peasants in the form of labour-rent or rent in kind, he appropriated their labour directly in the form of labour services or definite products. In these circumstances social labour did not assume the form of abstract labour. In commodity production, products are produced not for personal consumption but for sale. The social character of labour is here expressed by means of the comparison of one commodity with another, and this comparison takes place through the reducing of concrete forms of labour to the abstract labour which forms the value of a commodity. This process takes place spontaneously, without any sort of common plan, behind the backs of the commodity producers.

The magnitude of the value of a commodity is determined by labour-time. The more labour-time is needed to produce a given commodity, the higher is its value. Of course, the individual commodity producers work in varying conditions and expend varying amounts of labour-time in the production of one and the same kind of commodity. Does this mean that the more idle the worker, or the less favourable the conditions in which he is working, the higher the value of the commodity produced by him? No, it does not mean that. The magnitude of the value of a commodity is determined not by the individual labour-time expended by a particular commodity producer in producing a commodity, but by the socially-necessary labour-time.

Socially-necessary labour-time is the time needed for the making of any commodity under average social conditions of production, i.e., with the average level of technique and average skill and intensity of labour. It corresponds to the conditions of production under which the greatest bulk of goods of a particular kind are produced. Socially-necessary labour-time changes as a result of the growth of the productivity of labour.

The productivity of labour is expressed in the amount of products created in a given unit of labour-time. The productivity of labour grows as a result of the improvement or fuller utilisation of the instruments of production, the development of science, the increase in the worker’s skill, the rationalisation of work, and other improvements in the production process. To a greater or less extent it is also dependent on natural conditions. The higher the productivity of labour, the less the time needed for the production of a unit of the given commodity and the lower the value of this commodity.

The intensity of labour must be distinguished from the productivity of labour. The intensity of labour is determined by the amount of labour expended in a unit of time. A growth in the intensity of labour means an increase in the expenditure of labour in one and the same interval of time. More intensive labour embodies itself in a greater quantity of products and creates a greater value in a given unit of time, as compared with less intensive labour.

Workers of varying skill take part in the production of commodities. The labour of a worker who has had no special training is simple labour. Labour which requires special training is complex or skilled labour.

Complex labour creates value of greater magnitude than is created by simple labour in the same unit of time. Into the value of a commodity created by complex labour there enters also part of the labour expended on the worker’s training, on raising his degree of skill. Complex; labour is equivalent to multiplied simple labour; one hour of complex labour is equal to several hours of simple labour. The reduction of various forms of complex labour to simple labour takes place spontaneously under commodity production based on private property. The magnitude of the value of a commodity is determined by the socially-necessary amount of simple labour.

The value of a commodity is created by labour in the process of production, but it can manifest itself only through the comparison of one commodity with another in the process of exchange, i.e., through exchange-value.

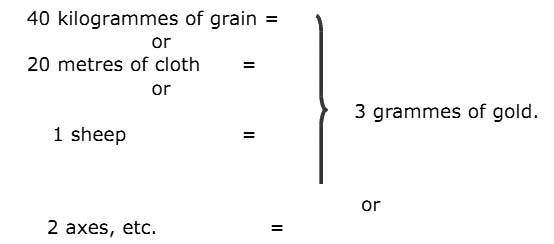

The simplest form of value is the expression of the value of one commodity in terms of another commodity: e.g., one axe=2.0 kilogrammes of grain. Let us examine this form.

In this case, the value of the axe is expressed in terms of grain. The grain serves as a means of expressing the value of the axe. It is possible to express the value of the axe in the use-value of grain only because labour is expended both in the production of the grain and in that of the axe. Behind the equality of these commodities is concealed the equal expenditure of labour in producing them. A commodity which expresses its value in another commodity (in our example, the axe), has a relative form of value. A commodity the use-value of which serves as the means of expressing the value of another commodity (in our example, the grain), has an equivalent form. The grain is the equivalent of (is worth) the other commodity, viz., the axe.

The use-value of one commodity, grain, thus becomes the form in which the value of another commodity, the axe, is expressed.

In the beginning, exchange, which originated already in primitive society, was of a casual nature and took place in the form of direct exchange of one product for another. To this stage in the development of exchange corresponds the elementary or accidental form of value:

1 axe = 20 kilogrammes of grain.

Under the elementary form of value, the value of an axe can be expressed only in the use-value of a single commodity; in the given example, grain.

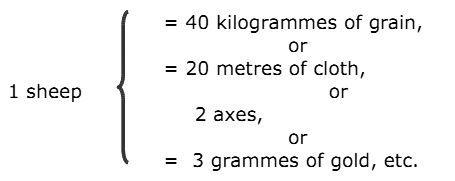

With the rise of the first major social division of labour-the separation of pastoral tribes-from the general mass of tribes exchange becomes more regular. Certain tribes, e.g., the cattle-raising ones, begin to produce a surplus of cattle products, which they exchange for products of agriculture or handicraft which they lack. To this level of the development of exchange corresponds the total or expanded form of value. There now take part in exchange not two but a whole series of commodities:

In this case the commodity’s value is expressed in the use-value not of a single commodity but of a number of commodities, all playing the part of equivalent. In addition, the quantitative correlations in which the commodities are exchanged, acquire a more constant character. At this stage, however, the direct exchange of one commodity for another is retained.

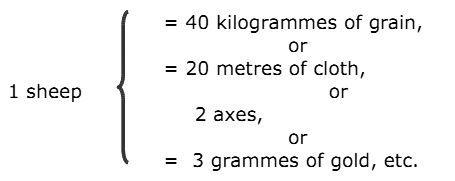

With the further development of the social division of labour and of commodity production, the form of direct exchange of one commodity far another becomes inadequate. Difficulties arise in the process of exchange, engendered by the growth of the contradictions of commodity production, contradictions between individual and social labour, between the use-value and the value of a commodity. With increasing frequency the situation occurs when, for example, the owner of some shoes wants an axe, but the use-value of the shoes prevents exchange being effected, because the owner of an axe wants not shoes but grain: it is not possible for these tw6 commodity owners to effect a transaction. When this happens the owner of shoes exchanges his shoes for that commodity which is exchanged more often than any other and which everybody accepts most readily-a sheep, say-and then exchanges this sheep for the axe which he wants. The owner of the axe, having received in exchange for it a sheep, exchanges this for grain. This is how the contradictions of direct exchange are solved. The direct exchange of one commodity for another gradually disappears. From among the commodities one becomes singled out-e.g., livestock-for which all commodities begin to be exchanged. To this stage in the development of exchange corresponds the general form of value:

It is a characteristic of the general form of value that all commodities begin to be exchanged for a commodity which plays the role of universal equivalent. At this stage, however, the role of universal equivalent had still not become attached to any single commodity. In different places the role of universal equivalent was played by different commodities. In some places it was livestock, in others furs, in yet others salt, and so on.

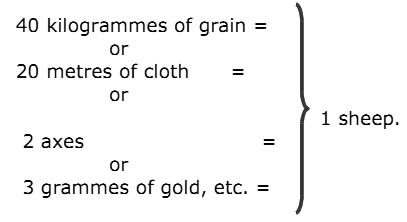

The further growth of the productive forces, the transition to metal tools, the rise of the second major division of labour -the separation of handicraft from agriculture-led to the further development of commodity production and the widening of the market. The abundance of different commodities playing the role of universal equivalent came into contradiction with the needs of the growing market, which required transition to a single equivalent.

When the role of universal equivalent had become attached to one commodity, the money form of value appeared. The role of money has been taken by various metals, but eventually it became consolidated in the precious metals, gold and silver. In silver and gold are particularly expressed all the advantages of metals which make them more suitable than anything else to fulfil the function of money: homegeneity, divisibility, durability and insignificant size and weight combined with great value. Therefore the role of money became firmly connected with the precious metals, and in the long run with gold. The money form of value can be depicted like this:

Under the money form of value, the value of every commodity is expressed in the use-value of a single commodity, which has become the universal equivalent.

Money thus arose as a result of a long process of development of exchange and of forms of value. With the rise of money a polarisation took place in the world of commodities-at one pole remained the ordinary commodities, while to the other pole went the commodity which played the role of money. Now all commodities begin to express their value in the money; commodity. Consequently, money appears, in contradiction to all other commodities, as the general embodiment of value the universal equivalent. Money possesses the property of being directly exchangeable for any commodity and so serves as the means of satisfying all the requirements of the commodity owners, whereas all other commodities can satisfy only one or other of their requirements-e.g., bread, clothing, etc.

Consequently, money is the commodity which is the universal equivalent of all commodities; it embodies social labour and expresses the production relations between the’ commodity producers.

As commodity production extends so the functions fulfilled by money expand. In developed commodity production money serves as:

(1) the measure of value, (2) the medium of circulation, (3) the means of accumulation, (4) the means of payment and (5) world-wide currency.

The fundamental function of money consists in serving as the measure of value of commodities. With the aid of money the individual labour of a commodity producer finds social expression and the spontaneous calculation and measurement of the values of all commodities is effected. The value of a commodity cannot be directly expressed in labour-time, since under conditions in which the private commodity producers operate in isolation and separation one from another it is impossible to determine the amount of labour which not any particular commodity producer but society as a whole expends in the production of any particular commodity. For this reason the value of a commodity can be expressed only indirectly, by way of the equating of the commodity with money in the process of exchange.

To fulfil the function of measure of value, money must itself be a commodity and possess value. Just as the weights of bodies can be measured only by means of scales which themselves possess weights, so the value of a commodity can be measured only by means of a commodity which possesses value.

Measurement of the value of commodities by means of gold occurs even before a given commodity is exchanged for money. To express the value of commodities in money it is not necessary to have cash in one’s hand. In fixing a definite price for a commodity, its owner mentally (or, as Marx puts it, ideally) expresses the commodity’s value in gold. This is possible thanks to the fact that there exists in reality a definite correlation between the value of gold and the value of the given commodity; the basis for this correlation is provided by the socially-necessary labour which is expended in producing them.

A commodity’s value expressed in money is called its price. Price is the monetary expression of the value of a commodity. Commodities express their value indefinite amounts of silver or gold. These amounts of the money commodity must themselves in their turn be measured. This gives rise to the need for a unit of measurement of money. This unit consists of a definite amount, by weight, of the metal used for money.

In Britain, for example, the money unit is called the pound sterling; at one time it corresponded to a pound of silver. Later, money units ceased to coincide with units of weight. This occurred as a result of the importation of foreign coins, of the going over from silver to gold, and especially in consequence of the debasement of coins by governments, which gradually reduced their weight. For convenience of measurement monetary units are divided into aliquot parts: the rouble into 100 kopeks, the dollar into 100 cents, the franc into 100 centimes, etc.

The unit of money and its parts provide the standard of price. As a standard of price money plays a role completely different from when it serves as a measure of value. As a measure of value money measures the value of other commodities, but as a standard of price it measures the quantity of the money metal itself. The value of the money commodity varies with changes in the amount of labour socially necessary for its production. Changes in the value of gold are not reflected in its function as a standard of price. However much the value of gold may change, a dollar is still worth a hundred times as much as a cent.

The State can alter the gold content of the money unit, but it is not in a position to vary the value relationship between gold and other commodities. Should the State reduce the amount of gold contained in the money unit, i.e., lower its gold content, the market would react to this by a rise in prices, and the value of a commodity would be expressed, as before, in that quantity of gold which corresponded to the labour expended in producing the commodity in question. All that would happen would be that now a larger number of monetary units than before would be needed to express the same quantity of gold.

The prices of commodities may rise or fall under the influence of changes either in the value of commodities or in the value of gold. The value of gold, as of every commodity, depends on the productivity of labour. Thus, the discovery of America, with its rich gold-fields, led to a price-revolution in Europe between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Gold was obtained in America with less labour than in Europe. The influx into Europe of the cheaper American gold brought about a general rise in prices.

Money fulfils the function of circulation medium. The exchanging of commodities effected with the aid of money is called commodity circulation. The circulation of commodities is inseparably bound up with the circulation of money itself: when a commodity passes from the hands of the seller into those of the buyer, money passes from the hands of the buyer into those of the seller. Money’s function as circulation medium consists in its playing the part of intermediary in the circulation process of commodities. To carry out this function real money must be actually present.

At first, when commodities were exchanged, money figured directly in the form of bars of silver or gold. This led to certain difficulties: it was necessary to weigh the money metal, to break it up into small pieces and to carry out assays. Gradually bars of the money metal gave place to coins. A coin is a piece of metal of definite shape, weight and denomination, which serves as a medium of circulation. The minting of money was concentrated in the hands of the State.

During the process of circulation, coins become worn by use and lose part of their value. The practice of monetary circulation showed that worn coins could fulfil the function of circulation medium equally as well as coins of full value. The reason for this was that money when acting as a circulation medium plays only a fleeting role. As a rule, the seller of a commodity accepts money in exchange for it so as to buy another commodity with this money. Consequently, money acting as circulation medium need not necessarily possess its proper value.

Taking into account the practice of the circulation of worn coins, governments began consciously to debase the coinage, to reduce its weight, to lower the standard of assay of the money metal without changing the nominal value of coins, i.e., the number of monetary units marked upon them. Coins were transformed more and more into symbols of value, tokens of money. Their actual values are very much less than they nominally appear to be.

The splitting of the category “commodities” into commodities and money heralds a development of the contradictions of commodity production. When one commodity is directly exchanged for another, each transaction is of an isolated nature; selling is not separated from buying. It is another matter when exchange is carried on by mean of money, i.e., when commodity circulation arises. Now exchange presupposes an all-round connection between commodity producers and a ceaseless interweaving of transactions among them. It opens up the possibility of a separation between buying and selling. A commodity producer can sell his commodity and retain for the time being the money which he receives for it. When many commodity producers sell without buying, a hold-up in the sale of commodities Can come about. Thus, even simple commodity circulation contains in germ the possibility of crises. For this possibility to be transformed into inevitability, however, a number of conditions are needed which appear only with the advance to the capitalist mode of production.

Money fulfils the function of means of accumulation or means of forming hoards. Money is transformed into a hoard when it is withdrawn from circulation. As money can always be transformed into any commodity, it is the universal equivalent of wealth. It can be kept in any quantity. Commodity producers accumulate money, for example, in order to buy means of production or as savings. With the development of commodity production the power of money grows. All this gives rise to a passion for saving money, to the formation of hoards. The function of a hoard can be fulfilled only by money of full value: gold and silver coins, bars of gold and. silver, and also articles made of gold and silver. When gold or silver coins are serving as money, they spontaneously adapt themselves in amount t-a the requirements of commodity circulation. When the production of commodities declines and commodity circulation shrinks, some of the gold coins disappear from circulation and are transferred into hoards. When production extends and commodity circulation grows, these coins reappear in circulation.

Money fulfils the function of means of payment. Money figures as a means of payment in cases when the buying and selling of a commodity is carried out on credit, i.e., with. the payment deferred. When a commodity is bought on credit the transfer of the commodity from the seller’s hands to the buyer’s is effected without immediate payment by the purchaser. When the time comes fori the purchased commodity to be paid for, money is paid by the buyer to the seller without any’ transfer of a commodity, this having taken place earlier. Money serves as a means of payment also in the payment of taxes, rent, etc.

The functioning of money as a means of payment reflects the further development of the contradictions of commodity production. The links between the separate commodity producers become more extensive and their dependence upon each other increases. The buyer now becomes a debtor and the seller is transformed into a creditor. When many commodity owners are buying commodities on credit, the failure of one or a number of debtors to honour in due time their promises to pay can react upon a whole series of obligations to pay, and lead to the bankruptcy of a number of commodity owners who are linked together by credit relationships. Thus the possibility of crises, which is already inherent in the function of money as circulation medium, is intensified.

Examination of the function of money as circulation medium and as means of payment enables us to see clearly the law which determines the amount of money needed for the circulation of commodities.

Commodities are bought and sold. in many places at the same time. The amount of money needed for circulation in a given period depends, first of all, on the total of the prices of the commodities in circulation, which in turn depends on the quantity of commodities and the price of each separate commodity. In addition, the velocity with which money moves around must be taken into account. The more rapidly money moves, the less of it is needed for circulation, and vice versa. If, for example, in. the course of a given period-a year, say-,commodities are sold at a total price of 1,000 million dollars, and each dollar moves five times, on the average, then for the circulation of the whole mass of commodities 200 million dollars are needed.

Thanks to the credit which commodity producers grant each other, the need for money is reduced by the total of the prices of commodities which are sold on credit and by the total of payments which mutually cancel out. Ready money is needed only for the settlement of those debt obligations the time to meet which has arrived.

Thus, the law of the circulation of money is this: the amount of money needed for the circulation of commodities must equal the total of the prices of all commodities, divided by the average turnover of money units of the same denomination. Furthermore, from the total of the prices of all commodities must be deducted the total of the prices of all commodities sold on credit and the sum of mutually-cancelling payments, and to it must be added the total of payments the time to settle which has come round.

This law applies universally to all social formations where commodity production and circulation take place.

Finally, money plays the role of world-wide currency in circulation between different countries. The role of universal money cannot be played by coins of less than full value or by paper money. On the world market money abandons the form of coins and appears in its original aspect-bars of precious metal. On the world market, in circulation between countries, gold is the universal purchasing medium for payment for commodities imported into one country from another, the universal means of payment for clearing international debts, for paying interest on foreign loans and other obligations, and the universal embodiment of social wealth when this is transferred from one country to another in monetary form, e.g., when money capital is exported from one country to another for the purpose of depositing it in foreign banks, for making loans, or for the payment of contributions by a conquered country to a victorious one, etc.

The development of the function of money expresses the growth of commodity production and its contradictions. In social formations based on the exploitations of man by man money bears a class character, serving as the means of appropriating the labour of others. It played this part in slave-owning society and in feudal society. As we shall see below, the role of money as an instrument of exploitation attained its highest development in capitalist society.

Under conditions of developed commodity production, paper money is often used instead of gold coins. The issue of paper money was engendered by the practice of the circulation of worn and devalued coins which had become transformed into symbols of gold, symbols of money.

Paper money means money tokens issued by the State, which people are obliged to accept instead of gold so far as its function as circulation medium is concerned. Paper money has no value of its own. For this reason it cannot fulfil the function of measure of the value of commodities. However much paper money may be issued, it represents only the value of that quantity of gold which is necessary for commodity circulation to be maintained. Paper money is not accepted in exchange for gold.

If paper money is issued in accordance with the amount of gold needed for circulation, the purchasing power of paper money, i.e., the amount of commodities which it can buy, coincides with the purchasing power of gold money. But usually the State issues paper money to cover its expenses, especially in wartime, during crises or other emergencies, without regard to the needs of commodity circulation.

When the production and circulation of commodities are restricted or when an exceptional amount of paper money is issued, the latter is found to be in excess of the quantity of gold needed for circulation. Money has been issued, let us say, to an extent double what is needed. In such a case, each unit of paper money (dollar, mark, franc, etc.) will represent half the quantity of gold, i.e., the paper will depreciate by half.

The first attempts to issue paper money took place in China as far back as the twelfth century; paper money was issued in America in 16901and in France in 1716; Britain began to issue paper money at the time of the Napoleonic Wars. In Russia paper money was first issued in Catherine II’s reign.

An extraordinarily large issue of paper money, leading to its depreciation and used by the ruling classes for the purpose of transferring the burden of State expenditure on to the backs of the working masses and increasing their exploitation; is called inflation. Inflation, which gives rise to an increase in the cost of goods, bears heaviest upon the working people, because the wages and salaries of the workers lag behind the rise in prices. Capitalists and landlords benefit from inflation, owing above all to the fall in the real wages of industrial and agricultural workers. Inflation benefits those capitalists who export their commodities. As a result of the fall in real wages and the reduction thereby of the costs of production of commodities it becomes possible for them to compete successfully with foreign capitalists and landlords and increase the. sale of their commodities.

In commodity production based on private property, the production of commodities is carried out by separate private commodity producers. A competitive struggle goes on between these commodity producers. Each one tries to push the others aside and to maintain and extend his own position in the market. Production proceeds without any sort of general plan. Each one produces on his own account, regardless of the others; nobody knows what the demand is for the commodity which he is producing or how many other commodity producers are engaged in producing the same commodity, whether he will be able to find a market for his commodity or whether he will be reimbursed for the labour he has expended. With the development of commodity production the power exercised by the market over the commodity producers becomes ever greater.

This means that in commodity production based on private ownership of the means of production there operates the economic law of competition and anarchy of production. This law expresses the spontaneous nature of production and exchange, the struggle between private commodity producers for more advantageous conditions of production and sale of goods.

Under the conditions of anarchy of production which reign in commodity production based on private property, the law of value appears as the spontaneous regulator of production, acting through market-competition.

The law of value is an economic law of commodity production, by which the exchange of commodities is effected in accordance with the amount of socially-necessary labour expended on their production.

The law of value regulates the distribution of social labour and means of production among different branches of commodity economy spontaneously, through the price mechanism. Under the influence of fluctuations in the relationship of supply and demand the prices of commodities continually diverge either above or below their value. Divergences of prices from values are not a result of some defect in the operation of the law of value, but, on the contrary, are the only possible way in which it can become effective. In a society in which production is in the hands of private owners, working blindly, only the spontaneous fluctuations of prices on the market inform the commodity producers whether they have produced goods in excess of the effective demand by the population or have not produced sufficient to meet it. Only the spontaneous fluctuations of prices around values oblige commodity producers to extend or restrict the production of particular commodities. Under the influence of price-fluctuations, commodity producers rush into those branches which appear most profitable at the given moment because the prices of commodities are higher than their values, and quit those branches where the prices of commodities are lower than their values.

The operation of the law of value conditions the development of the productive forces of commodity economy. As we have seen, the magnitude of the value of a commodity is determined by socially-necessary labour-time. The commodity producers who are the first to introduce a higher technique produce their commodities at reduced cost, in comparison with that which is socially-necessary, but sell these commodities at the prices which correspond to the socially-necessary labour. When they sell their commodities they receive a surplus of money arid grow rich. This impels the remaining commodity producers to make technical improvements in their own enterprises. Thus, as a result of the separate actions of separate commodity producers, each striving for his own private advantages, progress takes place in technique and the productive forces of society are developed.

As a result of competition and anarchy of production, the distribution of labour and means of production between the various branches of economy and the development of the forces of production are accomplished in a commodity economy at the price of great waste of social labour, and lead to the contradictions of this economy becoming more and more acute.

In conditions of commodity production based on private property, the operation of the law of value leads to the rise and development of capitalist relations. Spontaneous fluctuations of market prices around values, and divergences of individual labour costs from the socially-necessary labour which determines the magnitude of the value of a commodity, intensify the economic inequality of the commodity producers and the struggle among them. This competitive struggle leads to some commodity producers being ruined and transformed into proletarians while others are enriched and become capitalists. The operation of the law of value thus brings about a differentiation among the commodity producers. “Small production engenders capitalism and the bourgeoisie continuously, daily, hourly, spontaneously and on a mass scale.” (Lenin, ‘‘‘Left-wing’ Communism, an Infantile Disorder”, Selected Works, 1951, English edition, vol. II, Pt. 2, p. 344.)

In conditions of commodity production based on private ownership of the means of production, the social link between people which exists in the production process makes its appearance only through the medium of exchange of commodities. The fate of the commodity producers is found to be closely connected with the fate of the commodities which they create. The prices of commodities continually change, independently of people’s will or consciousness, and yet the level of prices is often a matter of life and death for the commodity producers.

Relations between things conceal the social relations between people. Thus, though the value of a commodity expresses the social relationship between commodity producers, it appears as a kind of natural property of the commodity, like, say, its colour or its weight. “It is a definite social relation between men,” wrote Marx, “that assumes, in their eyes, the fantastic form of a relation between things.” (K. Marx, Capital, Kerr edition, vol. I, p. 83.)

In this way, in a commodity economy based on private property, the production-relations between people inevitably appear as relations between things (commodities). In this transmutation of production-relations between persons into relations between things is inherent also the commodity fetishism which is characteristic of commodity production.2

Commodity fetishism is displayed with especial clarity in money. In commodity economy money is a tremendous force, giving power over men. Everything can be bought for money. It comes to seem that this capacity to buy anything and everything is a natural property of gold, whereas in reality it is a result of definite social relations.

Commodity fetishism has deep roots in commodity production, in which the labour of a commodity producer appears directly as private labour, and its social character is revealed only in the exchange of commodities. Only when private property in the means of production is abolished does commodity fetishism disappear.

(1) The point of departure for the rise of capitalism was the simple commodity production of craftsmen and peasants. Simple commodity production differs from capitalism in that it is based upon the individual labour of the commodity producer. At the same time it belongs fundamentally to the same type as capitalist production, in as much as its foundation is private ownership of the means of production. Under capitalism, when not only the products of labour, but labour power too becomes a commodity, commodity production acquires a dominant, universal character.

(2) A commodity is a product which is made for exchange, it appears from one angle as a use-value and from the other as a value. The labour which creates a commodity possesses a dual character. Concrete labour is labour expended in a definite form; It creates the use-value of a commodity. Abstract labour is the expenditure of human labour power in general; It creates the value of a commodity.

(3) Value is the social labour of the commodity producers embodied in a commodity. Value is an historical category which belongs only to commodity economy. The magnitude of the value of a commodity is determined by the labour which is socially-necessary for its production. The contradiction in simple commodity economy consists in the fact that the commodity producers’ labour, which is directly their own private affair, bears at the same time a social character.

(4) The development of the contradictions of commodity production leads to one commodity spontaneously being singled out from the rest and becoming money. Money appears as the commodity which plays the role of universal equivalent. Money fulfils the following functions: (1) measure of value, (2) medium of circulation, (3) means of accumulation, (4) means of payment, and (5) world-wide currency.

(5) With the growth of the circulation of money, paper money arises. Paper money, which lacks any value of its own acts as a token for metallic money and replaces it as the circulation medium. An exceptionally large issue of paper money, causing its depreciation (inflation) leads to a lowering of the standard of life of the working people.

(6) In a commodity economy based on private property in the means of production, the law of value is the spontaneous regulator of the distribution of social labour between branches of production. The operation of the law of value causes a differentiation among the petty commodity producers and the development of capitalist relations.

1.In Massachusetts, then a British colony. Editor, English edition.

2. The transmutation of production-relations between persons into relations between things, characteristic of commodity production, is called “commodity fetishism” because of its resemblance to the religious fetishism which is involved in the deification by primitive men of objects which they themselves have made.