Ian Birchall Archive | ETOL Main Page

From Socialist Review, 14 December 1981-22 January 1982: 11, pp.26-27.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

|

No serious sectarian slanging match is complete without the use of the word ‘centrist’. It is, for instance, one of those terms of abuse used by the smaller left sects in relation to the SWP and to each other. Not surprisingly, many people who are new to left politics regard it as an obscure bit of jargon they’d prefer to do without. Who cares whether one group of 200 people calls another of 300 ‘centrist’? Yet, as Ian Birchall explains at certain points in history the term designates a very important phenomenon. When it was first used by revolutionaries at the end of World War One it applied to organisations with hundreds of thousands of activists. When it was used again, by Trotsky, at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, it characterised a party (the POUM) bigger in Catalonia than the Communist or Socialist Parties (which merged), with five thousand armed militiamen. So what is a centrist? |

‘Centrism is the name applied to that policy which is opportunist in substance and which seeks to appear as revolutionary in form. Opportunism consists in a passive adaptation to the ruling class and its regime, to that which already exists, including, of course, the state boundaries, Centrism shares completely this fundamental trait of opportunism, but in adapting itself to the dissatisfied workers, centrism veils it by means of radical commentaries.’

That is Trotsky’s definition. Revolutionary in form, opportunist in substance.

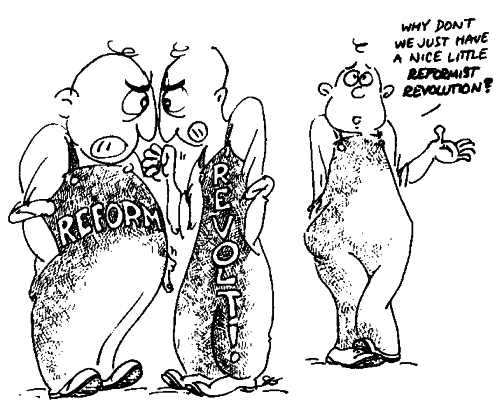

So, for example, Tony Benn, who makes no claim to be a Marxist, is not a centrist. (He’s a middle-of-the-road reformist pretending to be a left reformist.) But many of Benn’s supporters are centrists – they use the rhetoric of class struggle, even to criticise Benn, yet in practice end up reinforcing Benn’s positions.

The substance of Marxism lies in three things: the historical role of the working class, the need to smash the state machine and the need for a vanguard party. And it is on these points that the centrist, despite a rhetorical and sometimes erudite commitment to Marxist terminology, will turn out to be ambiguous.

‘We need the working class, but there are other social forces to be reckoned with in modern society.’

‘The state has to be radically restructured but this needs parliamentary action backed up by mass struggle.’

‘We need a revolutionary organisation, but democratic centralism is hopelessly out of date.’

‘We need a revolutionary organisation, but trade union militants can’t be subjected to total party discipline.’

When you find yourself listening to language like this, it’s probably a centrist talking.

|

Centrism, as a serious political phenomenon, is not a question of naive or dishonest individuals. It is a product of a society in crisis.

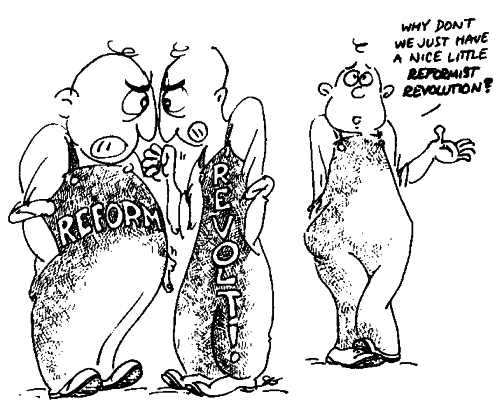

People do not go to bed one night as reformists and wake up the next day as revolutionary socialists. As people move between two radically different views of the world, they often stop off at halfway positions, holding a variety of confused or inconsistent views. Of course, certain centrist leaders will seek to exploit such confusions and inconsistencies in their own political interests. But the vast bulk of those who make up centrist organisations or currents are a vital part of our audience – it is our job not so much to denounce their inconsistencies as to try to clarify them.

The problem of centrism in the socialist movement first became of vital importance in the First World War. The war drove a deep wedge between those who put loyalty to their own nation first, and those who continued to argue for proletarian internationalism.

But among the opponents of the war two camps soon emerged. On the one hand were those like Karl Kautsky, whose knowledge of the Marxist classics was so great that before the war he had been known as the ‘Pope of Marxism’. He now argued that what was needed was to end the war by negotiation, so that the old International, including pro-war and anti-war elements, could be cobbled together again.

The other camp, including Lenin, argued that there could be no turning back. The war had shown a fundamental divide between those who wanted to smash the bourgeois state and those who didn’t. So Lenin called, not for peace negotiations, but for turning the war into revolution. In this three-way line-up, Kautsky and friends came to be known as ‘the Centre’. In the period immediately after the war, when millions of workers were determined that a similar catastrophe should never occur again, the ranks of the centrist organisations grew rapidly. Towards the end of the war Kautsky and others were expelled from the German Social Democratic Party and formed the USPD (Independent Social Democratic Party). By 1920 the new party had 800,000 members, as against 50,000 in the German Communist Party.

This caused deep problems for the international revolutionary left, united in the newly founded Communist International.

The Russian Revolution was extremely popular with workers all through Europe, and many of the old-time politicians who had thoroughly disgraced themselves during the war were trying to climb back into favour by jumping on the pro-Russian bandwagon. The Communist International had to take a very tough line towards the centrists, especially the centrist leaders – otherwise the new revolutionary International would have been taken over by parasites and has-beens.

The International drew up a set of twenty-one tough conditions designed to keep out centrists. As the president of the International, Zinoviev, put it:

‘Just as it is not easy for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle, so, I hope, it will not be easy for the adherents of the centre to slip through the 21 conditions.’

Centrism grew very rapidly – only to fall apart just as rapidly. In October 1920 the USPD debated its attitude to the Communist International. After hearing a four-hour speech from Zinoviev delegates voted to join it; 300,000 members did so and merged with the revolutionary Communist Patty. Within three years the remaining rump of the ‘centre’ round Kautsky collapsed back into the Social Democratic Party.

In subsequent revolutionary crises the role of centrism has been similar.

At the beginning of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 the POUM was a serious contender for the leadership of the Spanish working class. It had significant working class support and a leadership with a creditable revolutionary anti-Stalinist past.

Yet the inconsistent politics of the POUM led to disaster. It failed to make a head-on challenge to the influence of reformists and anarchists in the trade unions and in the army. It stood for a government composed exclusively of representatives of working class organisations – but when the other left parties rejected this view it entered a coalition with bourgeois representatives. The POUM opposed reformism but failed to fight it. And as a result it cut its own throat – and left the Spanish workers to face a defeat that would last a generation.

In more recent times the experience has been pathetic rather than tragic.

In 1960 the French PSU (United Socialist Party) was founded by members of the Socialist Party disgusted with their leaders’ support for the Algerian war and capitulation to Gaullism. In its early years it took some principled and courageous initiatives in favour of Algerian independence. But the party consisted of a bunch of quite divergent political groupings and used the excuse of ‘internal democracy’ to avoid a clear decision between them.

Its relations with the leaders of the CFDT trade union meant that it never organised its trade union militants on a fractional basis. In the general strike of May 1968 many PSU militants played a key role; but the party as a whole had no impact because it could not make up its mind whether it was developing the embryos of workers’ power in the factories or organising a come-back for former prime minister Mendes-France.

In the early seventies, when the Socialist Party started to rebuild on a new basis, a large part of the PSU went over; a former PSU leader, Michel Rocard, now heads the most right-wing tendency in the French Socialist Party. The PSU lingers on, as a kind of ‘Beyond-The-Fragments’ rump, unable to make up its mind whether to campaign against the Mitterrand government’s sell-outs or to negotiate to join it.

Just because centrism is a half-way house, any centrist party or current will Contain a variety of groups moving in different ways; some moving from revolution to reformism, some from reformism to revolution – and some staying where they are because they prefer to fish in muddy waters.

So, relating to centrists requires a certain amount of subtlety. Blanket denunciations are easy, but winning those who are moving the right way, needs a bit more skill. We can’t all recruit three hundred thousand new members in four hours, like Zinoviev, but we can try.

Above all, the question of centrism varies according to the ups and downs of the class struggle. When masses of workers are moving to the left, then centrism presents enormous dangers. For if centrists take the lead of the movement, they will fudge the issues and deflect it front the path it should follow. But if the masses are moving to the right, then the task is to attract those few centrists willing to swim against the stream.

In 1920 the Communist International put up the barriers against centrists who found it fashionable. But by July 1921 Lenin was criticising ‘exaggeration’ in the fight against centrism.

In today’s situation there is little danger of the SWP being swamped by a flood of centrists seeking to join us. We have to meet, debate and work with centrists as part of the process of building an organisation. But at the same time’ total clarity about centrism is necessary.

A study of history, from Kautsky to Rocard, and an insistence on the basic principles of Marxism, are necessary to forestall the danger that when a revolutionary upsurge comes, the centrists will make the running. And for that we need a party with a clear programme and a trained cadre. Just the sort of Leninist dogmatism any self-respecting centrist would have nothing to do with.

Ian Birchall Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 15 May 2010