Alex Callinicos Archive | ETOL Main Page

From International Socialism (1st series), No. 104, January 1978, pp. 5–8.

Transcribed by Christian Høgsbjerg, with thanks to Sally Kincaid.

Marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

1977 was a year of reviving militancy among rank-and-file workers. A wave of unofficial strikes shook the Social Contract. The Grunwick strike gave workers’ anger a national focus. And the firemen took on the Labour government. Alex Callincos reviews these struggles, and draws the lessons.

The Labour government is now involved in its biggest confrontation with any section of workers since it came to power in March 1974. The outcome of the firemen’s strike (which was still uncertain at the time of writing) will determine whether or not other sections of workers follow their example and press ahead with their wage claims in defiance of the government’s ten per cent limit.

The firemen’s strike, then, could be a turning point in the present wave of struggles against the Social Contract. The aim of this article is to review these struggles and draw some conclusions about future prospects.

1976 was one of the bleakest years in the recent history of the British labour movement. Unemployment reached the highest levels since the 1930s. Workers suffered the biggest fall in their real wages this century. Social services were slashed on the orders of the International Monetary Fund. A wave of racialism convulsed the cities of England.

Most seriously of all, British workers, after reaching heights of militancy under the Heath government unparalleled since the days of the General Strike, on the whole acquiesced in these attacks. Strike figures slumped. The TUC gave massive support to Labour’s pay policy. Those workers who wanted to fight – grouped mainly around the Right to Work Campaign – found themselves isolated, pushing against the stream.

The situation changed very rapidly in early 1977. A spontaneous and massive rank-and-file rebellion against the Social Contract led to a number of major unofficial strikes – Leyland, Port Talbot, Heathrow. The trade union bureaucracy found itself forced to retreat from its previous unconditional support for the pay policy to a much more qualified policy. And the strike figures shot up.

These are the figures for stoppages of work in Britain over the last decade:

|

Year |

No. of stoppages |

Disputes in progress |

Working days lost |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1968 |

2,378 |

2,258,000 |

4,690,000 |

|

1969 |

3,116 |

1,665,000 |

6,846,000 |

|

1970 |

3,906 |

1,801,000 |

10,980,000 |

|

1971 |

2,228 |

1,178,000 |

13,551,000 |

|

1972 |

2,497 |

1,734,000 |

23,909,000 |

|

1973 |

2,873 |

1,528,000 |

7,197,000 |

|

1974 |

2,922 |

1,626,000 |

14,750,000 |

|

1975 |

2,282 |

809,000 |

6,012,000 |

|

1976 |

2,016 |

668,000 |

3,284,000 |

|

1977* |

2,309 |

915,000 |

17,415,000 |

|

|

(1,714) |

(566,400) |

(2,769,000) |

|

* 1977 figures only cover first ten months of the year. |

|||

1977, then, has been the year in which workers began to fight back. To see why the strike figures shot up, we need only have to look at another set of statistics.

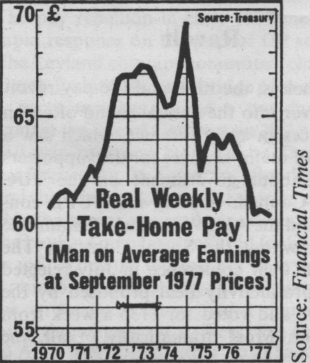

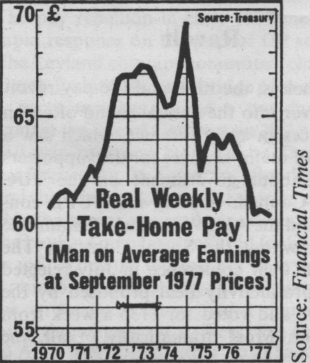

This graph shows what has happened to workers’ real wages in the last seven years.

|

In September 1977 the real weekly take-home pay of a married man on average earnings was £60.35 compared to £60.70 in June 1970 (calculated at September 1977 prices). In other words, his real wages were lower than when Labour lost the 1970 general election. Real wages reached their peak, £69.22, in December 1974, during the 1974–75 ‘wages explosion’ which followed the fall of the Heath government. Since then they have fallen by 12.5 percent. (Financial Times, 6 December 1977)

September 1977 was also the month when 1,240,000 working days were lost – the highest figure since November 1974, the height of the ‘wages explosion’. (Department of Employment Gazette, November 1977)

Faced with this revival of militancy among British workers, the Labour government has fought to hold the line in defence of its pay policy. For Callaghan and Healey this is a matter of survival.

Elected to implement ‘an irreversible shift of wealth and power in favour of working people’, the Wilson and Callaghan administrations have set themselves the task of restoring the competitiveness and profitability of British capital. The crux of this strategy has been the massive transfer of resources from the consumption of the working class (wages and social services) to the profits of capital. Wage controls, cuts in public spending, tax subsidies for big business, the devaluation of the pound – all have had the aim of boosting private profits. In 1976, the first full year of Labour’s pay policy, the gross trading profits of all industrial and commercial companies rose by 27 per cent, from £11.5 billion to £14.6 billion.

But the government has been less successful in its attempts to translate this rise in profits into a reversal of Britain’s industrial decline. Its main success – the rise in the pound and the massive inflow of money into Britain in 1977 – was financial, and did not affect the depressed state of British industry. Indeed the money attracted to the City by the prospect of a rising pound threatened to increase the money supply faster than the 9-13 per cent limit imposed by the International Monetary Fund.

The government’s response was to allow the pound to rise freely on the foreign exchanges and to raise the minimum lending rate (which determines the rate of interest on money loans) from five to seven per cent. These moves threaten to kill any economic revival at birth. One economist, William Eltis, argued recently that the previous fall in the pound, by making British goods cheaper on world markets and exporting more profitable, had laid the basis for export-led growth:

‘In June, July, August and September 1977 the volume of exports was 14 per cent above the level in the same months of 1976 while imports were up hardly at all. This produced a staggering balance of payments improvement ... Oil was responsible for only about one-third of the improvement. Britain actually increased its share of world exports of manufactures from 8.6 per cent to 9.8 per cent in just one year, a notable achievement for a country which had 16 per cent of the world market in 1961, 12 percent in 1967 and just 8.8 per cent in 1974.’

However, ‘in the past few weeks the government has been busily throwing away the fruits of this export-led-growth strategy. The rise in sterling value will undermine the export boom. The benefits from lower costs that it produces will be small in relation to the damage to exports. The higher interest rates will undermine the investment boom. With exports and investment stagnant as a result of these new policies, unemployment will remain high throughout 1978’.

Eltis also highlighted British industry’s desperate need for new investment:

‘Recently published figures show that on a replacement-cost basis, real net manufacturing investment was £1,040 million in 1970, £791 million in 1974 and £365 million in 1976, a staggering fall of 65 per cent. We are investing about 5 per cent more in 1977 than in 1976 which means that we are still investing 60 per cent less than in 1970.’ (Sunday Times, 4 December 1977)

A recent survey in the Economist predicted a mere 6 per cent increase in manufacturing investment in 1978. It also highlighted the reason – despite the dramatic increase in profits in 1976, the real rate of return on capital was 3.3 per cent, compared to 3.2 per cent in 1975 at the height of the recession. (Investment in Britain: A Survey, Economist, 12 November 1977). Profits are still too low compared to the cost of new investments.

The Labour government must, therefore, continue its attacks on working-class living standards. If the profitability of British capital is to rise to a level at which large-scale investment will take place then the rate of surplus-value must be forced up even further. Continued wage-controls are essential to achieving this aim.

The scene was, therefore, set for a major confrontation between the Labour government, committed to defending the pay policy at any price, and the rank and file of the labour movement, rebelling against the fall in their living standards.

Indeed, the first few months of 1977 saw such a rebellion developing. When Industry Minister Eric Varley visited British Leyland’s Longbridge plant in February 5,000 car workers turned out to express their opposition to the Social Contract. Spring was marked by a series of major strikes, against the pay policy – the Leyland toolroom strike, the Heathrow engineers’ strike, and the Port Talbot electricians’ strike.

However, these strikes did not lead to a general breakthrough. The central reason for this fact was the role of the trade union bureaucracy. The TUC General Council had provided the backbone of the Social Contract during the previous two years. The revival of wage militancy among their members meant that the trade union leaders were forced to effect a tactical retreat. They could not explicitly support a rigid Phase Three ceiling on wage increases similar to the six pound limit and the 4.5 per cent limit. However, at the same time they did their utmost smash rank-and-file opposition to the pay policy.

The trade union bureaucracy’s defence of the Social Contract was carried out under the watchword of ‘an orderly return to free, collective bargaining’ – with the emphasis on ‘orderly’. The operation involved ‘left’ and right officials alike – Hugh Scanlon at Leyland, Frank Chapple at Port Talbot, Reg Birch at Heathrow. It benefited also from factors to which we will return – the erosion of shopfloor organisation and the degeneration of the Communist Party, which opposed both the Leyland and Heathrow strikes.

Nonetheless, the rank-and-file pay revolt spilled over into the annual round of union conferences in early summer, which saw a number of major reverses for the supporters of the Labour government on the TUC General Council. In May the NUPE conference and the AUEW National Committee both threw out the Social Contract. The miners at their conference in July rejected the pit productivity deal proposed by the Executive and voted for £135 a week from November. Most dramatically of all, the TGWU conference ignored Jack Jones’ pleas (an unheard of indignity for the general secretary of the T and G to suffer) and voted for an immediate return to free, collective bargaining.

If these conference decisions had been observed at the TUC in September, then a wage explosion of 1974-75 proportions would have been inevitable. The General Council’s resolution was aimed at staving off such an explosion. Although it did not give explicit backing to the 10 per cent maximum increase in earnings laid down by Healey, the resolution did make the twelve-month rule official TUC policy. The resolution was carried, thanks mainly to Hugh Scanlon’s willingness to invoke Carron’s law and overrule the AUEW delegation and union policy laid down by the national committee.

The TUC’s decision on the twelve-month rule permitted the official movement to swing round behind the government. Jack Jones, Alan Fisher and other union leaders were able to overrule their conference decisions opposing wage controls on the basis of ‘TUC solidarity’.

The trade union leaders’ continued support for the Labour government is indicated by these figures, which show what percentage of working days lost in the first seven months of 1977 were due to official strikes:

|

January |

|

4.3 |

|

February |

4.3 |

|

|

March |

7.8 |

|

|

April |

1.1 |

|

|

May |

1.0 |

|

|

June |

1.0 |

|

|

July |

6.3 |

|

|

Source: Department of Employment Gazette |

||

Although more recent figures were not available at the time of writing, the picture is unlikely to have changed radically – the pay rebellion in 1977 was largely an unofficial movement opposed by the trade union bureaucracy.

The trade union leaders could not stem the tide completely. September in particular saw a wave of strikes, ranging from the national bakers’ strike over holiday pay to a rash of pay-claims. A number of victories were chalked up, most notably by the British Oxygen strikers, who crashed through the ten per cent limit to win a settlement which amounted to a wage rise of 25 per cent on previous wage levels. By the beginning of November the CBI was signalling its concern at the number of phoney productivity deals (like that at BOC, which included a £5 bonus for ‘past productivity’) conceded by private employers as a way of circumventing the ten per cent limit.

But, as significant as the battles which were won, were those that were not taking place. A number of the traditionally best organised sections – dockers, miners, carworkers – were notable by their absence from the strike figures.

It was not as if these sections were not affected by the rank-and-file rebellion against wage restraint. Leyland carworkers had, in fact, spearheaded the rebellion with the Longbridge demonstration in February and the toolmakers’ strike. An indication of the militancy of the strong sections was the support they gave to the Grunwick strikers. The 11 July mass picket and demonstration at Grunwick represented the biggest national mobilisation by the traditional core of working-class militancy in Britain – the mines, the docks, the car industry – since the days of the Heath government.

Yet the big battalions who turned out in support of strikers drawn largely from the most oppressed and ‘backward’ section of the British working class – Asian women – have not, as yet, moved into battle for their own pay claims.

The car industry set the pace for wage settlements in other industries during the boom of the 1950s and 1960s. 1977 was, indeed, the year of the Leyland and Vauxhall toolroom strikes. But it has also seen the acceptance by Ford workers of a pay deal only slightly above the ten per cent limit; the collapse before it had begun of the Longbridge strike against the Social Contract; the two to one victory for management in the Leyland ballot on corporate bargaining; the failure of the Jaguar strike against the pay policy; the decision by shop stewards at Chrysler Linwood not to challenge the pay policy.

The dockers smashed the Industrial Relations Act in 1972. In the summer a national dock strike was on the cards. By September the retreat had been sounded.

The miners destroyed two successive pay policies in 1972 and 1974 – in the process bringing down the Heath government. Again, it now seems unlikely that the miners will take strike action in support of their demand for £135. This is almost certainly guaranteed by the decision of the right-wing majority of the NUM Executive effectively to implement the pit incentive scheme overwhelmingly rejected in October’s ballot by allowing areas to go ahead with their own productivity deals and to observe the twelve-month rule which the miners’ conference threw out in July. The fact that miners in some areas will earn more cash thanks to the productivity deals will inevitably take much of the steam out of the national pay claim and undermine the unity of the areas which opposed them in the ballot.

A number of reasons explain the unwillingness of these strong sections to move into action against the pay policy. Two factors are of particular importance.

First, there is the erosion of shop stewards’ organisation. Particularly in those industries – cars, engineering, shipbuilding – that formed the centre of wages militancy in the 1950s and 1960s, shop-floor organisation has emerged from the recession seriously weakened.

In part, this reflects the nature of the organisation built up during the boom around sectional struggles – battles within individual sections or factories over wages, hours, and conditions. Because shop stewards’ organisation was fragmented, geared to fight this sort of localised dispute, it was also, naturally, reformist – real improvements could be wrung out of employers in conditions of full employment without any need to confront the capitalist state.

The recession brought with it a much more drastic challenge to shop-floor organisation than it had faced before – the fight to defend jobs and living standards now involved confronting, not simply the employer, but also the Labour government, and in conditions, not of prosperity but of slump, as lay-offs and short-time working cut jobs and wages. Moreover, the recession highlighted and accelerated the process of differentiation taking place within shop stewards’ organisation – the emergence of a layer of full-time convenors and senior stewards divorced from the shop floor. Particularly in the car industry the years since 1974 have seen this layer drawn into ever closer collaboration with management through a variety of schemes for ‘workers’ participation’.

Closely related to this factor is a second one – the degeneration of the Communist Party. In 1977 the CP moved sharply to the right. The party’s congress in November approved a revised version of The British Road to Socialism, which represented a new stage in the CP’s transformation into a reformist party of the traditional social-democratic type.

The Communist Party’s march rightwards has a serious impact on the struggle against the pay policy. The late 1960s and early 1970s saw the CP-dominated Liaison Committee for the Defence of Trade Unions lead significant unofficial strikes against Labour and Tory attacks on workers’ organisation. But in 1977 the story was a very different one.

Two examples will illustrate this change. The pay rebellion in early 1977 met with a rapid response on the part of CP stewards. The Leyland combine committee, chaired by Derek Robinson, Longbridge convenor and a party member, called a one-day strike against the Social Contract on 20 April. This call was endorsed by a Liaison Committee conference on 26 February. But Robinson and the other initiators of the strike call were also the senior stewards closely involved in the Leyland management’s bid for ‘industrial peace’. When the toolmakers went on strike, Robinson (supported by the CP) denounced the strike and even signed a management letter threatening the strikers with dismissal.

20 April was turned into a ‘day of action’ – it proved to be a damp squib, with little support in Leyland.

The same pattern of rhetorical militancy followed by abject retreat was repeated in August over the Longbridge pay claim. Strike action was called off abruptly after a ‘give us work’ demonstration by one section, despite a two to one majority for the strike.

The final blow came when Robinson and the CP gave effective backing to the Leyland management’s scheme for corporate bargaining despite its aim of gutting shop-floor organisation. A pamphlet called British Leyland – Save It! written by John Bloomfield, Birmingham city secretary of the CP and with a preface by Robinson, endorsed the management’s strategy as part of an ‘alternative economic policy’ to save British industry. And when the result of the ballot was announced – 59,029 for the scheme, 31,043 against – Robinson declared ‘we will welcome the opening of negotiations as soon as possible’ (Morning Star, 1 November 1977).

An even more dramatic example of the CP’s decline took place in early December at Govan Shipbuilders. These shipyards were the scene in 1971 of one of the finest examples of solidarity in the recent history of the British working class – the fight workers at Upper Clyde Shipbuilders (as it was then called) to keep the yards open won the support of the whole labour movement and was a turning point in the battles under the Heath government.

At the end of November 1977 British Shipbuilders reallocated work on an order of Polish ships to Govan after workers at Swan Hunter in Tyneside had refused to give into blackmail aimed at forcing them to remove an overtime ban. It was natural to expect that the Govan shop stewards would repudiate this crude attempt at divide and rule with the contempt it deserved. This certainly would have been in line with the Morning Star’s editorial statement that ‘the response to the call from Swan Hunter shop stewards [to black the work taken away from them] should be in the best traditions of British working-class solidarity’.

Yet the response of the Govan shop stewards was a statement by their convenor, Jimmy Airlie, a leading member of the Communist Party in Scotland, that they would accept the work because ‘all the 24 ships must and will be built in British yards’. This statement was published without comment in the Morning Star (6 December).

The pressures on the CP to move rightwards are twofold. First, there is the tendency to accommodate the party’s trade union base, which increasingly is dominated by officials and full-time convenors like Airlie and Robinson. Second, there is the growing strength and confidence of the CP right-wing, which is drawn from a predominantly student and lecturer milieu and is hostile to ‘economism’, i.e. workers’ struggles for higher wages. The right wing emerged from the CP congress with added strength and confidence as result of the gains they made there (notably the defeat of the executive in the debate on the Morning Star). They immediately launched a debate in the letter columns of the Morning Star, which found Ken Gill, general secretary of TASS, and Mick Costello, tipped to succeed Bert Ramelson as CP industrial organiser, defending the struggle for higher wages against the denunciations of some of the right’s leading intellectuals like Alan Hunt and David Purdy, who advocate, in effect, support for incomes policy.

These pressures add up to a growing tendency for the Communist Party to vacate its traditional position as the focus for rank-and-file militancy in British industry. The result has been to weaken the struggle against the pay policy.

It is important not to paint too black a picture. A number of the strikes which did take place revealed the existence of national unofficial organisations able to lead protracted strikes – the lift engineers and British Oxygen are two examples. And if the big battalions did not fight on pay, they showed their militancy in other ways. Workers at Chrysler Linwood sat in to block a management attack on shop-floor organisation. Dockers at the Royal Group inflicted a bitter defeat on management in a dispute over manning. At British Leyland’s Cowley assembly plant militant shop stewards witch-hunted from office in 1974 overturned the right-wing leadership of Reg Parsons in the senior stewards’ elections.

The crucial problem is one of confidence. If one major section took on and defeated the government, an avalanche of strikes against the pay policy would almost certainly follow.

Callaghan and Healey are well aware of this. Therefore, their main aim has been to hold the line in the public sector, making an example of any section of workers who stood out against the ten per cent limit. This strategy met with success (with the partial exception of the air traffic control assistants, whose long drawn out strike led to a fudged settlement which granted more than ten per cent). The power workers’ unofficial overtime ban was broken thanks to a press witch-hunt and scabbing by the managers in the power stations. Even the miners, as we have seen, retreated from confrontation with the government.

The crunch came, paradoxically enough, with the firemen – hardly a group of workers generally identified as militant. The Labour government expected that the firemen would have little stomach for a fight and that the strike would rapidly collapse. A ‘crisis meeting’ at 10 Downing Street, which included those two stalwarts of the Labour left, Michael Foot and Tony Benn, decided to use troops to break the firemen’s strike.

In the event, the government proved to have miscalculated completely. The firemen supported the strike solidly, and rapidly won massive public support, particularly when firemen left the picket line to rescue patients from a fire in an East London hospital. Moreover, the army proved unable to cope with the task of firefighting – on one estimate, the cost of fire losses during the first ten days of the strike was over £200 million, as much as the total losses for 1976. (Time Out, 2–8 December 1977)

Moreover, the executive council of the Fire Brigades Union found itself in difficulty. It had unanimously opposed the strike but had been overwhelmingly defeated at the delegate conference which voted for strike action. The result was a collapse of confidence among the firemen’s official leaders, which made it difficult for them to follow their instincts and get the strike over with as quickly as possible.

The government’s strategy switched to drawing the strike out as long as possible. As the Observer put it:

‘Timing is the essence of the Cabinet’s strategy. The longer the firemen are held at bay, even if they were eventually able to endorse an unhappy compromise, the better the prospects generally for Phase Three. Normally at this stage in the pay round three million workers would have settled, but this year four out of five are holding back waiting to see what happens.’ (27 November 1977)

In other words, if the government are eventually forced to give way to the firemen, by making the strike as bitter and protracted as possible they hope to discourage other workers from following the firemen’s example.

The firemen’s strike could be a turning point for the public sector. The last year has seen a drastic decline of the national movement against cuts in public spending. 80,000 workers turned out on 17 November 1976 to protest against the cuts. 5,000 joined a lobby by public sector unions of Parliament on 23 November 1977. This change is largely a product of how the public sector union leaders have run the anti-cuts campaign. The anger behind the mobilisation on 17 November was dissipated in a series of local protests (dubbed ‘guerrilla actions’ by the NUPE leadership) whose ineffectiveness has led to considerable demoralisation. Nonetheless, considerable militancy remains, shown in a number of local battles, for example, over the closure of Hounslow Hospital, as well as the NUPE conference’s rejection of wage restraint, which would be given a massive fillip if the firemen broke through.

Whether or not the firemen win will depend in large part on the solidarity shown by the rest of the trade union movement. This solidarity will not come from the top – the TUC inner cabinet showed that when the rejected the FBU executive’s appeal to them to lead a general fight against the ten per cent limit (which, after all, is not TUC policy). As usual, the trade union bureaucracy showed that their first loyalty is to the Labour government, not their members. Whether solidarity is forthcoming will depend on the action of the rank and file of the trade union movement.

As we have seen, the traditional leadership of rank-and-file movements in Britain, the Communist Party, is abdicating this role. The gap it has left has not yet been filled.

Rank-and-file organisation cannot be built in the present period on the basis of militancy alone. One reason for the erosion of existing shop stewards’ organisation has been the reformism with which it is imbued – its leaders have chosen to prop up the system rather than fight it. And some of the most significant rank-and-file movements to have emerged this year – the Leyland toolroom workers, the power workers – have been defeated as a result of their sectionalism, their inability to project themselves as part of a class-wide opposition to the government’s policies.

To build such an opposition requires the organised initiative of revolutionary socialists. The Socialist Workers Party has set itself the task of building a national rank-and-file movement that can fight independently of the trade union bureaucracy.

Unfortunately, to declare the need for such a movement is not to bring it into existence. The National Rank-and-File Conference on 26 November provided an accurate indication of the distance which still separates us from a rank-and-file movement with the muscle to translate words into action. The conference was attended by 522 delegates from 251 trade union organisations and represented many of the sections of workers involved in recent struggles. However, its call for a day of action in solidarity with the firemen on 7 December met with only a very patchy response.

The Communist Party remains a much more considerable force in British industry. This strength is not used to do anything – more often it serves to prevent action. A West of Scotland shop stewards’ meeting called by the CP-dominated Clyde district of the Confederation of Shipbuilding and Engineering Unions heard a call from Fred Clenaghan, chairman of the Strathclyde brigade committee of the FBU, for a one day sympathy stoppage – according to the Morning Star ‘the shop stewards’ meeting took no decision on Mr Clenaghen’s call’. (1 December 1977) Again, the Liaison Committee for the Defence of Trade Unions is holding a conference in February – on unemployment!

Overcoming the obstacle represented by the Communist Party will require a serious application of the united front approach on specific issues by the SWP (see Pete Goodwin’s article elsewhere in this journal).

At the same time, class-wide rank-and-file organisations must be built by relating to specific struggles. The firemen’s support committees set up in various localities – North London, Reading, Eccles in Manchester are some examples – shows how this can be done. These committees were built by drawing together rank-and-file firemen with trade union delegates representing other sections of workers to organise practical solidarity. By repeating this initiative in the case of other disputes a permanent network of rank-and-file con-contacts capable of pulling action can be built up in every locality.

Without a revolutionary socialist party rooted in the factories, offices, hospitals, schools the task of building national rank-and-file organisation would be impossible. Such a party is needed to combat the erosion of shop floor organisation, to take the initiatives required to draw the different sections of workers into a national movement and to draw the political conclusions from disputes like the firemen’s strike – the strike breaking role of the Labour government, the treachery of the trade union bureaucracy, the need to smash the capitalist state.

Alex Callinicos Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 24 March 2015