Red Medicine: Socialized Health in Soviet Russia

IT HAS already been noted that in Russia social insurance differs from that of any capitalist country in that the workers do not contribute to the funds. No contributions are paid by them week by week as in other countries, but necessarily it is the funds chiefly created by their work which provide for their insurance. In each factory or other institution there is a Social Insurance Bank, in which the contributions from the industry or institution to the insurance fund are deposited. These contributions are calculated on a per capita basis according to wages. The bank is controlled by a committee of the workers, without any representative of the administration. This committee is elected at trade union meetings. The Central Office of Social Insurance is at Moscow, in the All-Union Commissariat of Labor. The director of this central office is elected by the Council of the People's Commissariat, on the recommendation of the Central Committee of Trade Unions.

It must be noted also that although "all workers are included without exception," this does not apply to the adults and their dependents who are deprived of their civil rights. The number of these is estimated by Calvin B. Hoover(1) at eight millions, including their dependents, but, as we have said, it is much less than this (see page 122) . The "deprived" persons include former landlords, bourgeoisie, nobles, Tsarist officials, merchants, kulaks, and Tsarist army officers. Social insurance does not as yet include the peasants, who form the vast majority of the population. These are, however, partially relieved from taxation; and since 1930 the position of the disfranchised classes enumerated above has been somewhat ameliorated. In the main it still remains true that deprivation of civil rights means also that those deprived are not entitled to a ration card or a cooperative card, or to be registered on the regular unemployed list, or to attend school above the school of the "second step."

The details of social insurance are set out in Dr. Hoover's work, and a useful summary is contained in the official Guide-Book to the Soviet Union. The provisions for insurance come under six headings — sickness, permanent incapacity, maternity, unemployment, old age, and burial.

Full wages are paid during leave of absence because of illness; during absence from work while quarantined because of infectious disease in the family of the insured; or during absence while nursing a sick member of the insured person's family. The full wages during incapacitating illness continue until complete recovery or until the disability becomes permanent. Sick leave after ten days is only continued after consultation between the doctor treating the case and the medical referee. If difference of opinion arises, the case is referred to the medical supervisory Committee.(2) There are thus ample safeguards against malingering, which is said not to exist.

During illness, whether incapacitating or not, medical services are given. These are not administered by the insurance department, but by the Commissariats of Health or the Local Boards of Health. These services include hospital treatment and specialists when needed.

The dependents of the insured, all unemployed persons, and all trade unionists are similarly entitled to free medical treatment, including the supply of drugs.

In addition there is very large provision of rest homes, sanatoria, and beds at health resorts. Three fourths of the beds in these are reserved for industrial and transport workers. Certain rest homes are maintained by the trade unions. The funds for free medical service are obtained to the extent of to per cent from local funds. A further demand of 3 per cent may be made by the trade unions. Social insurance funds provide the largest share of medical expenses. Sanatoria are supported, some of them by social insurance and some by public health funds.

If permanent incapacity occurs, a pension is given, the amount of which varies with the degree of incapacity. It is more liberal when the incapacity is due to industrial accident or to disease incidental to the insured person's occupation. It varies from two thirds to

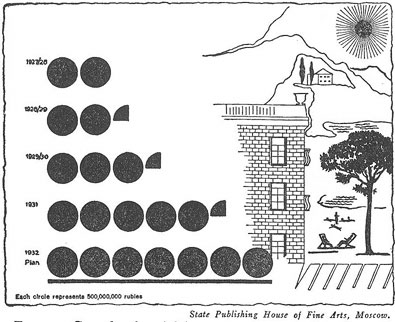

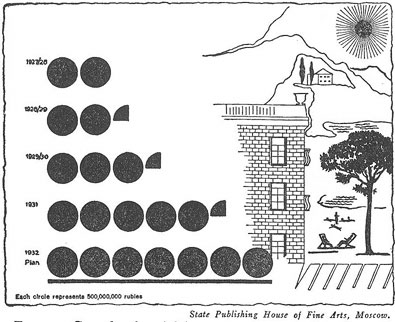

FIG. 3. Growth of social insurance appropriations in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics since 1927-1928. The figures for 1932 are estimated.

one third of the person's regular wage. A similar system applies to pensions for dependent widows. If permanent invalidity occurs after the age of fifty, the worker must qualify for pension by proving that he has been employed during at least eight years preceding the beginning of this invalidity.

Women employed in manual work are entitled to eight weeks, and women employed in non-manual work are entitled to six weeks, of rest at full wages before confinement, and the same benefit after confinement. They are entitled to a single bonus, for infants' clothing, of one half of the mother's wage when the birth is registered, and afterwards, during nine months, to a monthly nursing benefit of one fourth of the average monthly wage. These benefits accrue also to unemployed women and to the wives of unemployed men. The benefits given in nursing homes for infants and children are stated in Chapter XII.

There was social insurance prior to 1913, and the fund then accumulated, we were informed by Professor Landis, the head of the Institute of Public Health in Moscow, still exists. It is now being utilized for the provision of creches and similar institutions. For skilled workers who have been at the place of registry for nine months about 30 per cent, and for unskilled workers 20 per cent, of the average working wage is paid during a period of six months when unemployed.

The statistics of unemployment do not include expropriated kulaks and many others, and, as previously noted (pages 119 and 122), statements as to the present absence of unemployment have an application which is restricted to this extent. No person can claim unemployment pay because he cannot get the work for which he was trained. It is conceivable, therefore, that a lawyer, for instance, may be required to work as a laborer. We were repeatedly informed there was no unemployment in towns, a statement which is probably true for efficient workers coming within the scope of the insurance scheme.(3)

Funeral expenses are paid in the case of insured persons, or of those in recei of pensions or unemployment pay, and of the dependents of these.

Pensions for old age and for dependent widows are also provided. According to G. R. Mitchison (in one of the Twelve Studies in Soviet Russia) all who have been employed for twenty-five years get old-age pensions at the age of sixty to the amount of half their wages for their last year of employment. Workers in mines and in textile and chemical trades can get their pensions at the age of fifty and besides can continue to work at full wages if they like.

These extensive benefits call for vast funds. The total contributions made by industry naturally vary according to the wages paid, and, on the average, represent a tax of nearly 18 per cent of total wages. The rate of contribution varies from 5 per cent for home workers to 22 per cent for workers in unhealthful or dangerous occupations, we are informed by Dr. Roubakine. According to Chamberlin (in Soviet Russia) the total expenditures for insurance and miscellaneous welfare are calculated at 32 per cent of the wage bill, but this includes also activities not coming within the range of insurance benefits. Mitchison, in the work quoted above, says that the contributions average about 14 per cent of the wages paid. But although the exact percentage is doubtful, the insurance contributions of industry are much larger than those made in other countries.

Insurance is organized on a unified and territorial basis, including insurance against accidents as well as sickness and unemployment. Transport and railway workers are under direct All-Union jurisdiction, and Public hence are an exception to this territorial arrangement.

The preceding summary makes it clear that social insurance plays an important part in the economy of Russian life in towns. Its distinguishing feature is that the cost falls on the employer whether this be the state, or a cooperative body, or any other employer. This statement applies completely to monetary benefits. Part of the cost of the medical part of insurance is derived from general taxation.

It has already been noted that deprived classes are excluded from insurance benefits, and that its benefits have not yet been extended to peasants.

With these important exceptions it appears that, in Russia, greater security is being given against economic and health hazards than in any capitalist countries. The U.S.S.R. compares very favorably with the United States in this respect, but it will be remembered that there is a vast difference between the wages in the two countries.

The aim of insurance in Soviet Russia, as elsewhere, is to replace charitable relief by aid to which the worker is entitled, and, subject to the exceptions named above, this aim is being fulfilled. There is no charitable relief in Russia.

(1) In The Economic Life of Soviet Russia. New York, The Macmillan Company, 1931.

(2) See Compulsory Sickness Insurance, Geneva, League of Nations, 1927.

(3) Similarly Dr. Hugh Dalton in one of the Twelve Studies in Soviet Russia (London, Victor Gollancz, 1933) made by a group of English Fabian socialists, says "for the present at least unemployment has been planned away."