Nigel Harris Archive | ETOL Main Page

From Socialist Worker Review, No.94, January 1987, pp.6-7.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

|

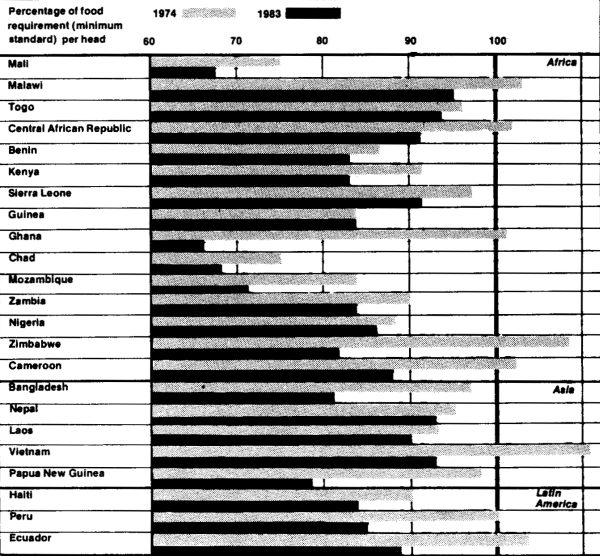

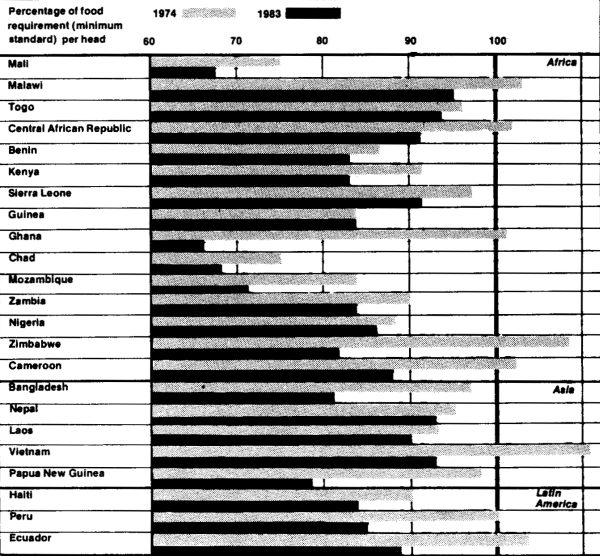

THE CAMPAIGN for famine relief in Ethiopia and Sudan had the merit of spotlighting the terrible conditions there. But it had the bad effect of concealing just how many other countries were starving or close to starving. The chart shows the countries where the average calorie intake has fallen below what is considered medically the minimum between 1974 and 1983.

The chart does not include all the countries that, in 1984, had insufficient food per head; 44 of the 96 main developing countries were in that position. And it does not include some key famine cases, for example Ethiopia and Sudan, because they improved their position between 1974 and 1983 – from 82 to 93 percent for Ethiopia, and 88 to 90 percent for Sudan.

Above all, the figures do not tell you who actually eats what; the figures are based upon the availability of foodstuffs, not the availability of money to buy the foodstuffs.

However, despite these severe weaknesses, the chart does show that a lot of countries now have access to only four fifths of what food is needed to maintain a minimum standard of life (and it is a pretty austere minimum). And it highlights some catastrophic cases – Mali, Ghana, Chad. Ghana is especially extreme – like, to a lesser extent, Zimbabwe – because of the disastrous fall between the two years.

It also illustrates one of the elements in the growing import of foodstuffs by developing countries. Between 1970 and 1984 these imports increased 71 percent. Now there is no harm in food imports – indeed, the enhancement, enrichment and diversification of diets requires increasing trade – provided developing countries have an equal opportunity to export those goods where they have an advantage.

That is the problem. Agriculture is one of the most extreme cases of tight control within world capitalism – indeed, a new theory of imperialism could be based upon the control of foodstuffs rather than capital or manufactured goods. And it is here where we can identify one of the most powerful sources of famine.

The good citizens of Europe, North America and Japan pay roughly an extra £51,000 million annually to subsidise food production at home. The Europeans, especially generous in this respect, pay about £66 for every man, woman and child in Europe each year.

As is notorious, this prodigious open handedness has built mountains and lakes of surplus foodstuffs, now sufficient to feed the whole population of Africa five times over. World cereal stocks are approaching 200 million tonnes – when the countries of the Sahel region in Africa needed only 3 to 4 million tonnes to keep their starving alive.

The size of European foodstocks is at last becoming insupportable. The value – £8,760 million – is notional, because if an attempt were made to sell the stocks, world prices would crash so low that less than half the notional value would be recovered.

The cost of storage is now coming to exceed the value of what is stored. Take, for example, the one and a half tonnes of butter (ten pounds a head of the European population). It costs £143 million per year just to keep it – and even then an unknown quantity is deteriorating into nasty butter oil.

No wonder the EEC is so desperate to offload the stocks in any way at all provided it does not reach needy consumers in Europe. They are now selling butter stocks at under 3p per pound (as against £1 per pound on the European retail market) to be fed to calves. And this year the Russians will be given a £143 million subsidy to take EEC butter.

This astonishing heap of corruption is not, however, the problem, nor simply the way in which European governments oblige their inhabitants to pay astronomical prices to produce foodstuffs that must be in the main pure waste. The real problem – and where it connects with famine – is that the EEC subsidises agricultural exports.

Europe spends £3-4,000 million annually to dump foodstuffs on the world market – which then wrecks the export markets of developing countries. As a result, developing countries are denied the opportunity to earn the revenue that allows them to buy grain (even though prices are now desperately low) to offset famine.

Take, for example, sugar. Because of the subsidies, the EEC has now become the largest exporter of sugar in the world, even though, compared to sugar cane growers, sugar beet producers are very inefficient. In the sixties Europe supplied about 8 percent of world sugar exports; in the eighties, over 20 percent.

The scale of subsidies is scarcely believable – especially, compared to Mrs Thatcher’s notorious views on social spending. In mid-1984, when the EEC exported sugar at £93.50 per tonne, it was buying it from European sugar refiners at £346.50 per tonne. The subsidy – of £253 – was nearly three times the value of the sugar on the world market. You wonder why they don’t just pay the money and cut the sugar out altogether.

Such a scale of subsidy is death to Third World producers. On the island of Negros in the Philippines there is a famine because of the mass sackings that have resulted from the low sugar price that Common Market exports have caused. Filipino exports – 2.6 million tonnes in 1977 – were 600,000 in 1985.

Mozambique is now an endemic famine area; 100,000 are said to have died in the famine three years ago, and over three million people are at risk in the season 1986-7.

Mozambique’s sugar exports, running at nearly 200,000 tonnes in the early eighties, were 23,000 tonnes in 1985. Mauritius depends for 65 percent of its export earnings on sugar, not to mention Jamaica. The World Bank reckons the developing countries are losing about £5,400 million per year because of the agricultural policies of the More Developed Countries.

The EEC is doing the same thing with olive oil, wrecking the export markets of Tunisia and Morocco. Argentina’s debt crisis is vastly exaggerated because the EEC has taken to dumping wheat and beef in key Argentinian markets (beef exports from Argentina have fallen 40 percent in the past 15 years).

Brazil has been hard hit in the sugar market where it is one of the cheapest producers (production costs are under half Europe’s) – earnings from exports of sugar fell by 56 percent between 1979 to 1983. The United States has launched a major programme to subsidise rice exports to the severe loss of the world’s largest exporter, Thailand.

World agricultural trade has become dominated by these monstrous conspiracies that simultaneously rob the consumers at home (particularly hitting the poor through high food prices) and wreck the markets of developing countries, so forcing famines on them. The price of hunger is growing abundance of wasted food. And on top of that, the system does not even protect the farmers.

Since the early seventies the income of British farmers has been halved and their debts doubled (they may total £8,500 million this year). The Mid West of the United States is now being reduced to a new rural dereliction as family farms fold under the weight of debt, followed by the towns, villages and factories they supported. The only gainers are a handful of the largest farmers (usually companies), and big processing, storing or trading companies.

Now, more than ever, the struggle to rid the world of famine starts here – not with the begging bowl and pleas for pity, but by breaking the criminal conspiracy of the Common Agricultural Policy.

Nigel Harris Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 10 April 2010