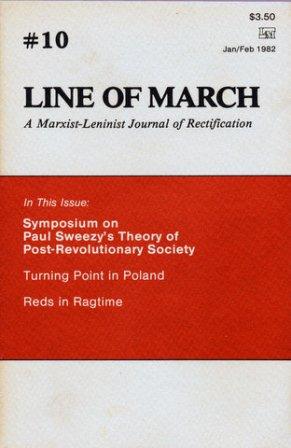

First Published: Line of March, No. 10, January/February 1982.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The Polish communist party has crossed its Rubicon. . .the fate of Polish socialism and the dictatorship of the proletariat hang in the balance. The international lines of the class struggle have been drawn sharply and there is no longer any middle ground. The line-up contains few surprises; the adversaries face off grouped either behind the Polish party and government or behind Solidarity.

Recent events in Poland have come as no surprise to serious political observers across the spectrum from left to right. In the weeks immediately preceding the declaration of a state of emergency by a special military council supported by the Polish United Workers’ Party (PUWP), the political contradiction between Solidarity and the government had intensely accelerated. For months there had been a situation of growing dual power–a situation which had virtually paralyzed Poland’s economic, social, and political life. Increasingly it became clear that the political crisis would be resolved only when one of the two main political forces, either Solidarity or the PUWP, forcefully asserted its authority over the other.

Then, after months of agonizing hesitation, the Polish government finally took decisive measures in early December, 1981, to do what had clearly become inevitable: smash the political power of Solidarity.

All efforts to mediate the crisis through negotiation between Solidarity and the government had failed–indeed they had to, since a negotiated settlement acceptable to both parties was impossible. Solidarity’s proposal for a system of “shared power” between itself, the Catholic Church, and the PUWP was nothing but a demand for the PUWP’s political surrender. Likewise, the government’s proposal, that Solidarity be accorded a recognized status at the trade union level and that its representatives cooperate in a joint effort to resolve the Polish crisis under the leadership of the PUWP, ran counter to the political aims of Solidarity’s leadership, who would have seen agreement as a surrender of the de facto power which they had already achieved.

The reason for this impasse is obvious. On all the fundamental questions of Polish life, the leadership of Solidarity and the PUWP are at odds with each other. While Solidarity’s strength in the Polish working class has been based in its role as “champion” of the workers around immediate economic issues, the perspective of its leadership has been profoundly political from the very beginning of the confrontation. Sometimes stated openly, but more often masked, the goal of Solidarity’s leadership has been to fundamentally restructure Polish society politically and economically, a process which all leading political forces in Solidarity acknowledged would have to take the form of a consciously organized “revolutionary” upheaval.

This perspective has been most explicitly articulated by the leadership of the Committee for Self Defense (KOR). Since, as the Wall Street Journal has aptly noted, ”many of Solidarity’s key advisers come from KOR ranks and much of the union’s basic ideology and organization originated in KOR”[1] any estimate of Solidarity’s actual political goals must give appropriate consideration to the perspective of the KOR leadership.

A sympathetic commentator, writing in the Monthly Review, summed up that KOR perspective as follows: “The existing form of society in Poland constituted a new type of class domination in which a ’central political bureaucracy’ exercised exclusive control over the means of production and the disposal of the surplus product Such a system could be overthrown only by revolution and the establishment of direct democracy with a system of workers’ councils and a central council of elected delegates.” [2]

Hardly anyone doubts that the fundamental orientation and direction of Solidarity, either spontaneously or consciously, would bring it to mount a challenge for state power. This is precisely why Solidarity’s most enthusiastic supporters–whether in the central councils of U.S. imperialism or in the ranks of the left–have rallied around its banner, while espousing differing ideas on the exact nature of the restructuring, all agreed on the need for fundamental restructuring.

The PUWP, on the other hand, while explicitly self-critical and willing to make numerous concessions to Solidarity and the Catholic Church in terms of their participation in the organization of Polish life, has been obliged to defend the fundamental elements of the present social arrangement in Poland. Supporters of the Polish government, whatever their differing degrees of criticism of the errors of the Polish party, are united in the recognition that the fundamental property relations in Poland are socialist, that they are seriously threatened, and that they deserve to be defended.

In these circumstances, a confrontation was inevitable. In the weeks before the declaration of martial law, both sides inexorably pursued the logic of their positions and moved toward a showdown. Immediate strikes called or abetted by Solidarity over every major and minor dispute in the country put the Polish economy on the verge of collapse. The PUWP proposed legislation banning strikes until all other avenues for the resolution of disputes had been exhausted. Solidarity, sensing that such a move would deprive it of its main instrument of power, called for a general strike in the likely event that such legislation passed the Polish parliament.

The Solidarity leadership apparently well understood that Poland had reached a historic crossroads. On December 7, the Polish government released tape recordings of a secret meeting of the Solidarity leadership.[2a] Confirmed as accurate by Solidarity itself, these left little doubt as to the intentions of the union. “The confrontation is unavoidable,” Lech Walesa said on the tapes, “and the confrontation will take place. We have to awaken people to that. I wanted to reach the confrontation in a natural way, when almost all social groups were with us. But I made a mistake because I thought we would keep it up longer and then we would overthrow those parliaments and councils and so on.” Walesa went on to declare that the union should not say these things “aloud” but rather should say “we love you, we love socialism and the party and, of course, the Soviet Union, and by the accomplished facts we should do our work and wait.” [3]

Others in the Solidarity leadership were even less restrained than Walesa. Zbigniew Bujak, head of the Solidarity branch in Warsaw, is recorded declaring that “The government should be finally overthrown, unmasked and deprived of credibility.” Solidarity leaders in other parts of the country were voicing similar sentiments. From all appearances, the general strike would be the condition for Solidarity to make its move for seizure of the government.

It was in this setting that the Jaruzelski government made its move, utilizing military force to arrest the leaders of Solidarity and to break up the strike movement The Polish party (or some sections of it) had obviously preplanned this move carefully, tactically waiting for a sufficient provocation as a pretext to implement it Solidarity’s leadership provided the provocation, and the Polish military and party executed the plan fairly smoothly.

The confrontation is filled with all the anomalies which have characterized the Polish crisis from the beginning. Solidarity first emerged as a political force built on the anger of the Polish working class–much of it justified–at the consequences of the disastrous policies pursued by the PUWP. But, as we shall attempt to demonstrate, the program and objectives of Solidarity, in the name of correcting abuses of the past years, would have actually undermined the socialist foundations of Poland and, therefore, the real interests of the Polish working class. The PUWP, however, is clearly responsible for an economic policy which has instituted grave and totally unnecessary distortions into Polish socialism. At the same time, the present PUWP leadership quite correctly (in our opinion) has refused to concede that the system of socialism itself is at fault. Ironically, the party, for all its weaknesses and relative isolation from the mass of Polish workers, has emerged as the main political force in Poland trying to defend socialism and the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Only those who have worked their way through this maze of contradictory surface phenomena have the basis for arriving at a serious objective understanding of the real politics of the Polish crisis. Those who have not (or will not) do so are either dilettantes or still politically motivated principally by scattered prejudices and confusion. Yet even clarity on the forces and stakes internal to Polish society does not exhaust the full significance of what is involved in the Polish crisis.

The Polish crisis must, of necessity, be placed in an international context. In our opinion the stakes involved can be crystallized in two clear-cut questions: Would a Poland in which Solidarity held power remain part of the socialist camp? Would Poland under Solidarity remain part of the world front against imperialism?

We believe that the answer to both these questions is “no.”

Of course, Walesa and other Solidarity leaders have publicly argued that they would not attempt to pull Poland out of the Warsaw Pact or the Eastern European Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA). But it is hard to have confidence in such statements. First, all the leaders of Solidarity obviously have been prepared to say whatever they deem necessary in public while biding their time with their real intentions. Even more telling, however, is that the internal logic of the Solidarity program would inevitably weaken socialist relations of production in favor of a market economy and lead to a rupture with the Soviet Union and the other socialist countries of Eastern Europe, a process which could only lead to a strengthening of Poland’s economic ties to the imperialist countries. And, from a military point of view, such a development would gravely jeopardize the military security of the socialist countries. In fact, the continued functioning of the Warsaw Pact becomes inconceivable if the Polish representatives are the political leaders of Solidarity with all their manifest ties to the Catholic Church and other agents of imperialism.[3a]

The likely policies of a Poland under Solidarity’s leadership on political, economic, and military support for national liberation struggles against U.S. imperialism leave little room for illusions. Would a Solidarity-led Poland allocate a portion of its industrial production to aid Nicaragua or the struggle in Namibia? Unlikely. Where would a Walesa government stand as the complexities of the international class struggle tested the unity of the anti-imperialist forces? In fact, Walesa, whose top political adviser is none other than the Pope, offers us a rare insight into his pledge to defend socialism in Poland when, as Newsweek has noted, “he has cited Japan as a model of the sort of economic development that he believes is possible in Poland.” [4]

Granted, the PUWP itself has not been a paragon of internationalism; nevertheless, it can be, and has been, held accountable to the concrete politics of proletarian internationalism. For all the hesitations and vacillations of the PUWP, Poland under its leadership has never made common political cause with imperialism. It would, however, take a thoroughly unwarranted confidence in Solidarity’s political leadership to believe that a Poland under its rule–in alliance with the Catholic Church and with political and financial backing from the West–would long remain in a front against imperialism.

We would argue that the interests of socialism, both internationally and internal to Poland, and of maintaining the united front against imperialist assaults and maneuverings require a stand in opposition to the Polish Solidarity movement as it is presently constituted and led– and a stand in support of the Polish government and party.

Ironically, both the international bourgeoisie (and its host of reactionary ideological and political servants) and the international communist movement actually agree on where the battle lines are drawn and on the stakes involved in the Polish crisis. Zealous Polish-Americans, the AFL-CIO officialdom, the Pope, and Ronald Reagan acknowledge that Solidarity is up against the “forces of communism.” All their actions, from U.S. economic sanctions against the USSR and Poland to the Christmas candle vigil, are expressions of support for the trend of moving Poland toward “Western-style democracy.” Their political posture toward the communists and their supporters is, if nothing else, refreshingly straightforward–“we want different things, so we’re on different sides; the best social system will win out in the end!”

Consequently, the raging controversies over the nature of the Polish crisis are not with the right, but rather on the left. For more than a year U. S. imperialism has made a cause celebre of Solidarity; it has become, without exaggeration, the central feature of the anticommunist ideological campaign accompanying the imperialist military build-up. Disarmed by their own prejudices, many on the U.S. left have found themselves in lockstep with the labor lieutenants of capitalism and their own bourgeoisie on the question of Poland.

There are numerous convoluted and belabored explanations to justify this obvious political predicament–the jealously held belief that although they march alongside reactionaries of all stripes, they march to a different drummer, with a different set of slogans, etc. But facts are stubborn things. Support in the U.S. for Solidarity is an ideological assault on socialism; the leading banner is anticommunism; and to march at all one must march beneath that banner. Whatever the subjective intentions of this assortment of leftists, they are doomed to be overshadowed and swept along in this “movement,” and to be looked upon as little more than political curiosities. As a result such leftists are qualitatively compromised and in no position to explain to the U.S. working class the real underlying objectives of U.S. imperialism in the present Polish crisis.

Of course, within the safe confines of left circles this political position can gain a much greater hearing than in the rough-and-tumble of the “mass” pro-Solidarity movement Here the political argument goes something like this: Imperialism would like to make Solidarity serve its interests, but it has miscalculated, not realizing that “real” workers’ power in Poland will actually harm the interests of imperialism. By the same token, the PUWP is not defending “genuine” socialism but only “Soviet socialism.”

Such an argument, admittedly simplified, merely reveals that those who advance it have not yet learned to think politically, but are still content to indulge in wishful thinking. They behave as though a political movement can be characterized simply by its self-proclamations or by the numbers of workers who follow it. They also fool themselves into thinking that they can dismiss the urgent question of the defense of socialism in Poland merely by labelling it “Soviet socialism.” But a political movement can only be assessed by the actual role it plays in the world, not by its intentions or proclamations. This simple fact, which has been so readily grasped by the international bourgeoisie, seems to have eluded much of the left, which refuses to face the unpleasant realities that the enthusiasm of the agents of imperialism for Solidarity implies.

Similarly, since “Soviet socialism” is the only type of socialism that actually exists in real life in the USSR and Eastern Europe, any attempt to diminish the significance of its defense– at a time when the fundamental precepts of the socialist system and the actual institutions of state power are being challenged–is nothing but a thin political smokescreen to hide vacillation in the face of imperialism. This constitutes class collaboration no matter how much such surrender is masked by a thoroughly unfounded optimism in the capacity of Solidarity to build a “new and improved” type of socialist system.

Not surprisingly, the major ideologically motivated currents spreading political confusion on the left concerning Poland are the Trotskyist and social democratic trends. The present Poland controversy is only the specific form of the ongoing polemic and struggle between Marxism-Leninism and those established opportunist currents within the socialist movement By now it should come as no surprise to communists to find Trotskyists and social democrats of all stripes on the other side of the barricades, attempting to provide a ”left” cover for imperialism in the name of “genuine” or “democratic” socialism. However, of more immediate concern is the fact that a number of forces in and around the Marxist-Leninist movement have also taken centrist and opportunist positions on the Polish crisis. It is to this quarter that we principally direct our polemic.

How will we proceed?

In the next section (II) we will review and deepen the basic analysis we made more than a year ago on the fundamental causes of the Polish crisis. Here we attempt two things: first, to develop an assessment of the objective roots of the troubled post-World War II history of Eastern Europe, which has experienced major confrontations, with clear anti-socialist implications, in Hungary (1956), Czechoslovakia (1968), and Poland (1970 and 1980); second, to extend our analysis of what we hold to be the principal subjective cause of the Polish crisis, the revisionist general line of the PUWP since 1956.

In Section III we offer a concrete analysis of the politics of Solidarity as they have been revealed in the developing crisis in Poland over the past year and a half. Our point here is that the anti-socialist direction of Solidarity can be demonstrated through an analysis of its actual programmatic goals and of the actual political forces who comprise the majority of its leadership.

Finally, in Section IV, we take up some consideration of what the resolution of the Polish crisis might involve, and we try to locate this concern in the broader historical process of the intersection of socialist construction and proletarian revolution.

The root cause of the present crisis in Poland rests in the incorrect general line of the PUWP which has guided the practice of the Polish communists for the past 25 years. The net result of implementing that opportunist line has been the inability to consolidate socialism and the proletarian dictatorship in Poland. Vacillation, hesitation, and a nationalistic and pragmatic outlook on the process of socialist construction have long characterized Poland’s communist party and resulted in widespread corruption and abuse of power within the communist ranks. Together with negative concessions to non-proletarian forces, this has created conditions for a political challenge to proletarian power to take root in Polish society and grow to the point that the danger of capitalist restoration has become real, concrete, and impending.

This is not to deny that Poland, along with the other Eastern European countries, faced certain objective difficulties flowing from its particular history and the efforts by imperialism to undermine the socialist camp. Any analysis which does not take these objective historical factors into account is bound to be subjective and one-sided. Nevertheless, we hold the view that the opportunist response of the PUWP to these objective difficulties–and not simply the objective conditions themselves–set in motion the gravest challenge to proletarian power in Eastern Europe since the end of World War II.

Capitalism developed unevenly in Europe, taking root first in certain Western European countries (England, France, Holland) and, in time, encompassing the rest of the continent. This uneven development had a profound effect on the relations between the capitalist powers and on the historically specific tasks of both bourgeois and proletarian revolutionary forces in the various countries of Europe.

As a result, the economic and political history of Eastern Europe is significantly different from that of the Western European countries. Politically, Eastern Europe was characterized by the existence of multinational states: Russia, Germany, the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires between them incorporated the vast majority of the peoples and nations of the region. The strivings of the bourgeoisies of these oppressed nations gave rise to movements for national independence and an accompanying nationalist ideology which have played a powerful role in shaping both the politics and culture of much of Eastern Europe. In certain countries–Poland and Hungary in particular, where Catholicism remained the dominant religion–the church grew to be an institution that expressed not only the religious sentiments of the masses but their nationalist aspirations as well.

Economically, Eastern Europe lagged in industrialization so that significant feudal remnants in agriculture persisted well into the twentieth century. A reactionary landlord class thus exercised substantial political power and influence compared to Western Europe. Likewise, the peasantry remained a numerically larger class than the proletariat in most Eastern European countries right up through World War II.

These historical particularities of Eastern Europe clearly have shaped the actual social conditions and ideological currents confronting the communists in this region in the post-World War II period. To this history we must add the particular international circumstances under which the tasks of socialist construction were undertaken in Eastern Europe.

After Eastern Europe was liberated from Nazi rule in World War II, the questions which had to be answered concretely in each country were which political forces would rule and what would be the fundamental property relations. The form that developed–People’s Democracy– was an attempt to speak to the historically concrete conditions of proletarian power in Eastern Europe under circumstances framed by the pressing necessity to reinforce and extend the political and military security of the Soviet Union. The first chilling intimations of the Cold War against socialism followed quickly on the heels of the Nazi surrender, a situation rendered all the more formidable by the U.S. possession of the atomic bomb and its bellicose posture of nuclear blackmail.

Initially, the governments of the People’s Democracies were viewed as popular fronts of genuine anti-fascist forces under the leadership of reconstituted workers’ parties which were usually formed by mergers of communist and social democratic parties. (In Poland, the leadership of the Catholic resistance refused to participate in the popular front government on the ground that as the dominant political force in the country, the church would not subordinate itself to a communist-dominated government. This further aggravated for Poland what was generally a relatively unstable and delicate class alliance in the region.)

Economically, the People’s Democracies were explicitly oriented toward socialism but not yet socialist. Since the largest landlords and capitalists had invariably collaborated with the Nazis, there was little political problem in expropriating their property. The huge landed estates were broken up and distributed among the peasantry. Major enterprises and banks were nationalized; however, sizeable sectors of industry and commerce remained in private hands. Since significant sections of the bourgeoisie and petit bourgeoisie had participated in the anti-fascist struggle, it would have been a political error to expropriate them and thus narrow the base of the revolution. The prospect at that time was a gradual step-by-step evolution of the economy toward socialism, a process deemed possible by the fact that the fundamental question of political power had in the main been settled–the proletariat already held power both as the leading force in the popular fronts and through the internationalism and military might of the Soviet Union.

By 1948, however, it had become clear that the political and economic realities of the international class struggle would not permit a relatively pacific and protracted process of socialist transformation in Eastern Europe. Winston Churchill’s infamous 1946 “Iron Curtain” speech had virtually called for a concerted military effort to “liberate” Eastern Europe, on behalf of Western capital and roll back the boundaries of socialism to the Soviet Union. Reactionary centers in the U. S. spoke openly of the virtues of using U. S. military supremacy to accomplish this objective through the integrated command of NATO. In addition, to the east, the imminent victory of the Chinese Revolution further fueled imperialist anxieties. The danger of a Western military strike against Eastern Europe, with the Soviet Union held in check by nuclear blackmail, was quite real.

Fortunately for the international proletariat–and, indeed, for all humanity–the Soviet Union was able to produce its own atomic weaponry. (Just how remarkable an achievement this was in light of the extensive destruction of the Soviet industrial plant during World War II is still not fully appreciated within the U.S. movement) The threat of Soviet atomic retaliation in Western Europe was sufficient to dampen the ardor of all but the most reckless sectors of U. S. finance capital. Nevertheless the danger was hardly over. The imperialist strategy of “cold war” intensified. As a result, the working class in Eastern Europe had to brace itself for a massive campaign of subversion, sabotage, and ideological assault (short of outright military invasion) aimed at destabilizing and reversing the socialist gains.

These were some of the circumstances which led the communists in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe to effect a major refinement in their strategic conception of how socialism would be built The imperialist threat required a much more systematic and elaborate coordination–not just of military matters, but economic and political policies as well–between the People’s Democracies and the Soviet Union. As a result, the timetable for the gradual evolution from People’s Democracy to socialism had to be accelerated.

The failure to step up the tempo of socialist construction could have had serious negative consequences during the Cold War. Tendencies toward capitalism inherent in a sizeable bourgeois class and in widespread petty commodity production (especially in agriculture) would have provided the imperialists with a receptive class base for its ideological, political, and economic offensive. Systems of political pluralism based solely on the anti-fascist past would have maintained at the centers of political power bourgeois forces whose basic ideological allegiance with capitalism could seriously destabilize the regimes in a period of intensified class struggle between the two social systems. Consequently the process of socialist construction and integration of Eastern Europe into a socialist camp was accelerated. Major steps toward the collectivization of agriculture were taken in all the Eastern European countries. Measures to restrict more drastically the private sector of the economy were proposed and enacted. The popular front political alliances were subject to the pressures of a stepped-up program for socialist transformation. The Communist Information Bureau (Cominform) was founded, and shortly thereafter an integrated system of economic and military cooperation between the Soviet Union and the East European countries was established.

Noteworthy among the opponents of the new program were Tito in Yugoslavia and Wladyslaw Gomulka in Poland. The case of Yugoslavia offers us at least a partial glimpse at what might have happened in the rest of Eastern Europe had the timely adjustment in the line on People’s Democracy not been made. First, Yugoslav “socialism” is, to say the least, a highly dubious proposition. The Yugoslav working class is subject to all the uncertainties of capitalism: high unemployment, migrant labor, inflation, cyclical crisis. The Yugoslav economy remains tied to the vicissitudes of the market (especially the world market) rather than to scientific planning motivated by social need. Second, the role of Yugoslavia in the struggle against imperialism and in support of national liberation and proletarian revolution is, at best, vacillating, occasional, and incidental. In fact, it is frequently conciliatory and even sometimes outright collaborationist.

Gomulka was not able to do in Poland what Tito had done in Yugoslavia, but not for want of trying. As early as 1948 he was advancing his line on the ”Polish road to socialism” which, in effect, meant remaining tied to the politics and social arrangement of the People’s Democracy period, including the legitimization of the political and ideological role of the Catholic Church and only token steps toward collectivization of agriculture. However he was isolated and temporarily purged from the Polish party, apparently through considerable Soviet pressure.

With the exception of Yugoslavia, then, the new political line on socialist construction was implemented in Eastern Europe. Closer economic coordination between the Eastern European countries and the Soviet Union was established and the joint military defense of the region was undertaken by the Warsaw Pact Given the surrounding circumstances, we believe that this was a correct line essential for the defense of proletarian power in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

Nevertheless a political price was paid for this necessary adjustment In several countries–Hungary and Poland especially–the ideological transformation of the masses was far from complete. The reactionary political influence of the Catholic Church was still quite strong and was reinforced by those bourgeois class forces who rightly saw the accelerated program of socialist construction as a form of class struggle directed against them. Even within the working class itself (with large numbers of people maintaining ongoing family ties to the countryside and only one step out of the peasantry themselves) there was ideological resistance to accelerated socialist transformation. In addition to these objective difficulties, the parties made numerous errors, some of which were provoked by capitalist agents, others not However, every error– whether historically avoidable or not–was quickly seized upon by reactionary class forces and utilized to fuel mass resistance to the new line.

It is this complex set of historical contradictions which has framed the periodic rebellions, strikes, and oppositionist political actions which have errupted at one time or another in almost every Eastern European country in the course of consolidating socialism. Despite these difficulties and shortcomings, the fundamental socialist transformation has been successfully accomplished. The attempts by imperialism to dismantle proletarian power in Eastern Europe have failed. The aggressive imperialist policy of “rollback” soon gave way to the more passive policy of “containment.” By 1956, the imperialist powers had signalled the de facto recognition of the existing borders and political realities of central and Eastern Europe.

In the case of Poland, the gains were dramatic. By 1953 the Polish economy had almost quadrupled its prewar level. Poland became the tenth most industrialized country in the world. Most industry had achieved a high level of socialization of the work process. Centralized planning of industrial production and distribution had been introduced. The working class enjoyed absolute job security, a wage level far above its prewar income, and an extensive social wage in the form of a broad system of free health care, education, old age protection, etc.

Nevertheless there were numerous unresolved contradictions in Polish society which would become pitfalls in Poland’s path toward socialism. To begin with, the petit bourgeois social base was substantial, aggravated by the fact that a relatively small degree of collectivization of agriculture had been achieved. The Catholic Church, which had always functioned in a thoroughly conscious and manipulative fashion, remained a powerful influential political force, particularly in the countryside. Polish nationalism (with its particular antagonism toward Russia) remained a potent bourgeois ideological force which readily lent itself to anti-Sovietism. And, most importantly, the PUWP itself was quite weak ideologically, never fully succeeding in consolidating a firm Marxist-Leninist foundation and leadership core for the party.

It was in this somewhat contradictory and complex reality of Poland that the situation went from bad to worse in the wake of the anti-Stalin campaign of the late ’50s. Khrushchev’s revisionist formulations concerning a new, peaceful strategy for completing the world revolution went hand in hand with an attempted Soviet rapprochement with Yugoslavia and Tito. The confusion this stirred up contributed to a major upheaval within the PUWP resulting in the consolidation of a nationalist deviation in the Polish party–symbolized by Gomulka’s dramatic re-entry into the party and emergence as its head. From this point on a qualitatively new general line on socialist construction was to shape the policies of the PUWP over the next quarter of a century.

To highlight fully the significant revisionist turn taken by the PUWP in 1956 we utilize Lenin’s framework on the three main sources of the threat of capitalist restoration after the proletariat has succeeded in taking state power. Lenin notes that these are: the ousted bourgeoisie, the power of petty commodity production, and international capital. By the same token, the consolidation of socialism is completely bound up with the proletariat’s success in vanquishing capitalism on all three of these fronts. When Lenin speaks of the intensification of the class struggle under socialism and, therefore, the centrality of the dictatorship of the proletariat, he is referring precisely to these struggles.

The ousted bourgeoisie cannot help but dream and scheme of their return to power and property. In the very moment of their defeat they are a hundred times more bitter and determined than ever before. And they still retain a significant social base among the masses, for there are always bound to be sectors which never completely unite behind the revolution. In particular, the bourgeoisie’s social base is most likely to be found among those who themselves were in close proximity to power and property previously; their influence is stubborn and far exceeds their numbers. By virtue of both wealth and experience in the uses of power the bourgeois elements are capable of turning every contradiction and shortcoming of the new society into support of their own revival.

Petty commodity production is an even more stubborn force obstructing socialist transformation and fostering the restoration of capitalism. Unlike the ousted bourgeoisie, who can (and must be) physically and politically suppresed, petty commodity production cannot be eliminated through suppression. It must be replaced by large-scale, socialized production through the step-by-step development of the forces of production. In the meantime petty commodity production, by its very nature, remains the breeding ground of capitalism, generating capitalist relations in both production and trade as well as bourgeois individualism and ideology.

But even when these two sources for the restoration of capitalism have been substantially overcome, socialism cannot let down its guard and rest content. Its social system cannot be completely consolidated until the capitalist system has been defeated on a world scale. This is not essentially a military question. The continuing threat of imperialist military assault on socialism is only the most concentrated expression of the insurmountable and antagonistic economic, political, and ideological contradictions between the two opposing social systems. Socialism cannot be deemed secure anywhere until this last contradiction is resolved, a point which Stalin underscored in noting the distinction between building socialism in one country and “the final [worldwide] victory of socialism [as] the full guarantee against attempts at intervention and hence against restoration.”[5]

The success of the proletariat in resolving these three struggles does not, of course, exhaust the tasks of socialist construction (whose laws must be grasped in their own right). But these particular tasks do capture the function of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the essence of the class struggle under socialism. Therefore, the way in which a party holding power takes up these particular tasks offers a good measure of whether that party is pursuing a proletarian line or an opportunist line in socialist construction.

On all three counts, the general line guiding the PUWP ever since 1956 must be judged thoroughly opportunist and revisionist. In each of these three areas, the PUWP has made incredible, negative concessions to non-proletarian classes and to their political representatives. These negative concessions, aside from weakening the socialist system in Poland, are the direct source of the present economic and political crisis.

On the surface it would appear that the old bourgeoisie has been completely ousted from Polish society. There are no capitalists worthy of the name in Poland today. The former owners of industry and the banks have lost their property and in this narrow, economic sense do not exist or function as a class. They nevertheless continue to exist as real people, as do their immediate families, offspring, and business retainers. They are also more than scattered individuals. Ties of tradition, ideology and former (but vividly remembered) status continue to hold them together.

Such a situation is normal and historically unavoidable in any socialist country. Any attempt to physically exterminate every member and retainer of the old ruling class is bound to have disastrous consequences for proletarian power since it would deny the proletariat access to much-needed skills and experience in economic management and would inevitably alienate large numbers of the non-party masses. The physical existence of large numbers of ousted bourgeois elements (and their continued international contacts) must therefore be seen as a reality of socialist society, especially in its early stages.

But what does not have to be accepted–indeed, must not be accepted–in socialist society is the reinforcement of the political institutions of the ousted bourgeoisie. This is a point which all the proponents of a “pluralist” political system under socialism are totally unable to comprehend. In Poland, this was precisely the area in which the PUWP made negative concessions to the ousted bourgeoisie. The form of these concessions was not in permitting a multiplicity of political parties, but rather in the legitimization and reinforcement of the main ideological and political force in Polish life which actually continued to represent the ousted bourgeoisie–the Catholic Church.

Historically, this is the role that has always been assumed by the church in Poland. The identification of the Catholic Church with Polish nationalism signified the fact that the aspirations of the nationally oppressed Polish bourgeoisie found their ideological reflection in the church’s defense of Catholicism against the dominant non-Catholic religions of the empires among which Poland was divided. The Catholic Church in Poland has always functioned as a political institution. During and after World War II, the contention between the Catholic-led government-in-exile in London and the communist-led government-in-exile in Lublin was the concentrated expression in the political realm of the underlying contention between capital and labor which would immediately confront postwar Poland.

Precisely because of the Catholic Church’s identification with Poland’s historic struggle for independence and its active role in the antifascist resistance, it could not be arbitrarily removed from the political and ideological life of Polish society. This presented a delicate contradiction that could only be resolved over a relatively long period of careful ideological education and remolding among the masses. The best the PUWP could do in the period prior to 1956 was to attempt to circumscribe and neutralize as much as possible the church’s role in secular society. It also had to recognize that so long as Polish agriculture was dominated by small-scale commodity production, the sizeable Polish peasantry would continue to provide the Catholic Church with a significant and viable social base.

A central feature of the opportunist line adopted by the PUWP in 1956 was a major adjustment in the party’s policy toward the Catholic Church. Recognizing the church’s continued influence among the masses, especially in the countryside, the party decided to enlist the church as a “junior partner” in its management of society. Political concessions to the church hierarchy were seen as a means of placating those sections of the masses who still looked to the church as their ideological divining rod. As a result, the role of the church in Polish society was qualitatively expanded. The government provided financial support through salaries for priests and funds for church construction. Church-run schools from kindergarten to the university level were not only permitted but supported by the workers’ state. A whole Catholic intellectual life expressed through daily newspapers, journals, and cultural institutions flourished from 1956 until today. In short, Catholicism remained the “unofficial state religion” and the goal of winning the masses to science and atheism was effectively surrendered.

Undoubtedly the pragmatist orientation of the PUWP leadership explained and justified this terrible arrangement. The party retained effective control over the economy and the state. In exchange, the church was given free rein in the realm of ideology. For the Catholic Church in Poland, besieged and suppressed for centuries, this was an offer too good to refuse, for it has never underestimated the power of ideology. Naturally, as the church extended its ideological influence among the masses, the price it exacted from the communists for promoting social peace and cooperation continued to go up. By the time the latest crisis unfolded, the Catholic Church had matured into a sophisticated political organization and was well-positioned to begin to operate in a more explicitly counter-revolutionary fashion which it quickly commenced to do through the personages of Lech Walesa and other leading figures in Solidarity. Meanwhile the international bourgeoise knows full well that the existence of a Polish Pope is viewed in Poland as the highest and most significant national achievement in the long history of the Polish nation–a sobering and paradoxical expression of intense bourgeois nationalism in a socialist country and in the era of proletarian internationalism. Indeed, the Catholic Church in Poland has thrived under the opportunist benevolence of the PUWP!

While we live in a small-peasant country, there is a firmer economic basis for capitalism in Russia than for communism. ... Anyone who has carefully observed life in the countryside, as compared with life in the cities, knows that we have not torn up the roots of capitalism and have not undermined the foundation, the basis, of the internal enemy. The latter depends on small-scale production, and there is only one way of undermining it, namely, to place the economy of the country, including agriculture, on a new technical basis, that of modern large-scale production.[6]

This observation of Lenin made shortly after the Bolshevik Revolution has a universal significance for the tasks of socialist construction in agriculture. The failure to grasp this truth is, in our view, at the heart of the Polish crisis.

The main political difficulty bound up with the peasant question in the context of the proletarian revolution is that the main thrust of the class struggle in the countryside could be more precisely defined in a number of countries as the struggle against feudalism (or at least powerful feudal remnants) rather than as the struggle against capitalism. In such countries, the demand of the peasants who (given their numbers, etc.,) had to be enlisted as allies of the proletariat, was not for socialism but for land. The realization of this demand, however, implies the proliferation of small, private plots and small-scale production. It also inevitably leads to a drop in the production of agricultural commodities since the peasants, now having their own plots, using relatively primitive methods on a narrowly circumscribed land base, directly consume a larger portion of their production than previously. In short, it results in a primitive form of capitalist commodity production.

The harnessing of agriculture to a socialist economy cannot proceed under such conditions no matter what country it is; although the process and the tempo of the transformation from a private to a collective economy in agriculture is first and foremost a political question, extremely diverse from one country to another.

The problem confronting most of the Eastern European countries, especially Poland, was that, on the one hand, the full flowering of socialist construction required the elimination of a peasant-based, small-scale agriculture and its replacement by large-scale production based on state and collective farms. On the other hand, most peasants in Poland were far from enthusiastic about the prospects for collectivization. The Polish peasants were further reinforced in this outlook by the Catholic Church which saw in the transformation of the peasantry the erosion of its own social base.

As a result, the process and tempo of the changeover from private to collective agriculture had to proceed with considerable delicacy requiring a deft combination of ideological work by the party and step-by-step practical experience demonstrating that the majority of peasants as individuals (not as a class) would be far better off under socialist relations in agriculture.

Prior to 1956, this was the policy of the PUWP. While the results were not spectacular, steady progress was made largely through the organization of agricultural cooperatives and some collective farms. But after 1956, this policy was conspicuously reversed. Most of the cooperatives were dismantled and any serious efforts to proceed further with collectivization were abandoned. Gomulka’s position was a throwback to the line advanced by Nikolai Bukharin in the 1928-29 struggle within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), namely that private enterprise in agriculture would gradually “wither away” as it was surrounded by socialist industry in the rest of the country.

Of course, just the opposite happened. The inefficiency of small-scale production in agriculture itself had a negative impact on the larger economy. The peasants did everything they could to reduce their obligations to deliver foodstuffs to the state sector at fixed prices and to increase the portion of their product they could sell on the “free” market. The latter, in turn, engendered capitalist relations of exchange in a network of wholesalers and retailers throughout the economy, leading to an extensive black and grey market in agricultural produce.

In this situation, it was the Polish working class which ultimately had to shoulder the cost. This happened in two ways. The inefficiency of small-scale agriculture meant that the peasantry was subsidized with artificially high prices for its deliveries to the state in order to maintain its standard of living. This had a negative impact on the overall plan by draining potential investment in industry and was a key factor in the decision to attempt to finance further industrial development in Poland through extensive borrowing from Western banks. In addition, the higher prices for foodstuffs raised the cost of living for the working class. The government responded to this situation time and again by raising wages, further aggravating inflationary pressures as well as undermining both investment and the general social wage of the workers in order to continue to subsidize the Polish farmers and essentially reward them for maintaining backward relations of production.

In fact, it is not too much to say that this disastrous 25-year policy in agriculture is the principal source of the distortions in Poland’s economy which served to unleash the political forces who now pose a challenge to Poland’s very future as a socialist country.

However, the opportunism of the post-1956 general line of the PUWP is most blatant in the party’s ideological surrender to imperialism, fueled by nationalism and anti-Sovietism, and resulting in the disastrous economic policy which made Polish socialism hostage to the Western banks.

Not only did Gomulka’s “Polish road to socialism” deny the usefulness of Soviet experience in socialist construction, especially the important lessons to be drawn from the Bukharin-Stalin line struggle, it also set out consciously to keep Poland less “dependent” on the Soviet Union and the other socialist countries. The inevitable consequence of such an orientation was to strengthen Poland’s ties to the imperialist countries. To be sure, Soviet and East German insistence on maintaining the military and political unity of the Warsaw Pact powers sharply circumscribed this tendency, but within those constraints Poland was the Eastern European country which has maintained the most extensive economic and ideological ties to the West.

The government and party did little to counter the negative ideological effects of an extensive interchange which flourished between the Polish community in the U.S. and friends and relations in Poland. By the mid-1970s this interchange was beginning to play an important role in the already weakened Polish economy. Hard currency gifts from relatives in the U.S., plus U.S. social security payments (in dollars, of course) to several thousand workers of Polish descent who retired to Poland, became an important source of currency speculation, black-market investment, and a sub-rosa private economy which drained tens of millions of dollars out of the socialist sector. The government, anxious for hard currency to enter Poland’s economy in order to meet debt payments, ignored the destabilizing and demoralizing effects of such corruption.

It is also clear that, with the possible exception of Rumania, Poland was the Eastern European country least prepared to assume internationalist responsibilities in the world struggle against imperialism. The party did little, if anything, to educate the Polish masses in the spirit of internationalism or to promote material and ideological support for Vietnam, Angola, etc. The “struggle for socialism” was reduced to improving the life of the Poles, bringing it up to Western standards– period.

The most concrete concession to imperialism was the policy advanced in 1970 by Edward Gierek of tying Poland’s industrial development to a massive program of borrowing from Western banks. The naive logic of the scheme was to develop rapidly a Polish industry whose products in turn would be sold on the world market. The hard currency obtained would be used to pay off principal and interest of the loans and would even provide a surplus for the import of Western consumer products. In fact, the government used a significant portion of the loans (in anticipation of the future pay-offs) to obtain sizeable quantities of Western consumer goods on the assumption that this would keep the masses content.

Of course, as everyone now knows, this scheme was a house of cards. It did more to destabilize the Polish economy than the CIA could have done on its own. But even if it had “worked,” the net long range results would have been to weaken the socialist base of Poland’s economy by tying its future development to the vicissitudes of the world capitalist market. Increasingly Poland’s economy became enmeshed with Western capital while its ties to the socialist economy of the East were steadily weakened. Confusing its friends with its enemies, Poland’s communists played out to its maximum their revisionist illusion concerning peaceful coexistence as the be-all and end-all of a proletarian international line.

Today Poland’s $25 billion indebtedness to Western banks hangs like a sword of Damocles over the head of the Polish working class. Should Poland default on this debt, the consequences would be even more drastic. All Polish assets presently in Western countries would be subject to immediate confiscation. Polish trade with the West would grind to a halt Any Polish ship venturing into a Western port would be subject to legal seizure and expropriation. Poland would not be able to sell its products in Western markets since Western governments would be obliged to block all hard currency payments. Poland would not be able to purchase spare parts or replacements for any of its Western-built technology. In short, Poland would become a pariah in the international community, placing an incredible burden on Poland’s own socialist construction and on the whole socialist camp.

These, in our view, are the principal historical and political causes of the crisis in Poland. The profound political errors of the PUWP brought about a crisis in the economy which, in turn, gave rise to a political crisis which now threatens the foundations and future of socialism in Poland.

The principal responsibility for the present crisis must be placed on the opportunist line and practice of the Polish party which, in effect, abandoned the class struggle both internal to Polish society and internationally. The net result has been the failure to consolidate socialism and the weakening of the dictatorship of the proletariat. The failure to consolidate socialism is expressed principally in the incorrect policy toward the collectivization of agriculture and the distortion of the socialist economy brought about by the scheme for rapid industrial development based on Western financing and investment. The weakening of the dictatorship of the proletariat has been expressed in the widespread bourgeois corruption of party and government officials; the negative concessions made to anti-socialist forces in Poland, most particularly the Catholic Church; the conciliation of bourgeois nationalism, and a general ideological undermining through years of neglect of the political and ideological remolding of the working class under Marxism-Leninism.

Those on the left and particularly in the communist movement who have supported Solidarity as a progressive or even revolutionary force generally do so for two reasons. First, they argue that since Solidarity emerged in opposition to a revisionist party its politics are objectively anti-revisionist. Second, since solidarity has apparently been able to establish more of a base in the Polish working class than the PUWP has, it is the genuine representative of the proletariat.

It is hard to imagine a more superficial and simplistic approach to politics. Communists have long since recognized (although some often forget) that not every expression of opposition to the bourgeoisie is revolutionary or even necessarily progressive. Historically fascist movements have risen and achieved a mass following on the strength of agitation against many of the ills of capitalism. By the same token, Solidarity’s opposition to the PUWP cannot be deemed automatically anti-revisionist just because it arises in opposition to a revisionist party. Nor can a base in–or even majority support from–the Polish working class be considered a sure-fire proof that the line of any movement or organization represents the real interests of the working class. (By such mechanical criteria, the U.S. Democratic Party could be considered a party of the working class, or the imperialist army could be viewed as an expression of the armed proletariat).

Let us not mince words. A movement must be judged objectively by its line and leadership. The Polish workers who have given Solidarity their support have not thereby automatically verified Solidarity’s proletarian politics. In our opinion they have more precisely verified the extent of the political and ideological backwardness among the Polish working class, the degree of false consciousness and misplaced militancy. True, the principal responsibility for the backward state of the Polish working class must be laid at the doorstep of the PUWP. Of this there can be no doubt But the responsibility that the PUWP must bear for this sorry state of affairs does not in any way change the political substance of the Solidarity-led movement.

How then shall we determine the politics of Solidarity? Well, for one thing, we must go beyond the general slogans and official statements of purpose of the organization (which we would naturally expect to be phrased in the most positive-sounding manner) and examine more closely the actual program that Solidarity advocates and would implement if it held power. Here we would have to pass judgement on the actual content and consequence of those policies irrespective of the rhetoric used by the Solidarity leadership to characterize them.

Second, we would more closely examine the actual political forces who make up the leadership of Solidarity in order to determine their general political orientation toward the class struggle both in the policies they may advocate at any given moment and in their more far-reaching perspectives.

And finally, we would take into account who makes up Solidarity’s supporters and allies both inside Poland and internationally. This is based on the not unreasonable assumption that many of the diverse “friends” of Solidarity function in a conscious and sophisticated fashion and believe that their own political purposes are served by such support.

The popular impression of Solidarity’s political program is that it is a program for “workers’ control.” And, of course, nothing could sound more democratic or more socialist. But Solidarity’s actual program of “workers’ control” has built into it just the opposite: it is laced with all kinds of anarcho-syndicalist, social democratic, and Trotskyist prejudices and amounts to the abandonment of socialism and the surrender of the proletarian dictatorship. To demonstrate this point, let us examine the concrete program that Solidarity advocates in three crucial areas: agriculture, industry, and democracy.

What would Solidarity do about the question which, probably more than any other, is at the root of the distortions in Poland’s economy: agriculture? Not even its most ardent left-wing supporters would dare suggest that Solidarity stands for anything other than strengthening the role and position of the independent farmer, of petty commodity production in Polish agriculture. The organization has given unwavering support to all the demands of Rural Solidarity, the political association of peasant land-holders which sprang to life in the wake of Solidarity’s own growth.

Rural Solidarity calls for nothing less than dismantling the existing state and collective farms and the transformation of all of Polish agriculture to capitalism. That is the long-range goal. On the way to that strategic objective, Rural Solidarity has a more immediate program.

First, it calls for increasing the legal limits on the size of private plots. This would be accomplished in two ways: by breaking up the state farms and selling the land to peasants, and by permitting the wealthier landholders to purchase the land of other peasants. It does not take an unduly vivid imagination to see where all this is leading. Poor peasants– those whose present holdings are smaller, whose lack of capital prevents full utilization of the land, who suffer reverses of one kind or another– would be able to sell their property to more successful farmers. They would, at the same time, become the pool for a new agricultural proletariat. The iron laws of capitalism would work so as to constantly increase the size of the rich peasants’ holdings bringing into being a new kulak class, that is, a class of capitalist farmers.

Second, Rural Solidarity calls for reducing the portion of agricultural production which must be sold to the state at fixed prices and expanding the free market in agricultural commodities. Eventually, of course, any obligations to the state sector would be completely abolished and only a capitalist commodity market would govern agriculture. Capitalist speculation and hoarding would become legal and respectable. (It is already widespread but illegal.) This program would mean firmly implanting the capitalist mode of production in a key sector of the economy. The free market in agricultural commodities would inevitably give rise to related free markets in distribution, food processing, etc., thus extending the process of undermining socialism to manufacturing and industry as well.

Third, Rural Solidarity demands across-the-board price increases to the farmers now. While supporting this demand, Workers’ Solidarity itself continues to oppose raising retail prices on foodstuffs. Instead it calls for increasing wages (as well as the subsidy to farmers) and argues that the resources to pay for all this can be obtained by cracking down on official corruption and making industry more efficient. This aspect of Solidarity’s program is not only economically naive but also highly inflationary and could only intensify the present economic difficulties. Moreover, that such a contradictory and unrealistic proposal was a political ploy to weaken the government and strengthen the dual power of Solidarity can not be dismissed out of hand.

Fourth, Rural Solidarity demands a pledge from the government–one that Solidarity was prepared to make for itself–that all plans and programs that would further the collectivization of agriculture be abandoned. Rural Solidarity also demands that present policies which give priority to the state and collective sector be reversed.

Finally, Rural Solidarity openly states that its own aim is political control of the countryside. In other words, instead of a workers’ government exercising control over the economy as a whole, an organization of peasant property-owners would exercise control over one portion of it.

The conclusion is inescapable: Solidarity’s program in relation to agriculture would only strengthen capitalism in the countryside and inevitably lead to the restoration of capitalism throughout the Polish economy–regardless of whether or not this is the conscious intent of many Polish workers and Solidarity supporters.

Solidarity’s catchwords concerning its program for Polish industry are “workers’ control” and “decentralization.” Summing up Solidarity’s national congress in September, the Wall Street Journal stated: “The Solidarity plan.. . calls for dismantling most central directives and seeks to make enterprises self-financed entities, whose strategies and product mixes are shaped by market forces rather than by state plans.”[7]

Naturally, all of the latent anarcho-syndicalist tendencies within the Western left have been roused to a high pitch of enthusiasm over such prospects. But far from being a plan for the strengthening of socialism, such a policy is actually a primitive program for dismantling the socialist planning mechanism and reintroducing anarchy of production.[7a]

The “self-financing” of every enterprise means that both prices and wages would be tied to the profitability of each business entity. The lack of central planning would mean that each enterprise would compete with every other one for accessibility to raw materials, distribution outlets, even display space in retail establishments. Steel, for instance, would be allocated to various factories on the basis of price, with the decision to be made by the self-managing workers at the steel plant; decisions based on social need (rather than profitability), which can only be made at the society-wide level and not at the enterprise level, would become a thing of the past.

The chaos and anarchy of such primitive socialism began to be played out weeks before the martial law showdown. As levers of the economy began to fall under the partial control of local chapters of Solidarity, all the telltale signs of disorganization and lack of central control in production began to emerge and paralyze the economy. Since a nationwide market mechanism was lacking, the anarchy took the initial form of primitive barter and commodity exchange with the classic example of striking coal miners threatening to directly exchange “their” coal for potatoes!

What should also be borne in mind is that this anarcho-syndicalist program was actually the expression of Solidarity’s “moderate” wing, represented by economist Ryszard Bugaj, who stated with the “realism” which has become the typical style of much of the Solidarity leadership, “There had to be a balance of what we wanted and what we are able to achieve.”[9]

But, as the Wall Street Journal further reports:

Those who wanted more drastic measures have been disappointed by the union’s program. The most bitter feud was that between Mr. Bugaj and the union’s other top economist, Stefan Kurowski, who wanted Poland’s entire economic system to be changed, not in progressive steps but with one big sweep of capitalism. ’The time is very limited,’ argues Mr. Kurowski. ’There will be very high social and political costs if this crisis lasts for years. The direct influence and interference of political parties in economic activity should be liquidated.’

Among other things, his plan calls for: cutting military spending in half, thereby freeing 5% of Poland’s national income for the productive sector; dismantling branch ministries and middle-level planning agencies to erase the government’s means of central economic control; opening up the market to private and foreign capital. Mr. Kurowski argues that Poles have some $3 billion in hard-currency accounts (legal in Poland since 1976), which could give the economy new impetus.[10]

Is it not clear that the difference between “moderate” and “extreme” in Solidarity was fundamentally a difference over the pace of these changes in Poland’s economic structure or the willingness to openly face up to their actual consequences? (On the latter count, the “extremists” appear to have been more politically sophisticated.) In any case, the conclusion is again inescapable. Solidarity’s policy in relation to industry would fundamentally dismantle the planned socialist economy and pave the way for the full restoration of capitalism in production and exchange.

But what about Solidarity’s demand for democracy? Can the left seriously be expected to oppose Solidarity’s demands for free elections, freedom of speech, press, and political association? For Trotskyists and social democrats of all hues the answer is definitely “no!” The question of “democracy” has become a matter of principle within these quarters of the left. Among communists, however, the question tends to be posed as a matter of tactics–whether or not the possible isolation we risk among U.S. workers is too great a price to pay for the defense of such an unpopular and compromised cause as Polish socialism.

However, difficult as it is, this has long been one of the key questions of theory and practice which has separated the communists from the opportunist trends in the socialist movement–at issue here is the notion of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Communists who insist on dealing with “democracy” as a question of absolute principle are merely demonstrating that they have not yet understood (or refuse to understand) the actual content and purpose of proletarian politics. For the revolutionary proletariat, democracy can only be viewed as a class question, subordinate to the class struggle. Democracy for whom? Democratic rights to accomplish what political ends? These are the crucial questions. Under one set of circumstances, a very broad conception of democracy may be desirable. In other circumstances certain rights may be sharply curtailed. Any communist who cannot grasp this fundamental truth has not yet understood the ruthless nature and inexorable laws of the class struggle.

It is only in this context that we can evaluate from a Marxist-Leninist point of view the class context of Solidarity’s demands for the extension of democracy.

First of all, it is obvious that Solidarity was primarily demanding for itself the legal right to promote, popularize, and implement the anti-socialist program we have analyzed above.

Second, the chief political beneficiary to date of the demand for the extension of democracy has been the Catholic Church, that is, the principal political and ideological representative inside Poland of the ousted bourgeoisie and world imperialism. From the outset, Solidarity has linked itself with the Catholic Church and fought with determination for its right to advance its ideology and political goals without hindrance or restriction from the socialist state.

Finally, Solidarity’s demand for democracy has explicitly included the demand that anti-socialist forces be guaranteed the right to organize and proselytize openly and legally for their views. Solidarity’s demands for freedom of speech and release of political prisoners have always included demands on behalf of some of the most notorious counterrevolutionary and anti-semitic figures in Poland, individuals who do not even bother to disguise their reactionary views.

Of course much of the mass sentiment in favor of Solidarity’s demand for democracy has been in reaction to the grossest violations of proletarian democracy over an extended period of time on the part of the party and government officials. Despite this, the notions of “freedom” and “democracy” advanced by Solidarity are thoroughly bourgeois– both in form and content In agriculture it amounted to the freedom to expand and engage in capitalist production and exchange. In industry it was the freedom of the market to supplant centralized planning and the right of sections of the workers at the enterprise level to lay claim upon the social means of production. In politics, it called for an unrestricted guarantee of freedom to the very forces the proletarian power would otherwise restrict and/or suppress in defense of the overall and long range interests of the working class. The bottom line of Solidarity’s notion and practice around the extension of democracy amounted to a qualitative weakening and dismantling of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Granted that many of the mass members and supporters of Solidarity were not conscious of the negative consequences of their program for more “democracy,” the same cannot be said for the functioning leadership of Solidarity. The only political force on which Solidarity ever called for restrictions was the communist party and its favored position to propagate Marxism-Leninism as the official ideology of the Polish state!

In summation, a careful examination of the actual program of Solidarity reveals that its objective effect was to steadily weaken the economic and political position of the working class in Polish society– while strengthening the power and position of opportunist and anti-socialist elements and forces.

A general impression on the left seems to be that by and large the political leaders of Solidarity are militants who have emerged from the spontaneous self-mobilization of the working class, guided to some extent by individuals like Walesa and certain Marxists with the elements of an anti-revisionist critique of the PUWP.

The U.S. press has tended to reinforce this picture with Walesa portrayed as a highly emotional individual, naturally charismatic, a devout Catholic motivated out of Christian principles, trying his best to ride herd on a spontaneous movement which keeps running ahead of him. Although there is an element of truth to this, it is in the main wishful thinking, quite divergent from the facts of the matter.

The political leadership of Solidarity is a highly conscious group embracing virtually every rightist tendency with any kind of base in Polish society, including bourgeois nationalists, pro-U.S. forces, open advocates of capitalist restoration and even proto-fascism. Its most “left” element, the Committee for Self-Defense (KOR), might most precisely be labeled social democrats (whose critique is not of revisionism, but Marxism-Leninism). Jacek Kuron, KOR’s leading figure and Walesa’s closest adviser, recently announced the dissolution of KOR declaring that it “has fulfilled its function. Our program was realized 100%. With Solidarity’s existence, KOR has become superfluous.”[11] Much of the intellectual scaffolding of Solidarity, in particular at the national level, consisted of members of KOR.

Walesa himself probably represents the political center of Solidarity. His closest ties are with the Catholic Church. Much of his “moderation” is a reflection of his own pragmatic common sense, but more importantly of the general tactical approach taken by both KOR and the church; that is, to build political power gradually, step by step, avoiding a direct confrontation with the state and possible intervention by the Soviet Union until such time as a powerful mass base could be built up that might hold both the Polish state and the USSR in check. (Since the Marxist-Leninist crackdown, the Catholic Church apparatus–directed from the Vatican–is skillfully attempting to use its privileged position to mediate and rescue the Solidarity movement and prepare for its eventual re-emergence, providing a crucial insight on the political sophistication of this reactionary organization.)

A rare glimpse into the political tensions and actual balance of political forces within Solidarity was provided at the September congress of the union. There Walesa and the KOR group maintained control over the organization–but just barely. A growing sector of the Solidarity leadership with a more explicitly rightist outlook was breathing down Walesa’s neck.

The most detailed analysis of the various political forces in Solidarity was offered in a series of remarkable reports which appeared in September and October in the Wall Street Journal. Unlike much of the left, which is satisfied to wallow in political platitudes about Solidarity, this organ of monopoly capital was after a more precise political portrait of the organization. The following descriptions are taken from this series.

The man widely considered “the most radical member of Solidarity’s presidium and perhaps the second most important Solidarity leader after Lech Walesa”[12] until his resignation shortly before the declaration of martial law was Andrez Gwiazda. He is the one who has most consistently pushed for confrontation with the government and issued the calls for “free trade unions” similar to Solidarity to be organized in the other Eastern European countries. At the Solidarity Congress, Gwiazda opposed every resolution proposing any kind of economic program that might be jointly developed between Solidarity and the regime. “It’s impossible to set up any working economic system under the current doctrine,” he declared. “All sensible economic conceptions contradict the ideology of the government.”[13]

Another important force in Solidarity is a bloc which more or less follows the political leadership of the avowedly anticommunist Confederation for an Independent Poland (KPN). This is “a conservative group that has long been ruled by the desire for an independent and nationalist Poland. It is also tainted by a history of anti-semitism. It hasn’t placed its leaders in high union offices, but delegates estimate that about 100 of the 829 delegates at the National Congress were at least KPN sympathizers. The group has its broadest backing at the factory level, and its greatest popularity is in the conservative Silesian coal mining region in southwest Poland.”[14]

A figure commanding significant support within solidarity is Jerzy Milewski who received 275 votes in the balloting forthe union’s national council. His aim is to found a Polish Labor Party which, he says, “will be a West European type centrist party like the British Labor Party 80 years ago.”[15] Then there is Arkadeusz Rybicki, editor of a Solidarity newsweekly in Gdansk, whose aim is the launching of a Christian Democratic Party, which would “be closely aligned with the Catholic Church, of which more than 90% of Poles are members. The accent would be on Polish patriotism and the goal would be greater Polish independence.”[16]

What all this adds up to is that while much of the left, displaying little attention for the facts, has waxed rhapsodic over Solidarity’s “socialist impulse,” the concrete political makeup of the union leadership demonstrates conclusively that it had become the magnet and breeding-ground for the most diverse spectrum of counter-revolutionary forces in Poland.

In view of Solidarity’s political program and the nature of the political forces who dominate its leadership, it is hardly surprising that support for Solidarity has come from all the chieftans of world imperialism. The curious sight of Ronald Reagan piously declaring that the hearts of America and the “Free World” are with the Polish masses in their moment of harsh trial, while Alexander Haig “diplomatically” calls for a “workers’ revolt” in Poland, is a bit sobering for leftists with the thickest rose-colored glasses. However, the principal instrumentality for expressing U.S. imperialism’s support to Solidarity has been, naturally enough, the leadership of the AFL-CIO.