Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line

U.S. Anti-Revisionism

The New Communist Movement: The Early Groups, 1969-1974

The New Communist Movement emerged in the late 1960’s, as the civil rights and anti-Vietnam war movements became increasingly radicalized. Students and youth began to reject ’working within the system’ and lost faith in electoral politics and nonviolent tactics. These activists gravitated toward organizing in working class settings: workplaces, particularly factories; neighborhoods; community colleges, and military bases. Though many things helped trigger the emergence of a new movement of communists, four especially significant influences stand out:

– The Cuban Revolution, the Vietnamese struggle, and other national liberation movements helped many people see both the imperialist nature of U.S. global actions, and challenged a great deal of anti-communist mythology that had held the stage in the 1950s;

– The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China suddenly made it possible to think about a communist alternative to the model presented by the societies of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union;

– The Black liberation struggle in the U.S. relentlessly revealed the crimes of racism and class exploitation built into U.S. society, and tore away many naive notions of an America that was upwardly mobile, inherently just, and generally affluent;

– The radical uprisings of France in May 1968 suggested that revolution might not be for Third World countries alone, and that there were possibilities, in some situations, for large numbers of people to collaborate (even in countries like the U.S.) in a genuinely revolutionary project.

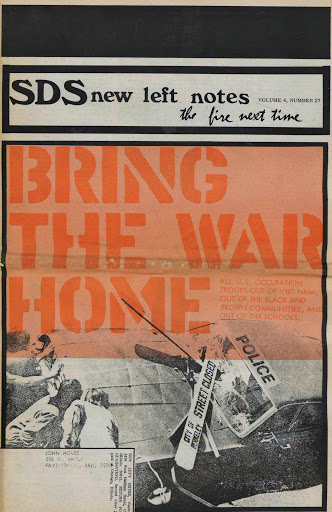

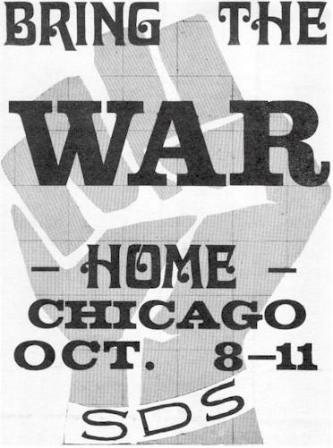

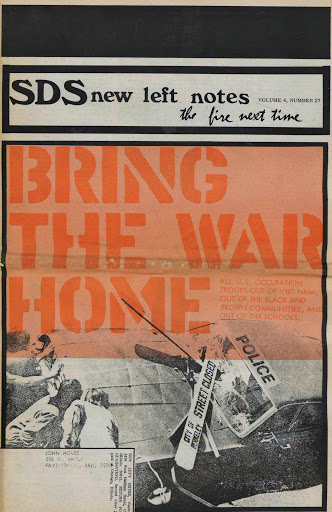

Many of the first recruits to the New Communist Movement came from Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the largest New Left organization of white students in the country from 1965 to 1969. These SDS members discovered Marxism, often through the efforts of the Progressive Labor Party (PL) [for PL’s background and documents, see “Progressive Labor Movement”], or in the course of advancing New Left theory and practice.

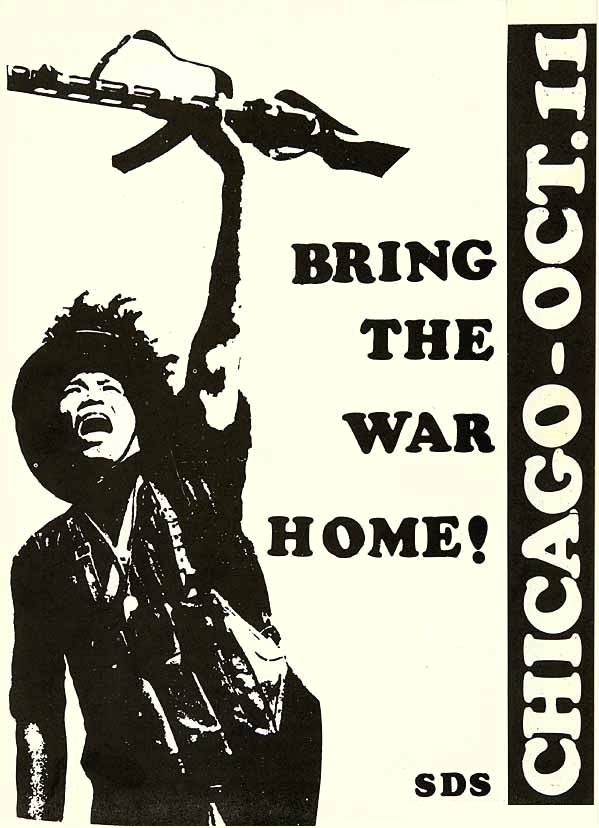

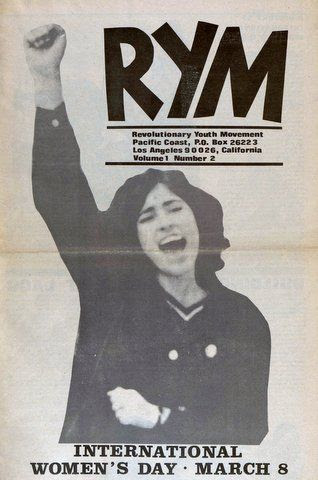

As SDS entered a period of crisis in the late 1960’s, two Revolutionary Youth Movement currents (RYM) emerged as alternatives to PL. RYM I (better known as Weatherman) adopted a politics that increasingly saw white people generally as bought off and therefore likely to be in the enemy camp of the ongoing global collisions. A diverse opposing camp, RYM II, identified with working class organizing, disciplined forms of left organization, and Marxism-Leninism, but rejected what it saw as PL’s sectarianism, anti-nationalism, and “more revolutionary than thou” stance toward everyone from the Black Panther Party to the NLF of South Vietnam. RYM II saw in this alternative synthesis the potential for creating a revolutionary sector among white workers and a revolutionary movement rooted in the larger multinational working class. RYM II was the source of some of the first New Communist Movement groups.

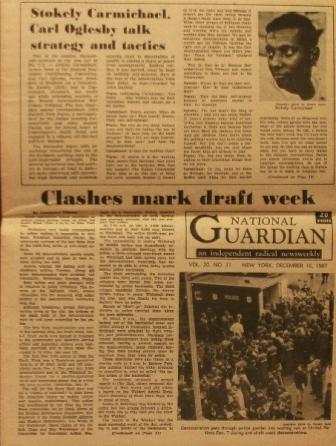

But quite a few other recruits to the New Communist Movement came from radical student groups active among Black, Puerto Rican, Asian and Chicano students. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) produced circles of trained organizers who played an important role in the creation of new communist organizations. And a few older veterans of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and earlier anti-revisionist formations like the Provisional Organizing Committee (POC) [for the POC’s background and documents, see “The Second Wave of US Anti-Revisionism, The Provisional Organizing Committee (1956-1962)”], played a mentor role within that process – often hoping to create organizations modeled on earlier stages of the CPUSA, which, in their view had once been more revolutionary, but had been betrayed by political changes over the 1950s.

New Communist Movement groups in the U.S. shared the following characteristics. They:

· identified themselves as coming out of the Marxist-Leninist tradition of the Bolshevik Revolution, the Comintern, and the international Communist movement;

· rejected the Trotskyist strain within that tradition;

· upheld the vanguard role of the proletariat in the fight for socialism, rejecting alternative theories of student or other, non-proletarian vanguards;

· rejected modern revisionism in its theoretical, political, ideological and organizational forms;

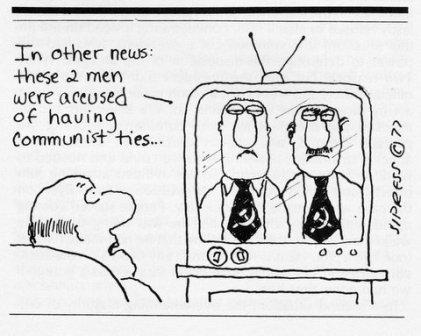

· denied the leading role of the CPSU internationally and of the CPUSA nationally as revisionist betrayers of revolutionary Marxism-Leninism;

· They were committed to the creation of a new, non-revisionist, revolutionary Marxist-Leninist communist party, proletarian revolution, and the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat in the U.S.

The most important of the early New Communist Movement organizations were the Communist League (CL), the Revolutionary Union (RU) and the October League (ML) (OL). Each group had ties to the New Left, but only CL had roots in earlier anti-revisionism: among its founders were expelled members of the POC in California led by Nelson Peery.

RU began as the Bay Area Revolutionary Union in 1968, and closely identified itself with Mao and the People’s Republic of China. Its origins were similar to numerous working-class organizing ’collectives’ that formed in industrial areas across the US in the wake of SDS collapse which later turned to Marxism-Leninism.

The OL formed from the merger of two collectives led by former leaders of SDS’s RYM II faction. The Georgia Communist League (ML) in Atlanta and the October League in Los Angeles were more focused on studying revolutionary doctrine than the early RU, but shared its determination to become a real force among local workers.

Distinct among early New Communist Movement organizations was the American Communist Workers Movement (Marxist-Leninist). This group, which had its origins in draft resistance and student activism in Cleveland, early on closely identified itself with an international anti-revisionist tendency organized by Hardial Bains, which had previously created anti-revisionist Communist organizations in Canada, Ireland and the United Kingdom.

All of these groups shared a common commitment to building a new multinational, cadre-based vanguard communist party with deep political ties in the working class and oppressed communities.

At the same time, in Chicago, another collective with Marxist politics, a working-class orientation and national ambitions formed out of RYM II: the Sojourner Truth Organization (STO). The early STO had many points in common with the New Communist Movement, but quickly moved in a more unorthodox direction. It began to identify more with post-1968 European revolutionary groups who advocated self-motivated actions by workers such as wildcat strikes and plant takeovers, and alternative-union formations. STO collaborated with like-minded collectives such as Harper’s Ferry Organization in New York City and Worker Unity Organization in St. Louis.

Background Materials

General Surveys

A Critical History of the New Communist Movement, 1969-1979 by Paul Costello

Family Tree Chart of U.S. Anti-Revisionism, 1956-1977 by the Communist Workers Group (Marxist-Leninist)

Maoism in the United States by Max Elbaum

Turn to the Working Class: The New Left, Black Liberation, and the U.S. Labor Movement (1967-1981) by Kieran Walsh Taylor

Black Like Mao: Red China and Black Revolution by Robin D.G. Kelley and Betsy Esch

“Concrete Analysis of Concrete Conditions”: A Study of the Relationship between the Black Panther Party and Maoism by Chao Ren

What Legacy from the Radical Internationalism of 1968? by Max Elbaum

General Primary Materials

American Maoism: Re-emergence and Regroupment by Jon Hillson, Denver Branch, Socialist Workers Party

The History and Present State of the Contemporary Revolutionary Movement in the U.S. by People’s Democracy

Some Lessons from the Family Tree of the New Communist Movement by Dennis O’Neil

Response to Dennis O’Neil by Max Elbaum

Response to Max Elbaum by Dennis O’Neil

Second Response to Dennis O’Neil by Max Elbaum

SDS and RYM II: Antecedents of the New Communist Movement

SDS Split, 1969

PLP: A Critique [published by Old Mole] newspaper

Looking Back and Looking Ahead at Revolutionary Youth Movement by Michael Klonsky

Old Left Orthodoxy – Impediment to Revolutionary Progress? [On PL vs. RYM]

Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh, the NLF is gonna win! by Bernardine Dohrn, SDS Inter-Organizational Secretary

The White Question by Mike Klonsky, SDS National Secretary

Metamorphosis in S.D.S. The New Left is Showing Its Age by Thomas R. Brooks [New York Times, June 15, 1969]

Black liberation and peace debated by SDS by Lincoln Webster Sheffield

Letter from S.D.S. Leadership

Statement on the Walk-Out [PL Statement on the SDS split]

National Secretary’s Report: RYM Walks Out [PL’s Analysis of the SDS split]

Thoughts on the SDS convention by Lincoln Webster Sheffield

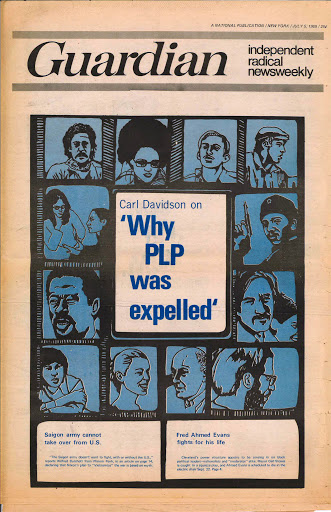

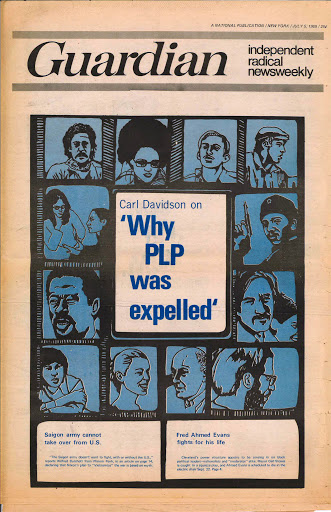

SDS ousts PLP by Jack A. Smith

PL declares split, elects ’SDS’ officers by R.F., Guardian staff correspondent

The ’worker student alliance’ by Randy Furst, Guardian staff correspondent

SDS Deals with the woman question by Margie Stamberg, Guardian staff correspondent

The Real SDS Stands Up by Andrew Kopkind [Hard Times, June 30, 1969]

SDS Convention Split: Three Factions Emerge

The split at the SDS national convention by Mary-Alice Waters

Why SDS Expelled PL by Carl Davidson

Expulsion [Guardian Editorial]

SDS National Convention by Allen Young [Great Speckled Bird]

Education Secretary’s Report: The Boston Strangler: A Paper Tiger by Bill Ayers

The press views SDS at its national convention

SDS and PL differ on the national question by Carl Davidson

SDS [split in Atlanta, Georgia] [Great Speckled Bird, July 21, 1969]

SDS Expels PL [RYM Statement on the SDS split]

Spartacist Special Issue on the SDS Split: New Left’s Death Agony

“You’re Either Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution” [The Movement, Vol. 5 No. 7, August 1969]

Forward or backward? [Guardian Editorial on Weathermen and RYM-2]

SDS and the Movement: Where Do We Go From Here? by Jack Weinberg and Jack Gerson [on the SDS split, PL, RYM II, RU]

The SDS’s Desolation Row by Jack Gerson [On RU, Weatherman, PL, and RYM II]

Two, Three, Many SDS’s by Lenny Glynn

Who Are the Bombers? Often the Rulers! by SDS [PL]

SDS Split, 1969, at the local level – Stanford SDS

Radicals Convene. Views Differ In SDS National by Karen Davidson

SDS Position Clarified by Leonard Siegel

Progressive Labor Party: ’All Nationalism Is Reactionary’ by T. H. Andre

Re-Reassessments: What Is Nationalism? by Ivo Banac

Re-Reassessments: Domestic Capitalism by Ivo Banac

Factions Split SDS Meeting In Vicious Shouting Match by Richard Embry

In Search Of The ’Real S.D.S.’ Favoring A Campus Worker-Student Alliance by Doug Hogan

A Letter In Reply by members of RU

WSA And PLP Repudiate Revisionism by Ivo Banac

’New’ SDS Chapter Formed From Split by Richard Embry

Revolutionary Youth Movement II

Debate within SDS. RYM II vs. Weatherman

5 proposed principles of SDS unity

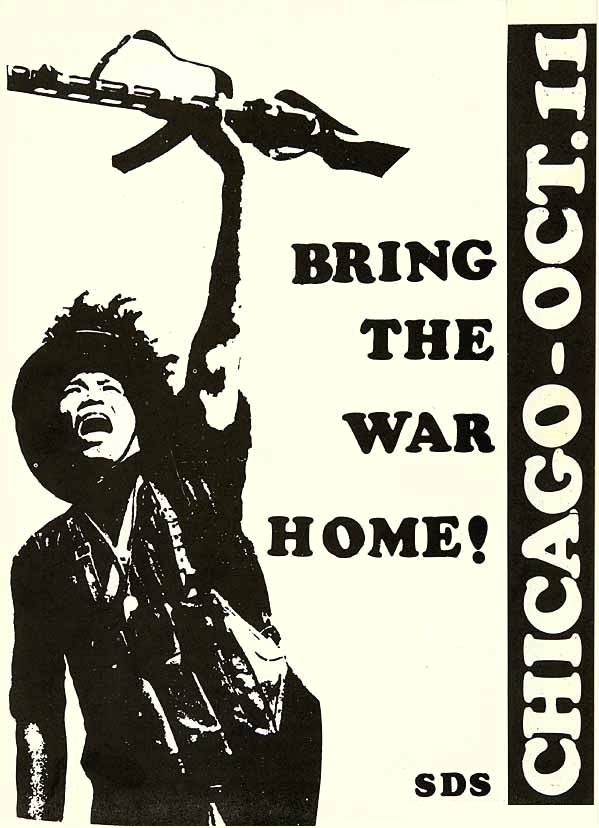

Take the War to the People

RYM-2 meets

A Call to All Proletarian Youth and Proletarian Organizations

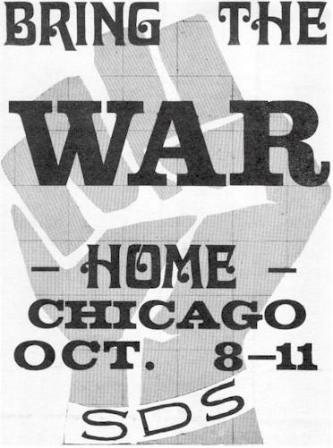

Gettin’ It On! – Call to National Action

October Anti-War Actions: Three Views [The Rag, September 29, 1969]

RYM Conference: Women Unite! by Sally Gabb et al [Great Speckled Bird, December 8, 1969]

Toward Mass Action by Bob Goodman [Great Speckled Bird, December 8, 1969]

Grym Too by Steve Wise [Great Speckled Bird, December 15, 1969]

Women lead founding of RYM by Carl Davidson

Why We Carry the N.L.F. Flag! [RYM II leaflet]

Maoism vs. National Liberation: Where Does RYM II Stand?

Periodical

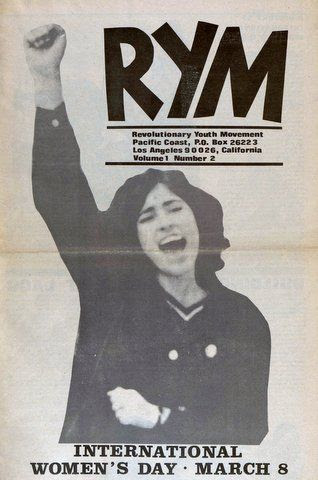

Revolutionary Youth Movement newspaper [No. 1]

RYM newspaper [No. 2]

The Beginnings of a New Communist Movement

The Movement and the Workers by Clayton Van Lydegraf

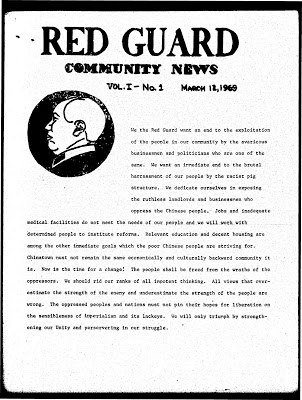

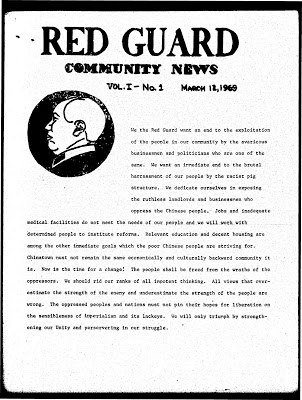

The Battle of People’s Park by the Red Guard Caucus, Berkeley SDS

Unite Theory with Practice To Build A Communist Party! by Bill Epton

Which Side Are You On? [on the theory of the “new working class”] by Carl Davidson

The Black Liberation Struggle (within the current world struggle) by Bill Epton

[Back to top]

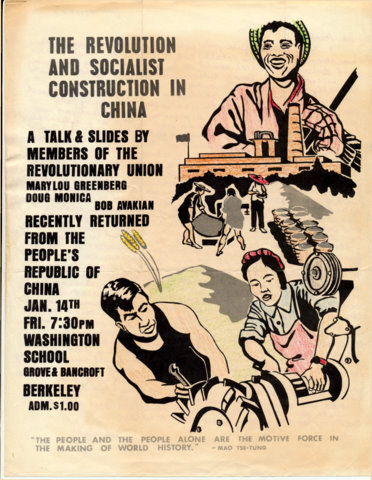

Bay Area Revolutionary Union – Revolutionary Union

The Bay Area Revolutionary Union (BARU) began in 1968 as a working class organizing collective based in the San Francisco Bay Area, mainly in the East Bay region which includes Oakland, Berkeley, Richmond, San Jose and Palo Alto. BARU was inspired by the Oakland-based Black Panther Party, whose newspaper, “The Black Panther,” brought Marxist ideas to a larger working class audience than any group since the heyday of the Communist Party USA. BARU identified more strongly with Marxism-Leninism Mao Zedong Thought than the Panthers did, and soon developed a separate outlook and strategy.

At its inception, BARU emphasized “building the workers’ movement” over “party building.” It took part in a petroleum workers’ strike in Richmond in 1969, organized working class youth groups, and did campus organizing at Stanford University and other schools. By circulating its “Red Papers” series of collected position papers nationally, it connected with activist collectives in cities across the U.S., as well as influenced the broader developing New Communist Movement.

In the summer of 1970, the BARU followed up on the connections it had made through Red Papers with a national tour which helped it cement relations with some of these collectives. In the wake of this national tour, new RU collectives developed in a number of areas and the national office was moved to Chicago.

The RU underwent a major internal split in 1970-71 with a section (which became the Venceremos Organization) that had advocated more openly violent tactics and a pan-Third World emphasis. In the ensuing polemic the RU moved away from the view that a paramilitary uprising was imminent – the stance of the early Black Panther Party – and toward a more traditional communist approach of long-term organizing with the goals of building a new revolutionary party and eventually a mass revolutionary working class.

Historical Works

Summation of Experience in Revolutionary Union and Bay Area Communist Union by Steve Hamilton

On the History of the Revolutionary Union (part one) by Steve Hamilton

On the History of the Revolutionary Union (part two) by Steve Hamilton

Ambush at Keystone No. 1: Inside the Coal Miners’ Great Gas Protest of 1974 [on RU work in the coalfields] by Mike Ely

Prairie Fire: Rock Maoists by Mat Callahan

Primary Background Documents

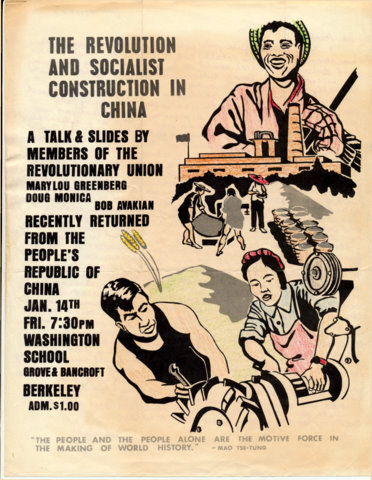

Panther shootout – whose game was it? by Robert Avakian

Oil! Avakian Bust

Radicals Convene. Views Differ In SDS National by Karen Davidson

Union of Revolutionary Women by Mary Lou Greenberg

In Search Of The ’Real S.D.S.’ Favoring A Campus Worker-Student Alliance by Doug Hogan

A Letter In Reply by members of RU

WSA And PLP Repudiate Revisionism by Ivo Banac

Student Retires After Week’s Stint As FBI Informer On RU Activities by “Ron Goldstein”

Revolutionary Union Splits Over Differences In Ideology, Tactics by Bill Evers

Internal Security Investigation: Venceremos Cited In House Report by Glenn Garvin

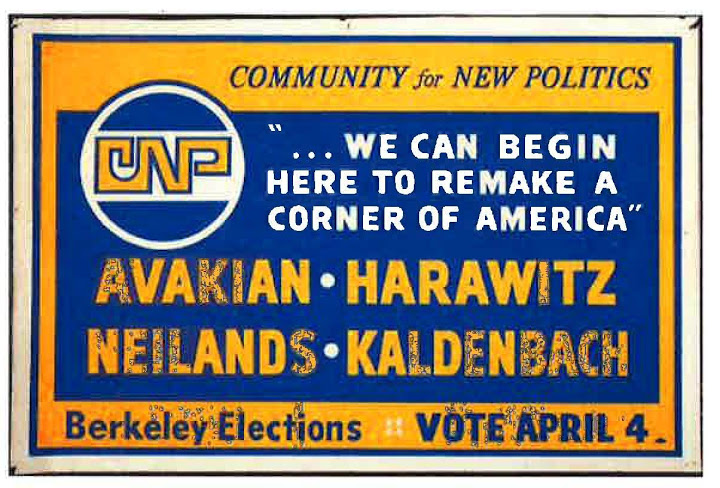

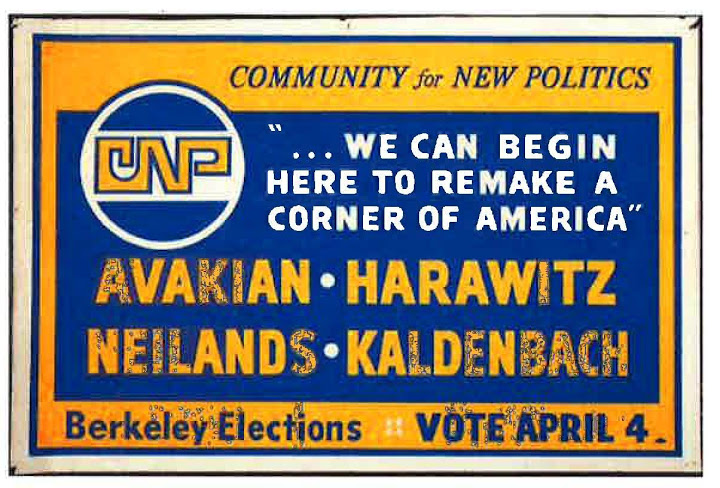

Bob Avakian Before RU

Progressive Labor Critique of Scheer Race

’Schmeer’ Cop Report Refused By Council

Nary A No Among Our City’s Heads

CNP To Boost Student Power

CNP: Up from Liberalism by Bob Avakian

Socialist Election Campaign in Berkeley by Brian Shannon [Young Socialist, February-March 1967]

Berkeley Barb Editorial: To Vote Right, Tip Left

Right Wins Listless Battle

Lauds Gunrunning as Valid Alliance

Berkeleyans on Way to NCNP Convention

FSM Funds May Help Black Rebel Groups

Mea Culpa Mea Culpa

New Politics: Meanwhile, Back at the Boondocks... by Lee Felsenten

Factions Forming in New Peace Party?

Panthers & Radicals

To the Bastille

PFM’s Second Wind

Stokely Here Soon

Caucus Calculations on Cleaver and Rubin

Critiques and Polemics

Letter to RU Executive Committee by the Los Angeles RYM II

1969 Richmond Oil Strike–An Analysis [from Progressive Labor magazine]

How the Revolutionary Union Renders Lenin More Profound While Aiding the CPUSA [from the Communist League’s Proletariat]

The United Front against Imperialism? by the Sojourner Truth Organization

A Critique of the United Front against Imperialism as a Strategy for Revolution within the U.S. by the Commentator Collective

The national question in the U.S. today [review of Red Papers 5] by Carl Davidson

Debate on the national question [reply to Davidson’s review of Red Papers 5] by the Revolutionary Union

The Revolutionary Union by Workers Vanguard

SLA Action: Some People Jump Under The Bed by the Revolutionary Union

Which Side Are You On? [on RU and the SLA] by Carl Davidson

International Women’s Day Sparks Two Line Struggle by the Revolutionary Union

Which Side Are You On? [on RU and women’s emancipation] by Carl Davidson

Revolutionary Union: Opportunism in a “Super-Revolutionary” Disguise by the October League (M-L)

Marxism or American Pragmatism? The Right Opportunist Line of the R.U. by Workers Viewpoint Organization

RU’s Errors: “Leftism”

Some Notes on the Revolutionary Union by Gordon Fox [Young Socialist Discussion Bulletin, Vol. 18, No. 8, December 1974]

The Struggle Within: A Critique of the Role of the Revolutionary Union within the USCPFA by the U.S.-China Peoples Friendship Association of Detroit

Red Papers 7: Revolutionary Union’s “United Front” with NATO by Young Spartacus

Critique of Red Papers 7: Metaphysics Cannot Defeat Revisionism by Martin Nicolaus

PRIMARY DOCUMENTS

Red Papers

Red Papers 1

Red Papers 2

Red Papers 3: Women Fight for Liberation

Red Papers 4: Proletarian Revolution vs. Revolutionary Adventurism: Major documents from an ideological struggle in the Revolutionary Union

Red Papers 5: National Liberation and Proletarian Revolution in the U.S.

Red Papers 6: Build the Leadership of the Proletariat and Its Party

Red Papers 7: How Capitalism has been Restored in the Soviet Union and What This Means for the World Struggle

Other Primary Documents

The “New Economic Policy”

They’re In For Us, We’re Out for Them

China’s Foreign Policy: A Leninist Policy

Unite the People, Defeat Our Enemies. Statement by the Revolutionary Union on the Shooting of George Wallace

Classes and Class Struggle

Proletarian Dictatorship Vs Bourgeois “Democracy”

How Socialism Wipes Out Exploitation

Union Drive in the Southwest: Chicanos Strike at Farah

On Building the Party of the U.S. Working Class and the Struggle Against Dogmatism and Reformism: Speeches by Bob Avakian

Work Among Students and Youth

Build the Anti-Imperialist Student Movement

Capitalism in Crisis – Fight for a Decent Education!

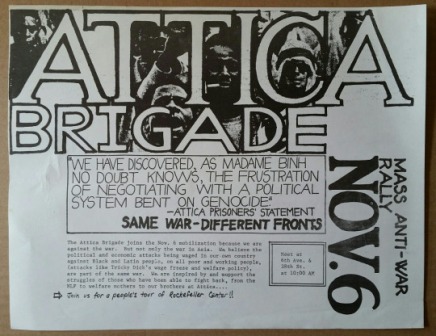

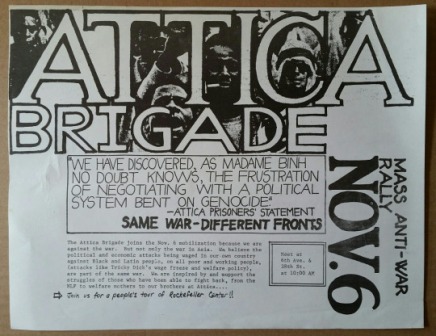

Audio Recording of Tim Devine and Shelly Bogen at Illinois State University on the work of the Revolutionary Union and the Attica Brigade [part 1], [part 2], [part 3: questions from the audience] (1973)

Transcript of Tim Devine and Shelly Bogen presentation at Illinois State University on the work of the Revolutionary Union and the Attica Brigade [part 1], [part 2], [part 3: questions from the audience] (1973)

Attica Brigade

Attica Brigade

200 Attend Regional Meeting of Attica Brigade on Campus

The Time is Now.... [call to a National Convention]

The Time is Now.... [letter to Guardian subscribers about the upcoming National Convention]

Editorial: The Road Ahead

Revolutionary Student Brigade

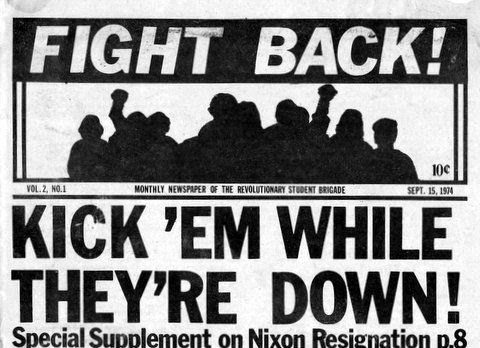

Revolutionary Student Brigade

’Revolutionary Student Brigade’ formed in Iowa by Ben Bedell

Opinion: Revolutionary Students by Members of the Revolutionary Student Brigade

Surreally Political by Arn Passman, [Berkeley Barb, August 16-22, 1974]

National Convention Launches RSB

The Bums Are On the Run – Kick ’Em While They’re Down!

“Revolutionary” Student Brigade Holds Conference: Maoists Exhume New Left by Young Spartacus

R.S.B. Internal Newsletter, No. 1

R.S.B. Internal Newsletter, No. 2

Revolutionary Student Brigade Tour Through the Southwest

Seize the Times! Internal Newsletter of the Revolutionary Student Brigade, #10, February 25, 1975]

US and USSR Grab for Angola

[Back to top]

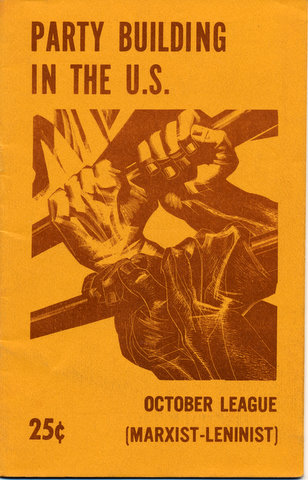

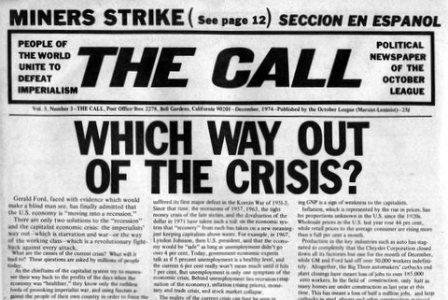

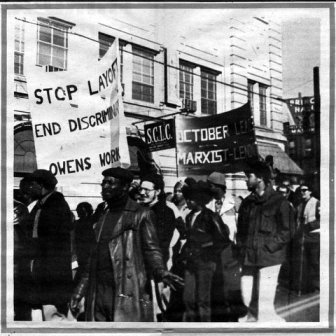

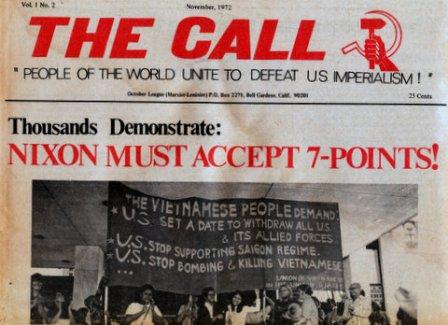

The October League (Marxist-Leninist)

The October League (Marxist-Leninist) originated directly out of the three-way debate that ended Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in 1969. The SDS faction RYM II opposed Progressive Labor and the Weatherman faction with a pro-worker organizing approach (unlike Weatherman) while supporting the Black Panther Party and other left-wing nationalist movements in communities of color (unlike PL). From the start, RYM II took a strong pro-China position, which had been PL’s hallmark until the latter group broke its ties to China in 1970. After the SDS break-up, RYM II became a national organization, Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM), but it soon disintegrated.

The Georgia Communist League (ML) (GCL) and the October League (Marxist-Leninist) (OL) developed out of the Atlanta and Los Angeles RYM collectives respectively. The Atlanta SDS-RYM collective had significant roots in a pro-RYM faction that had developed in SDS’s sister organization in the South, the Southern Student Organizing Committee, whose leader was Lyn Wells.

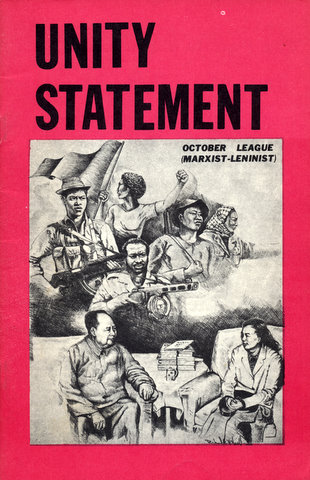

The OL and the GCL merged in 1971, and the national October League (ML) became the second largest group in the New Communist Movement, after the Revolutionary Union. The direction and strength of OL was shaped in part by their competition with RU over recruits and positioning in the broader left and progressive movements.

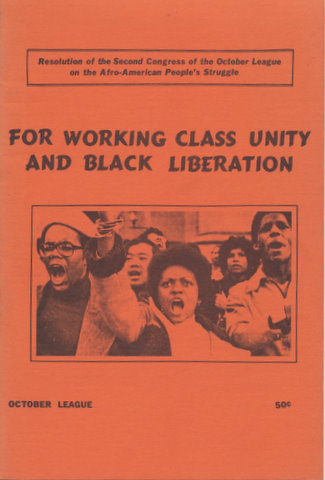

At first OL set a more orthodox course than RU – stressing party-building and opposing reforms like the feminist movement’s Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). Their literature bristled with hammers and sickles. They also hewed more literally to the CPUSA’s Stalin-era “Afro-American nation in the Black Belt” theory, which held that self-determination in the historic plantation area of the Deep South remained at the heart of African American people’s struggle for liberation.

In this period, OL saw ’ultra-leftism’ as the main danger in the party building process, which reflected its own efforts to tone down some of the rather alienating jargon and over-the-top symbolism that had been part of the culture of its founding collectives. OL soon found itself in a strategic position in a local wildcat strike at Mead Packaging in Atlanta. From that experience they toured the country arguing that an openly Marxist-Leninist group could offer leadership to militant workers.

By 1973, OL took on a more moderate persona, emphasizing accessibility to other left groups and a greater openness to popular reforms; for example, it reversed itself on ERA as the RU turned to a more hardcore ‘workerist’ position. OL absorbed several local collectives and fielded cadres into industrial jobs. In Detroit, it gained influence in the UAW Brotherhood Caucus. Within the burgeoning New Communist Movement, in this period, OL attempted to mark off a political space that combined loyalty to China with a stance reminiscent of the Comintern’s early Popular Front period.

Historical Works

Building Revolution in the South: The Southern Conference Educational Fund and the New Communist Movement, 1968-1981 by Doug Michel

Strike Fever: Labor Unrest, Civil Rights and the Left in Atlanta 1972 by Monica Waugh-Benton

Primary Background Documents

The family: obsolete or revolutionary? by Michael Klonsky

Communists meet to discuss labor by Rod Such

The Relationship Between the Struggle for Democracy and the Struggle for Socialism by Barry Litt

Critiques and Polemics

The October League by the Spartacist League

Iranian Communist Hits OL

The Struggle of Small and Medium-sized Nations by the October League

CL Replies to Attack by the Communist League

Primary Documents

Georgia Communist League (Marxist-Leninist)

An Introduction to the Red Worker

Attica: Tragic or Heroic

PL Launches Cowardly Attack [Nixon in China]

Georgia Communist League Statement on the Bombing of the Great Speckled Bird [Great Speckled Bird, May 15, 1972]

New Coalition [Great Speckled Bird, May 22, 1972]

California and Georgia Communists Merge

Periodical

The Red Worker

October League (Marxist-Leninist)

Statement of Political Unity of the October League (ML)

Women Hold Up Half the Sky

The Mead Strike

Mead Workers Caucus Recognized [Great Speckled Bird, September 18, 1972]

Atlanta wildcat strike ends

October League and Mead [Great Speckled Bird, October 16, 1972]

“Communist Inspired Strike?” October League press release

Interview: Mead Strike Leader

“Wildcat at Mead“ – A short film by the October League (Marxist-Leninist) (1972)

* * *

Atlanta Coordinating Committee

Atlanta Coordinating Committee [Great Speckled Bird, May 29, 1972]

People of the World Unite! Defeat U.S. Imperialism! [Great Speckled Bird, November 20, 1972]

APAC-ACC Rally [Great Speckled Bird, November 27, 1972]

* * *

UNITY: Rising Trend in the Communist Movement – Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization

Editorial: Lesson of Elections Build the Mass Movement

Revisionists launch new attacks

What is the October League?

Communists Call Labor Conference

Communist Work in the Factories: A Report on the Atlanta Conference [The Call Special Supplement]

Plant organizers meet in Atlanta [from the Guardian]

Building a New Communist Party in the U.S.

October League Expands Work

The Call Grows Louder

Watergate and the Fascist Threat

Role of Women’s Movement Debated at Guardian Forum

The October League’s Second Congress

Unified and Strong: October League Holds 2nd Congress

For Working Class Unity and Black Liberation

* * *

Editorial: Sectarian Attack at Guardian Forum

Healey Split Exposes Revisionist CPUSA

Call Seller Busted [Great Speckled Bird, September 3, 1973]

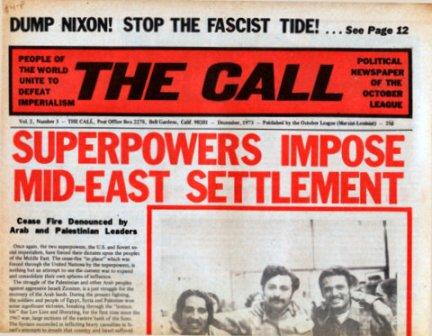

Editorial: Dump Nixon! Stop the Fascist Tide!

Sham Congress Called by Communist League

Bay Area Forum Hits “Social Imperialism, Revisionism”

OL Holds Second Labor Conference

Communists and the Present Crisis [Special Call Supplement on OL’s second labor conference]

Communist Unity: Three Groups Join Forces

Who Are the Real Terrorists? [on the Symbionese Liberation Army]

A United Front in the U.S.?

The Future is Bright: A Response to the Communist League

CPUSA tries to Glorify Imperialism

October League Holds Afro-American Conference

October League Holds Southern Labor Conference

Report from Labor Conference workshop: Organizing the Unorganized

Lessons Drawn from Building U.A.W. Caucus

Building a Revolutionary Student Movement, Part 1–SNCC and the Early Period

Building a Revolutionary Student Movement, Part 2–Students Against Imperialism

The Call Begins Third Year

Communists Reach Unity: October League Merges with ROAAW

Stop Boston Racist Attacks, Defend Right of Self-Determination by the October League (Marxist-Leninist)

March against Racism: Join Fred Hampton Contingent

Revolutionary Union: Opportunism in a “Super-Revolutionary” Disguise

[Back to top]

Black Workers Congress

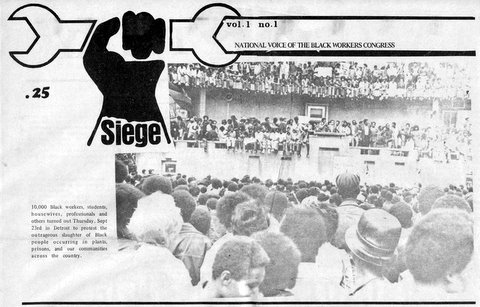

The Black Workers Congress (BWC) began as an attempt by some of the leaders of the Detroit-area League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW) to expand their efforts nationwide and connect with broader networks of working class-focused black activists. Present at its founding in December 1970 were, in addition to the LRBW, representatives from the United Black Brothers in Newark, union caucuses in Baltimore, Milwaukee, Chicago, Cleveland and Gary, Indiana, and former members of SNCC and the Black Panther Party.

The birth of the BWC marked the end of the LRBW, with one leadership group seeking to build the BWC as a separate formation, and the other deciding to merge with the Communist League, a multiracial group based in Los Angeles. [For more on the LRBW, see “The League of Revolutionary Black Workers”] The BWC, which began as an effort to build a new black community-centered working class revolutionary group, became a predominantly, but not exclusively, black contingent of the Mao-oriented New Communist Movement.

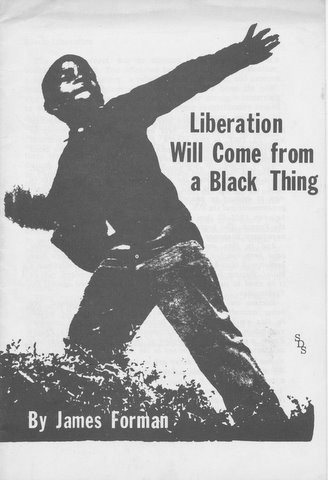

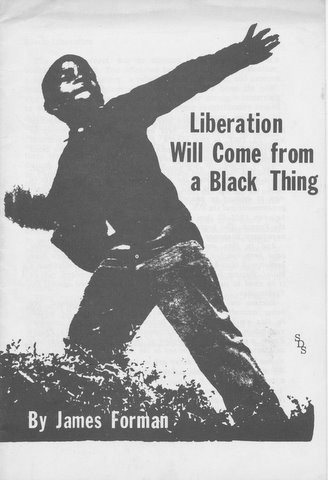

Like the LRBW, the BWC initially sought to bring revolutionary nationalist leadership to industrial workplace settings, in contrast to the Black Panther Party, which focused on youth and the poor in inner-city neighborhoods. But in the 1970’s, the influence of nationalism among the most militant black activists waned, replaced by a more focused interest in Marxist theory. The BWC moved from an eclectic grounding in thinkers such as Malcolm X, C.L.R. James, James Boggs, James Forman and Franz Fanon as well as the Marxist classics, to a rigid identification with orthodox Marxism-Leninism.

By 1973, the BWC had plunged into party-building discussions with other NCM groups, including the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization (formed out of the Young Lords Party, a New York-based cadre group with ties to the Black Panther Party), I Wor Kuen (a predominantly Chinese-American group in San Francisco and New York), and the mostly-white Revolutionary Union and October League. Unable to maintain internal stability, the BWC split into four divergent groups in 1975, breaking their ties to the group’s original mission and to each other.

Historical Works

BWC leader looks at past, sees new stage of struggle

History of the Modern Black Liberation Movement and the Black Workers Congress Summed-Up

Primary Background Material

Liberation Will Come from a Black Thing by James Forman

Primary Documents

DRAFT PROPOSAL: Manifesto of the International Black Workers Congress

Manifesto of the Black Workers Congress

CONTROL, CONFLICT AND CHANGE: The Underlying Concepts of the Black Manifesto by James Forman

300 Attend National Conference

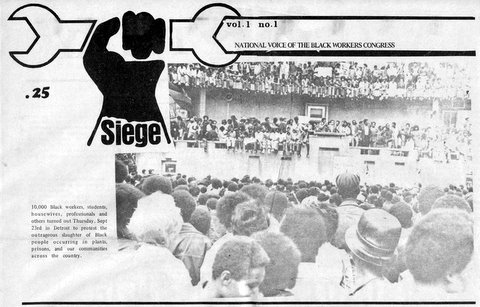

Siege, Vol. 1, No. 1 [1971]

Class Struggle and the Black Liberation Struggle: Who Will Lead?

Black America: Organize and Struggle by James Forman

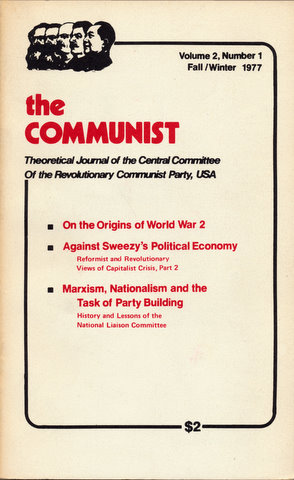

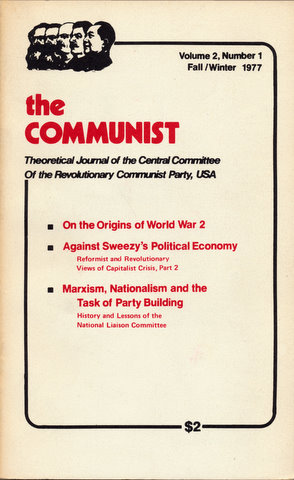

The Communist, Vol. 1, No. 1, August 15, 1974

Two-Line Struggle in the B.W.C.

Public Letter on Don Williams

[Back to top]

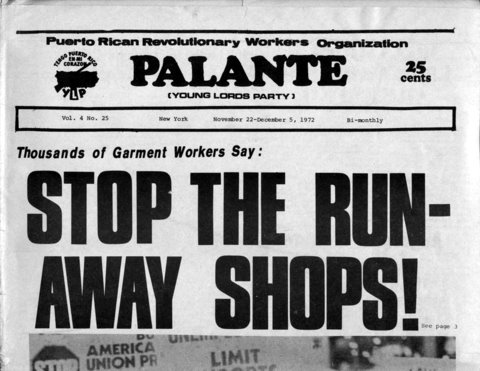

The Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization

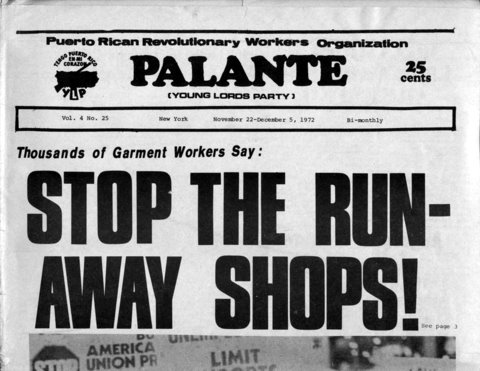

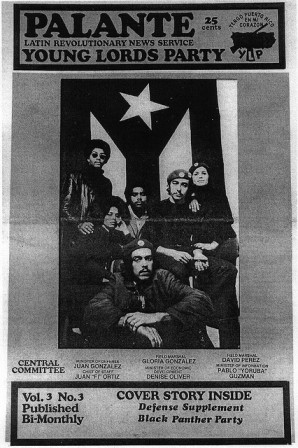

The Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization (PRRWO) was the name adopted by the former Young Lords Party (YLP), a mass revolutionary party of Puerto Ricans in the United States, in 1972. Inspired by the Black Panther Party and a Chicago Puerto Rican street gang that was politicized in the late 1960s called the Young Lords, the Young Lords Party was founded by a group of mostly Puerto Rican students from SUNY-Old Westbury, Queens College and Columbia University in 1969. Through community-based revolutionary organizing and popular mass actions, the YLP quickly became a significant force in New York’s Puerto Rican community and among city revolutionary activists as a whole.

The YLP promoted a “divided nation” theory about Puerto Ricans, seeing the Puerto Rican nation as having two concentrations (the island itself and the major Puerto Rican communities in U.S. urban areas) and Puerto Ricans within the U.S. as an integral and important part of the oppressed colonial nation and its independence struggle. The YLP also recognized the multi-racial character of Puerto Rican nationality and thought of itself as a multi-racial organization, building ties to U.S. black liberation movements and opposing racism in the Puerto Rican community.

In the early 1970s, as the mass movements characteristic of the 1960s began to ebb within the U.S., the YLP attempted to address the new conjuncture, first, by trying to implant a branch of their organization in Puerto Rico itself and second, by attempting to adopt more explicitly communist politics and organization. This shift was publicly initiated at their 1972 Congress at which the YLP became the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization, an explicitly Marxist-Leninist group. At this Congress, PRRWO committed itself to the long-term goal of building a new communist party and agreed to form a National Liaison Committee (NLC) together with the Revolutionary Union, Black Workers Congress and I Wor Kuen toward that end. (PRRWO’s involvement in the NLC and other Party building campaigns in the mid-1970s are covered in the next section of EROL – The New Communist Movement: Initial Party-Building Campaigns, 1973-1974).

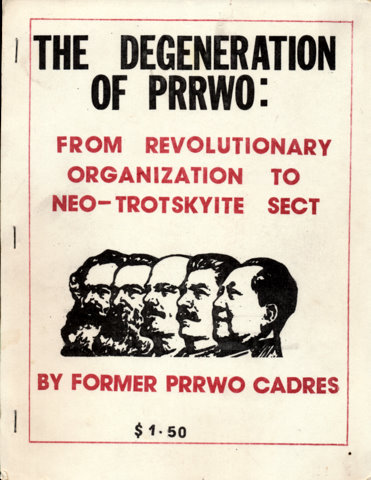

PRRWO’s changes in politics and organization were an attempt to solve problems that were, in fact, caused by the collapse of the mass movement of the 60s. They were accompanied by a growing belief by some within the PRRWO leadership that the problem within their organization was the result of deviations from communist orthodoxy. Their quest for a purer and more orthodox Marxism-Leninism led them back in time (past Maoism) toward an early communist ideology (which was progressively codified during the 1920s and 1930s by the Comintern as a militantly closed orthodoxy). In line with this process, a newly emerging PRRWO leadership embraced the view that repeated purges would strengthen the organization’s correctness and therefore guarantee its future success.

In reality, the organization (and its allied groups within the Revolutionary Wing configuration) became increasingly absorbed in bitter internal fighting over ideological matters that rapidly ate away their remaining membership, influence and political impact (these later developments will be covered in subsequent sections of EROL).

Historical Works

The Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization. A Staff Study

From Gang-bangers to Urban Revolutionaries: The Young Lords of Chicago by Judson Jeffries

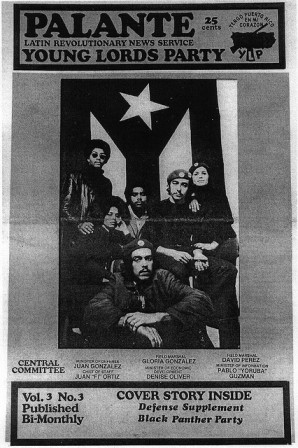

Palante! A Brief History of the Young Lords

Latin Liberation News Service: The Newspapers of the Young Lords Organization by Michael Gonzales

Puerto Rico en mi corazon: The Young Lords, Black Power and Puerto Rican Nationalism in the U.S., 1966-1972 by Jeffrey O.G. Ogbar

The Health Initiatives of the Young Lords Party by Theresa Horvath

History of the Development of the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization

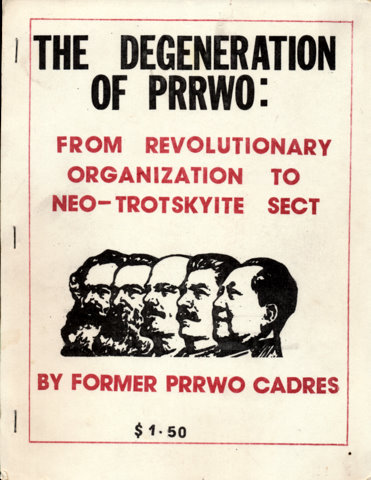

The Degeneration of PRRWO: From Revolutionary Organization to Neo-Trotskyite Sect by Former PRRWO Cadres

Lessons from the Degeneration of the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization by I Wor Kuen

Palante! Siempre Palante!, Interview with Richie Perez

Pa’lante: The Direct Action Campaigns of the Young Lords Party by Andrew Winston Falion

Primary Background Materials

The Young Lords: A Reader Edited by Darrel Enck-Wanzer

13 Point Program and Platform of the Young Lords Party

Ideology of the Young Lords Party

YLP Congress transforms party into workers group by Stephen Torgoff

UNITY: Rising Trend in the Communist Movement – Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization by the October League (M-L)

HRUM sums up hospital organizing by Stephen Torgoff

Palante, 1970-1971

Polemics

What Road for the Puerto Rican Movement? by the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization

What Road for the Puerto Rican Movement? – PSP Replies by the Puerto Rican Socialist Party

Primary Documents

Resolutions and Speeches. 1st Congress. Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization (Young Lords Party)

National Liberation of Puerto Rico and the Responsibilities of the U.S. Proletariat

In The U.S. Pregnant With Revisionism: The Struggle for Proletarian Revolution Moves Ahead. The Political Positions of the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization

[Back to top]

Communist League

One of the largest new antirevisionist groups to surface in the late 1960s, the Communist League (CL) was distinct in a number of ways. It had direct roots in the Communist Party USA and the main “second wave” group, the Provisional Organizing Committee (POC). It disdained the New Left, student movement origins of the new communist movement groups. Unlike the Revolutionary Union and the October League, which also grew out of local collectives in California, CL came directly from an organizing effort in a black community.

Beginning as an expelled chapter of the POC, these Marxists (five) held a meeting in Watts California to establish the California Communist League in 1968. Watts was the site of the furious urban uprising of 1965. The California Communist League (CCL) drew into its orbit young radicals galvanized by the Chicano Moratorium and won them over to the idea of building a revolutionary party of the proletariat. The CCL emphasized studying and developing Marxist-Leninist theory (based on standard texts from the Stalin era), mastering the legacy of the Third Communist International, and the training of an organization of revolutionaries in Marxism as its purpose and the only basis for party building.

Like the POC, CCL had a membership and leadership core including all people of color, ethnicity and national origin and emphasized the importance of the national-colonial character of the oppression of African Americans and other people of color to the proletarian revolution. It adopted the slogan “Free the Negro Nation,” based on its own theoretical variation on the earlier CPUSA thesis that African Americans in the historic plantation area of the deep south, along with the whites living there, together constituted a nation within the multinational state of America, and the right of self-determination was applicable to this nation of black and white peoples.

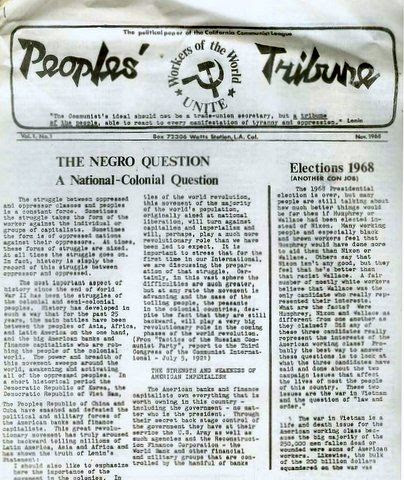

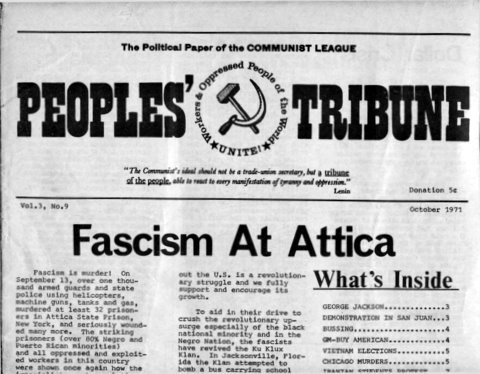

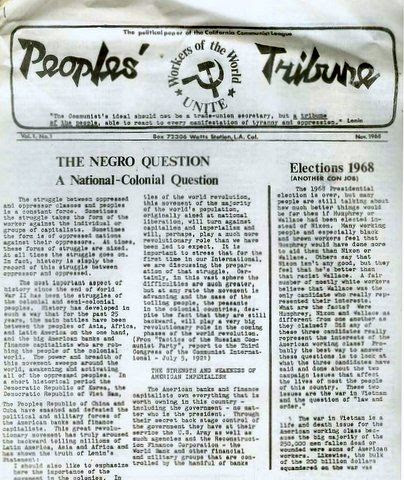

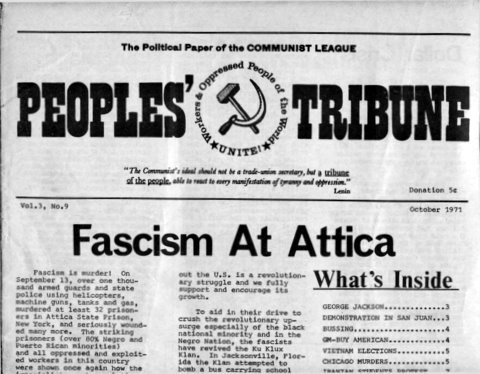

Beginning in 1968, it launched a newspaper, the People’s Tribune. The People’s Tribune was propaganda heavy, in conformity with what the Communist League viewed as its purpose and mission, the creation of an organization of revolutionaries based on Marxist theory rather than what CL called the spontaneous or mass movement, from which it drew recruits. As it expanded nationally in 1970, the group renamed itself the Communist League.

While expressing unconditional support for the Chinese revolution, and siding with the Marxist section of the CCP’s denunciation of Khrushchev revisionism, the CL, unlike the Revolutionary Union and the October League, held back from a full-blown embrace of Maoism. CL’s publishing efforts reprinted 1930’s Communist texts, including Textbook of Marxist Philosophy 1937, Problems of Leninism, Stalin’s speeches on the American Communist Party, R. Palme Dutt’s Fascism and Social Revolution, the History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolshevik), and revived interest in the writings of Stalin, including Foundations of Leninism.

Historical Works

The Dialectics of the Development of the Communist League

Review of our work by the Communist League

Critiques and Polemics

Letter from an Expelled Member of the CL (formerly the CCL) by Susan Y. [Proletariat, Vol. 1, No. 1]

The League’s ’Dogmatism’ and the ’Creative Marxism’ of Susan Y. A Reply to her Letter by J.A. [Proletariat, Vol. 1, No. 1]

The Struggle of Small and Medium-sized Nations by the October League (Marxist-Leninist)

CL Replies to Attack, (Part 1), (Part 2) by the Communist League

Reply to October League (ML): On the “Young Communist Movement”, (Part 1) , (Part 2) by the Communist League

Sham Congress Called by Communist League by the October League (Marxist-Leninist)

Reply to October League (ML): Call for Unity of Action Against Fascist Offensive by the Communist League

A United Front in the U.S.? by the October League (Marxist-Leninist)

International Report by the Communist League

Which Side Are You On?, (Part 1), (Part 2), and (Part 3) [A Critique of the CL’s International Line] by Carl Davidson

The Future is Bright: A Response to the Communist League by the October League (Marxist-Leninist)

’Leftist’ scabs in Chinatown strike by Morris Wright, Guardian Bay Area Bureau

Better Defender of the Bourgeoisie than the Bourgeoisie Itself – On the ’Communist’ League by the Workers Viewpoint Organization

Primary Documents

California Communist League

An Outline for the Study of Marxism-Leninism

The CPUSA’s Views on the State; or, Right-wing ’Communism’, a Senile Disorder by C.J. [Proletariat, Vol. 1, No. 1]

Fascism at Attica

May Day 1972: Four years of Growth and Struggle

Reformism vs. Revolutionary Struggle in the Labor Movement

Negro National Colonial Question

Report on the National Question

How the Revolutionary Union Renders Lenin More Profound While Aiding the CPUSA

Party School Report on the Dictatorship of the Proletariat

The Negro Nation–Colony of USNA Imperialism

Regional Autonomy for the Indian Peoples!

Regional Autonomy for the Southwest

Appalachia

On Proletarian Morality by Nelson Peery [from Proletariat, Vol. 4, No. 1]

Periodical

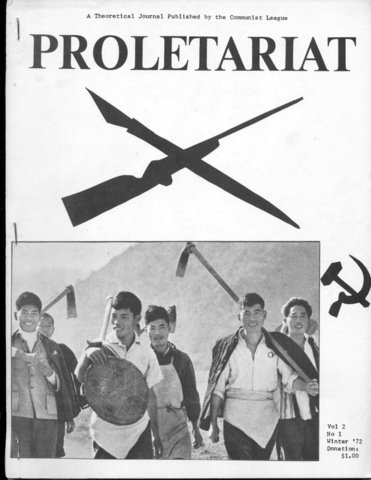

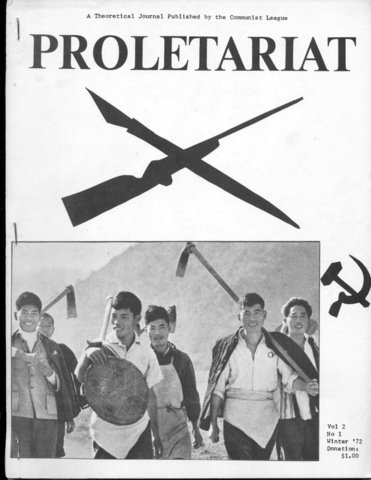

Proletariat

[Back to top]

American Communist Workers’ Movement (Marxist-Leninist)

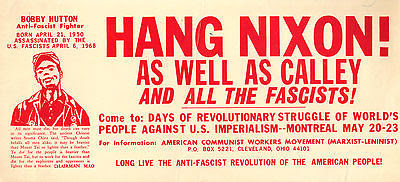

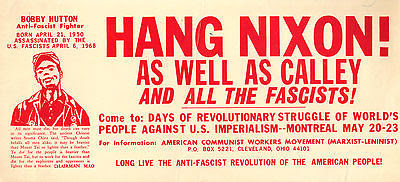

The American Communist Workers’ Movement (Marxist-Leninist) [ACWM (M-L)] dates its origin to the Cleveland Draft Resistance Union (CDRU), formed in 1967. As CDRU members began to broaden their political outlook, they formed the Workers’ Action Committee (WAC) and expanded their activities beyond anti-war work to include community organizing, strike support, and the study of Marxism. During this period, the WAC also developed close relations with the Canadian Communist Movement (Marxist-Leninist). The CCM (ML) – which later became the Communist Party of Canada (Marxist-Leninist) – was part of the “Internationalist” tendency founded by Hardial Bains and also included groups in Britain and Ireland. The WAC was attracted to the CCM (M-L)’s openly Maoist propaganda coupled with the aggressive manner in the way it waged its campaigns.

During a “North American Conference of Anti-Imperialist Youth” in Regina, Canada, in May, 1969, the WAC was re-organized as the American Communist Workers’ Movement (M-L). The ACWM (M-L), which soon expanded beyond Cleveland to other cities, was marked by a unique language and aggressive propaganda style, which often borrowed from formal Chinese documents and political slogans of the Chinese Cultural Revolution.

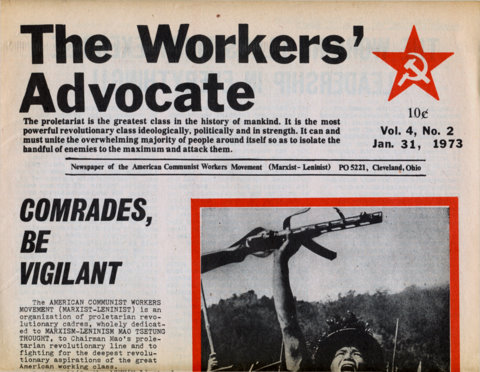

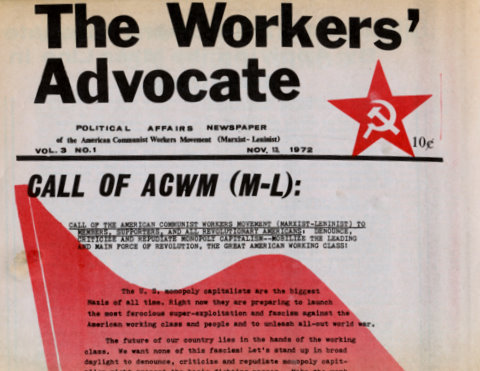

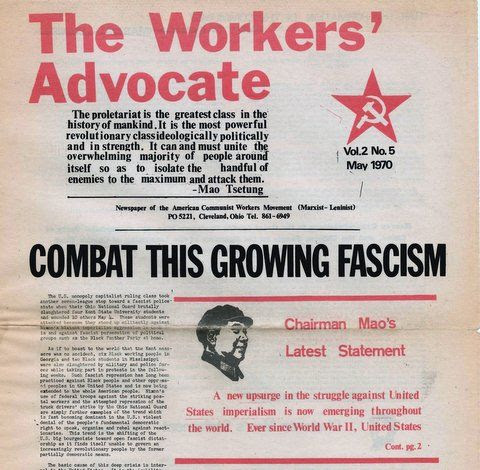

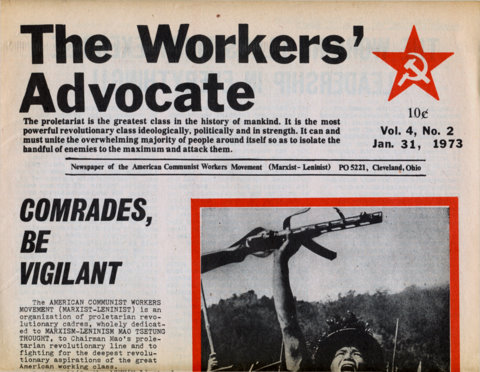

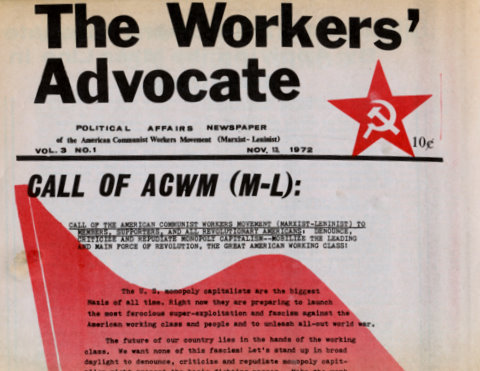

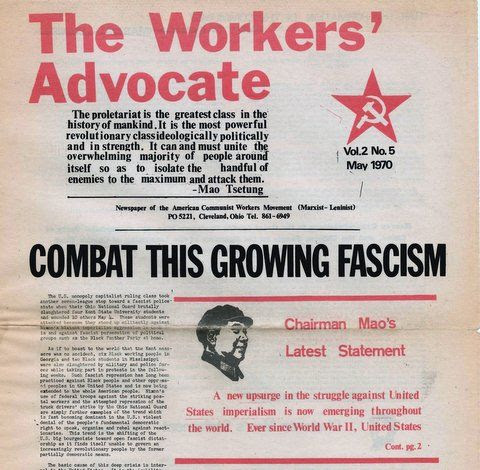

The ACWM (M-L) copied the Internationalist practice of printing a variety of newspapers. Some like the Seattle Worker and the Detroit Workers’ Voice lasted into the 1990s, while others lasted only a few issues. Also notable was its attempt to found the only daily Maoist newspaper in the United States – the People’s America Daily News – which lasted for 77 issues. The ACWM (M-L) would settle on the Workers’ Advocate, published from 1969, as its national voice.

Briefly, in 1970, the ACWM (M-L) held discussions with the Revolutionary Union, but rejected what it felt was RU’s emphasis on building local collectives rather than a national cadre party. In 1971, the ACWM (M-L) undertook one of its most ambitious projects – the formation of the Black Revolutionary Party (BRP) as an attempt to recreate the declining Black Panther Party by copying its platform and politics with a more explicitly Maoist cast. After a few months of publishing a paper and organizing community projects, the effort was abandoned as a failure.

In 1972, the ACWM (M-L) joined with the Communist League and other smaller groups to call for a Conference of North American Marxist-Leninists to unite the different groups into a new Marxist-Leninist party. (Materials on the Conference and the CL’s and the ACWM (M-L)’s subsequent party-building efforts are covered in The New Communist Movement: Intial Party-Building Campaigns, 1973-1974 .)

Historical Works

Reminiscences of the Birth of our Trend by Tim Hall

Regina Conference, An Historic Turning Point in Party-building in North America

On

the 20th anniversary of the Internationalists: The

Myth of the Glorious Past–CPC(M-L)’s Pretext for International

Factionalism by the Marxist-Leninist Party

A Short Talk on the History of the ACWM(M-L) and its Method of Work and Organization

The ACWM(M-L)’s Attitude Towards the Panthers and the Black Revolutionary Party

The ACWM (M-L) and the resistance movement

Background Materials

Letter from an Organizer in the Army by the Cleveland Draft Resistance Union [leaflet]

Don’t Be a Sucker (A message to White People) by the Cleveland Draft Resistance Union [leaflet]

Can McCarthy Bring Peace? by the Cleveland Draft Resistance Union [leaflet]

Johnson Quits (April Fool) by the Cleveland Draft Resistance Union [leaflet]

Primary Documents

North American Conference of Anti-Imperialist Youth [Regina Conference] [flyer]

Statement of the Formation of the American Communist Movement (Marxist-Leninist)

Working People Need Mao Tsetung Thought – A Spiritual Atom Bomb of Infinite Power

The Rise of Fascism

Report on North American Anti-Imperialist Conference

Meeting Announcing the Formation of Rhode Island Student Movement, Anti-Imperialist [flyer]

ASM Rising Nationwide!

Historic Conference Fights for People’s Right to Organize Politically

Combat this Growing Fascism

Worker and Student Mao Testung Thought Propaganda Teams Go Forth Boldly

Revolutionary Masses Expose “Hard-hats” as Paper Tigers and Militantly Resist Attacks of Fascist Police! (leaflet)

AN OPEN LETTER (leaflet)

DENOUNCE THE FASCIST COURTS!! (leaflet)

YOUNG COMMUNISTS FIRMLY OPPOSE THE FASCIST E. CLEVELAND COURTS AND DEFEND THE PEOPLE’S RIGHT TO ORGANIZE POLITICALLY!! (leaflet)

ALL REACTIONARIES ARE PAPER TIGERS (leaflet)

Coming October 1st: People’s America Daily News!

A People’s Press is Born!

Hail the Formation of the Black Revolutionary Party

Politically organize armed defense units by the Black Revolutionary Party, USA

Class Struggle within the Movement is Just Fine! by the Rhode Island Student Movement

Youth and Students Unite!

Organize Actual Struggle Units

Class Struggle at the Place of Work!

Hail the Victory of the Proletarian Revolutionary Line of the Buffalo Student Movement Conference!

How we are building an Actual Struggle Unit of the American Communist Workers Movement (Marxist-Leninist) Part One

Report of the “Down with Bourgeois Individualism” Study Group

Revolution! Not Reforms! by the Ann Arbor Student Movement

Periodicals

Workers’ Advocate

North America News

Rhode Island Student

Mass Line in Culture

Ann Arbor Student

[Back to top]

Sojourner Truth Organization

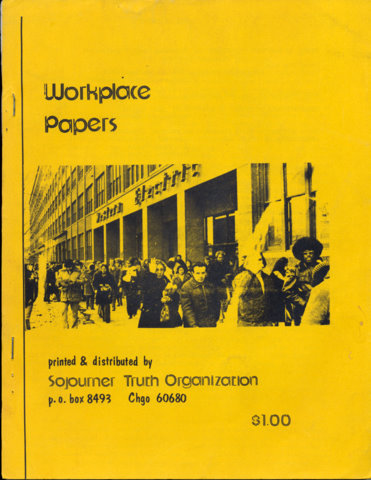

One of the more innovative groups of the New Communist Movement was the Sojourner Truth Organization (STO), which distinguished itself by not taking its politics from previous models and by creatively crafting a unique set of views and organizational approaches. STO was founded by activists in the RYM II faction that emerged at the time of the last SDS convention in June 1969, and its unique character owed much to these origins.

Several positions distinguished RYM II. Unlike the Communist Party, it saw revolution as an immediate question, and opposed Soviet revisionism. Unlike Progressive Labor and the Trotskyists, it encouraged support for national liberation movements and governments that identified with armed struggle against imperialism: Albania, China, Cuba, North Korea and Vietnam. RYM II identified strongly with the Black Panther Party and other revolutionary black nationalists. It saw a material basis for racism in the working class in “white skin privilege.” Finally, unlike its former co-factionalists in Weatherman, RYM II saw organizing American workers as the main basis for revolution in the U.S.

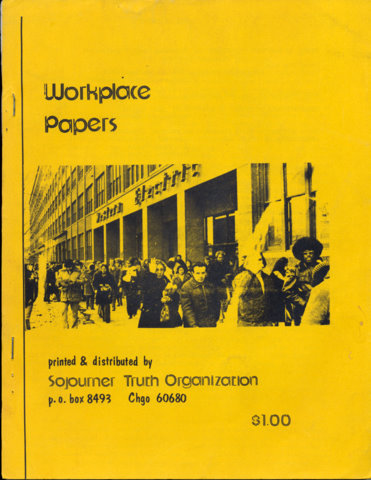

STO took the last two points as its primary focus. It identified less with anti-imperialist governments and Marxist-Leninist parties, and more with the organizations in Europe which were challenging the dominance of bureaucracy-ridden, hidebound unions in workers’ struggles. In 1969-70, it looked more to the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, which helped build revolutionary union movements in Detroit auto plants, than to the street-oriented Black Panther Party. STO argued against simplistic appeals to class unity (“Black and white, unite and fight”) which were grounded on an idealized notion of American working class history and ideology.

STO was involved in several industrial actions in Chicago, their chief locale, and produced polemics that challenged New Communist Movement principles, including the vanguard party, traditional forms communist work in labor unions, and iconic views of communist history. It also brought its anti-racist critique to social movements: the Vietnam peace movement, the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union and others. STO’s sympathies moved from Mao to the post-Trotskyist political-cultural criticism of C.L.R. James, and its identification with the NCM was short-lived.

Because much of STO’s literature is already on-line at the Sojouner Truth Organization (1969-1985) Digital Archive, we are not reproducing an extensive collection of it here on EROL.

Historical Works

Outline History of Sojourner Truth Organization

Notes for Development of a Revolutionary Strategy by Don Hamerquist

Critiques and Polemics

White Blindspot by Noel Ignatin and Ted Allen

A Critique of “White Blindspot”: A Contribution to the Struggle against a Petty-Bourgeois Line on the Question of Working Class Unity by Alan Sawyer

On the So-called Bankruptcy of Contract Unionism [Reply to Hammerquist and Ignatin] by Clay Newlin of the Philadelphia Workers Organizing Committee

Primary Documents

Towards a Revolutionary Party

The United Front Against Imperialism?

Mass Organization at the Workplace

White Supremacy and the Afro-American National Question

[Back to top]