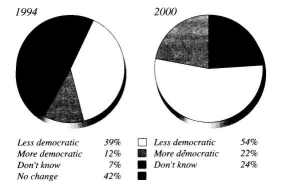

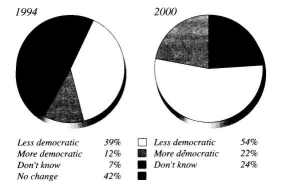

Table 1: LOSING FAITH IN DEMOCRACY

Do you think this country is getting more or less democratic?

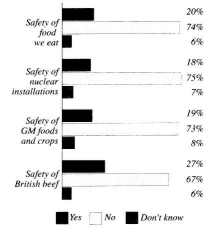

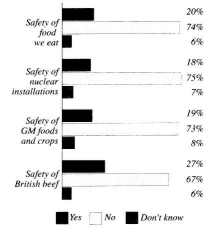

Do you trust ministers and their advisory committees to tell the truth about each of the following?

John Rees Archive | ETOL Main Page

From International Socialism 2:90, Spring 2001:

Copyright © International Socialism.

Copied with thanks from the International Socialism Archive.

Marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

This is a time of change. Old political patterns are being transformed. Ossified relationships are breaking up and new ones are taking their place. New forces are entering the line, revitalising the veterans. It is all long, long overdue.

For 20 years socialists and working class activists have seen trade unionism, welfare provision and left wing consciousness in retreat. We have fought, sometimes in battles on the epic scale of the 1984–1985 miners’ strike, but mostly we have lost. In the 1990s the tide began to turn, at first slowly, almost imperceptibly. Attitudes began to shift. The mania for the market subsided. The poll tax was defeated. Thatcher and Reagan passed into unbalanced retirement. The transformation in popular attitudes eventually registered in a massive electoral defeat for the Tories, part of a European-wide pattern.

Then, as so often happens, these small changes became a change in the look of the whole political landscape. The signal was Seattle. The tens of thousands who demonstrated against the World Trade Organisation in Seattle in November 1999 provided a public language in which it could all be summed up, the language of anti-capitalism. Seattle popularised and legitimised direct action in a way not seen since the 1970s. We have begun to move forward again. Many difficult decisions, many hard battles, and no doubt still some serious defeats, lie ahead. But, for all that, we have begun to move forward again. We have reached a turning point in the class struggle.

This article looks at three decisive sectors in which the struggle is reviving: the anti-capitalist mobilisations, the industrial struggle and the electoral battle. It examines the strategy, tactics and form of party organisation that is necessary for socialists to be effective in strengthening these movements.

There has been no year since the 1970s when we could look back over a 12-month period and see an unbroken chain of international demonstrations like those which began in Seattle, and carried on through Washington and Los Angeles in the United States, Windsor in Canada, Melbourne in Australia, Millau and Nice in France, Prague in the Czech Republic, and Davos in Switzerland.

What is it about these demonstrations which mark a watershed? The first and most obvious point is that these demonstrations identify the capitalist system as the enemy. Even when the question which motivates a particular group of protesters seems like a single issue – whether it be genetically modified foods, destructive dam projects in Turkey or India, or ‘unfair’ labour laws – it often turns out that they see multinational corporations, the global market and the drive for profit as the source of the problem. Hence the most popular slogans of the movement: ‘People before profit’ and ‘Our world is not for sale’.

In a report which could have been written about any of the anti-capitalist demonstrations of the last year but was actually written about the protests at President Bush’s inauguration in January 2001, the Washington Post said:

The activists sometimes confound onlookers with the diversity of their concerns, from the environment and civil rights to Third World debt and corporate power. It’s all the same struggle, they say ... ‘We are all united behind a fear and loathing of corporate control in our country,’ says David Levy, 43, a think tank policy researcher ... ‘The government is for sale, and big business bought it.’

It is specifically the global capitalist system that these demonstrators have in their sights. The Washington Post report continues:

The international finance and trade bodies seek to make the world profitable for the same corporations that are running the show in US politics, the demonstrators say ... Framing the issues in this way has allowed disparate causes to unite against common enemies. Save the rainforest and anti-sweatshop activists, for example, stand against the same trade and development policies that might boost corporate investment in a poor country engaged in selling off its natural resources. Global capitalism is unjust and ineffective in these situations, the activists say. [1]

Where did these mobilisations come from? The long erosion of the pro-market consensus that reached its peak in the Reagan-Thatcher years was their period of gestation. This pro-market consensus was never absolute. A substantial section of the working class, often a majority, always rejected it. But a section of the working class, plus a majority of the middle class and the ruling class, made it hegemonic during the boom of the mid and late 1980s. On the international level the economic disaster which accompanied the introduction of Western-style capitalism into eastern Europe and Russia began to undermine this hegemony throughout the 1990s. The East Asian crash of 1997 and the subsequent crisis in Russia reinforced the growing ideological rejection of the market. The 1992 recession also eroded popular support for pro-market policies in the European and American heartland of the system, paving the way for social democratic and Democrat election victories – despite the fact that the social democrats and Democrats continued to pursue neo-liberal economic policies.

As powerful a dissolvent of neo-liberal ideology has been the domestic experience of privatisation. In hundreds of ways the individual lives of millions of people began to get worse because of the practical effects of neo-liberal economic policies. Work became harder, longer and less secure. The provision of health and education became visibly worse and, at the same time, equally visibly tied to market-style organisational structures. Transportation deteriorated in the hands of private companies. Public housing declined, private house prices soared and then collapsed, leaving many homeless or in negative equity. Then house prices soared again. Superstores so dominated the landscape, especially in medium-sized towns, that critical observers could be forgiven for thinking that the truck-shop system had found its contemporary form. Certainly credit card debt became the modern form of pawnbroking.

Moreover, the ‘public culture’ of the post-war boom, of Beveridge and the welfare state, however far short of its idealised form the reality may have been, was replaced with something much worse. The old reformist consensus of ‘Butskillism’ did at least admit that if there were something wrong with society it might be the system itself that was at fault. [2] If there was poverty, unemployment or poorly educated children, for instance, then it might be necessary to regulate the market or reform the law in order to address the problem. But the neo-liberal doctrine assumes that the market is a more or less perfect method of distributing goods and services. Any attempt to ‘interfere’ with the market must end in a less efficient system. Any ‘reform’ must be aimed at allowing the market greater freedom of operation. This is the rock on which the modern social democratic critique of both Stalinism and of ‘old Labour’ ideology stands, just as it was the rock on which Thatcher’s critique of the ‘wet’ one-nation Tories in her own party stood.

Consequently, for Tony Blair as much as for Margaret Thatcher, if there is poverty, unemployment or educational failure it cannot be the fault of the market. Indeed, failures like these can only have two sources. The first source is that the market is not yet free enough. If privatisation does not work, then more privatisation, more competition, must be the answer. The second source of failure is the individual. If someone is unemployed, and if the fault cannot lie with the market, then it must lie with the individual unemployed person. They must not have trained themselves ‘to fit the needs of the market’, or they must have become ‘welfare dependent’, or they must, more crudely and more commonly, be ‘a scrounger’. Equally, if our ‘reformed’ schools are failing it must be the fault of the teachers, the parents or the children for not making the system work. They should be ‘Ofsteded’, or closed down, or have more market-derived structures imposed on them, or simply have their schools handed over to private companies. [3]

Whatever the issue, this logic is one that systematically blames the victim for the crime. It promotes a culture of scapegoating. At its extreme this logic ends in demonising beggars or the homeless, asylum seekers or black people in general. But its effects are just as disgusting, if less obvious, among working people as a whole. This neo-liberal ‘market morality’ attempts to convince working people that they should blame one another for the failures of the system. The social services worker is encouraged to blame the unemployed worker, the parent to blame the teacher. And it attempts to convince us that as long as we can buy a little better education, healthcare or transport provision than our neighbour then we are ‘doing alright’ and they are ‘the problem’.

The great virtue of the anti-capitalist movement is that it expresses the pent-up anger that has consumed many working people for the last two decades. It says to them that they and their kind are not to blame. It says, as many had long suspected, that it is not they who are failing the system but the system that is failing them. Moreover, it tells them that here, right in the heart of the system, hundreds of thousands reject the priorities of the system. This is why the word ‘Seattle’ brings smiles to the faces of any trade union, campaign or radical audience.

Seattle and the demonstrations that have followed it were not just another crowd on the streets protesting about one more issue. Seattle was, in aspiration even more than in numbers, a response on an appropriate scale to what the system has been doing to us for 25 years. It is almost as if a movement has arrived that no longer wishes simply to fight pit closure by pit closure, redundancy by redundancy, welfare cut by welfare cut, and has suddenly decided to try and confront the cause as well as the effects of the system. In doing so it has given a tremendous boost, a whole new ideology of resistance, to every battle against job losses or cuts.

In this sense anti-capitalist movements are giving a particular coloration to every other movement of resistance against the system, no matter how partial. Campaigners against tube privatisation in London suddenly see Balfour Beatty, the likely beneficiaries, in the light of the campaign to stop the building of the Ilisu dam in Turkey by the same company. Trade unionists are now being thrust into a politicised world where environmental protesters and socialists are their allies, where the effects of imperialism and global capitalism on the Third World are being raised point blank, and where mass action is increasingly being seen as the accepted method of struggle.

This raises another qualitatively distinct aspect of the anti-capitalist mobilisations: labour movement involvement. In Seattle, in Millau and in Nice the labour movement participated on a massive scale. Many tens of thousands of organised workers marched in the most politicised environment of the last 20 years. This is a large claim, but it can be justified by comparing the current struggles to earlier movements. The miners’ demonstrations in Britain, especially in 1992, were bigger. But they were defeated and, however angry, were concerned with the single issue. The poll tax demonstration in 1990 was large, militant and victorious but contained no sizeable contingent of organised workers and was concerned with a single issue. The demonstrations and public sector general strikes in France in 1995 are the most obvious precursor. They were part of a rising tide of industrial struggle and highly politicised. But even they did not openly direct their anger against the capitalist system, and they were not part of an international movement in the way that the demonstrations of 2000 have been.

Of course there are real weaknesses with the anti-capitalist movement. It is a movement of a minority. The re-politicisation of even the core of the organised working class is still only at an embryonic stage. It is a movement that is clear what it is against, but less clear about why and what the alternative might be. Many in the movement are not clear about whether or how the organised working class fits in with their opposition to capitalism, despite the labour movement participation in the larger demonstrations.

Even as the demonstrations continue, the ruling class is shifting its positions to try and meet the challenge that these mobilisations represent. The use of the stick continues – the riot police, teargas, armoured cars and border blockades meet every protest. But in Prague and Nice in 2000, and in Davos in 2001 the leaders of the international capitalist institutions, aware of their isolation and unpopularity, have tried to engage in ‘dialogue’ so that they can ‘put the case for globalisation and free trade’. So it came to be that as the World Economic Forum elite met in Davos in January 2001, protected by the police and army inside a 30-kilometre exclusion zone, they offered to debate via a television link with delegates at the anti-capitalist ‘alternative Davos’ conference organised by the World Social Forum in the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre. Multi-millionaire speculator George Soros and former European commissioner for trade Pascal Lamy argued the case with Porto Alegre delegates José Bové and the leaders of Brazil’s Workers’ Party. [4] Different strategies are beginning to emerge within the movement in response to the challenge of incorporation. No doubt the two French junior government ministers and the former French cabinet minister who were delegates at Porto Alegre will favour ‘dialogue’ with George Soros. The majority of activists will see their job as building a mass movement of sufficient power to force the system onto the defensive. A debate is about to ensue.

The revolutionary left has a vital role to play in this discussion, so long as it does not ignore the movement or hector activists in a know-it-all tone. But first the organised left must analyse the new movements and examine how they can be deepened to involve more organised workers and how a strategy to confront the system can be developed. This article is a contribution to that discussion. One crucial issue confronting the new militants is how they should relate to the existing institutions of the labour movement, the Labour parties and the trade unions.

The modern social democratic parties are almost universally proponents of the neo-liberal economic orthodoxy. Their leaders are ‘pro-market’ and ‘business friendly’ to a degree that surprises even the most hardened right wing social democrats of the Cold War era. Consequently, there currently exists an enormous gap between the consciousness of most reformist workers and the policies of the social democratic leaders.

The onset of a period of relative economic stagnation and slow growth in the mid-1970s, followed by the Reagan-Thatcher ‘revolution’, pushed the entire establishment political spectrum to the right. Neo-liberal free market ideology became dominant, socialist ideas became marginalised. But once the boom of the mid to late 1980s collapsed, this right wing tide receded among those sections of the working class where it had taken hold. As it did so it revealed that the old Labour welfare consensus was largely intact, even if the unions and the Labour Party were now much less willing to defend it. The collapse of the Stalinist states, because they were widely associated with socialism, confirmed the prejudices of ruling class and social democratic commentators. It also demoralised the Stalinist-oriented left, which included many on the Labour left. But at just the same time revulsion at the ‘excesses’ of the 1980s was spilling over into a wholesale popular rejection of privatisation, and attacks on the welfare state in general and the NHS in particular.

The 1990s marked a general move to the left in popular consciousness, and therefore exposed the gap between the New Labour type of social democratic leader and the mass of their traditional supporters. This chasm exists over a number of central issues. The neo-liberal social democrats see the central role of the state as facilitating private capitalist corporations to compete more effectively in the market. Most Labour supporters see the role of the state as limiting the damage done to society by the unbridled pursuit of profit. The new social democrat leaders defend the pursuit of profit, the payment of huge salaries and bonuses, the appointment of corporate executives to positions in the state and the welfare state. Most workers oppose such moves. The New Labour ideologues are privatisers down to their bones. Most of the people who vote for them oppose it with increasing bitterness. The New Labour politicians think the welfare state is wasteful and needs cutting back. Most workers think it is underfunded. The neo-liberals are anti-union but most workers are not.

The passage of time since Labour’s 1997 election landslide has done nothing to diminish this gap between the government and its supporters. The government’s own survey, in a chapter titled The working class and New Labour: a parting of the ways?, has examined this divide. It shows that 83 percent of working class people think that ‘the gap between high and low incomes is too large’. Some 57 percent of workers think the ‘government should spend more on health, education and social benefits’. Some 40 percent of workers agree, with only 29 percent disagreeing – ‘even if it leads to higher taxes’. [5] Indeed, the main development noted is that the opinions of many middle class people now shadow the attitudes of workers on these issues. Years of privatisation and cuts are now driving sections of the middle class to draw the same conclusions that working class people reached long ago.

There have also been contrary indications that this disillusionment with the establishment political system could produce the threat of right wing reactions. The election of British National Party member Derek Beackon in London’s East End in 1993 was one such moment. The recent attacks on asylum seekers by the Labour government was another. In Europe the threat has been more substantial: the rise of Le Pen in France, Berlusconi in Italy, the Vlaams Blok in Belgium, the neo-Nazis in Germany and Haider in Austria underline the dangers. But in Britain, and to an even greater extent in France, it has been the left wing trajectory of popular consciousness that has been the dominant feature. This can change, of course. And part of maintaining this left trajectory is to vigorously meet and defeat such right wing threats as soon as they emerge. So far this has been the pattern.

A related fact is that on some social questions – ‘family’ issues, immigration, race, law and order – Labour leaders stand closer to the consciousness of the mass of workers. The British Social Attitudes survey argues, ‘There are in fact two types of class-related issues, and thus two potential sources of divergence between the working class and New Labour: traditional economic issues to do with redistribution, on which the working class are on “the left”, and social issues to do with tolerance, morality, traditionalism, prejudice and nationalism, on which the working class are on “the right”.’ [6] And at times various politicians, both Tory and Labour, have attempted to mobilise popular opinion on these issues to re-establish their support. Sometimes they have been at least partially successful. The initial stage of the Child Support Agency or Section 28, or the first phase of the recent scare over asylum seekers are examples. But resistance from the left, plus the obvious injustice of the measures themselves as they are put into practice, have often turned the ideological tables on the government and its supporters.

More fundamentally, the working class consensus over issues which are essential to the success of any social democratic government – the welfare state most obviously – has remained resolutely opposed to the neo-liberal agenda. And this is what has prevented any further closing of the gap between the policies of the social democrats and the consciousness of most workers.

This does not mean that most workers have a socialist consciousness, let alone a revolutionary consciousness. Nor does it mean they will desert Labour at the ballot box, especially when the Tories are the only viable national alternative capable of forming a government. In many ways working class reformist consciousness has remained remarkably consistent since the 1970s. But mainstream reformism can no longer deliver these aspirations. As a result ‘reformist’ consciousness now finds itself confronted with a crisis of political representation. No establishment politician will put forward a programme that represents these traditional working class needs. In a way this was always true. Labour always only partially represented these aspirations and was even more partial in realising them once in office. But there was some congruence. Now that area of congruity has been reduced to a bare minimum. Support for Labour now devolves more fully than ever to fear of the Tory alternative and less than ever on positive affirmation of Labour policies. Workers vote against the Tories, not for Labour. Or they simply don’t vote at all.

The by-elections and council elections during this Labour government have seen some of the lowest turnouts since the war. Hillary Benn won his Leeds seat in a by-election with just 19 percent bothering to vote. An ICM/Guardian poll shows only 60 percent intend to vote in the next general election compared to 64 percent at the same stage in 1997. The eventual turnout will probably be about 67 percent to 69 percent – the lowest level since 1945. Labour voters are less likely to turn out than Tories, and the lowest turnout of all is expected in the Labour heartland seats. [7]

So many workers vote Labour with a heavy heart, and many don’t vote at all. In both groups there are great numbers who have begun to question the democratic system. In a recent survey 58 percent thought that ‘government ministers putting interests of business before people’ was ‘a major problem’. Another 29 percent thought it ‘a minor problem’ but only 6 percent thought it ‘not a problem’. Financial sleaze in government is a major problem for 49 percent and a minor problem for another 39 percent. Again, only 6 percent think it is not a problem. But perhaps the most damning findings are the ones that show the lack of faith in the parliamentary system as a whole. Two years ago only 41 percent of people though the system of governing was working well. Today that proportion has fallen to 31 percent. [8] Further evidence of this mood is contained in table 1.

|

Table 1: LOSING FAITH IN DEMOCRACY |

|---|

|

Do you think this country is getting more or less democratic? |

|

|

Do you trust ministers and their advisory committees to tell the truth about each of the following? |

|

This process is also reflected in the erosion of Labour’s core organisation. Labour’s membership has fallen during the course of its time in government. Fewer now attend ward or constituency meetings. Fewer canvass at election times. Councillors regularly defect not to the Liberals or the Tories, but to become Labour independents. A minority have begun to search for a new political home. As they do so, even though they start out from traditional reformist consciousness, the fact that the traditional organisational receptacle for this consciousness is no longer adequate forces them to begin to draw more left wing conclusions. They reconsider whether the old party was ever socialist. And if it was not, they ask themselves, why not? They consider allies to their left that they had previously rejected. And they re-evaluate other methods of struggle, from trade unionism and environmentalism, through direct action, to revolutionary organisation, which had previously not interested them.

This is why the rise of the anti-capitalist movement is of such central importance to the crisis of reformism. It provides an alternative ideology and an alternative political home for reformist activists. This home too may only be temporary, but it is at least a house where those breaking from reformism to the left and revolutionaries can co-operate to build a stronger movement. Here too they can debate the way forward. The same general point can be made about the Socialist Alliances that have tried to provide an electoral alternative to the left of New Labour.

This process of recomposition is more advanced than many on the left realise, but it still affects a minority in the labour movement. Many trade union leaders have accepted a version of the neo-liberal consensus only a couple of steps to the left of the Labour Party leaders themselves, though the evident contempt with which New Labour treats the unions has ruffled the feathers of even these chickens. But below the level of the union leaders, the fundamental strength of the unions and the strength of their ties with the Labour Party remain considerable. Talk of ‘Tory Blair’ indicates the depth of disillusionment with the New Labour project. It would be foolish of socialists not to share and express this bitterness. But error creeps in at the point where this rhetoric crosses over into a serious contention that the Labour Party has fundamentally changed its nature.

The arguments to support the contention that the Labour Party has become a second Tory party are as follows: (1) the leader, Tony Blair, is the most right wing the Labour Party has ever had; (2) the policies of New Labour are more right wing than ever before; and (3) Labour is now funded by big business and not by the unions. Let us examine these arguments in sequence. Tony Blair is certainly a right wing, pro-market politician. And Blair’s values are so at variance with those of most Labour Party members that it can easily be true that, as Peter Mandelson’s friend the author Robert Harris puts it, ‘Blair hates the Labour Party.’ But he has yet to split his party, as did a previous generation of Labour leaders – Roy Jenkins, Shirley Williams, William Rodgers and David Owen – when they formed the Social Democrats. Nor has he split his party and joined a Tory government, as Ramsay MacDonald did in the 1930s. It seems premature, therefore, to conclude that Blair is more right wing than all his political ancestors.

Neither are the policies of the Labour government more right wing than those of Jim Callaghan’s government in the 1970s. That Labour government still holds the distinction of being the only government in post-war British history which, through the Social Contract, forced down the real wages of employed workers. Its policy on immigration, including the introduction of virginity tests, was a match for New Labour’s, and it led directly to the rise of the National Front. Callaghan’s infamous ‘family values’ speech was the template around which all subsequent reactionary Tory and Labour social commentaries drew. And Denis Healey, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, introduced the IMF cuts package which set the tone for the whole Thatcher period, just as Labour’s strike-breaking during the Winter of Discontent paved the way for Thatcher’s anti-union drive. It is true, however, that Tony Blair has abandoned the ‘old Labour’ welfare state consensus. To find a full parallel for this kind of devotion to free market economics we would have to go back to pre-war leaders of the Labour Party like Ramsey MacDonald and Philip Snowden.

Finally, it is not true that union money is now irrelevant to the Labour Party. The £8 million which Labour fundraisers want from the unions for the party’s election fund is decisive in allowing the party to compete effectively with the Tories. It is true that there are more individual and business donations to the Labour Party than previously. It is also the case that some of these come from business people disaffected with the Tories at a time when that party is at a historic low in its electoral fortunes. It is certainly true that this development has encouraged New Labour’s pro-business stance, and that it has increased the level of sleaze in the Labour Party. But this is not the same thing as saying that the Labour Party has fundamentally changed it character. It is still the political expression of the trade union bureaucracy and it enjoys the support of most organised workers. It is, as Lenin described it, a ‘capitalist workers’ party’. That is, it is funded and supported by organised workers despite the fact that it supports the capitalist system.

The challenge for socialists is to act on this contradiction in a way that appeals to the class consciousness which encourages workers to support Labour rather than the Tories in order to detach them from their allegiance to the Labour Party. Asserting that they and their party are the same as the party of William Hague, Michael Portillo and Ann Widdecombe is not the best way to do this. It is far better to explain that, while we will always support the party of the trade unions against the open and unashamed party of the bosses, we want to build a real socialist alternative to both. Many workers already detest the Blair government for continuing Tory policies. They are right to do so. We share their anger. We and they can win many more workers to a socialist alternative. This is best done by showing that there is a better and more consistent way of fighting for the very things Labour supporters thought they would achieve by backing the Labour Party in the first place. Our approach in the coming election should be ‘vote Socialist where you can, vote Labour where you must’.

Reformism will not crumble simply as a result of its current crisis. To understand why, we have to look at the fundamental reasons workers hold reformist ideas in the first place. This in turn requires us to pay some attention to the social position that workers occupy in capitalist society. This position is a contradictory one. On the one hand the collective labour of workers is the basis of production in society. At the birth of capitalism the steam engine could not function, nor the power loom weave, nor ships put to sea without the labour of workers. So today power stations do not function, nor cars and planes get built, nor supermarkets open without the labour of workers. This invests workers with a tremendous potential power to determine the fate of society.

On the other hand, workers today can no more gain access to the means of production than they could at the birth of capitalism. Just as the textile mills, the factories, the department stores of the past would only allow a worker access to the means of production if they agreed to the condition of wage labour, so it is in the car plants, the call centres, the supermarkets of today. As it was then, it is now: the hours, the type and conditions of work along with the rate of pay are still largely determined by employers. Having to sell their ability to work to employers encourages workers to believe that they are powerless in the face of the vagaries of the ‘labour market’, depriving them of the sense that they can shape their own destiny.

This is the root of contradictory consciousness among the working class. They are the wealth creators, potentially the most powerful class in capitalist society, the class on whose action, both economic and political, the fate of the society turns. But they are at the same time reminded on an hourly basis that they only work when the forces of the market permit, that their fate rests with this impersonal power, that they are subordinated by the very wealth they create.

The initial form in which this situation is reflected in the minds of workers is a consciousness that tries to bind together these contradictory impulses – on the one hand the impulse to transform capitalist society, on the other the feeling that such transformation must not exceed the limits stipulated by the ruling class. Reformism is one of the most characteristic forms that this consciousness takes. Reformism codifies and crystallises the notion that, although the society requires alteration, such transformation can only take place within the economic and political institutions provided by the system itself. Trade unionism, the desire to better the terms on which workers are exploited, is one expression of this process. But trade unionism, operating primarily at an economic level, raises the question of what sort of political organisation workers should build. Reformist political parties are only one possible alternative, though to many workers they initially seem the most plausible.

It is for this reason that reformist consciousness, sometimes of a more left wing variety and sometimes of a more right wing variety, dominates the thinking of the majority of the working class for long periods of time. Consequently, both revolutionary ideas and outright reactionary or conservative ideas are for equally long periods minority currents within the working class.

There is, however, a problem with this account of reformist consciousness. On this analysis we would be driven to the conclusion that reformism is the ‘natural’ home of the majority of workers. Yet we know that this is certainly not the historical experience. In decisive moments of historical change the majority of workers come to embrace the belief that they can transform the existing society by the direct use of their own power institutionalised in bodies of their own creation. Such was the situation in Russia in 1917, in Germany between 1918 and 1923, in Spain in 1936, in Hungary in 1956 and in Poland in 1980–1981, for instance. Such upheavals, along with many more minor crises that have disrupted the existence of a reformist compromise in workers’ ideology, grow out of the fundamental economic instability of the system. The assumption that we can get some of what we need by working inside the system is challenged by periods where capitalism fails to meet the economic, social and political aspirations of working class people. At such times the growth of a revolutionary minority into a majority becomes possible. That this revolutionary consciousness is not always fully formed, institutionally expressed and therefore ultimately successful in every previous revolution is exactly the issue it is now necessary to address.

Capitalism is so economically, socially and politically unstable that it periodically undermines the class compromise that underpins working class reformist consciousness. The Labour Party is currently caught in the coils of one such crisis. The capitalist system has been increasingly trying to shift the burden of the crisis onto the shoulders of working people for more than a quarter of a century. Economic growth is not only much slower than during the post-war boom, but lower in the 1990s than in the 1980s. As the Financial Times reports, ‘Remember that economic growth between successive cyclical peaks was 3.3 percent a year in the 1980s, against about 3.1 percent in the 1990s.’ [9]

Labour is grappling with the effects of this long cycle of attacks on workers. Its quick fixes fail, and the system does not have the resources for a work of more substantial reconstruction in key areas such as public transport, health and education. This leaves many Labour supporters in as dire straits as they were under Tory rule. Indeed, some are worse off. Between 1995–1996 and 1997–1998 the number of people on very low incomes (less than two fifths of the national average) grew by more than 1 million to a total of 8 million. In 1998 14 million people were below the government’s poverty line. This included some 4.4 million children compared with an estimated 1.7 million in 1979. The level of unemployment significantly affects poverty. And although Labour boasts that the official figure for unemployment is at a 25-year low, calculated by those claiming benefits, the real number of those who would like paid work but have none now stands at 4 million. [10]

Even the great good fortune of Labour’s first term coinciding with the upswing of the business cycle and buoyant government finances has not allowed Blair and his ministers to effectively deal with these structural issues. As Peter Kenway, co-director of the New Policy Institute, argues:

Time will tell if the measures announced in recent budgets can succeed in turning the tide of poverty and social exclusion. But these figures show that an improving economy and falling unemployment are not enough on their own. As the government’s policies for tackling these problems begin to bite, poverty is at levels close to the high-water mark reached in the early 1990s. [11]

Such a high-water mark was reached in the early 1990s not only because of the effects of long years of Tory government but also because the early 1990s were a time of serious recession. Labour has so far avoided having to govern through such a period, mainly because of the reflationary measures taken in the US to avoid the 1997 crash in South East Asia and Russia spreading to the Western industrialised countries. But Labour will not be able to avoid this conjuncture forever. Any recession will not only worsen the material conditions in which Labour voters live, it will also do great damage to some of the most cherished myths in the New Labour ideological lexicon.

One such myth was that the boom was the result of a ‘new economy’. New Labour bought the ‘new economy’ theory wholesale from American economic pundits and Clinton spin doctors. The belief was that the business cycle was at an end, and that new flexible markets and new technology firms would ensure it never returned. Gordon Brown seemed at times to be repeating word for word the speeches of Nigel Lawson in the late 1980s – just ahead of one of the severest recessions of the post-war period. Now, once again, previous cheerleaders for the new economy theory are voicing their doubts. The Financial Times argues:

The business cycle is decidedly alive. That should not surprise anybody...cycles can occur – and frequently have occurred – in flexible economies with credible monetary anchors. All that is needed is a big investment expansion fuelled by expanding credit and a strong stock market. Indeed, the firmer the belief that the business cycle is dead, the greater the confidence and the likelihood of business cycles. [12]

Neither has the Financial Times now got much time for that other economic icon of New Labour, the reviving powers of the dot.com revolution:

Internet mania looks like an only slightly less irrational version of the South Sea Bubble. The notion that information technology represents the greatest transformation since the industrial revolution is historically illiterate. The technological changes between 1880 and 1940 exceed, in both scope and intensity, all that has happened since.

Those changes included new sources of energy (electricity and petroleum), new industries (motor vehicles and pharmaceuticals) and new products (cars, washing machines, telephones, radio, television, penicillin). They profoundly altered what was produced and how. They also transformed the way people lived. Against all that, what are the personal computer and even the internet? [13]

The economic prospects for Labour’s second term do not look promising. The social, political and ideological impact of another recession is likely to deepen the crisis of reformism.

This crisis raises the question of what organisations and institutions inside the working class can accelerate or retard the development of a socialist alternative to New Labour. This is a vital question because no economic or social crisis is ever sufficient in itself to ensure the replacement of reformist consciousness with revolutionary consciousness. Reformist consciousness is always embodied in certain theories, ideologies, institutions and organisations. And so too must its revolutionary replacement. Ideologies and theories are always concretised and popularised by organisational forms. Some group must organise to disseminate by whatever means – speaking, broadcasting, e-mailing, phoning, printing and distributing – a common set of ideas. Effective action that corresponds to these ideas must be organised by co-ordinated networks of politically informed activists. In short, such action requires political organisation.

Reformism is weak when it is unorganised by trade union leaders and social democratic parties. Paradoxically, the underdeveloped level of reformist organisation, a product of Tsarist repression, ultimately undermined Tsarism in Russia in 1917. Nevertheless, reformist organisation can grow rapidly, even in a revolutionary situation, by battening onto workers’ desire to transform the system without confrontation, as did the Spanish and Portuguese social democrats after the fall of the fascist dictatorships in the 1970s. But so too can revolutionary organisations, especially in such times of flux, if they know how to exploit the cracks appearing in the reformist consciousness and reformist organisation.

One such prolonged period of transition appears to be under way in Britain today. The end of the post-war boom in the 1970s and the decades of slow economic growth that followed have restricted the reformists’ ability to grant meaningful reforms. The welfare state consensus and the toleration of some trade union influence on government are now greatly curtailed. Active participation in Labour Party organisation is at an all-time low. As a consequence popular scepticism about the political system as a whole is at historically high levels. The links between trade union activists and local campaigners on the one hand and Labourism on the other is weaker than at any point in the post-war period.

But for all this Labourism is far from dead. The 8 million workers in the unions can still be addressed and influenced by union leaders deeply committed to the reformist project. The repellent power of the Tories, despite the current weakness of the Tory party, is still a powerful call on the loyalty of class conscious workers. What is necessary to turn the crisis of Labourism into a step forward for the working class is to actively replace reformist organisation with an alternative. Reformism never simply disappears. It always has to be actively replaced by a superior set of ideas embodied in an alternative organisation. Reformist workers have to be sure that the things they thought could be fought for by joining the Labour Party can be better achieved by other methods before they will desert the Labour Party, even a Labour Party whose leaders have turned their backs on these workers’ most cherished aspirations.

This will not happen all at once. The erosion of reformism will be a long process. As workers reject their old leaders they will not immediately flock to revolutionary organisation. They may believe that ‘old Labour’, even in its more right wing forms, is what we need to recreate. Many will certainly believe that the ideas of Bennism at its high point in the early 1980s provide a model for reviving the Labour movement. Some will despair of parliamentary politics and believe that single issue activism is now all that can be done. Others will want to combine this with participation in the anti-capitalist movement, believing that movements rather than parties are now the best option for radicals. The 15 or 20 years of internal war by the right wing against the left wing in the Labour Party, from the defeat of Bennism, through the expulsion of Militant, to the resignation of Ken Livingstone, has produced a generation of exiled activists. The rise of Tony Blair has massively added to their number. The revival of the wider movement, crucially around anti-capitalism broadly conceived, has thrown them together with revolutionary socialists in common struggle. The issue that now confronts us is how to build the most effective socialist movement in these new circumstances.

To understand how to build the anti-capitalist, labour and socialist movement we need to clearly state its current composition. Its dominant element is the anti-capitalist element, but not because anti-capitalist activists are the most numerous part of the movement, certainly in Britain. The anti-capitalist element dominates because it gives a shape, a wider ideology to a host of other struggles. The anti-capitalist activists, among them revolutionary socialists, may be a minority of the movement, but their arguments find a profound echo among much wider layers of workers. These people, once they are in touch with such ideas, sometimes through direct contact with activists, sometimes simply through reading the books and journalism of anti-capitalist writers, become more consciously anti-capitalist themselves.

Single issue campaigners are, in formal terms, probably still the most numerous element of the new movement. The range of issues around which people are organising is almost dazzling in its diversity. There are international campaigns on issues of such general importance to the system that it makes little sense to simply refer to them as single issue campaigns. Drop the debt campaigners in Jubilee 2000, environmental campaigners in People and Planet or those campaigning against sweated labour in the Third World are confronting a ‘single issue’ of such enormity that its political ramifications demand a more general critique of the system. Many of these activists have such a critique, although it may not be a revolutionary or socialist critique. Nevertheless, it is not easily absorbed within the usual bounds of reformist politics either.

Then there are campaigns around national issues such as privatisation of public transport and the NHS, in opposition to neo-liberal education policies, the sell-off of council housing, and so on. These campaigns are also the most likely nexus where trade union action and general campaigning meet. The anti-capitalist movement lends a general critique of the system to these struggles in a way that was not available in the past even to much more numerous and militant campaigns, such as the anti poll tax movement. Not all the 75 percent of the population who were opposed to privatisation of the rail network would consider themselves anti-capitalist, but a significant minority are now open to a thorough-going critique of the market.

Beyond this there are a mass of local campaigns to save schools and hospitals, to stop landfill sites and incinerators, against runway developments at local airports, or the closure of swimming pools and libraries. These too have a political significance beyond their immediate goals, because the environment in which they now take place gives them a general political charge that they previously lacked. Now people say, however small our struggle, we are all against the privatisers and their corporations, against the fat cats in industry and government, against the spin doctors and their political masters, local and national.

Yet more people are beginning to enter this movement from trade union struggles. Trade union militants were hit hardest by the defeats of the Thatcher years. The recovery has been long and is by no means complete. But a radicalised consciousness already exists, as ballot after ballot in favour of strike action proves. And increasingly action is beginning to result. In the Post Office and, to a lesser extent, in the car industry in particular the tide of struggle continues to surge forward, only to fall back when it encounters the barrier of the trade union bureaucracy. But the rise in the general level of the movement, and the government’s hostility even to the trade union bureaucracy, is beginning to make it seem much more likely that one or another of these forward surges will begin to finally turn the tide on this front.

There have also been some important changes on the electoral front. Political discontent with New Labour has recently found expression in this least promising of all territory for socialists. Ken Livingstone’s decision to split from the Labour Party and run his own campaign for London mayor broke the mould. Livingstone’s actual campaign was both low key and by no means socialist. But the fact that someone still widely known as Red Ken, with a left wing past, could break from Labour and beat the Millbank machine in a highly publicised electoral battle was more significant than Livingstone’s middle of the road policies. Labour activists in London simply refused to fight for their candidate. Many of them supported Livingstone either openly or covertly, and some also supported the London Socialist Alliance candidates for the Greater London Assembly.

In many localities independent, socialist or local campaign candidates have taken on Labour and beaten it. This is most obviously true of the Scottish Socialist Party’s electoral success. But it is also true in Preston, Coventry, Burnley, Kidderminster and other places. These developments have coincided with a widespread questioning by trade unionists of political fund donations to the Labour Party. The postal union, the CWU, is due to debate this issue, and it has been a constant argument in the Fire Brigades Union. The election of Mark Serwotka in the PCS, the civil servants’ union, means that support for the Socialist Alliance will be raised here as well. In every union activists who raise this issue can be sure of the most sympathetic hearing they have received in decades.

This then is the composite nature of the audience for socialism. Some of these people are directly and immediately open to the ideas of revolutionary socialism. But many are not. They are not hostile to revolutionary politics, except in a small minority of cases. They want to work with revolutionaries in a common project of rebuilding the left, and are willing to discuss our ideas and theirs in the process. The crucial question, therefore, is what structures we can build together which allow us to rebuild the movement and continue this debate. The unions are clearly one vital forum, bequeathed to us by the history of the working class. But there are other, new organisations that we need to build afresh. The united front is clearly one formula on which we can draw in the arena of general campaigning. The electoral field provides fewer models from the past of the socialist movement, although there is some experience on which we can draw. Let us look at each of these in turn.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s the long post-war cycle of economic expansion began to falter and the first major crisis shook the Western economies. The stable conditions and full employment of the boom had allowed trade unions in Britain to expand their numbers, taking in many white collar workers as well as the traditional core of manufacturing workers. It had also allowed shop stewards’ organisation to take root in many workplaces. The shop stewards drew their strength from their ability, in a tight labour market, to determine working conditions and wage levels by the use or threat of strike action. Such strikes were often brief and limited in their demands. As such they did not need to appeal to the trade union bureaucracy for assistance and so were often unofficial.

When the economy began to falter this type of trade union organisation was identified by employers and government alike as the cause of the ‘British disease’. The Wilson government of the late 1960s first mooted legislation to curtail union power in the white paper In Place of Strife. A union revolt put paid to this project in the short term. But it was the parent of all the attempts to shackle the unions that followed. There were many children. Ted Heath’s Tory government’s Industrial Relations Act was one.

The combination of an economic crisis and a government and employer anti-union offensive clashed with the shop stewards’ organisation and the left which had grown out of the 1960s. The result was, at first, a stunning victory for the working class against the Tory government. The strikes of 1972 destroyed Heath’s industrial relations legislation and the miners’ strike of 1974 destroyed the government. But the coming to power of a Labour government exposed the fatal weakness of the working class movement – its political leadership. The shop stewards’ organisation was dominated by the political influence of the Labour Party itself and the Communist Party. The policy of both was to support the ‘social contract’ between the unions and the government. The effect was to politically behead the shop stewards’ movement. Real wages fell as the union leaders and the increasingly bureaucratised convenors and senior stewards policed the rank and file for the Labour government. Despite the late revolt of the Winter of Discontent the failure to provide an alternative political leadership inside the working class movement led to Thatcher’s election victory in 1979.

The 1980s were marked by a series of intense class battles. The steel workers’ strike of 1981, the miners’ strike of 1984–1985, the printers’ strikes in Warrington and Wapping, and the dockers’ and seafarers’ strikes were long, hard fought, defensive strikes characterised by a low level of rank and file initiative. Every one was defeated. It was one of the most sustained series of reverses for any working class movement in the industrialised world. The ruling class gained some of the most draconian anti-union legislation of any industrialised country. The union leaders buckled.

Despite this shocking series of defeats the British trade union movement remained remarkably resilient, even though its activists were deeply unconfident. At its height there were 12 million workers in the unions. The number is now 8 million. But the decline was mostly a result of high unemployment, peaking at over 3 million during the 1980s, and the changing structure of industry. The government’s own Social Trends survey reports that since its peak in 1979 ‘the largest fall in union membership occurred in 1992, a period of substantial job losses, and the unions have failed to recover membership loss as employment growth has recovered’. [14] This meant that people lost union jobs and, when they were re-employed, there was either a weaker union they did not join, or no union at all.

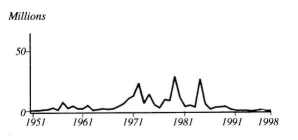

|

Graph 1: UK LABOUR DISPUTES – WORKING DAYS LOST |

|---|

|

There is no evidence, however, that people left the unions because they were ideologically opposed to them as was often claimed in the Reagan-Thatcher years. In the US, where only 13 percent of the population are in unions, a full 65 percent approve of unions and 32 percent of workers say they want to join a union. [15] Opinion poll evidence in Britain also shows a high level of support for unions. This underlying fact has now registered in increasing union numbers in the last year. Union recognition has also increased substantially, partly as a result of Labour’s union recognition legislation. In 2000 there were 159 union recognition deals struck, twice as many as in 1999. These deals were mainly in private firms, where the union movement was most weakened in the 1980s.

What is happening here is quite clear. The generalised anti-capitalist mood, though still in its fully fledged form the property of a minority, is pulling up the mood of resistance in much wider layers of the class. This in turn is beginning to erode the mood of defeat in the unions, thus affecting their numbers and willingness to take action. This process was already observable in small ways during the 1990s, in the signal workers’ dispute of the early 1990s or the British Airways dispute in the first months of the Labour government, but it has become more pronounced in the last year. The 100,000-strong Rover demonstration, the ferment in Ford Dagenham and at Vauxhall in Luton, the repeated action in the Post Office and by the rail unions have all looked at one time or another as if they would spill over into a decisive struggle on the industrial front. So far the mood has rolled forward and then been rolled back by the union bureaucracy. But the expectation must now be that this process will create an industrial focus for the political discontent that is already the hallmark of the period.

However this may be, what is certain is that there already exists an increasingly politicised minority in every union that is beginning to see the opportunities to rebuild militant trade unionism. This is why it has been possible, despite the absence of a high level of industrial action that has been the usual precondition of such initiatives, to launch successful rank and file papers in the car industry and the Post Office.

The task of socialists is to increase the organisation and independence of action of the rank and file in relation to the employers. Such a task requires independence of action and organisation in relation to the trade union bureaucracy. And this requires a political independence from the Labour Party loyalties of the trade union leaders. It is for this reason that effective rank and file leadership cannot be created without the participation of revolutionary socialists. The critical weakness of the organisationally powerful shop stewards’ movement of the 1970s was its ideological dependence on the Communist Party. The strength of the new rank and file movement must be that socialists stand at its core. Some of these socialists will be revolutionaries, but those who are not must be won to the idea that independence of action, which means political independence from Labour and the Labour-supporting trade union leaders, is the keystone of any effective rank and file movement.

Thousands of new activists are moving into political activity. The issues on which they are doing so range from school privatisation to global warming, from the erection of telephone masts to the use of child labour in Third World countries, and from council housing sell-offs to genetically modified crop trials.

The majority of these activists are clearly not revolutionary socialists and would perhaps not even describe themselves as socialists of any variety. But neither are they convinced reformists in the sense that they are members of, or deeply committed to the values of, the Labour Party. They may be Labour voters, but they are likely to be so more out of a hatred of the Tory party than an ideological fervour for New Labour. They are likely to share many of the sentiments of more openly committed anti-capitalist activists, including a commitment to active campaigning, but they will not necessarily see the working class as the key agent of social change. Commitment to grassroots activism will go hand in hand with admiration for left wing Labour MPs like Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn, and journalist-activists like George Monbiot, Susan George, John Pilger, Naomi Klein, Mark Thomas and Paul Foot.

One central task for revolutionaries at the moment is to engage in joint work with these activists in order to rebuild the left. In each campaign the notion of the united front is essential if this task is to be accomplished successfully. The notion of the united front is as old as the working class movement. Its first national formulation was Chartism. Its basic premise is that whatever political differences there may be among different layers and currents in the working class movement, it is still essential to unite in action around common working class goals if we are to be effective against the ruling class. The basic principle of trade unionism – united we stand, divided we fall – is at heart the same as the basic principle of the united front. A trade union deliberately and rightly seeks to unite workers around fundamental issues of wages and conditions irrespective of their political allegiance be they revolutionary, Labour or even Tory. The united front differs in the sense that the point of unity is often a political demand – in defence of council housing or against immigration controls – but the principle remains the same. No worker or working class organisation that agrees with the purpose of the united front should be excluded.

That those bodies included in the united front are composed of workers, or at least not inimical to the interests of workers, is important. It should not be a condition of participation in a united front that everyone agrees on wider socialist values. But it would clearly not advance either the general struggle or the fight on the particular issue if, for instance, the Nazi British National Party, who were opposed to the poll tax, were welcomed into the anti poll tax campaign. Nor would it advance the struggle against the anti-union laws to include in it various right wing Tory ideologues who oppose the legislation because they are opposed to all ‘big government’ interference with the labour market. Various individuals from other classes may identify with the aims of the campaign – but that should be because they have deserted their traditional political stance to do so, and not because the campaign has weakened its standpoint in order to accommodate them.

A second and perhaps larger danger is that the united front becomes simply a talking shop. Of course any campaign needs discussion about its aims and methods. But the great virtue of uniting around a single issue is that the broad parameters of agreement should be decided by the demands of the campaign itself. After all, you are either for or against rail renationalisation, cuts in the NHS or selling off council houses. The real point of the campaign is to mount effective, united action to achieve its goal. Such action is precisely more effective because it brings together individuals and groups who would otherwise disagree but who find themselves united on the single issue. But such unity is only effective if it results in action. Unity in name only, unity in passivity, achieves precisely the same as disunity – nothing. A united front is only a united front when it acts, otherwise it is merely a discussion circle and, since everyone is united on the issue, not a very interesting discussion circle either.

Leon Trotsky provided a general outline of the united front:

… the Communist Party proves to the masses and their organisations its readiness in action to wage battle in common with them for aims, no matter how modest, so long as they lie on the road of the historical development of the proletariat; the Communist Party in this struggle takes into account the actual condition of the class at each given moment; it turns not only to the masses, but also to those organisations whose leadership is recognised by the masses; it confronts the reformist organisations before the eyes of the masses, with real problems of the class struggle. The policy of the united front hastens the revolutionary development of the class by revealing in the open that the common struggle is undermined not by the disruptive act of the Communist Party but by the conscious sabotage of the leaders of the Social Democracy. [16]

Trotsky was writing about mass Communist parties and mass reformist parties in the 1930s, but the same general approach can be applied by much smaller revolutionary organisations today. Mostly their small size will prevent them reaching agreement with national trade union leaders or the national leaders of reformist organisations. But with some union leaders, certainly with some local leaders and reformist MPs such unity is possible. And understanding that such an approach is desirable will prevent revolutionaries from erecting unnecessary barriers between themselves and rank and file reformist workers.

A second point that Trotsky makes here is also of great contemporary relevance: it is through joint struggle that the differences between revolutionaries and reformists become apparent to reformist workers. It is not, in the first instance, because revolutionaries differentiate themselves or counterpose themselves to the reformists inside the united front that reformist workers are drawn to them. It is rather because revolutionaries show in practice that their methods of struggle are superior, more consistent and effective in achieving the joint aims of the united front that reformist workers become open to more general revolutionary politics.

In any struggle, no matter how limited its goals or how ‘reformist’ its demands, the choice of the methods of struggle will reflect the wider politics of those involved. Reformists, especially reformist leaders, will generally favour more passive methods of struggle, be more concerned not to ‘offend public opinion’, depend more on the bureaucracy of the labour movement and less on its rank and file. They will be the first to want to retreat if the fight begins to have more far-reaching consequences. But many reformist workers will not share this approach. They will want to use the most effective methods – those that rely on mass mobilisation, rank and file action, and so on. This is what revolutionaries desire as a matter of principle. For revolutionaries the basic principle of Marxism, the self activity of the working class, is present in every small struggle just as it is in a revolution. It is this principle which binds them to reformist workers who, simply out of a desire for the most effective methods of struggle, come to the same conclusions.

This process can open up the possibility of winning reformist workers to revolutionary conclusions, but it cannot complete the process. For this, other factors must become operative. One is the impact of the wider world. The struggle itself can, more or less sharply depending on its scale and nature, raise issues far beyond the scope of the united front. The role of the police, the state and the media can all become issues of intense discussion during such struggles. International events, struggles in distant parts of the globe, can suddenly seem relevant to workers engaged in united front activity in a way they did not before. But to draw out the full meaning of such issues an organisation that brings to bear on contemporary struggles the whole experience of the working class movement, historical and theoretical, must be present. This is the crucial interface at which reformist workers can be won to revolutionary socialism.

The nature of any particular united front is of course shaped not just by the balance of forces between revolutionaries and reformists. The wider conditions of the class struggle profoundly affect the kind of united fronts that are possible as well as the demands they raise. In the late 1970s and again in the early 1990s the Anti Nazi League created a very effective united front with some reformist politicians, many activists who were broadly reformist in consciousness and a core of revolutionary socialists. But in both cases the wider balance of class forces did not make political generalisation easy. In the late 1970s the downturn in industrial struggle was under way and in the early 1990s its effects were still being felt. This limited the impact of the ANL on the wider struggle.

Many struggles today are still defensive in nature precisely because the neo-liberal inspired attacks on jobs, conditions, unions and the welfare state continue. However, because the political consciousness of many activists is rising the context of united front activity has changed. This makes it possible to initiate united front activity on a wider scale and with greater possibilities of political generalisation. And years of attacks on socialists within the Labour Party and its adoption of the neo-liberal policy agenda have weakened the purchase of reformist leaders and the strength of reformist ideology, resulting in increasing numbers of ‘old Labour’ and left Labour figures countenancing unity with the far left. The rightward trajectory of their own organisation makes it more difficult for New Labour supporters to win their own rank and file away from the influence of revolutionaries. The disappearance of the Communist Party also undermines the effectiveness of the Labour Party cadre that previously relied on it both for ideological guidance and to discipline the far left.

The institutions of parliamentary democracy are inextricably tied to the bourgeois state machine. They cannot legislate a socialist society into being because the ruling class would not permit it and, as importantly, because the creation of a socialist society requires the active participation of the majority of workers. It thus demands new institutions, democratically elected workers’ councils, which embody this principle. Even when Trotsky was arguing against the ultra-left in the Communist International and in favour of electoral participation he was careful to restate this point of principle:

… parliament has been transformed into a tool of lies, deceit, violence and enervating drivel ... That is why it is the working class’s immediate historic task to wrest this apparatus from the ruling classes, smash and destroy it, and replace it with new organs of proletarian power. [17]

This is the very first letter of the revolutionary alphabet. But it is far from being the whole story of revolutionary strategy and tactics. Indeed, it is not even the whole story about parliamentary democracy.

In the first instance parliamentary democracy is a form of bourgeois state which, under certain circumstances, revolutionaries defend. In the face of a military coup or a fascist rising, for instance, revolutionaries would make common cause with reformists in defending parliamentary democracy even if, in the course of such a struggle, we would seek to increase the strength of the revolutionary forces to the point where parliamentary democracy could be replaced with a superior form of democratic institution. This is what happened in Russia in 1917 when the Kornilov coup against the Kerensky government was defeated by the workers’ councils which then went on in October to replace Kerensky’s government itself.

Secondly, parliamentary elections and the parliaments themselves may not be the decisive site of class struggle, but they are nevertheless a reflection of that struggle. In the debates in the Communist International on the question of electoralism Lenin argued:

It has been claimed here that we waste a great deal of time by participating in the parliamentary struggle. Can one conceive of any other institution that all classes participate in to the degree they do in parliament? This cannot be created artificially. If all classes are drawn into the parliamentary struggle, it is because class interests and class conflicts are reflected in parliament. If it were possible everywhere and immediately to bring about, let us say, a decisive general strike to overthrow capitalism at a single stroke, the revolution would already have happened in a number of countries. But we must reckon with the facts, and parliament is a scene of the class struggle. [18]

Thus participation in parliamentary elections by revolutionaries can be a method of increasing the consciousness and combativity of the working class – exactly the opposite of the effect desired by establishment defenders of the parliamentary system. For as long as workers look to parliamentary democracy to remedy their grievances with the capitalist system revolutionaries will find an audience for their views by standing in elections. The Bolsheviks were still standing in parliamentary elections, to the Constituent Assembly, after the October Revolution. The point of such a revolutionary election campaign is not to deepen the atomisation of workers by running candidates who claim that the parliamentary system can solve workers’ problems as long as voters return revolutionaries rather than their opponents to power. On the contrary, the aim is to give voice to working class demands which are normally excluded from mainstream political debate, to agitate for action from below, to support those workers who are already fighting, to make general socialist propaganda, and to criticise the ruling class and reformist parties.

In the Communist International discussions J.T. Murphy, the veteran of the shop stewards’ movement and early leader of the British Communist Party, made this point:

The problem before us is not one of keeping ourselves spotless before the world but of carrying the revolutionary struggle not just into the institutions of the working class but into the enemy camp as well ... These tactics are thrust upon a fighting movement by the varying situations in which workers find themselves from time to time. It is not always possible to carry out a strike, and no strike movement maintains itself at a constant pitch of enthusiasm. There are times when it is possible to ... make a frontal attack. But there are also times when ... it is necessary to rally every possible source of strength, to retreat, to make flanking attacks, protest here and there, in short to do everything to keep our forces together. It is on such occasions that we recognise the value of agitational forces inside parliament, and it is on such occasions that our movement has been forced to utilise them. [19]

Murphy went on to warn that if revolutionaries do not create their own leaders in the electoral sphere, be they MPs or, more commonly today, merely candidates recognised as local leaders, they are forced to rely on the reformist and establishment parties:

These situations and these experiences force us to realise the many-sided nature of our fight. To throw aside a weapon such as parliamentary representation of Communists and find ourselves in the ignominious position of having to appeal for aid to the Liberals and reformist Labour men would therefore be the height of folly. We must fight as revolutionaries ... who know how to meet the varying needs of the struggle and not be afraid to mix with the enemy when the occasion demands it. [20]

Such electoral campaigns are not always possible. Sometimes the forces of the revolutionary left are too weak to mount a credible campaign. Sometimes the general balance of class forces, or the balance of political forces in the electoral arena, is so unfavourable that even a sizeable revolutionary party cannot intervene successfully in an electoral campaign. In Britain in the 1970s the Socialist Workers Party, among others, stood candidates in elections. The SWP’s results were poor, but the vote obtained by other socialists was not qualitatively better. The fundamental problem was that the downturn in the class struggle had begun, the focus for many on the left was increasingly directed at the left of the Labour Party and, consequently, the space for a revolutionary electoral initiative was closing down.

Today conditions are different. Most importantly there is a popular mood which stands to the left of the leaders of the Labour Party on nearly all the fundamental issues which are the mainstay of reformist politics: unemployment, funding of the welfare state, pensions, transport and the regulation of big business. Neither is the left looking towards the Labour Party. Since the high tide of Bennism in the early 1980s the left has been all but eradicated from the Labour Party. There now exists a large floating population of left wingers, many of whom have already left or been driven out of the Labour Party, and others who remain members but keep their heads down, who are looking for a socialist alternative to Blairism. They are enthused by the new mood of resistance symbolised by the anti-capitalist demonstrations and share its values. Many are already activists in single issue campaigns. But they are increasingly looking for a broader political response to the failures of the government, for a socialist response that can help rebuild the left. It is in this context that another point made by J.T. Murphy is worth recalling:

Nor should it be forgotten that crises have their beginnings in centres other than those of the industrial organisations. Repeatedly we have witnessed proposals and measures being introduced into parliament that, when put into operation, would vitally affect the movement outside parliament ... without the slightest agitation in the industrial and social life of the masses. Had there been revolutionaries within parliament in living contact with the organised movement outside parliament ... these measures would have been the signal not only for protest within parliament but for rousing the masses and mobilising their forces for struggle outside parliament. [21]

The point that Murphy makes about the role of MPs can also be made generally about the relationship between electoral politics and direct struggle. Conducted by principled socialists, election campaigns can reinforce, even initiate, protests, demonstrations and strikes.