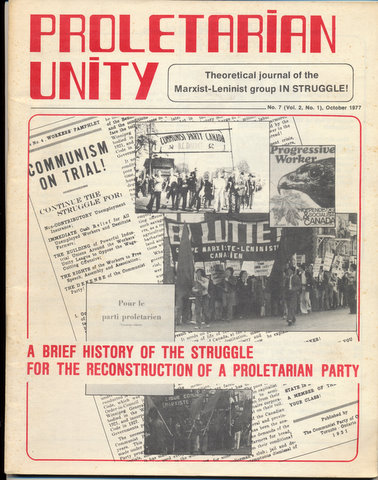

First Published: Proletarian Unity, Theoretical Journal of the Marxist-Leninist Group In Struggle!, No. 7 (Vol. 2, No. 1) October 1977

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The swindlers of Capital have launched their most savage attack against the Canadian proletariat since the end of the Second World War. The difficulties which the Canadian bourgeoisie is presently facing bring it to try and shift the weight of the crisis onto the backs of the working class and the masses. The capitalist class has joined ranks behind its instrument of repression, the bourgeois State, to bring down laws, one more repressive than the next, on the heads of the people. At the heart of this attack we find the sinister law C-73, the Wage Control Act, an instrument with which the bourgeoisie seeks to put down the revolt of the working class, as well as to intensify its exploitation in order to increase its profits. This law is an instrument to Impoverish and divide the proletariat.

It’s in these conditions that the resistance of the Canadian proletariat is growing. Particularly fervent in Quebec in the early 70’s, this outburst of combativity is now generalized throughout the entire country. Everywhere, the living conditions of the working class and the masses are the same – debts, unemployment, repression. But, despite the importance of this outburst of combativity, reality is there to remind us of its fragility, and of its incapacity to overthrow the cause of our troubles – capitalism. Of course there are victories, but the struggles must always start all over again. Often, it’s necessary to go out on strike for six months just to be able to keep what we already had. Often the struggles are directed onto all sorts of dead end paths which, at the end of the line, cause us to put into question having fought at all.

What the facts cruelly teach us each day is that the working class is missing a revolutionary leadership which could put it onto the path of attack against the bourgeoisie. A leadership which would lead it in the struggle to the end against capitalism and its hardships.

Because they struggle for the superior interests of the masses, because they represent the proletariat’s future, Canadian Marxist-Leninists have put the reconstruction of a revolutionary leadership of the proletariat at the very center of their preoccupations and actions. Today, to make revolution, is to struggle for the reconstruction of the Revolutionary Party of the proletariat, the Marxist-Leninist Party, And it is only by becoming involved in this struggle that we can claim to defend the real interests of the proletariat.

At the present time, a part of the movement, while it claims to struggle for the Party, has in fact, a tendency to dangerously subordinate this task. If this tendency develops and is not rectified, it will lead to revisionism, to the betrayal of the revolution. To wage struggle against this inclination to subordinate the struggle for the Party, and thus contribute to the revolutionary progress of the entire Canadian proletariat, we present our readers with this brief history of the struggle for the reconstruction of the Proletarian Party in Canada.

In regard to our task, the building of the Marxist-Leninist Party, we are going to retrace the history of the Canadian communist movement from the degeneration of the Communist Party of Canada up until our time. We try to establish which of the contradictions constituted the motor of the class struggle at each phase in the development of the movement. We also will try to identify who had the proletarian line, and who really made the struggle for the reconstruction of the Party advance.

Although our movement is still young, it is necessary to write its history. And it’s important to make it known to the masses. Our movement is no longer what it was five years ago. At that time the number of militants calling themselves Marxist-Leninists could have been counted on one hand. Today, the best elements of the intellectual youth are rallying to our ranks in waves. As well, more and more men and women workers are taking hold of the invincible arm of Marxism-Leninism and defending it before their class brothers and sisters.

In but a short time the movement has grown with the addition of new militants, full of revolutionary ardour, but often with little knowledge of the struggles which have led to the birth of this movement. However, the knowledge of these facts is essential to measure the depth of the line struggle which currently runs through our movement, and to grasp what is really at stake.

To act on social phenomena, one must first learn about the entire process of their development. Because social phenomena do not come into being all at once. They have a life, a history and a development. Thus the errors that we see in the movement today did not develop overnight. They existed before. And it is precisely by knowing what they were like and how they were modified to become what they are today, that we can really understand and correct them. In other words, we believe that it is by grasping what was, and by criticizing it, that we can forge tomorrow’s victories. This text is also meant to be an instrument of study and debate in preparation for the Fourth National Conference of Canadian Marxist-Leninists which will deal with the tasks of Canadian Marxist-Leninists. Our group has been holding these National Conferences of Canadian Marxist-Leninists for a year now. These conferences are a part of the struggle to unite all Canadian Marxist-Leninists into a single organization, on the basis of a programme whose very elaboration presupposes a systematic demarcation between correct and false ideas, between the bourgeois and proletarian lines. The conferences have the precise goal of accentuating the polemics and the direct confrontation of the points of view within our movement on the main questions of programme in a spirit of unity and within a systematic organizational framework. Up until now, there have been three conferences. The first dealt with the unity of Canadian Marxist-Leninists, the second with the path of the revolution in Canada, and the third with the international situation. The fourth will touch on the current tasks of Canadian Marxist-Leninists, that is, the struggle which Canadian communists must wage to give the Canadian proletariat a single revolutionary leadership. The experiences of the glorious Bolshevik, Albanian, and Chinese revolutions, prove that without its Marxist-Leninist Party, the proletariat cannot be victorious. We feel that it is of utmost importance, that we intensify the polemics and the debates within the movement and the masses on the current tasks of Canadian Marxist-Leninists. This is a pre-condition to moving towards our central objective - the reconstruction of the Party of the proletariat. The study of the history of the line struggle within our movement on the question of the Party is a key element to grasp in order that the debate becomes more concrete and rigorous. Our movement has already acquired rich experience. It’s time to generalize it.

For some, the Communist Party of Canada became revisionist in 1956 when the Party officially lined up on the side of the Soviet revisionists against the Marxist-Leninist line which was vigorously defended by the Communist Party of China and the Party of Labour of Albania. This point of view is erroneous. It takes into account only the most superficial aspects. If we really want to clear things up for the Canadian proletariat and arm it in the struggle to the finish against revisionism, we will not be satisfied with something which was finally nothing more than the end product of a process which had begun well before – the process of the degeneration of a proletarian party into a bourgeois reformist party. This task has hardly begun in our movement and there is absolute necessity to pursue and deepen it. The success of our current struggle against opportunism within the Marxist-Leninist movement, the success of our struggle to rebuild the authentic vanguard Party of the Canadian proletariat depend on it.

Thus it is not by accident or by intellectual curiosity that we have begun this history of the Canadian Marxist-Leninist movement with the presentation of our viewpoint on the development of revisionism within the Communist Party of Canada. We have done this because we are convinced that the lack of polemics on this point on the part of Canadian Marxist-Leninist groups constitutes a major obstacle in our current struggle against revisionism and opportunism. Finally we should add that we are undertaking this debate while being fully conscious of the important weaknesses which we still have in our concrete analysis of the subject.

To go right to the heart of the subject, it was at the August 1943 Congress that revisionism became the dominant aspect of the line of the Canadian Communist Party. Not only did this Congress adopt a new name for the Party, which became the Progressive Labour Party, (PLP)[MIA Note: In English texts, the Party's name is usually abbreviated LPP] but it also adopted a new political line which was contrary to Marxist-Leninist principles. And from that moment the Party abandoned all truly revolutionary strategy and accepted to submit all of its action to the narrow framework of legalism and bourgeois parliamentarism. Instead of systematically preparing the masses for revolution, for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie, the new party proposed the election of a workers’ and farmers’ government, which later would transform itself into a socialist government – without armed struggle, without revolution. The Party thus tried to make the masses believe that the bourgeoisie, by itself, would abandon its class privileges, without repression, without having recourse to the violence of its State apparatus.

This was a clear betrayal of the entire history of the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat, betrayal of the Marxist-Leninist principles on the question of the State and revolution.

Further still, the PLP even went so far as to propose to the proletariat that it ally itself with the Liberal Party, with a party which long had served the interests of the grand Canadian monopoly bourgeoisie, a party which had long waged open war against the communist and workers’ movement – forbidding strikes, freezing wages, rationing food-stuffs – all of that to fatten great Capital. It’s with this party that the PLP proposed an alliance against the Conservative Party! In brief, the only solution that the PLP offered to the masses who were cruelly oppressed by Capital, was to support one faction of Capital against the other. In fact, what they preached to the masses was to accept their miserable life conditions, and nothing more!

This act of betrayal, this denunciation of the revolution, were also accompanied by a complete abandonment of Marxist-Leninist principles on the very nature of the Party. In effect, the PLP no longer defined itself as a class Party, as the Party of the proletariat, but rather as a “Party of all the workers”. This sad refrain which is still defended today by the revisionists and Trotskyists, has but one goal – to make the Party acceptable to the hesitant and unstable elements of the petty-bourgeoisie. The history of the Paris Commune and of the Bolshevik revolution on which all authentic communist parties base themselves, show that, on the contrary, the revolutionary Party can include these elements to the extent that they abandon the point of view of their class of origin and entirely and unreservedly adopt that of the only class which is revolutionary to the core, the class point of view of the proletariat. Only the Party of the proletariat, composed of its most conscious and devoted elements, can wage the revolutionary struggle of the masses to its final victory against the bourgeoisie.

Consistent with its line, the PLP dissolved its factory cells, which are the fortresses of all authentic communist parties, built from within the proletariat, to constitute itself on an electoral basis like all other bourgeois parties.

For all of these reasons it is correct to affirm, that as of 1943 the CP (which had become the PLP) had abandoned the path of the revolution, the political independence of the proletariat, and had ceased to be an authentic proletarian party. From that moment up until it rallied to the positions of the Soviet revisionists, the gangrene of revisionism led the party from split to split, devoiding it of its authentic revolutionary militants, in order to let In a series of opportunists and petty-bourgeois and bourgeois careerists.

In 1945, Fergus McKean, who was then secretary of the provincial wing of the Party in British Columbia, in a book entitled Communism versus Opportunism[1], launched a full scale attack against the revisionist line of the PLP, and put forward the necessity of recreating a new Party. McKean did not succeed in organizing real opposition to the leadership of the PLP and was quickly expelled from the Party. He created a short-lived party which only lasted a few months.

The PLP, and before it the CP, had always had an erroneous line on the Quebec national question, and had never been a firm defender of the Quebec nation’s right to self-determination, nor a solid fighter against great nation chauvinism in English-Canada. At the 5th Congress of the PLP in 1949, there was a split within the party because of its chauvinist line concerning the national question. 300 of the 700 delegates left the Party when the leaders refused to change their positions. This split led to the departure of the major part of the Party’s forces in Quebec. They, for their part, fell into narrow nationalism.

The great nation chauvinism of the English-Canadian militants increased the narrow nationalism of the Quebec militants. From the viewpoint of the interests of the entire Canadian proletariat, the two parties were in the wrong, both their positions leading to a reinforcement of the division of the proletariat on a national basis.

Thus the fall of the revolutionary general headquarters of the Canadian proletariat led to the crumbling of the Canadian proletariat’s unity. This sad episode in the line struggle within the PLP should remain engraved in the memory of the Canadian proletariat as well as in that of present-day Marxist-Leninists. The lesson which must be drawn is that the building of an authentic revolutionary workers’ Party is an essential condition for the iron unity of the Canadian proletariat, and that this Party must be built in the struggle against the two faces of bourgeois nationalism – great nation chauvinism and narrow nationalism.

When in 1957, the PLP formally rallied to the line of modern revisionism put forward by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, it was a party which had already developed a revisionist line ten years before. Other struggles broke out in the Party which resulted in other splits. The most important of these was the struggle waged by the militants who later founded the Progressive Worker Movement (PWM).

In the late 50’s and early 60’s, an extremely important line struggle opposing Marxism-Leninism to modern revisionism was intensified within the international communist movement. This line struggle was waged parallely on the international level and within each party. On the international level the Party of Labour of Albania and the Chinese Communist Party waged principled struggle against the clique of renegades which has usurped the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and their allies in the different Communist Parties. Unmasked, the pseudo-communist Khrushchev and his gang of unscrupulous bourgeois power-seekers, provoked the split of the international communist movement by plotting to expel the Communist Party of China and the Party of Labour of Albania.

This split between Marxism-Leninism and modern revisionism on an international scale, sharpened the contradictions between the two lines within all the Communist Parties in the world. In all of these Parties the revolutionary elements, basing themselves on the correct positions elaborated by the Albanian and Chinese comrades, undertook the struggle against revisionism with new ardour. Such a struggle took place within the Communist Party of Canada. It broke out with the publication of the programme Socialism for the Sixties, which the party’s leadership presented to its members in 1962. This programme, which appeared at a period of economic progress in

Canada, was one step more in the consolidation of the revisionism which was already present within the CP. It questioned the historical role of the proletariat, identifying it not as the only class that is revolutionary to the core, but rather as one of the forces of the nation. Its objectives were merely to reduce the power of the monopolies. It proposed reforms and changes in the “structures of the economy”, in the structures of capitalism. It called on the working class to reform capitalism rather than to destroy it.

Early in 1964 in Vancouver, Jack Scott and his cell companions who opposed the line of the CP, created the Canada-China Friendship Association, which, by the way, was the first to be created in a Western capitalist country. This action was consciously and clearly the sign of a proletarian position which opposed the bourgeois line of the CP and all the revisionist parties, with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at their head. This too obvious support for China on the part of Scott and his companions led to their expulsion from the Party in the summer of 1964. They then tried to bring together all Canadian revolutionary forces, but their attempt failed.[2] Turning inwards to British Columbia, they founded the Progressive Worker Movement (PWM), in October 1964.

Although it was in fact the most vigorous attack at the time against revisionism in Canada, the very creation of the PWM is the consequence of the first failure in the struggle to rebuild an authentic proletarian Party. The history of this group was to be marked by the repetition of this defeat, always for the same reason. Even if it was the first Canadian group to wage struggle against revisionism during the 60’s, the PWM was never really able to break with revisionism. And we are going to look at the reasons why.

In a Declaration of Principles, the Central Committee of the PWM wrote in the first issue of the newspaper Progressive Worker:

“The contemporary period is marked by a resurgence of revisionism in the service of imperialism and demands a united and unyielding struggle on the part of Marxist-Leninists in defence of the basic concepts of Marxism-Leninism and for the socialist revolution.”[3]

After having explained the role of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as that of main leader of modern revisionism, the leadership of the PWM analyzed the Canadian Communist Party in the following terms:

“The communist party has fallen into the hands of the revisionists led by Morris and Kashtan[4] who are supported and encouraged by the Krushchevites. They engage in vicious unprincipled attacks against the Communist Party of China (foremost defender of Marxism-Leninism in the international movement): they promote the ’parliamentary’ and ’peaceful’ road to Socialism, thus disarming the working class in the face of capitalist class violence; they abandon the Marxist-Leninists concepts on Socialist Revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat: they abandon proletarian internationalism in favor of allying themselves with the Canadian liberal bourgeoisie; they accept – and try to get the working masses to accept – the ideology of social democracy, the main bulwark of capitalism in the labour movement. Having abandoned Marxism-Leninism, the CP leadership is quite incapable of leading the struggle for the realization of a program of fundamental working class demands”.[5] At the end of its declaration of principles the Central Committee of the PWM launched an appeal for the unity of the other Marxist-Leninists in the country to create the Party.

“We propose that the Marxist-Leninist workers’ groups begin discussing plans for holding a national conference in the near future for the purpose of organizing a Marxist-Leninist Workers’ Party in Canada which shall dedicate itself to raising again, to a place of conspicuous honor, the proud banner of proletarian struggle”.[6]

The PWM thus clearly placed its task at the level of the struggle against revisionism, and from that point of view, we must accord it much merit. Particularly on the ideological level, it traced a first demarcation between Marxism-Leninism and modern revisionism and all other opportunist and counter-revolutionary ideologies, such as Trotskyism, Castrism, and social democracy. It unceasingly denounced the class collaboration practiced by the traitors of the CP. On the international level, it denounced the manoeuvres of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (such as the invasion of Czechoslovakia), and firmly supported the socialist countries and the struggles of the peoples against imperialism, particularly the just struggle of the Indochinese people. It once again took up the historical tradition of the international communist movement by establishing a center for the distribution of Marxist-Leninist books, by placing revolutionary songs in the place of honour, and by recalling the high points of the proletariat’s struggle, (Commune of Paris, October Revolution, Winnipeg General Strike). The PWM was a firm defender of the immediate interests of the masses, participating in the struggles for the right to work, opposing work speed-ups, fighting for the improvement of the masses’ living conditions and struggling for the democratization of unions.

However, it committed two determinant errors which prevented it from really rebuilding the Canadian Marxist-Leninist movement. It abandoned the tasks of rebuilding the Proletarian Party, as well as that of applying the independent policy of the proletariat on all questions, that is, a policy distinct from all the other classes of Canadian society. From then on, it had irremediably started down the slope of revisionism.

The PWM was characterized by its spontaneism with regard to party building. From its creation, the PWM had established the necessity of uniting the revolutionary forces in the country and creating the Party. But to be truthful, this question was more a declaration of intention. Except for the last year of Progressive Worker[7], where it constituted the subject of a few articles, the question of the Party was never really the object of intense propaganda in the PWM’s press. Already, by its creation the PWM failed in its attempt to create the Party on a national scale. This failure rapidly led it to turn inwards on itself, to capitulate before the struggle to be waged for the whole Canadian proletariat.

Afterwards, it was to raise localism to the level of a principle for the construction of the Party, by putting forward the unification of communists on a regional basis before their unification on a national basis. In fact, the militants of the PWM devoted the essential of their energies to the development of their work In the union movement, without submitting this task to the task which must be the first of all the tasks of communists within the workers’ movement, that is, the rallying of advanced elements of the proletariat to communism through the activity of communist agitation, propaganda and organization.The Canadianization of the Unions

Throughout the greater part of its history, all of the PWM’s tactics were to be determined by the call for the Canadianization of the unions. According to these comrades, it was necessary to rid the Canadian unions of the hold which the American union bureaucrats had on them and return them to the militant control of the rank and file in order to turn them into arms which were not only defensive, but also offensive, for the liberation of the country and the emancipation of the workers.

“Revolutionaries must, therefore, strive to show the working class how to use the unions as a weapon to shape their future, a revolutionary weapon for the abolition of the system of exploitation of man by man”.[8]

And further on:

“It will, therefore, be necessary for us to raise this question [the creation of an independent trade union movement – Proletarian Unity editor’s note] in conjunction with the whole broad front of struggle and do more effective work in pointing out that the defeat of the US bureaucracy is essential to democratic worker control of the unions and that such control is a necessary prerequisite for turning the unions into the effective fighting organs they can and must become in order to defend the rights and living standards of the workers and free our land from alien domination”.[9]

In fact, the PWM even conceived of the creation of such an independent Canadian union movement as:

“the primary task confronting Canadian workers at this point in history...”[10]

This was in fact a disavowment of the teachings of Marxism-Leninism on the building of the proletarian Party, and the most base economism. Furthermore, the question of the Party rapidly became nothing but a mere reference in the PWM’s line. In fact, its work consisted essentially of “reviving” unions, seeking to make them militant by radicalizing workers’ struggles. On this point as on many others, the great similarity between the PWM’s practice and the current economist line of the Canadian Communist League (M-L) should be noted. The latter does the same work only this time with the slogan of “class struggle unions”, which is no different than the “militant unions” of the PWM.

Moreover, the PWM and the League do not have the monopoly on this sort of practice which limits communist activity in unions to the radicalization of local struggles. It also characterized the line of the Regroupement des Comites des Travailleurs (RCT – Federation of Workers’ Committees), an opportunist group whose still active militants have today joined the ranks of the League. This practice is like an old refrain which continues to reappear throughout the history of the movement, and which certain are still singing.

The PWM’s abandonment of the central question of the Party was also manifested by the little importance that it accorded to the elaboration of revolutionary theory. On this point Marxist-Leninists have always been clear. As Lenin himself stated: “Without revolutionary theory there can be no revolutionary movement”. To this extent, the first task that the PWM should have taken up was to produce and distribute a rigorous criticism of the revisionism of the Communist Party of Canada, among the masses. By rigorous criticism we mean a criticism which would have analyzed the concrete history of the development of revisionism in our country, unmasking all of the most important manifestations by opposing them with the proletarian line.

On the contrary, the criticism produced by that group was partial and unilateral. Partial because it touched only certain aspects of the revisionist line, in particular union work and the attitude with regard to US imperialism. Unilateral because often the only reply it gave was to present the opposite position. And this reply was also often accompanied by a mechanical application of the line of the Communist Party of China rather than by a creative application of that line to the concrete practice of the revolution in our country.

With regard to the Quebec national question, the Communist Party of Canada had always adopted a chauvinist position which refused to recognize the Quebec nation’s right to self-determination and to set itself up as an independent State. Once again the PWM gave a unilateral reply without making a concrete class analysis. The PWM answered the chauvinism of the CP with narrow nationalism, giving its support to Quebec independence and even going so far as to break off relations with the militants in Quebec on its own initiative. The importance of this error should not be underestimated for its direct effect was to maintain the brick wall which already separated both the proletariat and the revolutionary movements of the two nations.

The modern revisionists in Canada as elsewhere, had, at the time, abandoned the revolutionary struggles against American imperialism preaching their rot about peaceful coexistence. According to the correct analysis of the Chinese Communist Party and the Party of Labour of Albania, American imperialism was at the time the main enemy of the peoples on a world scale. Mechanically applying this line to the Canadian reality, the PWM identified American imperialism as the main enemy of the Canadian people, to the point of advocating the alliance of the proletariat with the Canadian bourgeoisie. Through its unilateral criticism of the Communist Party of Canada, the PWM finally ended up in practice, with this type of a line of class collaboration with the bourgeoisie.

Here we should draw our readers’ attention to the fact that this error of mechanically applying the line of another Party instead of setting down to the task of developing one’s own line in all independence, by applying the universal truth of Marxism-Leninism to the concrete practice of the revolution in one’s own country, still persist right up to the present time. Groups like Bolshevik Union (BU) and “C”PC(M-L)have developed such political laziness to the point of trying to make us believe that now the line of the Party of Labour of Albania and before that the line of the Communist Party of China could take the place of the line of the Canadian communist movement. For their part the CCL(M-L) and the Red Star Collective try to justify their propensity for supporting the Canadian bourgeoisie, by taking up as their own, the line of the Communist Party of China on the international situation. Dogmatic errors of this type if they are not rectified will sooner or later lead to a betrayal of the revolution.

Without a resolute struggle against great nation chauvinism and bourgeois nationalism, it’s impossible to unite the proletariat of the two nations, and this struggle for the unity of the entire Canadian proletariat is an essential aspect of the struggle to build a single party of the Canadian proletariat.

The abandonment of the central task of party building, and the abandonment of the work of elaborating and publishing the revolutionary theory of the Canadian proletariat, of the communist programme, could only lead the PWM to line itself up in the camp of bourgeois nationalism.

The massive penetration of American imperialist capital, organizations and culture in the ’50’s and ’60’s, and the powerful development of the national liberation movements of the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America created fertile ground for the development of petty-bourgeois anti-imperialism in our country, particularly among Canadian youth. Because of its own errors, the PWM, far from channeling this movement towards the revolutionary proletariat, found itself literally caught up in it.

In what was to be its most complete document of political line, “Independence and Socialism in Canada”, published in 1968, the PWM advocated nothing less than a national liberation struggle against American imperialism:

“Recognizing US domination as being the chief obstacle on the road to socialism, socialists should direct their efforts towards removing this obstacle. This means working among the various sectors of the Canadian population and uniting as many Canadians as possible against their number one enemy, US imperialism. A broad coalition must be built, a broad coalition whose purpose is the breaking away of Canada from the American empire, the achievement of the power of self-determination of the Canadian people”.[11]

Following this, In the same manifesto, came a whole series of tactics, which on the basis of this strategic objective, sought to rally workers, farmers, students, and petty-bourgeois intellectuals. As history was to reveal, this was to objectively divert them rather than bring them closer to the proletarian revolution. Furthermore, it is significant that in this document which was the fundamental document of the PWM, the proletarian revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat are not at all mentioned!

Thus this first attempt to organize the struggle against modern revisionism in Canada was bound to fail. And, not long afterwards, the PWM was forced to end its activities. However, its line was to be taken up and pushed to its logical conclusions by the “C”PC(M-L), that group of counterrevolutionaries which has never done anything more than try to “marxisize” bourgeois nationalism and which today still constitutes a major obstacle to the development of the Canadian Marxist-Leninist movement.

Another particularly negative effect of the PWM’s experience was that it reinforced the tendency of the petty-bourgeois intellectuals who were under its influence, particularly in the West, to retreat into small, closed study circles and to conceive of militant unionism as a model for the revolutionary work to be done within the working class. These circles, many of which still exist today, devoted themselves to studying theory completely cut off from the class struggle, and to practice which tailed after the workers’ movement. The effect of this was basically to abandon the struggle for the Party.

The history of the PWM and its failure in the struggle against revisionism is rich in lessons for the current young Marxist-Leninist movement. In the first place, it concretely shows how the struggle to elaborate the proletarian line and the communist programme is indissolubly linked to a profound and rigorous criticism of revisionism in Canada in all of the most important manifestations of its development, it also shows how in the absence of a real proletarian Party, the building of this party must be at the center of all the tasks of Marxist-Leninists. If not, we will find ourselves progressively drawn to the different petty-bourgeois and even bourgeois opportunist currents. More precisely, it indicates all of the importance of the elaboration of revolutionary theory and the revolutionary programme and their wide distribution among the masses, at this stage in the revolutionary struggle.

To fail at this duty, to be satisfied with winning immediate victories in any given struggle or on any given question, is to just as inevitably slide into opportunism and to fall into revisionism again. Finally, it permits us to understand the dialectical unity which links communist strategy and tactics. An economist tactic for work in workers’ and peoples’ struggles, or in mass organizations is a definite reflection of an attitude of collaboration and capitulation before the bourgeoisie and leads to renouncing the class interests of the proletariat. As we will see further on, these lessons apply just as much to the opportunist positions which still exist in our movement.

The result of the degeneration of the CP and the control of the workers’ movement by its corrupt stratum, the labour aristocracy, was the considerable weakening of the proletariat’s struggles in the ’50’s and ’60’s. More precisely, in the absence of a real revolutionary leadership, the proletariat found itself unarmed in the face of the open attacks of the bourgeoisie, in particular the vast “witch hunts” directed against the communists like, for example, the disguised attacks of reformism, apoliticalism and class collaboration unionism. During the ’50’s and ’60’s, all of that was to lead to a profound division within the workers’ movement, particularly on a nationalist basis, as well as to its being pushed out of the political scene.

In those conditions, the most important political movement in Canada, during the ’60’s, and even more so in Quebec, was the nationalist movement. It was even easier for this movement to develop, given the objective conditions of the period which really lent themselves to it. For it was during these years that the penetration of American imperialism was greatest. Favoured by the development of a tighter alliance with the Canadian bourgeoisie following the Second World War, American imperialism penetrated practically all spheres of our social life. On the economic level of course[12], but also in the political, military and cultural spheres.

On the Quebec scene, nationalism was even more exacerbated because of the considerable centralization of political power in the hands of the federal government during and after the war. The objective effect of this centralization was to accentuate the age-old oppression of the Quebec nation.

Thus, in Canada and Quebec, large sectors of the population reacted strongly to these phenomena. Particularly among the petty-bourgeois radicals, many began to compare their situation to that of the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America who at the same time were the impetus for a vast revolutionary movement of liberation against imperialism. Frantz Fanon’s[13] ideas on anti-colonialism, Che Guevara’s[14] on the Cuban revolution and the Black Panther movement’s[15] in the United States, began to ferment in the minds of many revolutionary intellectuals. Groups like Partis-Pris[16], the Front de Liberation du Quebec (F.L.Q.) and Red Morning[17], took up their wide propagation. Today’s Marxist-Leninists and conscious workers must understand the role that the nationalist movement played at that time in the development of the revolutionary movement in Canada. This wide-scale political movement set great social forces into motion and no class was left indifferent. It was a powerful factor in making the masses conscious of the necessity of political action, even if it objectively maintained the proletariat under the domination of the bourgeoisie. In fact, to a great extent the current Marxist-Leninist movement was founded by the revolutionary elements of the petty-bourgeoisie who came out of the nationalist movement. How is that possible?

The deepening of the general crisis of imperialism and its effects in Canada in the ’60’s caused a fraction of the petty-bourgeoisie (intellectuals, students, social-animators) to become radicalized. For all of this fraction, the nationalist movement constituted the grounds for this radicalization. But rapidly, the stupendous growth of the workers’ movement in the late ’60’s, revealed what was really at stake in the class struggle in Canada. Among the radical intellectuals, revolutionary elements stood up and proceeded to criticize the reactionary character of nationalism and to adhere to Marxism-Leninism by seeking to approach the workers’ movement.

Because of the material conditions of the exploitation of the proletariat in capitalist society, the workers’ movement on its own cannot become a conscious movement, a Marxist-Leninist movement. A scientific understanding of the economic relations in society cannot spring up from its daily struggle. For the workers’ movement to become a revolutionary movement, it is necessary to import this knowledge of the economic relations of society, Marxism-Leninism, from outside.Historically, bourgeois intellectuals, having broken with their class, have been the ones to elaborate revolutionary science, and it is their task to carry scientific socialism into the workers’ movement.

But while fulfilling their historic role of carrying Marxism-Leninism to the proletariat so that it can assimilate it, these intellectuals have also brought with them the shortcomings of their class. These shortcomings often take on the following appearance: on one hand there is the tendency to exercise its domination on the workers’ movement which is mainly expressed by the action of reserving revolutionary theory for the intellectuals and leaving the workers’ movement busy with economic struggles. On the other hand there is the tendency to conciliate the interests of the proletariat and those of the bourgeoisie, which is particularly expressed by bourgeois nationalism.

It’s particularly in Quebec that this process was accomplished the most quickly, and that it had the greatest influence among the masses.

Among the debates waged in the nationalist movement in the ’60’s, the debate on the relation between socialism and independence was the most decisive. All of the nationalist groups had reform programmes often proclaiming to be anti-capitalist, or anti-imperialist. The debate was crystallized around two themes. The first consisted of claiming that the independence of Quebec was a pre-condition to the future of socialism. The other put forward that the struggle for political independence and the struggle for socialism were one and the same struggle.[18]

Each of these tendencies was represented by a journal. Parti Pris, founded in 1963 by a group of intellectuals at the University of Montreal, applied Fanon’s theses on colonialism to Quebec. Its founders supported “tactical support” for the national bourgeoisie, in order to obtain the political conditions which would permit the waging of the struggle for socialism afterwards.

In opposition to Parti Pris, the journal Revolution Quebecoise, founded in 1964 by Charles Gagnon and Pierre Vallieres, was against support for the national bourgeoisie, and put forward the struggle for socialism on the basis of a working class organization.The polemic between the two journals was concretized with the creation of the Mouvement de Liberation Populaire (MLP) (Peoples’ Liberation Movement) whose manifesto proclaimed the rejection of support for the bourgeoisie, the necessity of building a revolutionary working class organization, the necessity of the Party and of a vanguard to build the Party.

At this point, we should bring a few clarifications. The concept of the “vanguard” at that time did not mean what it means today. It was not the Marxist-Leninist concept which designates the most advanced elements of the proletariat who must be rallied to create and build the party. The term “vanguard” had an elitist conception behind it. It was the “conscious” elements of the petty-bourgeoisie who had given themselves the mission of being the vanguard of the masses. The MLP was impregnated with this anti-Marxist pretension, as were the Front de Liberation du Quebec (FLQ) and the Front de Liberation Populaire (FLP).

The MLP tried to approach the workers’ movement, but it had a very short life span. On the prompting of the Trotskyists a part of the MLP passed over to the Socialist Party of Quebec (Parti Socialiste du Quebec – PSQ) – a social democratic party issued from a split in the NDP and founded by Michel Chartrand, Emile Boudreau and others that disappeared after the electoral defeat in 1966. The goal of adhering to the PSQ was to radicalize it, according to the well known Trotskyist tactic which consists of infiltrating (or creating) a social democratic or revisionist type of bourgeois party so as to afterwards try and lead it on to revolutionary positions.

The second half of the ’60’s saw a considerable widening of the social strata won over to the nationalism and independence of Quebec. Thus, when in 1967, Rene Levesque left the Liberal Party, slamming the door behind him, he represented and brought out with him an entire segment of the Quebec bourgeoisie. With the creation of the Mouvement Souverainete-Association (MSA) and its fusion with the Ralliement National (RN) itself issued from the Creditist Party which ended up in 1968 with the creation of the Parti Quebecois, the bourgeoisie really took the nationalist movement in hand. The question of supporting or opposing the national bourgeoisie was more than ever concretely and clearly posed.

It’s at that moment that certain of the more radical nationalists began turning more systematically to the workers’ movement which began making strides forward on the political scene. The development of the workers’ and peoples’ struggles at the time, led to the sharpening of the existing contradictions among these elements. And so, two very distinct currents whose influence is still being felt today within the Marxist-Leninist movement appeared. The first, whose break with the bourgeoisie was least advanced, was the current that was at the time called “social animation”. Paid and financed by various governmental organisms or by religious and “charitable” organizations, the social animators threw themselves into the organization of citizens’ committees, tenants organizations and other peoples’ organizations. The characteristic of these different committees was to bring people together to defend themselves against rent increases, the destruction of homes, health problems, debts, etc. Through these actions, the social animators sought to attain political objectives, going from “workers’ power” to supporting the Parti Quebecois. But precisely because of their conceptions of political work based on a contempt for the masses, they camouflaged these objectives. And so they quite well represented that tendency of the petty-bourgeoisie which when it approaches the workers’ movement, seeks to keep or to conquer control, and to do so, conceives of its political work as work of manipulating the masses, for, according to them, the masses... can’t understand. In opposition to this tendency, the tendency called “mass political agitation” developed. Grouped together around organizations such as the Front de Liberation Populaire, the Front de Liberation du Quebec (the 1966 tendency[19]), the Mouvement syndical politique (the political union movement), and the Vallieres-Gagnon committee (a support committee that fought for the release from prison of Pierre Vallieres and Charles Gagnon), this tendency was at the origin of the great political demonstrations in the late ’60’s: McGill Franpais (1969), against the language Bill 63 (1969), Murray Hill (1968), Anti-Congress (demonstration led against the Union Nationale which was then in power) (1969), numerous demonstrations for the liberation of Quebec political prisoners, etc... These groups also manifested an active participation in all the important workers’ struggles in these same years: construction, taxi... As opposed to the social animators, these groups were not afraid to openly present their political objectives. They contributed to the development of political debates among the masses, thus widening their political horizons, while the animators reduced these horizons to their immediate problems. However, besides stimulating nationalism, these groups were incapable of the least bit of continuity in their work, of which the bourgeoisie quickly gained control. Just like the social animators, these groups were incapable of organizing the masses on the basis of their fundamental interests.

The evolution of these two tendencies was to lead both of them to defeat. On the one hand, the social animators for whom open political action was to become a necessity, in 1969-70, united with the social democrats of the union centers, and the Trotskyists, in the electoral experience of the political action committees (FRAP)[20]. This led to a new defeat whose organizational result was the departure of the political action committees (comites d’action politique – CAP) of St-Jacques and Maisonneuve from the FRAP. We will come back to this later.

For their part, the action of groups such as the FLP and the MSP did not meet with much better results. They rallied very few workers and perpetually had to begin their actions over again. The October Crisis of 1970 confirmed their total failure. These groups were easily disorganized by the effects of the sudden and brutal repression. The repression accelerated the explosion of their contradictions and spelled their defeat.

And so, the early ’70’s was a time of great reflection for all these groups. And a short time later, out of this arose two new organized tendencies,, that of CAP St-Jacques which withdrew from the FRAP on the basis of a criticism of its electoralism, and that of the Equipe Du Journal which was at the origin of the group IN STRUGGLE!, and which took up the ideas of mass agitation and propaganda, but this time on a Marxist-Leninist basis.

The debates which opposed these two tendencies at the end of the ’60’s are rich in lessons for the current Marxist-Leninist movement. For their struggle was in fact the struggle between two conceptions of how to link up with the masses. The foundation of this debate is still of current interest because the present-day Marxist-Leninist movement is still largely composed of petty-bourgeois elements, and thus of elements who are under the influence of the ideology of their class.

What was presented in the late ’60’s as a struggle between those doing work in the working class on the sly, or in secret, and those who threw themselves into vast campaigns of mass political agitation was to reappear in 1972-73, as a struggle opposing those, who like the CAP St-Jacques, limited their work to implantation (that is, sending intellectual militants into the factories), and militant unionism, and those, such as our group, who put forward the necessity of establishing links with the working class through communist propaganda and agitation.

Or in other words, there were those who put forward that communists could only link themselves to the masses on the basis of their revolutionary objectives, and there were those who claimed that it was first necessary to link up with the masses before presenting them with objectives of the revolution. This same struggle still goes on today, but in another form. Today it opposes those who like the League, seek to radicalize the economic struggles of the masses in order to give them a political character, and those who, like us, seek to unite the working class on the grounds of the open political struggle against the bourgeoisie and its State.

We have already presented the general situation in English-Canada in the preceding chapter, by situating the role played by the Progressive Worker Movement. However it is necessary to complete this by situating, in a more precise way, the role played by certain other important groups such as the Canadian Liberation Movement (CLM), the Waffle, and the “C”PC(M-L).

As was the case in Quebec, what all of these groups had in common was to propagate an essentially nationalist line in somewhat different forms from the Quebec nationalists, given the different nature of the national question in that part of the country. For, Quebec really does suffer national oppression. It is deprived of several of the fundamental rights of nations. While Canada is a politically independent State, which does however suffer vexations at the hands of American imperialism. Something else which these groups all had in common was to put forward fundamentally petty-bourgeois positions, and to recruit the great majority of their members from this class.

The Canadian Liberation Movement was formed in Ontario in 1969. It produced and distributed a newspaper, New Canada, and even had its own publishing house. Its influence went far beyond Ontario to the West of the country. This group, which was able to develop thanks to the decline of the PWM in the late ’60’s, shared the same nationalist line. However, in opposition to the PWM, there was never any question, in its official line, of basing itself on Marxism-Leninism, nor was there question of the necessity of a proletarian Party. For a fuller understanding of the line of this group, we refer the reader to the pamphlet “One step backwards, two steps backwards”, by Harry, (reedited by IN STRUGGLE!, April, 1977).

The Waffle corresponded to a somewhat different situation. It was a nationalist tendency formed within the New Democratic Party around the Watkins Manifesto. There was never any question of revolution for this group, not even a “national” one. In fact, it reflected the broad denying of the nationalist influence within social democracy. It was particularly strong in the early ’70’s in provinces like Saskatchewan and Ontario where the NDP constituted a major political force. However, once again, internal contradictions sharpened. One part of the movement became the nationalist caution of the completely corrupted leaders of the NDP while another fed into the various Trotskyist sects in English-Canada. Yet another, not very numerically important, recently rallied to the Marxist-Leninist movement. We should note that two Marxist-Leninist groups from Regina, (the Regina Communist Group, today rallied to IN STRUGGLE!, and the Regina Marxist-Leninist Collective, today rallied to the League) came out of the Waffle movement.

The “C”PC(M-L) merits particular attention. First of all because it still exists today, although the recent successes of the Marxist-Leninist movement have reduces its influence. But also because its work of sabotage continues to produce negative effects among the masses, and above all, because at a certain epoch, it was the only one of these groups to openly declare itself as being Marxist-Leninist.

The “C”PC(M-L) had its origins in a student group called the Internationalists formed in 1963 by Hardial Bains. With a leftist and ultra-leftist appearance, the “C”PC(M-L) always was and still is today, a fundamentally counter-revolutionary group.

In 1970, when it became a party, the “C”PC(M-L) self-proclaimed itself the Party of the working class. This self-proclamation was a serious act. For communists, the question of the supreme organization of the proletariat, its single party, constitutes a question of principle. You don’t create a party... because it’s necessary to create the party! You create the party when certain historical conditions have been met. You create the party when you have developed the programme of the revolution in your country, when you have united the Marxist-Leninists around this programme, and when a significant part of the advanced elements of the proletariat have rallied to this programme.

Even if it is clearly irrealist to specify these preliminary conditions with precision and in detail, it is In any case, absolutely essential that the creation of the Party be preceded by work of this nature, and further, that the creation of the Party be a factor which permits the development of this work.

However, this was not the case with the creation of the “C”PC(M-L).

The “C”PC(M-L) never established a communist programme, all of its theoretical work was reduced to the eclectic ill-assorted, illogical reproduction of bits of quotes from Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao TseTung and today Enver Hoxha. The only common point in the dozens of lines which it elaborated throughout its history, (in effect, the “C”PC(M-L) changed political lines whenever the wind changed), is their opposition to proletarian revolution. In fact, ail of these “political lines” were able to agree about one thing: the path of the revolution in Canada goes by bourgeois nationalism! Through all of its clothing changes, the “C”PC(M-L) never forgot the one stable point in its line: its conciliation with the Canadian bourgeoisie. Once again today, while it displays virtuous indignation in its press against those who support the “three worlds theory”, it publishes documents which contain the basest and most obvious pearls of social-chauvinism:

“1- The principal contradiction is between American imperialism and its lackeys in Canada and the great majority of the Canadian people. That is the principal contradiction which plays the decisive role in the forward movement of society.

2- The second contradiction is between the monopoly capitalist class and the Canadian working class. This fundamental contradiction manifests itself in the form of the struggle between the American imperialists and their Canadian lackeys (sic) on one hand, and the Canadian people on the other...”[21]

In effect, instead of a communist programme, we have something that is totally devoid of a class point of view and bathing in bourgeois nationalism, which soothes the Canadian monopoly bourgeoisie. Because a programme like that assures it of the proletariat’s support for its struggle to be “competitive” in the international arena and to rival all the other imperialist countries, including American imperialism. At the same time, it is assured that the political struggle for the long term interests of the proletariat will be completely drowned out and left aside in the interests of the so-called mass anti-imperialist struggle. This was caricaturally shown by the list of “13 mass revolutionary movements” which the “C”PC(M-L) drew up, with point 4 being a vague reference to the “the struggle against capitalist exploitation”:

“There are thirteen revolutionary movements within the Canadian people:

1- the struggle of the Canadian people against imperialist domination and control and to support the national liberation struggles of the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America;

2- the national liberation struggle (sic) of the Quebec people against Anglo-Canadian colonialism (re-sic);

3- the just struggle of the Native peoples for the restoration of their hereditary rights;

4- the fundamental struggle of all workers against capitalist exploitation and wage slavery;

5- the fundamental struggle of all working women for social, political and cultural equality;

6- the economic struggles of workers for better wages and working conditions;

7- the struggle of the unemployed to obtain jobs;

8- the struggle of all workers to politically organize themselves in the workplace;

9- the struggle of the fishermen and the farmers against foreign monopolies;

10- the revolutionary struggle of all immigrants and national minorities against racial discrimination and repression;

11- the struggle of working youth against capitalist cultural aggression;

12- the struggle of the students against the decadent capitalist educational system;

13- the struggle of all progressive and democratic people against the fascist laws and regulations and repression by violence”.[22]

As you can see, it wasn’t the Canadian Communist League (M-L) who invented the “shopping list” of contradictions and tasks!!!

This is why it is correct to say that the “C”PC(M-L) is a caricature of a proletarian Party, that historically it has been the groups which painted bourgeois nationalist ideology red in order to better trick the masses and to corrupt the Canadian revolutionary movement from within. A Marxist-type vocabulary and the shameless usage of the Chinese Revolution and its great leader Mao Tse-Tung served to paint it red until the time when the young Marxist-Leninist movement broke with reactionary nationalism and unmasked this group of counterrevolutionaries for what it is – a gang of active agents of the bourgeoisie within the Marxist-Leninist and workers’ movements.

During the 1970 October Crisis, this Party even went so far as to openly advocate petty-bourgeois terrorism. Its practice and its conception of unity have always consisted in seeking the best means of swallowing up the groups that is meets on its path, even to the point of infiltrating them, and practising “entrism”. (A tactic widely used by the “C”PC(M-L) at one time, which consisted of secretly infiltrating into political groups and causing them to break up).

Its practice has always been one of dividing the Marxist-Leninist forces. Finally, except for a few students who venerated its leader, the “C”PC(M-L) never rallied the vanguard of the working class. What characterizes the “C”PC(M-L) on the question of the creation of the Party, is the inversion of the relation which it establishes between the political objectives of the working class and the organizational forms that it establishes to achieve them. For communists, form is always subordinated to the content; organization must serve ideology. For the “C”PC(ML), on the contrary, the political line was reduced to organizational tasks:

“Political line is the sum-total of the tasks an organization sets for itself in order to advance the over-all general tactical and strategic work.”[23]

The entire history of the “C”PC(M-L) is the expression of the ultra-leftist tendency of the petty-bourgeoisie which seeks to exercise its hegemony over the proletariat, and which in fact, doesn’t recognize the principle proclaimed by Marx and Engels in their Manifesto... “that the emancipation of the workers is the work of the workers themselves”, that is, which doesn’t recognize that the masses must have their own experience and wants to make revolution in place of the masses.

The existence of the “C”PC(M-L) is an important obstacle to the central task of building a really proletarian Party. In English-Canada, the social-fascist manoeuvres of the “C”PC(M-L) have pushed circles into localism and caused them to turn in on themselves, and have been an obstacle to the undertaking of the task of party building. And generally, they have developed a repulsion for Marxism-Leninism among the masses. Canadian Marxist-Leninists must pursue the criticism and struggle against the “C”PC(M-L). First of all because it still exists and continues its undermining work. But also because it’s urgent that we protect ourselves against its deviations which risk reappearing in other forms. At the present time, there is a part of the movement which tends to adopt attitudes and a point of view similar to those of the “C”PC(M-L).

For, after having self-proclaimed itself the organization of struggle for the Party, the Canadian Communist League (Marxist-Leninist), who, in passing, has as one of its founding groups the Mouvement revolutionnaire des etudiants du Quebec (Revolutionary Movement of Quebec Students), which originated, in part, from a split in the “C”PC(M-L), is heading straight to its self-proclamation as the Party of the working class. The sectarianism that the League has manifested with regard to the Marxist-Leninist movement, its tendency, in the last while, to promote its organization before the masses in an unprincipled manner, not to talk of its habit of substituting itself for the masses, as it is currently doing in the flourmill workers’ struggle, all of this originates in the same class position as that of the “C”PC(M-L). And if there is no serious rectification, all of this can only lead to the same result – the creation of another counter-revolutionary Party.

The Third Conference of Canadian Marxist-Leninists which was held last September 9,10, and 11, gave us the opportunity to note that Bolshevik Union (BU) has more in common with the “C”PC(M-L) than with the Canadian Marxist-Leninist movement. During those three days, BU’s militants adopted a splittist attitude which was, on all points, similar to that of the “C”PC(M-L). They sought to antagonize the current differences within the movement rather than to resolve them by frank and open ideological struggle. They refused to debate with those who recognized the “three words theory”, and were content to label them “revisionist renegades”. They openly sought to sabotage the debates by attacking IN STRUGGLE! on the basis of lies and by centering the conference’s attention on secondary questions. They systematically refused to develop one word of solid argument against the “three worlds theory”. And furthermore, just like the “C”PC(M-L), BU adopted a tailist attitude with regard to the line of the Party of Labour of Albania, and used the prestige of that glorious Party to justify its splitting and wrecking actions.

The struggle against bourgeois nationalism in English-Canada had its start in the late ’60’s. In particular, it was crystallized around the Simon Fraser Student Movement, a movement of student youth in British Columbia, which criticized the PWM for having put the exploited at the mercy of the bourgeoisie, and which was opposed to the CP because of its too obvious conservatism. The youth movement of this epoch produced many different organizations which opposed bourgeois nationalism. Among them, there was the Partisan Party which supported the necessity of building a single Marxist-Leninist Party on a Canada wide scale. However, the Partisan Party was waylaid by the “C”PC(M-L). And that spelled the defeat of the anti-nationalist movement in English-Canada.

The following years, that is from 1972-77, were to see a certain development of bourgeois nationalism in English-Canada, particularity in the Vancouver region. Groups such as the Western Voice and the Vancouver Study Group (VSG), were formed, set up by the ex-militants of the PWM. These groups had militants who were active in the union movement where they defended an essentially nationalist line: the struggle for the canadianization of the unions seen essentially as a struggle to democratize the unions. Even if these groups weren’t very big, even if the VSG, for example, never did political work within the workers’ movement on its own basis as a group, their line carried considerable weight, given the active role played by their militants and the prestige that certain of them had among the masses.

The influence of bourgeois nationalism will only be questioned with the appearance of a Marxist-Leninist movement, which was able to succeed where the youth movement had failed.

The 70’s began with an exacerbation of the contradictions in the world which led to a deepening of the general crisis of imperialism. The oppressed peoples had the wind in their sails. In particular, the heroic struggle of the Vietnamese people won international support, and the serious defeat which this small people inflicted on American imperialism accentuated contradictions within the United States themselves. The invasion of Czechoslovakia by Soviet troops, in 1968, discredited the USSR in the eyes of the peoples, and revealed its real imperialist nature. As of then, a new superpower had made its entrance onto the world stage and its voracious appetite and rivalry with American imperialism, became a threat for the security of the peoples.

The firm principled struggle led by the Party of Labour Albania and the Communist Party of China against modern revisionism, led by the pseudo-communist party of the Soviet Union, the successes in the building of socialism in Albania and China, and the resounding success of the Great Cultural Revolution in China rapidly increased support for the socialist countries among the peoples of the world. This support and the prestige of the socialist countries resulted in the expulsion of Taiwan from the United Nations in 1972 and triumphal entry of China.

In the industrialized capitalist countries, the accelerated rise in the cost of living and in unemployment, increased the anger of the workers’ movement. In Quebec, unlike in the ’60s, it is no longer the petty-bourgeoisie which is to be found in the heart of the great mass movements. Rather, it is the working class. During the conflict at La Presse in 1971, more than 10,000 workers took to the streets to support the strike struggle.

Strikes succeeded one another as if by chain reaction. They were longer, more frequent and more militant. The vigour of the workers’ movement was so great that the union centers published Marxist-sounding social-democratic and nationalist literature. The QFL denounced the State as “the instrument of our exploitation”. The CNTU launched an anti-monopoly campaign in which it explained the volume of American imperialist penetration in Quebec. Louis Laberge, that anti-communist and champion of business unionism, completely sold-out to the bourgeoisie, began threatening that he was going to “break the regime”, right in the middle of workers’ meetings.

The growth of the workers’ movement reached a high point with the civil-servant and semi-public workers’ Common Front strike in the spring of 1972. Following walkouts by more than 200,000 workers across the province, the bourgeois State tried to put down this movement by condemning Yvon Charbonneau, Louis Laberge, and Marcel Pepin, the leaders of the three large union centers in Quebec, to a year in prison. The answer from the workers’ movement, and in particular from the industrial proletariat, was lively and quick. Across the province, factory occupations and occupations of entire cities multiplied. The heroic example of the workers of Sept-Isles, who completely paralyzed their city, resounded across the province.

And so, the early ’70’s witnessed once again extremely difficult economic struggles. Despite the still important weight business unionism, social-democracy and “militant” unionism often linked to bourgeois nationalism, were the dominant tendencies in the workers’ movement. It’s in this context that the Marxist-Leninist movement appeared in Quebec with the publication of the pamphlet For The Proletarian Party, in 1972 and with all that followed, that is, the formation of the Equipe du Journal around the line developed in the pamphlet. From that moment on the Equipe saw to the production and distribution of the newspaper IN STRUGGLE! and began concrete work to apply the line put forward in For The Proletarian Party. To understand what an important step forward For The Proletarian Party was, we must situate it in the historical context the period and examine what was dominant in the progressive groups at the time.

The Trotskyists dominated the FRAP but were quickly loosing ground, although they had a certain influence in the citizens’ groups and in certain union centers in Montreal. The “C”PC(M-L) (or the “C”PQ(M-L) which changed names in the most opportunist manner possible, depending on whether the situation was favorable or not to nationalism, was a marginal phenomenon, but had some influence in a few citizens’ groups, unions and schools. It was their “leftist” period, one of raging battles with the police where the “C”PC(M-L) responded tit for tat. In the student movement many tendencies were to be found, including the Trotskyists, the “CPC(M-L)”, the student sector of the Political Action Committees (CAP) St-Jacques and Maisonneuve, and the MREQ, which was Marxist-Leninist in name, but whose practice was far from being consistent. Instead of attacking the central task commanded by a creative and rigorous application of Marxism-Leninism, and by the concrete situation of the workers’ movement, that is the reconstruction of the revolutionary Party of the proletariat, the militants of the MREQ limited their activities to what they called, at the time, the struggle against the capitalist school and support for the working class and anti-capitalist struggles. There were also a few Marxist-Leninist study circles, with no unity between them and a few progressive workers’ committees. As for the relations between this movement in Quebec, and the movement in Canada, there was voluntary ignorance on both parts, which clearly shows the weight of bourgeois nationalism.

Within the progressive movement, the two most influential groups at the time were the CAP St-Jacques and the CAP Maisonneuve. The two CAPs merged in 1972. Their unity and fame were achieved during the struggle within the FRAP in December, when they opposed the social-democrats and Trotskyists. They demarcated from the electoral experience of the FRAP. They criticized the FRAP for not being well rooted in the working class and for not sufficiently educating its militants to work within the proletariat. These criticisms are to be found in the manifesto published in December 1971 by the CAP St-Jacques, This manifesto entitled For an autono-mous political organization of workers was much talked about In the progressive milieu of the time. The manifesto identified American imperialism as the principal enemy of the Quebec people. It put forward the necessity of an autonomous organization of Quebec workers to wage the struggle for the national liberation of the Quebec people and for “socialism.” (One did not yet speak of the dictatorship of the proletariat). To do this, the manifesto proposed the setting up of groups of workers, in the community or in the workplace, which would be the basis of a future organization of workers. As well, it insisted on the necessity of diving the militants a Marxist education. (Marxism-Leninism was presented as a “tool”).

The manifesto arrived at a period of intense mass struggle which enabled the CAP St-Jacques and Maisonneuve to develop. As in all periods where there is an intensification of class struggle, the mass movement forces the clarification of positions and accelerates the polarization. At that particular moment, the Common Front strike of 72, put on the agenda the necessity of uniting the CAPs to centralize their political work. Two lines were crystallized in the debate which was held during and after the struggle.

The first line considered that, not to intervene in the struggle, was unthinkable. It proposed to develop a class analysis of the interests at stake in the struggle so as to be able to undertake propaganda work, counting on the militants who were implanted in factories, and assuring a presence on the picket lines. Those who held this line affirmed the necessity of uniting among themselves, and of uniting the forces in order to centralize the work. The line of the opposition had its stronghold in the work sector of CAP St-Jacques[24]. The leaders of the Work Sector completely refused to intervene in the class struggle on the pretext that the Common Front struggle was too vast for the CAP, that the militants were hardly experienced, and that since they had been implanted for such a short time, it was asking too much of them. The work sector supported the idea that the militants should educate themselves before acting, by means of their implantation in the factories, by the carrying out of inquiries and by developing their local work. Once the militants were educated, then the real political work could take place. Consequently, the Work Sector opposed the centralization by the CAPs because that would lead the CAPs to turn inwards on themselves. The Work Sector proposed the decentralization of the CAPs into different nuclei of militants, to better penetrate the working class. Briefly, the Work Sector, opposed the unity of the CAPs, and advocated local work and amateurish organizational forms.

The work sector’s line wanted to stimulate the economic struggles by union activism and to organize the proletariat around economic struggles. The political struggle was reduced to the struggle to democratize the unions. The Work Sector’s line consisted in no more no less than promoting local work and refusing the revolutionary political struggle of the proletariat. Furthermore, in practice, these militants rejected the idea of Marxism-Leninism as a guide for action. They conceived of theory as an historical and economic analytical grid for militants, and that is all! This rejection of revolutionary theory was also expressed in the refusal of debates, which characterized the work sector. In other words, the work sector’s line, when it came to party building, consisted of doing economic organizational work among workers, while they educated their militants by lectures.

This line is fundamentally economist because it limits the working class to the economic struggle and reserves theory for the intellectuals. It is certainly not with this line that the proletariat will advance on the road of the revolution.

The work sector’s line once again took up the line of social animation which had reigned in the late ’60’s within the citizens’ committees in St-Jacques, which gave birth to CAP St-Jacques. Just like the social animation line, the positions of the Work Sector consisted of saying that the working class wasn’t ready for political action and that consequently it was first necessary to prepare the workers for political struggle by making them wage struggles which concerned their most immediate needs. Briefly, the work sector’s line was profoundly marked by the same “workerist” point of view, and the same contempt for the masses, as was the social animation current.

Despite the sectarian and putchist methods of the leadership of the work sector, the line of the work sector was the most influential line in the progressive movement, at the time that For The Proletarian Party appeared in October ’72.

The appearance of For The Proletarian Party was the most articulated and solid opposition to the economism which reigned at the time in the work sector. For The Proletarian Party affirmed the necessity of adopting the proletarian ideology, that is, Marxism-Leninism, as the science and the arm of the proletariat in its struggle against the bourgeoisie. It called on the necessity of struggling for the creation of a Marxist-Leninist proletarian Party, having as its objective proletarian revolution and the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat. To do this, it was necessary to develop the ideological struggle against bourgeois ideology, in particular bourgeois nationalism and reformism, by wide-scale propaganda and agitation, by rallying conscious workers, and by uniting Marxist-Leninists.

For The Proletarian Party constituted a qualitative leap forward among the progressive forces at the time. The affirmation of the “PROLETARIAN” character of our tasks, in itself, marked an important rupture with the use of such terms as “salaried workers” or other expressions of the same nature. The fact that Marxism-Leninism was no longer considered to be an analytical grid, but a science and a guide for action, permitted the masses to grasp Marxism-Leninism and to demarcate from the economist point of view of the CAPs on the question.