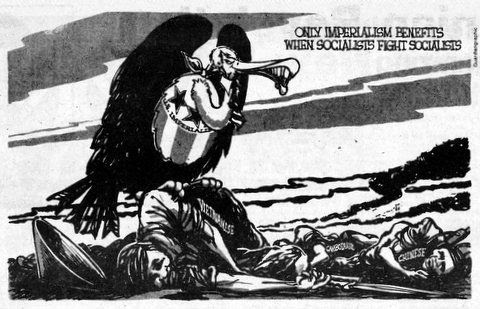

The anti-revisionist movement as a whole found itself in paralyzing disarray in the aftermath of Mao’s death and the changes in Chinese policy following the arrest of the Gang of Four. The “anti-dogmatist trend,” formed in response to China’s new alliance with the U.S., broke sharply from the pro-China camp, but was unable to forge any significant degree of unity of its own.

The trend emerged after the initial break of many left forces (mostly outside the New Communist Movement) with China’s position on the war in Angola. The trend joined these other left forces in supporting Cuba’s military intervention on behalf of the post-colonial Luanda government.

The four principal components in the trend were:

* the Organizing Committee for an Ideological Center (OCIC), formed in 1978;

* the rectification movement, which went public in 1979;

* the groupings loosely united around the Theoretical Review (TR) journal,

* and the Guardian newspaper.

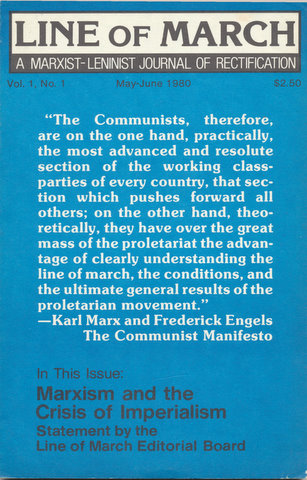

Rectification forces had their origins in the Guardian Club network, but broke with the paper over a host of issues. Rectification’s first public manifestation was the National Network of Marxist-Leninist Clubs. After the first issue of the journal Line of March appeared in May-June 1980, activists in the rectification network began to be known by that name.

At the start, most of the trend (OCIC, the Guardian and rectification) seemed prepared to accept the major premises of the original Chinese critique of revisionism. These included identification with pre-1956 Communism as “revolutionary” (with some willing to take a less adulatory view of Stalin than many in the New Communist Movement did) and rejection of Soviet politics from Khrushchev on as “revisionist.” The TR was more disdainful of Stalin-era theory, more critical of pre-1956 Marxism-Leninism, and looked more to Western Marxism (Gramsci, Althusser, Poulantzas, etc.) for its theory.

At first cautiously, but in time much more openly, trend forces broke sharply with China and the New Communist Movement’s assessment of the Soviet Union, including questioning the analysis that capitalism had been restored in the Soviet Union and that it had become a social imperialist state. Line of March in particular moved toward an openly pro-Soviet position.

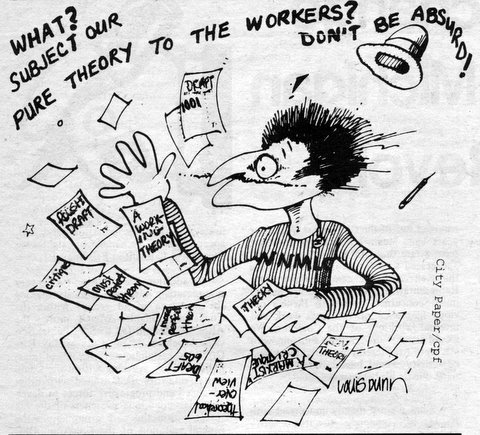

The main point of contention among the various “anti-dogmatist” forces was the approach to party building. The OCIC advocated prioritizing recruiting workers to achieve “fusion of communism with the workers’ movement.” The Guardian newspaper and the Theoretical Review prioritized theoretical production. However, once the Guardian lost its Club network, its interest in the party building noticeably declined. Supporters of rectification propagandized for party building based on developing a general political line rather than the broader theoretical production and discussion advocated by TR.

Hostilities over the “fusion vs. rectification” polemics solidified the two largest groups into opposing camps. OCIC, following the lead of the well-established Philadelphia Workers Organizing Committee, argued that any party that did not prioritize recruiting workers would be irrelevant – especially since, like all the New Communist Movement groups, the trend drew heavily on former student activists and those from social movements outside of labor (though not necessarily from high-income backgrounds).

The OCIC formalized a developing relationship with local independent collectives involved in working class organizing in various urban centers. Rectification drew its ranks from activists in a number of small Marxist groups, including the national Union of Democratic Filipinos, the Northern California Alliance, and the Third World Women’s Alliance. It also had influence among activists of color involved in the struggle around San Francisco’s International Hotel, and the National Coalition to Overturn the Bakke Decision.

The rectification network took a leaf from “What is to be Done?” and sought to make the OCIC a foil in the style of the Bolshevik/Menshevik debate. Their orientation contrasted with the “workerism” of the local collectives that made up the OCIC. Rectification also drew heavily on the party building line of the Communist Party of the Philippines, a Maoist group that split from the Moscow line party in the late 60s, founded by youth leader Jose Maria Sison. That party stressed an ideological continuity with the old party’s “revolutionary” past, while forging an alternative to its latter-day “revisionism” by developing a “rectified” general line around which a “re-established” party would be built among the masses of workers.

While OCIC disdained the “intellectualism” of the forces around TR, rectification forces considered TR’s turn from orthodoxy too close to apostasy. Rectification identified more strongly with what Max Elbaum described as “Third World Marxism,” drawing from Mao (initially), Le Duan of Vietnam, Fidel Castro, etc., as well as Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin and Dimitrov.

Given these very real differences, no effective unification of trend forces was possible. While Line of March and the Theoretical Review network continued to grow and go their separate ways into the early 1980s, the OCIC imploded when it launched a bitter internal witch-hunt against “white chauvinism.” The crisis which would ultimately result in the demise of the trend was only a microcosm of the broader overall crisis of the U.S. left which characterized the 1980s.

The Trend by Ethan Young

“Me Start a Vanguard Party to Lead the Working Class to Revolution? You Must Be Kidding!!” by the Buffalo Workers Movement

Silber, Newlin Debate on Party Building by John Reed

On The “Progressive Role” of the Soviet Union and Other Dogmas: A Further Reply to the PWOC and the Committee of Five by the Proletarian Unity League

Leading “Anti-Dogmatists” Debate by The New Voice

Ideological Obscurantism & the Silber-Newlin Debate by the Chico Collective

Ex-Maoists On the Road to Moscow: Where Is the “Trend” Going? by the Spartacist League

PWOC Holds Second Annual International Women’s Day Celebration

PWOC Political Committee Statement: The Horn of Africa

Zaire in Crisis by Jennie Quinn

CP-ML on Zaire – Spreading the Word for Brzezinski by Jennie Quinn

Silber, Newlin Debate on Party Building by John Reed

From the Staff... Organizer begins fifth year

Editorial: A New War in Southeast Asia

US Recognizes the People’s Republic of China

The PWOC’s “Leftism”: A Self-Criticism by Clay Newlin

China and Vietnam and the Question of War by the PWOC Political Committee

An Exchange on May Day... Unity at What Price? between the Revolutionary Workers Headquarters and the Philadelphia Workers Organizing Committee

Speech on the “State of the Party Building Movement” by Clay Newlin

How the CPUSA “Beat” Frank Rizzo by Ron Whitehorne

NNMLC Develops The Subjective Factor: Re-establishing the “Left” Line on Party-Building by Clay Newlin

CP-ML and PWOC on International Line by Ron Whitehorne

“Rectification vs. Fusion”: Why Not? by Clay Newlin

Has the PWOC Changed Its Line on Fusion? by Clay Newlin

Idealism and “Rectification” by Clay Newlin

Party-building: PWOC view of the Proletarian Unity League. On theory, unity and fusion (first in a series) by Clay Newlin

Party-building: PWOC view of the Proletarian Unity League. Political line and party-building (third in a series) by Clay Newlin

Party-building: PWOC view of the Proletarian Unity League. PUL’s Distortion of the ’left’ Line (fourth in a series) by Clay Newlin

Proletarian Unity League Responds: Fusion and the “Anti-Dogmatist” Phrase

A Response to PUL: Clearing Away the Fog by Clay Newlin

Irwin Silber vs. the Guardian Staff. Cut Out the Warts, Spare the Cancer by Clay Newlin

Letter to the Philadelphia Workers Organizing Committee Political Commission by Irwin Silber and Frances M. Beal

Reply to Silber/Beal Letter by the Philadelphia Workers Organizing Committee

Letter from Irwin Silber and Frances M. Beal to the PWOC Political Commission

Letter from the Philadelphia Workers Organizing Committee to Irwin Silber and Frances M. Beal

[Back to top]

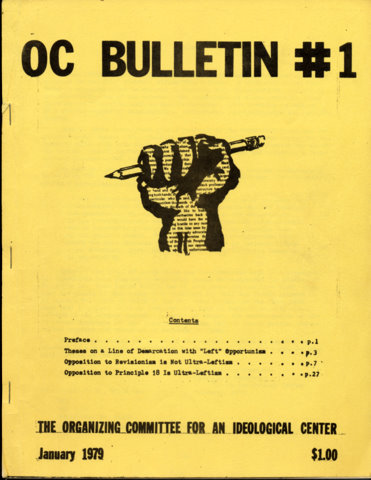

In February 1978, four of the groups which had constituted the Committee of Five – the Philadelphia Workers Organizing Committee (PWOC), Socialist Union of Baltimore, Potomac Socialist Organization and the Detroit Marxist-Leninist Organization – met in Detroit with other smaller collectives and founded the Organizing Committee for an Ideological Center (OCIC). PWOC leader Clay Newlin was elected as its chair.

A number of groups declined to join the OCIC. These included the Guardian and the rectification movement. El Comite/MNIP did not affiliate, arguing that the objective conditions necessary for a viable new movement were lacking. The Bay Area Socialist Organizing Committee (BASOC), also declined to join, arguing that the OCIC’s points of unity were shallow and did not represent a coherent enough political program to guide a national organization and that the OCIC’s formulas made little provision for the theoretical work or strategic discussions that BASOC felt were necessary. Nonetheless, the OCIC encompassed the bulk of the anti-dogmatist, anti-revisionist forces.

By early 1979, the OCIC included over 20 organizations in twenty cities, with a combined membership of some 350 individuals. Most of the groups were small. Only 4 had over 20 members; half of the remaining groups had 11-20 members, while the rest had 1-10 members. All OCIC groups were less than ten years old; only a handful were over four years old and, of those, half had been democratic centralist formations for a much shorter period of time. Indeed, only half of the OCIC groups were “democratic-centralist or in the process of developing democratic-centralism.”

OCIC groups were also weak in working class and minority composition. While membership was equally divided between men and women, the Steering Committee report indicated that only 3% of all OC members were workers and only one organization was composed of people who “developed out of the class struggle.” The OCIC membership contained only 25 national minority members (7%) with ten groups having national minority members, but only one being “really multi-national.”

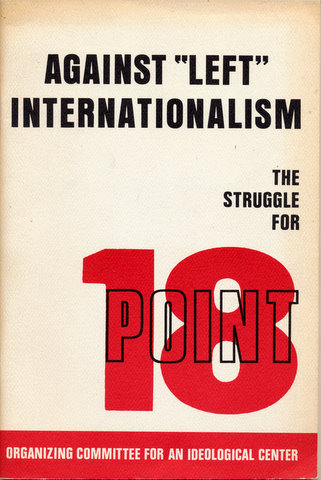

The major struggle in the OCIC in its first year was over Point 18 of its Points of Unity – the definition of US imperialism as the main enemy of the peoples of the world. This fight demarcated the OCIC from those anti-left opportunist forces who continued to argue that “Soviet social imperialism” was an equal or greater threat. By the OCIC’s second conference, in September 1979, this issue was largely settled and the OCIC turned its attention to organizational consolidation through the building of local and regional centers and the struggle against federationism.

However this effort was hampered by lack of unity within the OCIC around a party building strategy, OCIC groups being divided between proponents of the fusion line, those advocating “primacy of theory” and those which either had not studied the question or failed to adopt a position. As a result or this and similar ideological differences, the OCIC was unable to get its projected theoretical journal off the ground and failed to mount any nationally coordinated campaigns.

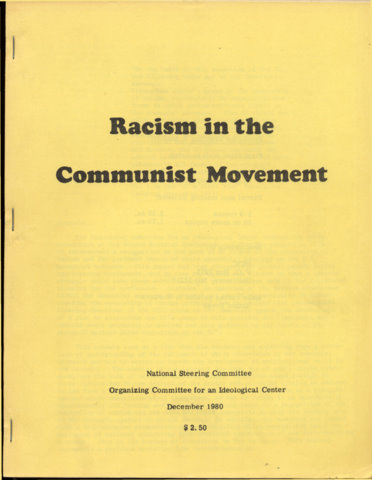

Notwithstanding these weaknesses, after the second OCIC conference, the Steering Committee abandoned its original cautious and consensus-building approach and turned to a high-intensity ideological campaign to consolidate the network. The campaign’s target was white chauvinism and identified the alleged racism within the membership as the OCIC’s key problem. Beginning in PWOC itself, the campaign consisted of lengthy criticism sessions dissecting individuals’ attitudes and psychology. The effort was all but completely divorced from any kind of grounding in practical work, demagogy ran rampant, and during its peak the campaign turned into the worst kind of sterile purification ritual.

The chief targets of the white chauvinism campaign were opponents of the OCIC’s consolidation around the Steering Committee and its line. When members protested the way the campaign was being conducted, the leadership responded that its critics were merely defenders of racism. Soon members started leaving in droves. During 1981 every OCIC activity except the campaign ground to a halt, and in October PWOC’s Organizer newspaper admitted that the OCIC was “near-collapse” with “functioning local areas reduced from 18 to 6 and 80% of the membership resigned.” PWOC itself was also in shambles. By the spring of 1982 both PWOC and the OCIC were defunct. Other OCIC materials on and responses to the campaign against white chauvinism from 1980-81 are included in the New Communist Movement: Collapse and Aftermath page of EROL.

Response to the debate among the anti-’lefts’. Soviet Union: Friend or Enemy? by Carl Davidson

CP-ML and PWOC on International Line by Ron Whitehorne

Letter to The Call by the Proletarian Unity League

Fight on Two Fronts by Carl Davidson [of the Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist)]

Minutes of the [Founding] Conference on the Ideological Center

Proposal As Amended at the February Conference

Initial Overview of the OC by T.V., Secretary, OCIC Steering Committee

* * *

Summary of the Proceedings of the First Meeting of the Steering Committee of the OCIC

Theses on a Line of Demarcation with “Left” Opportunism

Summary of the Proceedings of the Second Meeting of the Steering Committee of the OCIC

Founding Statement of the Organizing Committee for an Ideological Center

A Brief Statement on the Struggle Against Racism

Summary of the December 1978 Meeting of the Steering Committee of the OCIC

Proposal for an OCIC Discussion Bulletin

Study Guide for the Eighteen Points of Unity

Is International Line a Correct Line of Demarcation within the Anti-“left” Tendency? by the Communist Unity Organization

Letter from the Boston Party-Building Organization to the OCIC Steering Committee

Point 18 as a Line of Demarcation by the Tucson Marxist-Leninist Collective

Against “Left” Internationalism. The Struggle for Point 18

Report to the Bay Area Socialist Organizing Committee on West Coast Point 18 Conference

OC-IC Holds Conferences to Debate International Line and Party Building by Clay Newlin

Our Unity Must Be Concrete – An Argument for Unity on Pt. 18 As a Line of Demarcation for OCIC Membership by the Milwaukee Socialist Union

Conference Presentation: The Particular Tasks of National Minority Marxist-Leninists by Leslie Roberts

Conference Presentation: Speech on Party Building by Tyree Scott

Conference Presentation: The Struggle Against Sexism by Sylvia Kimura

Resolutions of the OCIC National Minority Marxist-Leninists Conference

Open Letter to the National Minority Conference Planning Committee by members of the Sunday Morning Group (Los Angeles)

Conference Held... National Minority Marxist-Leninists by Michael Simmons

Criticism/Self-Criticism of the National Minority M-L Conference by Eileen E.

Letter to the Organizer on the National Minority Marxist-Leninist Conference by Eileen E. and Nobuo N.

Conference Presentation: Speech on Party Building by Tyree Scott

Evaluation of Minorities Conference by Nobuo N.

* * *

The OC’s First Year by the National Steering Committee OCIC

Comments on The OC’s First Year by the Milwaukee Socialist Union

A Key Weakness in The OC’s First Year by the Cincinnati Comrades

Forging the Party Spirit – A Beginning Perspective by JF for the National Steering Committee OCIC

* * *

Second National OCIC Conference: Conference Transcripts and Resolutions

Resolution on the OC’s First Year

Resolution on the National Minority Marxist-Leninist Conference

Other Resolutions Adopted at the Conference

Draft Plan for a Leading Ideological Center

A Proposal Concerning National Pre-Party Organization During the IC Period by the Louisville Workers’ Collective

Steering Committee Presentation on the History and Conception of OCIC Centers

Outline of NSC’s Summation of the National OCIC Conference

National Steering Committee Sum-up of the Second National Conference of the O.C.I.C.

COG Evaluation of National OCIC Conference by the Chicago Organizing Group for a Local Center

* * *

A Criticism of the OCIC Labor Day Conference by the Louisville Workers’ Collective

Proposed Revision of the Draft Plan on the Question of the Relationship of Theory and Practice in this Period and the Role of National Pre-Party Organization by the Louisville Workers’ Collective

Put the Tendency on a Firm Basis by the Minneapolis Socialist Committee

Summary of the October 1979 Meeting of the Steering Committee of the OCIC

Speech on the Draft Plan for a Leading Ideological Center by Dave F.

Ultra-Leftism Task Force Proposal

Conciliation of Ultra-Leftism and OC Membership by the OCIC Steering Committee

OCIC Steering Committee Overview by Clay Newlin for the OCIC Steering Committee

Critique of Recent OCIC Practice by the Bay Area Workers’ Organizing Committee “Minority”

Where SOC Stands by the Socialist Organizing Committee

Draft OCIC Minority Platform by the Theoretical Review

Conciliationism in Command: An Analysis of Theoretical Review’s “Minority Platform” by Clay Newlin for the OCIC Steering Committee

Descriptive History of the Chicago Organizing Group [and its dissolution]

Summary of the March 1980 OCIC Steering Committee Meeting

OCIC 18 Point Study Guide. (Part 1) Principles 1-5

National Steering Committee Response to Letters About Labor Day Conference

Study Guide on Federationism by D.W. for the OCIC Steering Committee

The Russian Party Building Experience: A Guide for the “Struggle Against Federationism” by the Tucson Marxist-Leninist Collective, Bay Area Workers Organizing Committee “Minority” and Boston Political Collective (M-L)

Draft Outline for Statement on Federationism and the OCIC by the Bay Area Workers’ Organizing Committee “Minority” and Tucson Marxist-Leninist Collective

Resolution on an Ideological Campaign against White Chauvinism by the OCIC National Steering Committee

Summary of the June 1980 OCIC National Steering Committee Meeting

Revisions in OC Work Plan by the National Steering Committee OCIC

The Main Danger Today by Clay Newlin for the National Steering Committee OCIC

Summation of Errors Made in the Election of the Midwest Regional Steering Committee by the National Steering Committee OCIC

Racism in the Communist Movement by the National Steering Committee OCIC

Brief critique and summarization of racism at 1st local Center meeting of D.C.-BA

Resolution on Racism at the 1st local center meeting of D.C.-BA by the D.C.-Baltimore Local Center Steering Committee

Proposed Amendment to “Resolution on Racism at the 1st local center meeting of D.C. BA”

Self-Criticism of My Racism: Breaking the Conspiracy by Terry M.

“Minority” Speech on Federationism Presented at OCIC Western Regional Conference by the Bay Area Workers Organizing Committee “Minority” and Tucson Marxist-Leninist Collective

“Minority” Resolution on the OCIC

Agenda Item to be Added: Resolution on Racist Errors Surrounding the NMMLC Resolution passed at the OCIC National Conference by the Planning Committee, Western Regional Conference

Letter to the OCIC Western Regional Conference: Criticism of the OCIC Discussion on the NMM-LC by Eileen E. and Nobuo N.

“Minority” Presentation on National Minority Conference Resolution

“Minority” Resolution on the NMM-LC and Process

Draft Resignation Letter by the BAWOC “Minority”

July 4th: Report on the OCIC Western Regional Conference by Paul Costello

Letter on the Results of the OCIC Western Regional Conference by Charles K.

The OCIC’S Campaign Against White Chauvinism: A Setback for Our Movement by Tom K.

Federationism and Racism in the New England Regional Center by the New England Regional Steering Committee OCIC

Carry Through the Campaign against White Chauvinism by the New England Regional Steering Committee OCIC

Addendum: Federationism and Racism in the New England Regional Center by the New England Regional Steering Committee OCIC

Our Disagreements with the Present Methods of “Sharp Ideological Struggle”

In Defense of the Campaign Against White Chauvinism – A Response to “Our Disagreements With The Present Methods of Sharp Ideological Struggle” by the New Bedford/Fall River/Providence Local Center Steering Committee

The OCIC: To Be or Not To Be, That is the Question by Dennis F.

Resolution #1: Carry Through the Struggle Against White Chauvinism by the New England Regional Steering Committee OCIC

Resolution #2: Carry Through the Struggle Against White Chauvinism Correctly

OCIC Theses on the National Network of Marxist-Leninist Clubs

NNMLC Develops The Subjective Factor: Re-establishing the “Left” Line on Party-Building by Clay Newlin

Speech on the “State of the Party Building Movement” by Clay Newlin

OCIC Steering Committee Statement on the NNMLC Study Projects

“Rectification vs. Fusion”: Why Not? by Clay Newlin

OCIC Steering Committee Letter to the National Network of Marxist-Leninist Clubs

Idealism and “Rectification” by Clay Newlin

[Back to top]

The Guardian newspaper had inaugurated the Guardian Club network in 1977 as its particular contribution to the party-building movement of anti-revisionist, anti-dogmatist forces [see EROL section: The Birth of the Anti-Revisionist, Anti-Dogmatist Trend, 1976-77]. However, one year later, sharp differences emerged in both the Guardian staff and in the Clubs over party building, their relationship to other trend forces, and the future direction of the Clubs themselves. In the Guardian staff, Executive Editor Irwin Silber articulated a minority position which supported a majority of the Clubs in their desire to move in the direction of the developing rectification movement. Unable to convince the rest of the Guardian staff to support his views, he resigned his positions with the paper in 1978.

In 1979, the differences between the Guardian staff and the Clubs came to a head with the paper making a decision to dissolve the Club Network. The Clubs refused to disband and instead reconstituted themselves as the National Network of Marxist-Leninist Clubs. The new Network quickly became the organizational expression of the rectification line in party building. With its loss of the Club Network, the Guardian’s role as an organized force in the trend’s party-building movement was over.

The State of the Party Building Movement–July 1978 by the Guardian

Proposed amendment to the document, “The State of the Party-Building Movement–July 1978” by Irwin Silber

Proposed amendment to the document, “The State of the Party-Building Movement–July 1978” by Jack A. Smith

Organizing the Struggle for Unity. A Response to the Guardian Staff’s Statement on “The State of the Party-Building Movement” by the Charles River Study Group

Letter of Resignation by Irwin Silber

Letter to the Guardian Clubs by Irwin Silber

Reply to Irwin Silber’s Letter to Guardian Clubs by Jack A. Smith

Statement of the Club Network (formerly Guardian Clubs)

Protest Letter from Members and Supporters of the Guardian Bureaus

Guardian staff view of a complicated political struggle: The Guardian, Silber and the Clubs by Jack A. Smith

[Back to top]

The original core of the rectification network came out of overlapping circles of activists in the Bay Area. In the early 70s, a class on Capital at the San Francisco Liberation School led by Harry Chang, a Korean-American Marxist, brought together several future Rectification leaders and cadre. Another important connection was shared experience in the Venceremos Brigade, in which U.S. activists did voluntary labor in Cuba. Still others took part in the Racism Research Project (RRP), also led by Chang, which resulted in the widely read pamphlet Critique of the Black Nation Thesis (although Chang did not stay with the developing party-building movement).

Two other groups critical to the birth of the rectification network were the Union of Democratic Filipinos (KDP) and the Northern California Alliance (NCA). The KDP and NCA grew up alongside the New Communist Movement, but disdained the party-building efforts of the late 60s-early 70s as premature. (They also maintained support for Cuba and Vietnam, drew from those parties’ politics, and maintained ties with groups the New Communist Movement considered “revisionist” like the Puerto Rican Socialist Party and the Chilean MIR.)

KDP leaders had direct experience with the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), and saw that group’s party-building line, as summed up in Jose Maria Sison’s pamphlet “Rectify Errors and Rebuild the Party” as an updating of Lenin’s What is To Be Done? applicable to the U.S. KDP saw itself as a “revolutionary mass organization” with Marxist-Leninist leadership rather than a party, although their level of internal discipline rivaled any of the U.S. parties and “pre-parties.” NCA came from the MISO tendency (for “mass intermediate socialist organization”) which did political organizing in working class communities around local radical newspapers. The decision by some leaders of KDP and NCA to move from “mass organizing” with Marxist-Leninist leadership to party-building on the basis of line development led to a split in NCA. Meanwhile, KDP’s relations with the faction-ridden but still primarily Maoist CPP were strained.

Leading the initial effort to found the rectification network in December 1976 were KDP leaders Bruce Occeña and Melinda Paras and Max Elbaum, then a leader of the Northern California Alliance. Soon thereafter, Third World Women’s Alliance leader (TWWA) Linda Burnham joined the group. Believing that the organizational side of party building needed to be conducted mainly in secret, the network was initially clandestine and had no formal name, its members and supporters becoming known loosely as “rectificationists.”

In 1978, rectification leaders built close ties with two members of the Guardian staff – Executive Editor Irwin Silber and former Third World Women’s Alliance leader Frances Beal who were subsequently recruited into the rectification network. At their urging, other network members joined the just-being-formed Guardian Clubs. And Silber – who had authored many of the Guardian’s ideological polemics – began to propound key elements of the rectification perspective in his Guardian columns and in debates in the Club Network.

By late 1978 differences over the Clubs’ direction and the party-building line of the Guardian led to a split, with the Guardian Club membership – supported by Silber and Beal – breaking away to form the National Network of Marxist-Leninist Clubs (NNMLC) in March 1979. This new group enabled the rectificationists to go public and publish the first comprehensive statements of the rectification line. But as Max Elbaum notes, the NNMLC’s “public attacks on the Guardian were extremely harsh, as were its broad-stroke criticisms of the OCIC. This did not auger well for the Rectificationists’ capacity to establish friendly relations with communists who held differing views.”

In the spring of 1980 the rectification network began issuing a journal, Line of March, drawing on a phrase taken from the Communist Manifesto. The title immediately became the name commonly used for the rectification network as well. Line of March proceeded to produce theoretical materials targeting central premises of the New Communist Movement and the Communist Party of China: first, the thesis that capitalism was restored in the Soviet Union under Khrushchev and Brezhnev; second, the Comintern Black Nation thesis as basis for the analysis of racism in the U.S. and racial divisions in the U.S. working class.

Ideologically, the rectification tendency was initially dominated by the orthodoxy of the CPP, which was heavily influenced by Stalin and Mao. As Max Elbaum described them, “the central rectification activists considered themselves the most orthodox defenders of Leninism around”. For its strategic orientation, rectification rejected the “United Front Against Imperialism” line favored by many in the New Communist Movement and elaborated a strategy it termed the “United Front Against War and Racism.” Rectificationists initially saw the development of the “anti-revisionist, anti-dogmatist” trend as the basis for a rectified CP. However, with the collapse of the OCIC in 1980, Line of March turned toward the CPUSA and the Democratic Socialists of America as the potential core of a future United Front.

In its mass practice, Rectification targeted four social movement arenas for direct intervention: anti-racism, anti-imperialism, women’s liberation and labor. The National Anti-Racist Organizing Committee (NAROC) was formed on the basis of mid-1970s work organizing the National Coalition to Overturn the Bakke Decision. A Southern Africa Organizing Committee was formed (helping shift the focus of the solidarity movement from the former Portuguese colonies to the fight against apartheid), which later became a broader, national US Anti-Imperialist League (USAIL). However, USAIL’s ties with non-Line of March forces withered, and the group was re-christened the Peace and Solidarity Alliance (a public move away from the New Communist Movement’s shunning of rhetoric of “peace” and toward the Soviet goal of “peaceful coexistence” of the global camps). The TWWA was renamed the Alliance Against Women’s Oppression and focused on the struggle for reproductive rights, while attacking the predominant left force in that movement, socialist feminism. The NCA fragment that joined Line of March turned its attention to the labor movement. All four “revolutionary mass organizations” attempted to bring the United Front Against War and Racism proposal to the fore in their assigned movements, but had little success.

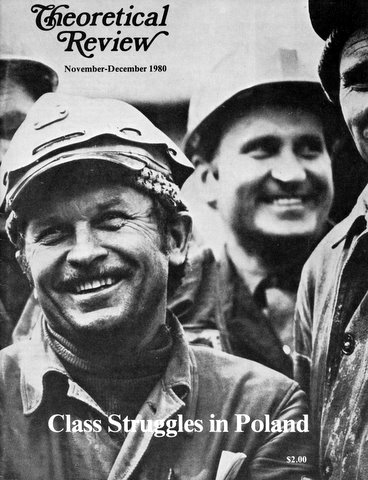

Rectification also launched the Marxist-Leninist Education Project (MLEP): classes for activists that drew on a Comintern-style distillation of Marxism-Leninism. MLEP launched critiques of Mao’s dialectics (which it considered an idealist backstep from Stalin’s Dialectical and Historical Materialism), dependency theory (the subject of a debate in the journal Latin American Perspectives), and Western Marxism (particularly Althusser and Poulantzas). Line of March also attempted to engage non-Trend intellectuals in debate on the crisis in Poland (specifically, Paul M. Sweezy of Monthly Review and Jonathan Aurthur of the Communist Labor Party). LOM’s own reputation reached its lowest point around that issue, when it supported the imposition of martial law in Poland against Lech Walesa’s Solidarity union movement.

A Critique of the Northern California Alliance

Harry Chang: A Seminal Theorist of Racial Justice by Bob Wing

Critique of the Black Nation Thesis by Harry Chang et al

We Are Revolution. A Reflective History of the Union of Democratic Filipinos (KDP) by Helen C. Toribio

Is the Red Flag Flying? The Political Economy of the Soviet Union by Albert Szymanski

A Joint Statement on the Party Building Line of the National Network of Marxist-Leninist Clubs by the Tucson and Boston Theoretical Review Editorial Boards

A Response by the National Network of Marxist-Leninist Clubs by Tim Patterson

Our Differences [Reply to Tim Patterson] by Paul Costello

The War in Indochina by Irwin Silber

Documents from the Founding Conference of the National Network of Marxist-Leninist Clubs

Rectification vs. Fusion. The Struggle Over Party Building Line

NNMLC Study Guide on Theoretical Review Party-Building Line

Marxism and the Crisis of Imperialism by the Line of March Editorial Board

U.S. Foreign Policy: A Turn Toward War by the Line of March Editorial Board

The 1980 Elections: Reaffirming the Marxist Theory of the State by the Line of March Editorial Board

The Theory and Practice of the Rectification Movement by Max Elbaum and Melinda Paras

Afghanistan: the battle line is drawn by Irwin Silber

Capitalism in the USSR? An Opportunist Theory in Disarray by Bruce Occeña and Irwin Silber

Dialectical or Mechanical Materialism (A Response) [to Clay Newlin] by The Marxist-Leninist Education Project Theory of Knowledge Group

[Back to top]

The Theoretical Review, which had been started by the Tucson Marxist-Leninist Collective (TMLC) in 1977, began publishing articles on party-building the following year. It soon began to rally other groups to its line – a Boston editorial board was created in 1979 which developed into the Boston Political Collective (Marxist-Leninist) (BPC (M-L)). Boston TR supporters had been active in the Boston Guardian Club in 1978, and both the TMLC and the BPC (M-L) participated in the Organizing Committee for an Ideological Center.

The TR’s party building line was called “primacy of theory.” This meant prioritizing the training of cadre and the development of Marxist-Leninist theory adequate to the challenges facing U.S. communists. Against the OCIC which advocated “fusing communism with the workers’ movement,” the TR replied that U.S. communists lacked an effective theoretical-political line and analysis to bring to this task. Against Line of March which prioritized developing a “rectified” general line for our movement, the TR replied that the trend lacked the theoretical tools necessary for this task as well.

Unlike other trend forces, the TR was highly critical of pre-1956 Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy. Likewise, while other trend forces generally welcomed developments in China following the death of Mao and the defeat of the Gang of Four, the TR viewed these developments as China’s departure from the revolutionary road.

TR forces used the journal to call attention to what it believed were creative developments in Marxist-Leninist theory and to apply its own interpretation of this theory to problems facing the trend. In particular, the TR paid attention to ideological and cultural issues and to questions of communist history.

NNMLC Study Guide on Theoretical Review Party-Building Line

An Introduction to Theoretical Practice

Primacy of Theory and the Guardian Clubs by the Red Boston Study Group

Defining the Central Task for Party Building

The Primacy of Theory and Political Line by the Tucson Marxist-Leninist Collective

Why We Must Leave the Guardian Club by Irene B., Ricky D. and Rich L.

Theoretical Aspects of Political Practice by Neil Eriksen-Schmidt

China’s Great Leap Backward – A Review; and “A Short Note on Deng Xiaoping and the Present Line of the CCP” by Harry Eastmarsh

Study Guide to the History of the World Communist Movement (21 Sessions) by the Tucson Marxist-Leninist Collective

Study Guide to the History of the Communist Party, USA (12 Sessions) by the Tucson Marxist-Leninist Collective

A Joint Statement on the Party Building Line of the National Network of Marxist-Leninist Clubs by the Tucson and Boston Theoretical Review Editorial Boards

Party Building: Our Aim is True (Questions and Answers) by Paul Costello

Anti-Revisionist Lessons for Party Building Today by Scott Robinson

A Response by the National Network of Marxist-Leninist Clubs by Tim Patterson

Our Differences [Reply to Tim Patterson] by Paul Costello

Leninist Politics and the Struggle Against Economism by Paul Costello

Points of Unity by the Boston Political Collective (Marxist-Leninist)

Analyzing China Since Mao’s Death by Harry Eastmarsh

Afghanistan: Anti-Imperialism and World Revolution by Paul Costello

Debate on Afghanistan by David Finkel and Paul Costello

Popular Culture and Revolutionary Theory: Understanding Punk Rock by Neil Eriksen

Class Struggles in Poland by Paul Costello

[Back to top]

The Bay Area Workers’ Organizing Committee (BAWOC) was one of a number of small Marxist-Leninist collectives that sprang up around the country in the late 1970s and which identified themselves with the anti-revisionist, anti-dogmatist Trend. As its name indicates, it was clearly influenced by the Philadelphia Workers Organizing Committee, and it initially it shared with PWOC the fusion party building line and an involvement in the Organizing Committee for an Ideological Center.

By 1980, however, the development within the Trend of alternative party building lines, namely Rectification, led by Line of March and Primacy of Theory, led by forces associated with the Theoretical Review journal, was giving rise to dissatisfaction with the fusion party building line in some of these circles.

This dissatisfaction crystallized in BAWOC in 1980 in the formation of a minority bloc which rejected fusion in favor of the Primacy of Theory line. Early that year both the BAWOC majority and the minority issued alternative draft Political Reports which demonstrated how local groups were seeking to interpret and apply the fusion line and the developing critique of it from the the Primacy of Theory perspective.

Some Notes on the Struggle Within BAWOC by JM

Political Report by the BAWOC Majority

Political Report by the BAWOC Minority

[Back to top]

The Split in the Milwaukee Alliance: A Struggle Against Empiricism

Our Unions: Where we’re at, Where we’re going

Comments on The OC’S First Year

[Back to top]