Carlos Hudson Archive | Trotskyist Writers Index | ETOL Main Page

From Labor Action, Vol. 12 No. 2, 12 January 1948, p. 4.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

If you cannot fairly call the present situation prosperity for the masses, neither can you call it a depression. It is not a depression when over 60,000,000 are employed, many of them at the highest peacetime dollar Wages they ever received. It is not a depression or recession when steel, automobiles and many other heavy industries have markets for all they can produce, and more.

What you might call it is a period of feast-and-famine – a feast for the rich and famine for the poor. It is a depression-without-unemployment. A real depression is what we shall see in “X” years – when both the market at home and the market abroad for U.S. goods have exhausted themselves and when even the mighty resources of this nation can no longer afford to be given away in the effort to save the dying system in Europe.

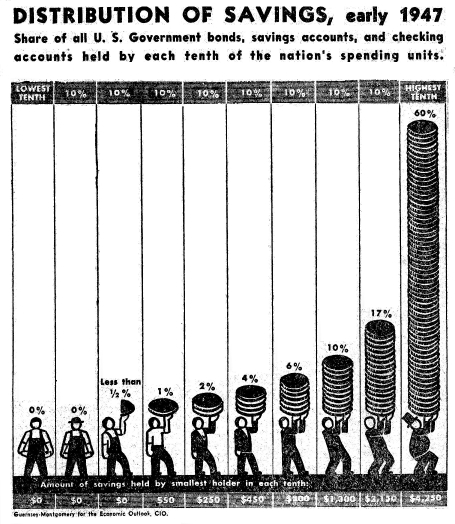

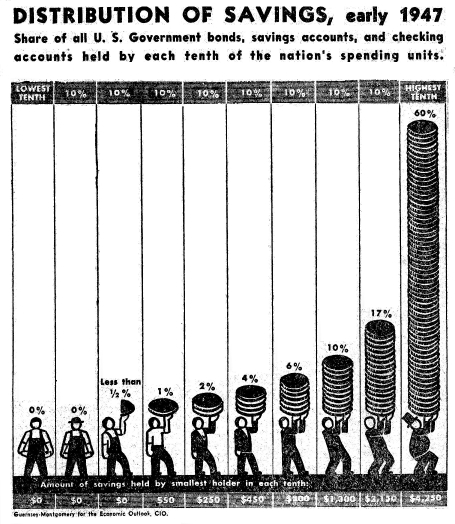

The present domestic market is a strange one. Following the end of the war in 1945, most American industries, unlike the atom bomb plants, reconverted and began turning out civilian goods. Millions of war workers who had been forced to purchase government bonds and thus to save, cashed in their bonds in 1946 and early 1947, and bought those items which they needed – a new washing machine to replace the old one which had broken down during the war – a “new” second-hand car to transport them to the factory or perhaps to move them and their families to a different community – or a store, or furniture, or they spent it for a deferred operation in a hospital or at the dentists.

Today the American workers have almost exhausted their savings, through such purchases and through long periods of unemployment due to strikes, and through the high cost of living. They are priced out of the market, for all but basic necessities. This is a key fact in any analysis of the economy: The masses are priced out of the market, and require all their wages just to live from day to day.

This situation is veiled from the public and the reason that it is hidden is that the upper middle urban Classes and the upper middle farmers are so extremely well-off due to their enormous incomes and profits that they are still able to buy up a very large proportion of heavy consumer goods that come on, the market. What they don’t buy is being sent abroad.

What else has served to carry the post-war economy thus far without shattering resumption of the pre-war depression?

1. In 1930 American military expenditures were negligible. Today these expenditures exceed the total pre-war national budget, assuring orders for steel, chemicals, planes and other heavy goods.

2. A second factor which has helped keep up consumption is the increased volume of consumer credit, or buying on time. The volume of consumer credit outstanding increased $221 million in June 1947 to bring the total to $10.8 billions, a figure 38 per cent above that of a year ago.

The AFL in a recent analysis of the current economic situation pointed out that while the volume of goods and services produced rose by $6.4 billion in the first half of 1947, consumer income aftet taxes rose only $1.6 billion. “Because their income did not rise enough to compensate for high prices,” the survey stated, “consumers spent a billion dollars out of wartime savings and borrowed half a billion through instalment buying and other forms of consumer credit.”

The federation concluded, and correctly, that prices would not come down, that the then pending cashing of terminal leave bonds (about $1.8 billions) would be just a shot in the arm to maintain consumer demand, and that therefore workers must increase their consuming power on their own hook. To this end it advocated that union members organize cooperatives and credit unions to raise buying power. But, obviously, this too would be “just a shot in the arm.”

Instalment buying will increase, just as it did prior to the 1929 crash. A recent survey on instalment credit by the Northern Trust Co. predicted just this – a steep rise in instalment buying. Last year, according to the survey, between four and five per cent of the total retail sales in the U.S. were made on an instalment basis. This is still relatively low, compared with an average of twelve per cent for the three years before our entry into the war. Prior to the war, about sixty per cent of new and used cars, more than fifty per cent of the dollar sales of household appliances, and about fifty per cent of furniture sales were on the instalment basis. The trust company observed that a low-priced car could have been financed in 1940 with a cash payment of $320, about one-third of the purchase price, and 18 monthly payments of $43 each. But today, the down payment amounts to about $500 and the monthly payments over the 15 months allowed by the government amount to $76 each.

Credit granted to instalment buyers increased by $170 million in October, a Federal Reserve Board report issued in December showed. That lifted the total instalment credit oustariding to $5,454,000,000. The all-time record, set shortly before Pearl Harbor, is $6,000,000,000. Total consumer credit, which includes charge accounts and loans repayable in a lump sum as well as instalment transactions, increased $79 millions in October 1947 to a new record high of $1 billion.

Within two short years after the war, the masses have had to go deeper into debt than ever before in history, just to keep their heads above water. It is a dark harbinger of, the future.

3. A third factor that has served temporarily to stave off the resumption of the 1929–40 depression is the unprecedented volume of investments for new plants and equipments. In its recent monthly bulletin the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia stated that such expenditures are running at a record annual rate of $16 billions, >MORE THAN THREE TIMES THE ANNUAL AVERAGE FOR THE 20 YEARS PRECEDING THE WAR. (In 1939 dollars, $16 billions melts down to about $10 billions.)

From such vast capital expenditures the money spent comes back in some measure to the working class, in the form of wages for building construction men, toolmakers, etc. So the temporary affects of capital expenditures sustain the economy. But if U.S. foreign trade should drop off to pre-war levels, if domestic consumption should dry up much more, if a depression should start, all this vast new plant and equipment would be shut down, with even more shocking affects than if it had never been built.

4. Yet another factor that has served the current business boom is the extremely large expenditures by business for inventories of goods. I have harped upon this often in my column, and won’t add much here, save to observe again that the stores and warehouses and rail freight depots and manufacturing plants are bursting at the seams with goods, with inventories the highest in history. Business inventories boomed over the $40 billion mark in September, and grew at an even faster clip in October.

“Government officials have become increasingly concerned about the rate at which inventories have been climbing,” stated the N.Y. Journal of Commerce. Retailers, the officials pointed out, accounted for over half the September rise in inventories, but retail sales did not rise as rapidly as inventories. This mountain of goods is suspended over the heads of the nation out of reach of the masses, but destined at a certain point to back up in the factories, crowding out the workers and their jobs. Manufacturers can no longer count on inventory demand to support the production, the Department of Commerce recently warned. It said that the end of the post-war inventory boom was at hand and that one of the strongest props of the post-war economy is vanishing. President Truman, in his midyear economic report of July 21, acknowledged that “this unprecedented prosperity” is based largely on “temporary props,” which he summarized as follows:

5. On this last factor of foreign trade: Between the First and Second World Wars, the U.S. became first among its imperialist peers in the matter of foreign trade and foreign investments. In 1939 the U.S. had a little more than fourteen per cent of the total exports of the world, and more than eight per cent of the imports. But in 1946 the U.S. recorded thirty-seven per cent of the exports, and twenty per cent of the total imports. Dollarwise, in 1946 U.S. exports totaled $15.1 billions, while imports ran to $7.1 billions. For 1947, the National Foreign Trade Council estimates, U.S. exports will hit $18-$20 billions, and imports $8 billions. The U.S. government estimated that imports wouldn’t go over $5 billions, and it was the more accurate estimate.

U.S. exports currently represent nearly ten per cent of the nation’s production. If this ten per cent were lopped off, it would mean an addition of, more than 2,000,000 industrial workers to the unemployed rolls, that is, a doubling of present unemployment. This would begin to constitute a heavy drag on the entire economy.

Rather than risk this, U.S. imperialism prefers to give away the difference between its exports and its imports. The question arises, who shall it be given to? Naturally, Washington prefers to give it away to the best political purpose, that is, to weaken the position of its leading imperialist rival, Russia. This is one of the factors that looms very large in the calculations behind the European Recovery Plan. The reason Truman had to rush part of the plan along through a special session of Congress is because of the painful dollar “famine” abroad.

Who will pay for these billions of dollars of gifts made to bolster up reactionary governments in Europe and Asia, and to keep the capitalist system staggering along here at home? The American people will pay for them in the form of yet higher prices and higher taxes. Of course there is not the slightest guarantee that such gift loans will permit the capitalist system abroad to revive. The ERP, which will drain off huge amounts of goods from the U.S., will serve to keep prices high at home, and indeed to push them still higher than they are at present.

What does all this adds up to?

Our present hopped-up economy is based on several clearly-defined factors – pent-up consumer purchasing power from the years of war scarcities; tremendous peacetime military expenditures, a by-product of the atom plants; swollen and artificial exports; the building up of huge inventories of goods at all levels; increasing instalment buying; heavy capital goods investments.

We have looked at these factors individually, and concluded that most are nearing the point of exhaustion. Some of the factors can be kept alive for a period of time. The European Recovery Plan can keep exports flowing. Loosened credit restrictions can keep consumer goods flowing for a brief period. The huge national debt of about $259 billion doesn’t leave much room for tax cuts, but some relief is possible and might help (the catch here is that Congress is ready to give tax relief – but only to the wealthy; who can already afford to purchase all they need and still set aside huge sums for savings and investment and speculation).

But the big props of the post-war economy have been washed out – the pent-up consumer purchasing power in the form of war bonds and savings in the hands of the masses; the dollar credits amassed in Latin America during the war; the building up of inventories; the heavy capital goods investments.

Prices will continue to rise until the big turn comes. The pending huge increase in rail freight rates and the launching of the ERP alone guarantee this. When the depression comes, it will be world-shaking. In the U.S. plant capacity has doubled since 1929. The population is up ten per cent. The masses are better organized, a little wiser, a little harder to control by the old methods. The economy is more monopolized. Military commitments are greater. The national debt is many times larger, even BEFORE the depression begins.. The farm capacity is greatly increased. The rest of the world is insolvent. The unrest in the colonial world continues to grow. How near is the crack-up? Here is one figure which, if taken alone, |a positively frightening in its implications. According to a recent article by Ray Moulden in the Chicago Journal of Commerce, “economists most listened to in the financial market ... think there is only a very slight edge of demand over supply, not more than a ratio of 101 would-be durable goods buyers for each 99 items. They believe this delicate situation could very easily change and that the first sign of equalization will start cutbacks throughout production lines, with unemployment coming first, then price declines,”

It would be a gross error, however, to believe that we are that close to the precipice. The government still has resources at its command – tax cuts, a third round of wage increases, a veterans’ bonus, further relaxation of credit controls, still larger export gifts. All are palliatives, all will make the day of reckoning so much sterner, but all help rouge the cheeks of the patient to keep him looking as big as life and twice as natural.

There’ll be many a bourgeois economist to dispute the above analysis publicly, should it come tp his attention. Privately, it’s another matter. And there are myriad signs that important figures in the upper world have lost hope in the system and are resigned to a smash-up.

A sober conservative economist like Roger Babson purchase’s an abandoned lead mine in Kansas, where he plans to establish a select community which might survive the threatened war of fissioned atoms and deadly bacteria, and which might issue forth at the end of the war to begin anew the centuries-long task of rebuilding the same old system that today tortures most of mankind and condemns it to lifelong insecurity.

There is the economist Ralph Borsodi, whose strange book, Inflation Is Coming, is today so widely advertised and sold. What does Mr. Borsodi predict? “Inflation, national bankruptcy, nation-wide unemployment, world-wide business depression.”

He likens the present situation, with its inflated currency to a community living at the foot of a gradually crumbling dam, behind which is the irresistable onrushing force of inflation. His advice: Head for the hills, boys, the dam is doomed. Government securities are worthless. Dig in on a homestead and try to weather the storm.

Since Mr. Borsodi wrote his book, in 1945, the money in circulation has increased still further, to a total of $28,817,000,006 the week ended December 3, 1947. Incidentally, of this total, the Federal Reserve Board can account for only $17 billions – a measure of the vast money hoarding on the part of the rich, to escape taxation. I do not agree with Mr. Borsodi’s analysis, and will criticize Inflation Is Coming in an early column in Labor Action. I mention the book here only as an aid, in establishing the prevalent mood among thousands of capitalists.

The columns of the nation’s financial press literally read these days like the ravings of a maniac. One day they are full of sunshine and hope the next day the same paper, even the same writer, issues such gloomy forecasts that the very weather ceiling touches the ground. Such a column is that written not so long ago by Ray Moulden, head of the Washington bureau for the Chicago and New York Journals of Commerce. Moulden is an able, sensitive and sympathetic reporter of capitalism, with broad contacts. His colurnn is worthy quoting – especially, to those of faint heart in and out of the radical movement, those who insist on giving an unlimited letter of credit to capitalism; and to those young friends who have read a lot of Keynes and nothing at all of Marx and who say, like the infant at its mother’s breast: “Mama is the best cook.”

Here is the column:

“To many businessmen walking the tightrope of inflation, the major question of the day is no longer if, but when will the crash come and how far will they be carried in the fall. Few practical men who most concern themselves daily with the struggle to buy materials, arrange for their fabrication and to merchandise the resulting product, can see anything ahead but chaps ...

“They appear to be economically trapped. If they continue to do business they must involve themselves so far ahead at speculative prices in order to insure material supplies that each such protective venture indicates a worse position when the break occurs. Many of our largest firms are wondering how much further they can thus extend themselves without unduly jeopardizing stockholders. Once they become convinced they can no longer take these -risks, they themselves will supply the downward incentive by their very contraction. And they know it well.

“The Marshall Plan seems to insure a relatively high level of exports, for a fair number of years, which, coupled with labor costs and federally supported farm prices, indicate continued high prices. But at some point in this spiral the consumer is going to stop buying ...

“Never have there been so many speculators in all producing centers buying up anything they can get their hands on to hold for a premium later ... Once a price break comes, of course, these speculators will unload heavily, but the legitimate merchandiser and manufacturer will be stuck with his high-priced goods bought to insure supplies and the necessity to get a fair return oil the product made from them.

“If the break is delayed for many months, this trip across the tightrope becomes more and more shaky, the tension mounting with the risk.

“So what executives are asking themselves is how long can this situation go on before someone or something cracks, and the whole edifice comes down? At what point will boards of directors call a halt to over-expansion and competition with speculators and call it a day, starting the contraction that can only result in an enforcedly self-made toboggan?

“None can see any way out of the maze. Even those most inclined to be isolationist and to say we should. sever the world contracts that are contributing to the debacle admit we cannot cut loose from Europe. We must support the rest of the world for fear its economic failure will break us; yet in the process of insuring our safety we may be smashed financially anyhow.”

|

Carlos Hudson Archive | Trotskyist Writers’ Index | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 23 December 2015