Awakening to Life. Alexander Meshcheryakov 1974

The rearing and teaching of the deaf-blind is carried out in accordance with special guidelines and learning programmes elaborated at the Institute for Research into Physical and Mental Handicaps, and the work is divided into two stages for a pre-school and school period.

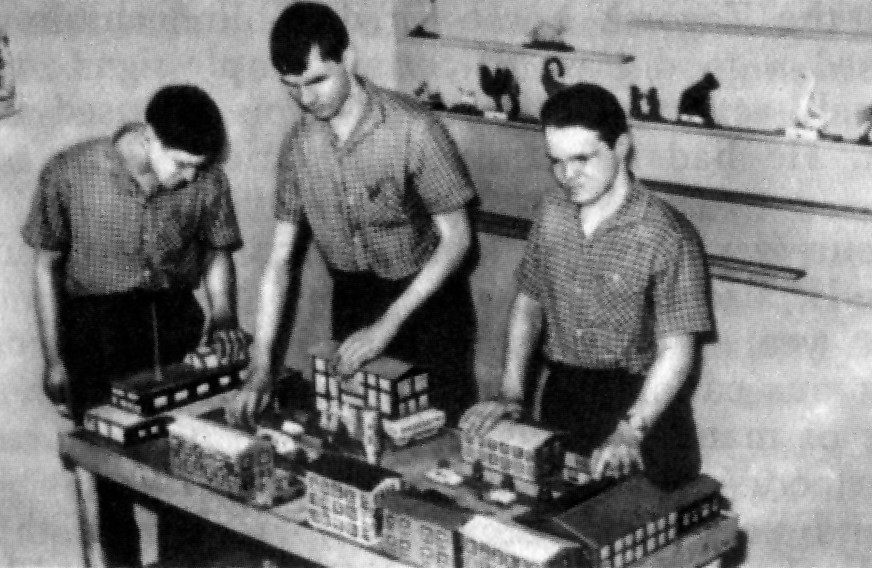

In the academic year of 1969-1970 special working groups for pupils over sixteen were set up. The pupils in these groups were to complete training in a specific trade suited to their particular mental and physical capacities.

In the home for deaf-blind children there is also a group of pupils following the syllabus stipulated for classes 5-10 in ordinary schools (i.e. for normal pupils aged between 12 and 17). In accordance with the findings of a teacher’s committee and on recommendation from the relevant research unit at the Institute and with special permission from the RSFSR Ministry for Social Maintenance (under whose jurisdiction the Zagorsk home falls) some of them are allowed to stay on at the home after the age of eighteen for a further period during which they can complete their secondary education and be prepared for university entrance.

Then there is a third group of pupils at the home consisting of deaf-blind children suffering from severe mental retardation, who taken on so that educability of children with multiple handicaps might be assessed.

The pre-school stage in the education of deaf-blind children is aimed at teaching children habits of personal hygiene, self-care skills, the art of speech through mime and gesture and certain elements of verbal language in the form of individual dactylic words.

The length of this stage of instruction depends upon the child’s level of development at the time when he comes to the home and the nature of the disease which robbed him of his sight, hearing and speech. Children who have been given essential basic training in their homes (some in accordance with recommendations from members of staff at the Institute) are able to start their course of instruction at the school, rather than the pre-school stage, or to complete the pre-school programme within a year or two; the other children who have not been given this basic training by their families, whose training has been neglected and who suffer from additional handicaps as well (such as motor handicaps, general physical weakness, etc.) may take four or even five years to complete the pre-school programme.

The teaching of deaf-blind children is embarked upon at the earliest possible age. In accordance with the “Regulations for a Home for Deaf-blind Children” issued on June 14, 1968, children can be enrolled at the home any time from the age of three onwards. However, with a special dispensation, one child even came to us at the age of two. The earlier a deaf-blind child’s instruction begins the greater results in his development can be achieved. When a teaching programme is drawn up for such a child, teachers need to start out not from his age but from the level of his development: if a seven or even a ten-year-old child has not reached the required level of mental and general development, his learning activities still have to follow the same programme as that of children as young as three or four.

Towards the end of the preparatory stage of education a child has to be trained to follow a time-table, possess skills of self-care and orientation in space, to be able to speak using sign language and certain elements of verbal speech (finger-spelling, to play model from plasticine and construct simple objects found in his environment from the components of a construction kit, master skills necessary for engaging in joint activity in the household (washing up, clearing up the play corner, tending indoor plants, etc.), learn to do morning exercises and special P.T. routines (step over sticks, take small jumps, climb up on to a chair, crawl under a string or rope, etc.).

During his instruction at this preparatory stage a child comes to form images of the objects around him and to learn the functions of these objects, which is the vital prerequisite for his subsequent mastering of verbal language and for his transition to the school stage of his learning programme.

In the academic year 1969-1970 there were two groups of children at the home at this preparatory stage. The first group consisted of four children: Valery S., Katya L., Oleg P., and Frol I.

The relevant details from these children’s backgrounds are as follows:

Valery S. came to the home when nearly four. His diagnosis read: deaf-mutism, neuritis of the acoustic nerves resulting from intracranial birth trauma, and cataract in both eyes; some residual sight the degree of which cannot be established. Examination of his auditory sensitivity using tonal audiometry revealed a loss of hearing in the speech range of frequencies (500-4,000 Hz) of between 85 and 95 decibels.

Before coming to the home the child had not been used to a regular time-table, he could not find his way about and was not used to looking after himself in any way: he could not use the pot, or eat properly, he threw toys away and could neither use nor understand any signs.

Valery was taught to follow a regular time-table and some of the basic self-care skills. He learnt to use a spoon properly at meals, to help his teacher when the latter was dressing or undressing him. The first few months at the home showed that he responded successfully to lessons in the basic skills of self-care.

Katya L. left her home to come to us at the age of four. Her diagnosis read: neuritis of the acoustic nerves of unknown etiology; deaf-mutism since the age of two, and a developing cataract in both eyes. Reduced hearing in the speech range of frequencies of 70-80 decibels.

The little girl had not been taught to keep to a regular time-table. She had no self-care skills. She could hold a spoon and with a little help from her teacher was able to use it for eating. If she took a dislike to any food, she used to throw it all out of her plate on to the table and the floor. She actively resisted the people who dressed and undressed her. She had not been toilet-trained.

Frol L came to the home at the age of six and a half. His diagnosis read: congenital damage to the central nervous system, deaf-mutism, underdevelopment and atrophy of the optic nerve in the right eye, leucoma of the cornea in the left eye; some degree of residual vision, that could not be established. Hearing loss in the speech range of 70 decibels.

At home everything had been done for the boy by adults. When he came to us he had not been able to find his way about at all despite his residual vision. He had not acquired any skills of self-care whatsoever. He did not know how to play, used to throw his toys about, understood no signs and had no recourse to them himself.

At the home work was undertaken straight away to teach the boy to find his way about, to acquire skills of self-care, normal habits of everyday behaviour and play, and to learn to make signs.

After the first five months of his first year at the home certain advances in the child’s development were to be observed. The boy had learnt to undress almost independently (all that was required from the teacher by this stage was the initial stimulus for him to start on the task) and could complete certain operations by himself when it came to dressing as well (for instance, when the teacher started putting on his stockings he would pull them up the rest of the way). He learnt to hang the clothes he had taken off over the back of his chair (whereas at first he had just thrown them on the floor). He would attempt to straighten out his bedclothes when it was time to get ready for bed. With regard to playing the boy had only grasped the external aspect of the activity: for instance, he used to lay a doll in the toy cot and place all the blankets, pillows and sheets on top of her. He had not vet grasped that toys were real objects in miniature. So far the boy had been unable to take in exercises designed to promote sensorimotor development and refused to participate.

Oleg P. joined the home at the age of six. His diagnosis read: loss of speech and hearing after meningoencephalitis at the age of one year and seven months; cataract in both eyes. The child had gone blind at one year and eleven months but when he had been operated on at the age of three (right eye) and then four (left eye) his sight had been partially restored. His hearing loss was 75 decibels.

It was Oleg’s mother who began to teach him self-care skills. When he came to the home he was able to eat with a spoon, dress and undress himself with only very little help, and play with toys: he could rock a doll and push a toy car along. He made no attempt to communicate through signs: when he needed something he would take an adult by the hand and lead him or her over to the relevant object.

In the space of three months at the home he had learnt to order his day by a regular time-table, to go to the lavatory on his own and use the toilet properly, to wash his hands and face with soap, to wipe his hands and face after a meal with a napkin, to dress and undress, fasten and unfasten buttons.

The boy was also given special learning exercises, such as sorting objects according to shape and size, assembling and taking apart towers and matrvoshka dolls. In those early months he also learnt to understand certain signs such as eat, sleep, lavatory, dress, undress, although he did not make use of them on his own as yet.

Oleg made good progress in learning to play in the toy corner. With a certain amount of help from his teacher, he could dress and undress a doll, put it to bed and “feed” it, using toy crockery and furniture. All these activities were accompanied by corresponding signs, of which the boy was beginning to understand an increasing number.

Their first months at the home had revealed these children’s capacity for development.

The learning programme for this group of children incorporated the following points:

1. Further Habituation to Their Daily Time-table.

2. Orientation Skills. The children were to be helped to form a correct conception of the arrangement of objects in their room, the corridor, the bathroom, the cloak-room and the dining room; to learn to make their own way to the dining room and lavatory; to learn to distinguish between their own and others’ clothes; to get to know their own place in the dining room and at the work-table.

3. Formation and Refinement of Self-Care Skills. The children (Valery S. and Katya L.) were to be taught to use the pot on their own, to cooperate with the adult dressing and undressing them, to wash their hands on their own, to feed correctly and to clear their plates and cutlery from the table after a meal (Oleg P. and Frol I.).

4. Learning to Play. The children were to be taught to correlate toys and real objects and to learn what to do with toys.

5. Development of Communication. The children were to be taught to understand and denote through signs activities forming part of the day-to-day time-table (eating, sleeping, dressing, undressing, going, washing, and using the toilet), to be taught signs in the course of their games (doll, toy furniture, toy crockery, etc.), to understand request signs such as Bring-me-the-ball, doll, cup, spoon, etc., to develop active use of signs in learning games (such as “What doll is missing?”), to refer to their teachers and other children by the initials of their first names (finger-spelt initials that is).

6. Sensorimotor Development. The children were to be taught to pile up the rings of a sorting pyramid on the central rod, to sort sticks and cubes into different boxes and to thread beads on to a string. They were also to carry out special exercises in order to prepare them for learning to communicate using Braille and manual alphabet; to learn to imitate finger configurations, to group together cards on to which are stuck cardboard circles representing the various Braille letters, to model simple objects. They were to develop their movements in special exercises and action games.

The second group of children at the preparatory stage in their education programme were three little girls – Rita L., Lena G. and Elena B.

Rita L. came to the home aged two years and eight months. Her diagnosis read: congenital deaf-mutism, congenital cataract in both eyes, residual vision insofar as sensitivity to light was retained. Loss of hearing in the speech range of frequencies of 80-85 decibels.

When Rita arrived, she had no self-care skills at all. During her first eight months, she learnt how to eat on her own, to use the pot, to dress and undress, to hang up her clothes tidily, to wash herself using soap, to dry herself with a towel and to hang it up in the appropriate place afterwards, etc. Rita learnt to play with toys: she learnt how to put a doll to bed, to dress, undress and feed it, to take part in role-playing games with the other girls in her group, although admittedly she usually played the passive role of “child” who had things done to her. In the course of special learning exercises she learnt to assemble and take apart sorting pyramids or matryoshka dolls, to group together various objects according to their size or shape. With the help of her teacher she could also do morning exercises.[4]

Lena G. joined us at the age of almost two. Her diagnosis read: congenital deaf-mutism, congenital cataract in both eyes. At the age of three and a half the right eye was operated on and partial sight restored; the degree of vision could not be ascertained, however. Hearing loss was 80-85 decibels.

In the first few weeks at the home for deaf-blind children Lena was broken of the habit of being constantly carried around by adults. It took almost four months to toilet-train her. During her first year Lena learnt to find her way about within a familiar setting, and mastered the basic self-care skills: eating with a spoon, drinking from a cup, dressing and undressing. At the end of her second year Lena could find her way about easily within the rooms of the home and in the garden.

She had also learnt by then to look after herself in all respects: to undress and dress herself, to hang up her clothes tidily (she had also learnt to differentiate among her various garments and to put them away). She had learnt to eat independently, to use a napkin, to wash herself with soap, to dry herself with a towel and to use the toilet.

She enjoyed being taught how to use various toys and other learning materials, she took part in such work with obvious interest. Gradually she became more painstaking at lessons. She learnt to take apart and assemble sorting pyramids; to distinguish between toys of various shapes (cubes and balls) and group them together accordingly; to play with dolls (wrap them up, put them to bed, feed them and push them around in a pram or toy car); to enjoy ball games – to roll balls from wherever she might be sitting to the wall, to throw a ball to her teacher; to knead and roll out plasticine; to tear and fold in half pieces of paper; to play with simple puzzles (placing shapes in their appropriate holes); to climb up wall ribs, jump from a chair to the floor, crawl under a rope, and to perform simple physical exercises.

She also enjoyed action games such as “Catch me!” and “Train.” In addition to these action games and exercises much time and attention were devoted to developing the child’s means of communication: she was given her first instruction in sign language. By the end of the second year Lena had mastered about thirty signs, denoting regular activities in her daily routine, skills of self-care, and individual toys. She made active use of these in her communication with people around her.

In learning games such as “Dressing Dolly,” “Putting Dolly to Bed,” and “Feeding Dolly” Lena’s new skills and signs to denote them were consolidated.

At the very end of her second year she started to show an interest in dactylic speech. She “inspected” the hands of other pupils and adults, when they were conversing using finger-spelling. Sometimes she would try to make a finger movement similar to one she had “observed” into the palm[5] of another child. Lena realised that moving fingers over the palm of another person constituted “conversation.” First attempts were then made to show her the initial letters of her teachers’ names and those of her favourite toys (doll, ball).

By the end of the second year Lena was able to fingerspell the initial letters of her teachers’ names and of the words ball and doll.

In the third year of the preparatory stage Lena learnt additional skills of self-care and refined those already acquired: she learnt to straighten out and tuck in her bedclothes, to brush her teeth, to distinguish between her right and left shoes as she got dressed and also between the back and front of a pair of tights, to tie up her shoe laces and to help teachers dress the younger children.

Specially organised opportunities for Lena and her fellow pupils to “observe” adults in the home going about their work, animal life (rabbits), changes in the weather and to undertake household tasks within their grasp (helping wash dolls’ clothes, dusting the furniture in the room shared by the three girls, helping to change bed linen on bath-days) encouraged her to take a greater interest in the life around her and to extend her sign vocabulary.

Lena learnt new signs quickly and made active use of them in her communication with others.

Towards the end of her third year at the home Lena had learnt close on ninety signs, that denoted not only activities in the daily routine, skills that the routine required of her, but also various natural phenomena (snow, rain), expressions of emotion (crying, laughing, anger). She learnt how to convey to other people through signs, both requests and accounts of what she had seen and experienced.

In the course of her learning games Lena learnt to differentiate various sets of objects by shape and size. By feeling them over she could pick out a single object from a whole group of others.

In classification games involving toy articles she learnt to put articles away according to their designation (linen in the linen cupboard, crockery in the sideboard, etc.). She learnt to construct objects out of wooden rods and cubes from models or from memory, or by imitating the actions of her teacher.

She learnt to roll out plasticine into long sausages, to join the ends of these together to make rings, to mould plasticine using circular movements to make balls and then to make indentations in the latter (producing apple shapes, for instance).

The range of action games, in which she could take part, also grew and she learnt to cope with more complex rules and to respond to the signals given her by her teacher.

She could climb well and nimbly through a hoop, under a rope, step or jump over various obstacles, jump up and down on the spot on either one or two legs.

In the second half of Lena’s third year the teachers began to replace certain signs with dactylic words, and give instructions to the girl partly in dactylic words and partly in signs (for the phrase go walk she would use a finger word and a sign; for the phrase give ball she would use a sign and a finger word).

By the end of the third year Lena could spell out the whole of her name in dactylic letters, also the names of the other girls in her group, those of her teachers and moreover the words doll, ball, tea, give, soup. She understood and responded to instructions conveyed to her in finger-spelling (go for a walk, come and eat, give ball, give doll).

Lena often asked of her own accord if someone would show her in manual letters the name of this or that article.

During the summer holidays Lena was at home with her family and no one worked with the girl which resulted in her forgetting almost all these manual words. However, her interest in the work continued unabated. During the next academic year she continued to work at her finger-spelling with a lively interest. She quickly re-learnt the dactylic words which she had known before.

She mastered new dactylic words as well, and learnt to spell them out independently (pudding, soup, tea, milk, bread, coffee, walk, go, give chair). Some of her requests she also learnt to express in dactylic letters: give ball, give doll, give chair, give soap.[6]

Elena B. came to the home at the age of four. Her condition was diagnosed as follows: after-effects of a birth trauma (interruption of cerebral circulation); deaf-mutism, congenital cataract in both eyes, a convergent squint. Hearing loss in the speech range of frequencies of 70-75 decibels. At the age of eleven months Elena underwent an operation on her right eye which was successful, and partial sight was restored. The left eye was operated on when Elena was aged two and a half. The second operation was not a success and, according to the mother, it was after that that the squint appeared and the girl’s sight deteriorated. It was not possible to check the degree of vision, but the residual sight still possessed by the girl helps her find her way about, and at a distance of between ten and twenty centimetres from her face to distinguish objects and gestures. Before the age of two the mother had already started to teach Elena skills of self-care. At the age of three the child was sent to an ordinary kindergarten. The teachers at the kindergarten used to give Elena individual sessions and continued to develop self-care skills. They taught her to follow a regular timetable, to eat by herself, to use a pot, to wash her hands, to help an adult when he or she was undressing or dressing a younger child. Efforts were made to involve the little girl in group communal work. While performing her monitorial duties Elena laid the table putting out spoons, plates and bread and later after the meal cleared the tables.

In the kindergarten Elena was taught to play: to wrap up a doll in a blanket, rock it to sleep, make the doll’s bed. When the little girl came home from the kindergarten in the evening her mother tried to involve her in her own household chores. If the mother was doing the washing, she would set up a small chair nearby for her daughter, pour some warm water into a bowl and let Elena wash her doll’s clothes, which she would then hang up on a washing line using clothes pegs.

For her communication with her mother and the other children in the kindergarten Elena invented certain signs. When she wanted to eat, she would point a finger into her open mouth. She conveyed the idea drink by moving her lower jaw up and down. If Elena pulled her pants down that showed she wanted to go to the lavatory. Washing hands, face or hair she would convey by hand movements representing these procedures; the idea of going she conveyed by swinging her hands backwards and forwards as she would do when walking along, the idea of going somewhere she conveyed by waving her hand in the required direction, that of sitting by patting the seat of a chair or settee with her hand.

After spending a year in this ordinary kindergarten Elena joined our school. Elena found no difficulty in adapting to our household routine. She quickly learned to find her way about her room, the floor and later the whole building and the garden.

Work then began on refining those skills of self-care she already possessed and developing her capacity for play, and she started special exercises for promoting her sensorimotor development and extending her means of communication.

By the beginning of her second year in the home Elena’s self-care skills had perfected considerably as had her behaviour patterns. At meal times she sat properly at table, used a spoon, knife, fork and napkin, ate cleanly, and at the end of a meal would make a sign to say “Thank you” without needing to be reminded. Elena had learnt to brush her teeth, use the toilet Properly, dress and undress herself quickly (without putting her tights, pants or vest on back to front), and tell her left shoe from her right.

The main objective in teaching work with Elena at that time was to develop the range of her means of communication. The one-word signs (such as eat, drink, wash) which she had mastered before coming to the home, were not enough to enable her to communicate with other people. All the objects connected with the actions the girl carried out in self-care procedures and in her daily routine, the toys, actions required in games she now learnt to denote with new signs. In her first few weeks Elena learnt to understand most of these signs. The next step was for the teacher to guide Elena’s hands to reproduce the signs, and then Elena began to repeat some of them independently, and soon started using them to communicate with others. After spending a mere two months in the home Elena had learnt more than thirty signs. By the end of the first academic year the little girl’s vocabulary consisted of ninety signs and included not merely individual words but also sign sentences. Elena could also use signs to convey short accounts of events in which she had played a part. In the middle of her first year Elena could follow instructions for learning tasks designed to build up her verbal dactylic speech. Certain actions and familiar objects were referred to by the initial letters of the words denoting them. After Elena had been given frequent opportunities to observe manual conversations between older pupils she started to imitate the “conversations”: she tried to make small movements with her fingers on the palms of the other children. Gradually certain signs came to be replaced with dactylic words. By the end of the first year of instruction Elena could independently finger-spell her own name and also the name of her teacher and several other words, such as tea and give (these involve the same vowel sound in Russian – chai, dai). She understood the dactylic words for pudding, soup, tea, ball, water, chair, table, doll (all consisting of either one or two syllables in Russian. – Trans.). Elena was also competent at joining in such games as “Mothers and Daughters,” “Nurses and Doctors,” “Hairdressers.”

Work programmes to foster the development of such children are aimed at refining existing skills of self-care, inculcating habits of polite and clean behaviour, at educating through work (such as tidying the play corner, dusting, participation in group work to tidy up the room), at developing play activities (through games such as “Who Is Absent? “, “Dolly’s Bath,” “Shops”); the children are also taught to model in plasticine and to work with paper (cutting and gluing). They do physical exercises to improve their walking, running, jumping and climbing skills, and take part in action games such as hide-and-seek, rolling a ball through a hoop and racing over a specific distance to a known target such as a flag.

Children’s means of communication are developed both as they go about seeing to their own daily needs, in games, at walks and as they are being taught manual work skills. In addition special study sessions are provided during which the children carry out commands from their teacher transmitted to them in finger-spelling: Give chair, Give doll, etc. Dactylic words are also used to describe actions that have been performed or have taken place: “Doll fell,” “Lena sat.” The children are also taught to name objects such as their garments, parts of the body, household articles, pieces of furniture, things outside in the garden or street.

During the school period deaf-blind pupils master verbal language, study the subjects of the general curriculum, and acquire the work skills in one or another of the home’s workshops.

At this stage instruction is based on the materials and teaching programmes for speech development, object lessons, mathematics, practical work sessions and physical training elaborated at the Institute.

Materials in these teaching programmes are designed for children who have completed the preparatory stage in the home for deaf-blind children or at home. The programme covers a nine-year period, during which it is anticipated that pupils will come to master verbal language, cover the general knowledge programme of an ordinary primary school and develop the necessary physical and work skills enabling them to make the subsequent transition to an apprenticeship in one of the trades open to them.

Study sessions for these children take place not only in the morning but also in the afternoon after the children’s daily walk and in the evening. Many of the lessons, particularly object lessons, are conducted in the form of excursions and outings.

There now follows a short resume of the basic materials used in speech development, arithmetic and object lessons.

Mastering means of communication is a vital factor in the tuition of a deaf-blind child. Signs are the first special means of communication he learns. He uses them to denote objects, their functions, actions and elements of behaviour. Learning to use signs is a vital step in the child’s speech development.

The next stage in teaching a deaf-blind child to communicate is developing verbal speech. Word speech in its manual form is the superstructure built up on the basis of sign-speech; it takes shape and emerges within sign-speech as a variant of the latter, and then proceeds to develop as an independent dominant speech form.

This development proceeds as follows. Signs denoting familiar objects encountered frequently in the course of the daily routine are gradually replaced by words in finger spelling. For the child these designations are also signs, merely signs with a different configuration. It is indicated to him through a sign that a given object can be denoted in another way. Later he denotes the object shown to him with what is for him a new sign, without even suspecting that he already masters a word consisting of letters, just as a child with normal sight and hearing, on learning to speak in his third year of life, does not know that he is using words made up of letters.

Learning verbal language starts not with letters but with words, and not simply with words as such but with words as part of connected meaningful text. The sense context for the child’s first words are signs. The child’s first dactylic words are incorporated into a story that is transmitted by means of mime. Only after a child has mastered several dozen words denoting concrete objects can it come to grips with the dactylic alphabet, which in practical terms it has already learnt. Once it has mastered finger-spelling it can be taught any word, provided the correlation between the object and the corresponding sign is made clear.

Learning by heart the letters of the dactylic alphabet is a tremendously important step forward, because in so doing the child is learning to perceive dactylic letters conveyed by the hand of his teacher.

After learning the dactylic alphabet by heart, the child is acquainted with Braille signs for the letters. Each Braille letter is associated in the child’s mind with the manual designation of that letter, with which he is already familiar.

The child needs to achieve a perfect manual “articulation” and get a faultless grasp of Braille letters made up of dots. To work towards this end a special vocabulary of two or three dozen words is selected, words denoting objects with which the child is familiar. This vocabulary is subsequently used as a means to mastering the most important feature of verbal language – namely, grammatical structures.

It is important to note here that the child masters grammatical structures through his practical language work; he does not make a study of grammar as such. It is in a similar way that a child with normal sight and hearing comes to master speech, for at the age of two or three he uses language correctly but naturally has no knowledge of grammar.

In order that the child master the grammatical structures of word language the written word must be exploited – namely reading and writing. At first the teacher teaches the pupil to read and write texts consisting of simple non-expanded sentences describing actions involving objects. Then the texts are made more complex by the introduction of simple expanded sentences. Words and word-groups, all grammatical categories in logical connected text describing an event familiar to the child, are mastered by him as they are absorbed into his system of image-and-action reflection of the particular event concerned. In the course of this process it is essential that each new word and each new grammatical category is complemented by an immediate image of the concept designated by the word or grammatical category in question.

To promote faultless mastery of language a system of parallel texts has been evolved: texts presented to the pupils by their teacher in the course of their class-work and “spontaneous” texts composed by the pupils on their own.

New words and grammatical categories are gradually introduced into the class texts presented to pupils by the teacher. When composing his own text describing an event familiar to him the pupil makes use of the new forms provided earlier in the class text and consolidates his knowledge of them by using them in his own material.

Reading is a vitally important factor in deaf-blind children’s instruction. The gradual initiation of a child into the art of reading Braille literature, the imparting of a love for books and fostering the habit of reading both fiction and popular science books are all conditions for his subsequent attainment of a high level of development in the process of self-education, and “the sky’s the limit.”

While pupils are working towards this mastery of elements of narrative speech, work is also in progress to develop their conversational speech (in dactylic form), first as hortatory sentences and later more complex ones.

The low level of a child’s initial mastery of verbal speech must not be allowed to limit his communication, because that in its turn would inevitably hold back his overall development. It is essential, particularly in the early period of his tuition, that communication via signs be extensively used.

Oral (vocal) speech is riot a medium of teaching for deaf-blind children, it is a subject of study for them. Work at vocalisation is conducted at individual lessons. The level of a pupil’s articulatory skills should not constitute an obstacle impeding his mastery of verbal language.

In the teaching of deaf-blind children object lessons constitute one of the main methods for transmitting to them knowledge about the world around them. Objects are studied in a specially designed sequence, the correlations and interrelations within which must be comprehensible to the child. At object lessons, which coincide with lessons for speech development, pupils come to master new phenomena of language and develop their skills in verbal communication.

Knowledge acquired during object lessons is then consolidated through reading and working at class texts. Pupils write compositions on their own which are then corrected and amplified by their teacher. Class texts are either compiled by the teacher or selected from readers and presented to pupils in a form accessible to them. These class texts are compiled in such a way as to encourage the pupil’s logical thinking, to help him express his thoughts, to enrich his speech and to consolidate the knowledge he has obtained at object lessons. When pupils are called upon to read class texts and write compositions, they are acquiring first-hand knowledge of natural phenomena, typical for the current season, of work-tools and man’s work in agriculture and industry, of all manner of things connected with man’s life and activity of the world of animals and inorganic nature.

The subjects of the pupils’ reading and compositions are determined by the subjects covered in their object lessons, after which pupils go on to consolidate new knowledge in the form of stories accessible at their level.

In the seventh year of their schooling pupils embark upon a systematic course in nature study; they are also given elementary information in geography and in the history of the Soviet Union.

In the years of schooling that follow it is the teacher’s objective to systematise and extend the pupils’ knowledge of nature, to acquaint them with the ways in which man utilises nature, to teach them how to use a map, and to instil in them love and respect for their native land and the desire to take part in socially useful labour.

The curricula for the seventh, eighth and ninth year of schooling provides pupils with a grounding in general knowledge and lays the foundation for their subsequent study of biology, geography, and zoology; it also helps them to understand nature around them, the work performed by their fellow human beings and the world of animals.

The teaching of mathematics to these children is designed to enable them to carry out mathematical operations involving whole numbers and fractions, and then to use this knowledge to solve mathematical problems and carry out simple calculations in practice.

The extent of mathematical information given deaf-blind pupils during their nine years’ schooling corresponds in the main to the material covered in the first four classes of the normal school syllabus (for pupils aged between seven and eleven). However, the order in which the constituent elements of this syllabus are presented to the pupils differs from that used in ordinary schools. The syllabus used for deaf-blind children in the main follows a linear progression: in other words after starting work on a particular topic (such as numeration) pupils follow it right through to the end within the framework of the given syllabus. Then they switch to the next topic which is also followed through to the end. Teachers at our school had to abandon the concentric method for the presentation of mathematical material (when this method is used mathematical operations are studied first within the limits of certain sphere and then extended in broader limits). The linear method proved far more economical at our school in terms of time and helped pupils form a far more complete picture of each topic.

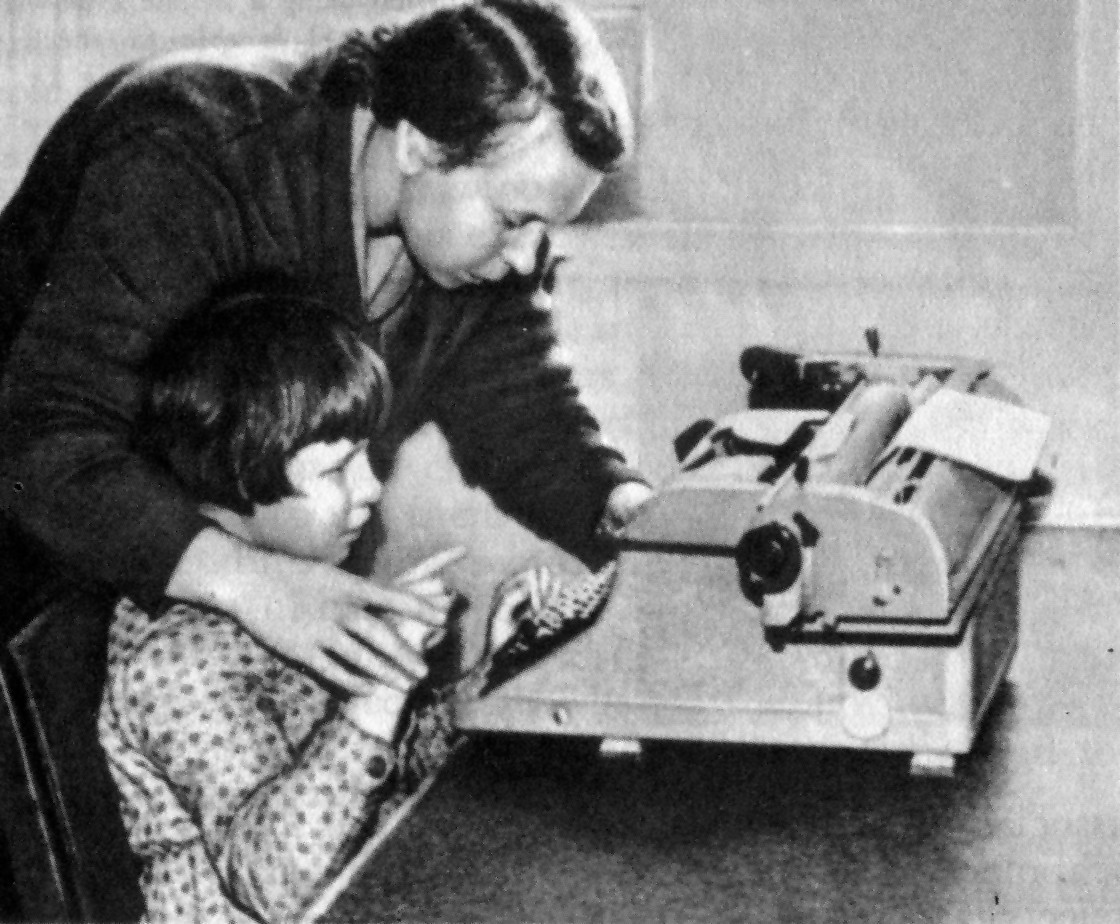

In their first year of schooling the study of mathematics starts out from learning numbers up to a thousand, which enables the pupil to grasp the basic idea of the decimal system. The children are taught to master numeration with the help of counting sticks and other aids. The ordinary abacus also proves a most useful and convenient teaching aid.

Once pupils have a firm grasp of numeration then they move on to the four basic rules of number in the following order: addition, subtraction, multiplication and division.

Pupils are also given materials for the study. of measures. While they are working on concepts of measurement, great importance is attached to practical tasks connected with measurement, weighing and the calculation of distance. Particular attention is paid to teaching pupils units of time and how to tell the time with watches (complete with raised figures).

When being taught to solve mathematical problems, the children start out from practical activities with objects. Gradually these problems become more complex and their solution has less and less to do with concrete actions.

First Year

The deaf-blind pupil will be taught verbal communication using the dactylic alphabet; he will master reading and writing using the Braille script. The speech-development syllabus in this year includes teaching children to name (using finger-spelling) objects from his familiar environment, and to understand and carry out simple commands, formulated in words (stand up, go, take, etc.). The pupils learn to denote their actions using simple sentences consisting of words (e.g., I played, I’m writing ... ), to describe the actions of others (Olya’s eating. The doll’s lying.), and to answer simple questions (What’s your name? What were you doing? What did you eat?).

In the course of object lessons the child is made familiar with the home as a whole: the classroom (floor, walls, window, door, radiator, furniture, teaching aids, typewriter, abacus, etc.), the dining room (crockery, furniture), food (soup, pudding, bread, etc.), the bedroom (bed, bedside locker, wardrobe, bed linen), the bathroom (basin, tap, soap, etc.), the cloak-room (hanger, cupboards, shelves where shoes are put to dry).

At a level within the children’s grasp they also study “Clothes” (dress, shirt, trousers, coat, etc.) and “Footwear” (slippers, indoor shoes, walking shoes, felt boots).

The children acquaint themselves with the shape of each thing, learn what it is for, then learn its name and how to denote its function. They also study such topics as “Fruit” and “Vegetables” associated with their meals. While they are being taught clean habits they learn names for the parts of the human body: head (face, cheek, nose, mouth, hair), arms, legs, trunk.

Looking after the animals in Pets’ Corner, they learn the names of animals and birds. When working on the school allotment they make a study of plants, bushes and trees. The children learn to mould out of plasticine the objects they are studying and to recognise models and plaster casts of them.

In lessons the pupils are taught numbers up to a thousand, the signs denoting these numbers and the Braille symbols for them. They are taught to count forwards and backwards. They are introduced to the abacus. In their work on the calendar they master the concepts yesterday today, tomorrow. They also learn to recognise and model spheres, cubes and rods.

Second Year

The speech-development syllabus for this form is designed to promote the understanding of more complex instructions expressed in words (Sit at desk. Repeat. Give some examples. Take book. Put exercise book on table). The pupil learns to express his requests in words (Give me exercise book please. May I go out? etc.), to give both short and extended answers to questions (Have you written it down? – Yes, I have written it down, etc.) and to ask questions (Who’s come? What’s your name? ).

Pupils learn to put together a narrative describing a number of interrelated actions (Olya sat down. Olya took Plasticine. Olya modelled house. Olya washed hands).

In their object lessons pupils’ knowledge is consolidated and extended via excursions, visits to the Pets’ Corner, and work on the school allotment. The topics studied in the object lessons are partially repeated, but at the same time the children’s vocabularies are extended. At the home the children are introduced to the library, the doctor’s consulting room, the staff room, and in the dining room children investigate crockery and various appliances. When pupils visit the homes of their teachers, they are introduced to the latters’ family (father, mother, children), these people’s professions (driver, doctor, road-sweeper, stoker, technician), with features of the town (blocks of flats, roads, pavements), with transport, household pets and study the topics “Garden,” “Allotment,” “Wood,” “Meadow,” “River.” They are taught the names of the seasons and various kinds of weather (winter, summer, autumn, spring, snow, rain) and join in the celebrations for various public holidays.

In their mathematics lessons they are taught addition involving up to three figures (without having to carry). They learn the concepts week, month (as they make dated notes in their exercise books). They learn the ideas of a circle, square, triangle, rectangle.

At the end of the second year pupils are taught to solve adding sums and add a small number of units to a number.

Third Year

The speech-development syllabus for this year requires that pupils learn to carry on conversations using dactylic words on certain themes which they sustain for several sentences: “Where are you going? – To the doctor – Why? My foot hurts. I was out sledging and fell.” Pupils learn to express in a narrative sequence the events of their day (“How I Spent Sunday”) and they learn to write letters.

In their object lessons they continue their study of the home (kitchen, boiler room, shower-room) and in the dining room they study food, crockery, furniture. They familiarise themselves and learn the names for various types of clothing, footwear, headwear. They make a broader and more detailed study of the concepts family (brothers, sisters, grandchildren, etc.) and profession (hairdresser, postman, tailor, etc.)

During their outings to the country the pupils are acquainted with the work of the farmers, inspect the livestock and agricultural machines. They cover such topics as “Insects,” “Fishes,” “Animals” (tame and wild), “Vegetables,” “Fruit,” “Indoor Plants,” “Woods.” They continue to study the changing seasons and celebrate the public holidays of the Soviet people.

In mathematics they study addition involving carrying with units and tens and addition with three figure numbers without carrying. They are introduced to the shapes of the figures used by sighted people, to coins, the various notes of paper money, and measures such as litre and half-litre. The children are taught to do adding sums involving one or two operations.

Fourth Year

The speech-development syllabus for pupils of the fourth year provides for teaching pupils to carry on question-answer type conversations independently, and to answer questions with a short narrative (“Where have you been? – I went to the shop. Nina Ivanovna gave me money. I bought a book”), and they are taught to write letters to their parents, friends and teachers. The pupils also learn to describe events from their personal experience in a sustained narrative.

In object lessons they continue their investigation of the home (taking in the various floors, the cellar and the attic), gradually building up a picture of the house as a whole and extending their knowledge of the function of all the premises, and of the work that goes on in them. Special excursions enable them to learn about various types of shops (a dairy, grocery shop, the baker’s). Pupils are taught to classify various objects in groups: food (raw, cooked, liquid, solid), footwear (leather, rubber), etc. Their concept of the family is extended to include such members as sisters, grandmothers, uncles. They learn to identify the seasons and months of the year and learn about the woods in more detail (mushrooms, berries, etc.), also the near-by allotment (edible plants and weeds) and they start to keep a nature calendar.

In mathematics they learn to do subtraction sums involving numbers up to a thousand and to solve problems using subtraction.

Fifth Year

In the fifth year the speech-development syllabus is designed to teach pupils to give a detailed account of an errand they have performed (I went to the kitchen. I asked the cook for beetroot. I brought the beetroot to the classroom.), to describe in words (dactylic and in Braille) an event or series of events picking out essential details, and to expound something he or she has read in answer to questions from the teacher.

In object lessons pupils keep their own nature calendars.

At the end of each month they compare their calendars with the corresponding ones from the previous year. In their Pets’ Corner they learn to look after animals: rabbits and fish in the aquarium. They grow plants from seeds, bulbs or cuttings, first in seed boxes and later in beds.

As the pupils look after indoor plants and later beds in the allotment, the teacher develops their work habits and extends their knowledge of plants and potential skills for this work. They also extend their knowledge on other topics: “Garden,” “Woods,” “Animals,” “Seasons” (early and late spring, autumn, winter, summer).

Pupils read appropriate passages from the reader for Form Two of the ordinary school. (In the school for the deaf-blind some text-books designed for ordinary schools are used, only they are printed in Braille script.) The teachers provide commentaries to these texts, and teaching aids are also used.

In mathematics the pupils study linear measures, multiplication, units of time (days, hours, minutes, seconds) and learn to do simple multiplication sums.

Sixth Year

According to the speech-development syllabus of the sixth year, pupils are taught how to describe in words (through “conversation” or in written compositions) various objects with which they are familiar (the school, an animal or plant). They start keeping a regular diary. They describe outings and the life in their home. They write précis of reader stories on the basis of plans drawn up in advance.

During their object lessons they study the weather of the various seasons, the link between the weather and various types of labour. They make a comparative study of town and country, life (what people do there). They are acquainted with social institutions: health centres, chemist shops, post offices, railway stations, harbours, aerodromes, etc. They extend their knowledge of wild and tame animals, of the garden, vegetable allotment and near-by woods. They learn about the surrounding countryside outside their town (meadows, fields, copses, orchards), they learn how to find their way about in open fields, and form an idea of different kinds of land surface (plains, hills, gullies). They model the relief of their locality in plasticine. Pupils also read the relevant chapters in the standard readers for ordinary schools (Books Two and Three).

In mathematics lessons they now tackle division. They are introduced to weights, and start using scales, and doing division sums.

Seventh Year

The speech-development syllabus for this year requires of the children that they learn to describe an object (such as a room or an animal) in comparative terms, provide detailed accounts of excursions picking out the salient points of their experience, keep a diary with regular entries on specific topics, such as the weather or their work, write a précis of material they have read (with or without a plan made out in advance), carry on conversations on a variety of subjects and at different levels depending upon whether they are talking to an adult or another child.

During their object lessons the children work on such topics as “Weather and the Harvest,” “Climate,” “Nature and the Changing Seasons.” Throughout the year a detailed nature calendar is kept, and comparisons between current entries and those of previous years are made from which conclusions are drawn. The children study the points of the compass (using special compasses for the blind), learn to understand and distinguish North, South, East and West, make plans of their room, or house in relief, and later relief models of the surrounding countryside. They start to grasp the concept of scale.

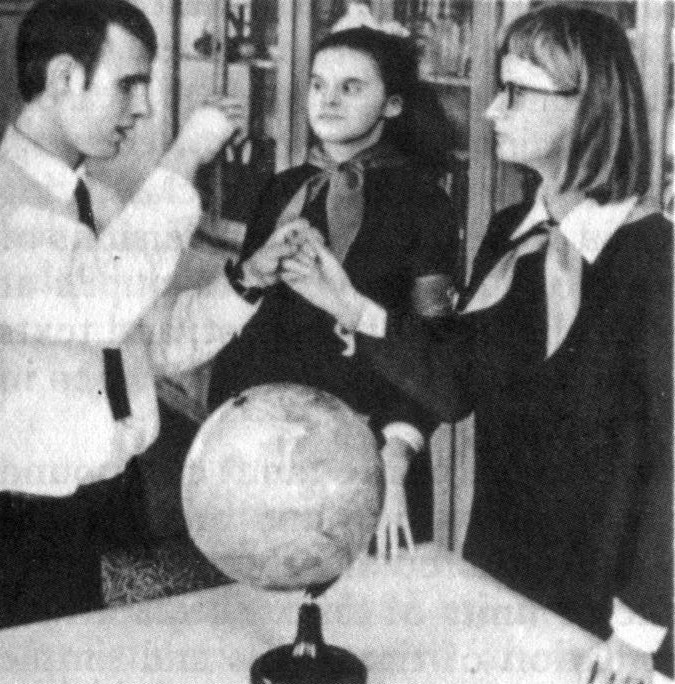

Pupils are introduced to relief maps of larger areas and countries, and a globe as a model of the earth.

As the pupils study the important dates in their countries calendar this work is supplemented by. reading the relevant passages from readers used in primary classes of ordinary schools (for pupils aged between eight and ten).

In mathematics pupils begin to study simple fractions and numbers consisting of several figures. Pupils carry out sums in the four rules of number using numbers up to a million, including problems involving parts of a whole. In geometry lessons the children are introduced to the concepts straight line, section: they learn to build squares and rectangles with sides of a specified length.

Eighth Year

In the eighth year the speech-development syllabus requires of the children the ability to work out a number of alternative answers to one and the same question, to describe an excursion in a composition written according to an independently devised plan, to write a précis of a story they have read, to write an essay on a subject of their own choice or one set by the teacher.

During object lessons pupils work on such topics as “Characteristic Features of Summer, Autumn, Winter and Spring,” “Flowers,” “Vegetables,” “Weeds,” “Useful and Harmful Animals,” “Plants Growing in Woods and Gardens.”

Practical tasks are carried out: pupils make starch from potatoes, plant out seedlings, gather in the garden crops. Pupils are introduced to the concepts: year, month, season, twenty-four-hour period, morning, afternoon, evening, night. They are taught to draw diagrams for classifying animals and plants. They read abridged, adapted versions of texts from the reader designed for ten-year-old pupils at ordinary schools that treat of their country’s past; and texts that tell of explorers and other famous men and women in the reader for nine-year-old pupils.

In mathematics pupils study prime and compound concrete numbers, reduction, conversion and arithmetical operations involving compound concrete numbers.

Pupils also study a table of units of time. They learn to solve problems in the calculation of time units and simple problems involving speed, time and movement.

The Ninth Year

The speech-development syllabus for pupils in the ninth year provides for their tuition in free communication with the people around them in verbal language; in reading simple fiction and popular science books, writing compositions which depict events both in their own lives and in those of others’, writing compositions on set subjects (such as bird life, winter, etc.).

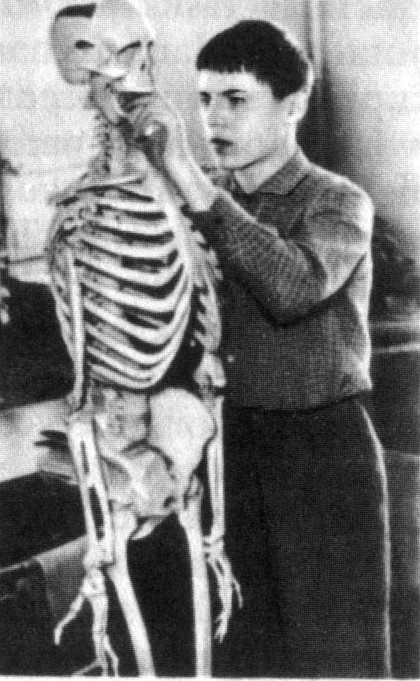

The object lesson syllabus continues nature study, study of the human body and personal hygiene. Information about the work carried out by various groups of people living in the Soviet Union, as well as more detailed information regarding the present and past of their native land is given. Topics such as “The Surface of Land,” “Minerals,” “Water in Nature,” “Air,” etc. are studied. When working on the topic “The Human Body and Keeping It Healthy” pupils study the skeleton, muscles, internal organs, feeding, diet, physical training, and they are also given some information regarding disease. In their practical sessions for this topic they are taught to feel a pulse, to count the pulse rate, to point out on their own body and those of other pupils the position of the heart and other major internal organs, to bandage cuts and wounds and to administer first aid for burns, frost-bite, etc.

Pupils are taught about the past and present of their country with the help of texts from the Form Four reader used in ordinary schools (pupils aged ten).

In their mathematics lessons these pupils learn Roman numerals, and how to measure area: they are introduced to the table of square measures, and to the measurement of volume. They learn to solve simple problems involving the calculation of area and volume.

The volume of knowledge covered in the syllabuses drawn up for our deaf-blind pupils, and the order in which topics are introduced are in no way binding for every pupil. The material outlined above provides initial guide-lines, which the teacher can refer to as he compiles a learning programme for each of his pupils that will take into account the latter’s individual characteristics. The allocation of various materials to specific years of the schooling programme should also be regarded as approximate and should in no way inhibit the teacher’s initiative. Some pupils will succeed in mastering the material outlined much more quickly than is suggested in the programme, while others, suffering from additional handicaps, will require more time than that stipulated.

It should also be borne in mind that some of the pupils will overtake the others in their class, while others will fall behind. Sometimes this makes it necessary to transfer a pupil from one group to another in the course of the school year.

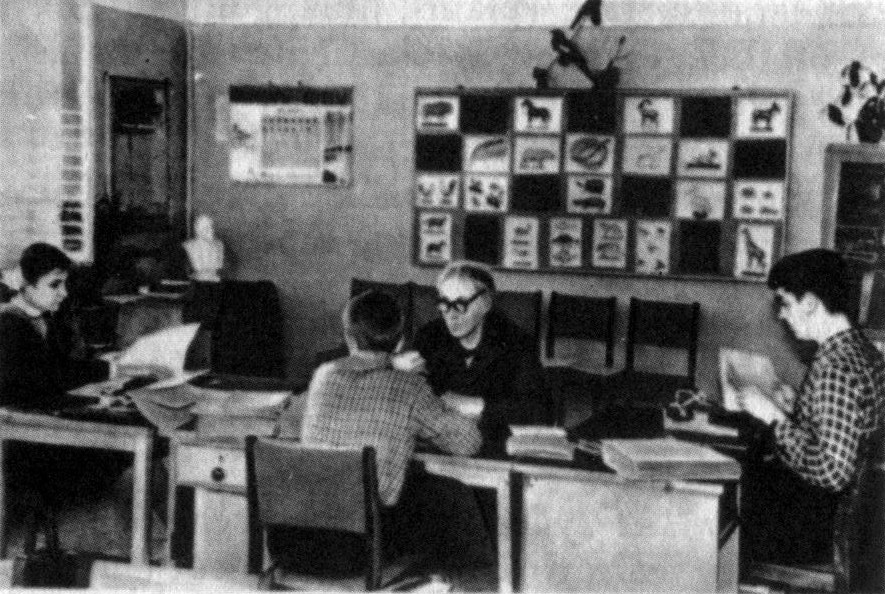

For schooling purposes groups of three pupils are selected: for the most part these three will work through the syllabus of one and the same year and possess a similar level of development. This makes it possible to use the technical equipment available at the home (various types of teletactor) at the lessons. However, it is sometimes advisable to group together pupils of varying degrees of development, when relationships between the latter shape in such a way that one serves as a model for another pupil and helps the latter. In both cases each pupil is taught according to an individual plan and at the optimal rate for his abilities.

Pupils’ capacities for assimilating a certain body of knowledge and the rate at which this can be done are determined by the individual characteristics of the pupils, which in turn depend upon the nature of the illness which impaired their sight and hearing in the first place, on the vestiges of sight and hearing perhaps still in their possession, on the conditions of life a child knew before coming to the home for the deaf-blind for tuition and the level of development he or she had attained in those early conditions.

In accordance with the methods used to teach them reading and writing, that were, in their turn, determined by the state of their sight, pupils at this school stage were divided into two subsections (consisting of sixteen and eight pupils respectively). The pupils in the first group (sixteen) were taught to read and write with the help of Braille script. Pupils in the second sub-section (eight), who were able to take in lesson material relying on their residual sight, used special text-books for the partially sighted (printed in large letters) and were taught to write “as the sighted.”

The first group, using Braille script, included pupils who were completely blind in both eyes (Fanil S., Vitya K., and Volodya T.) likewise Tolya Ch., who retained some sensitivity to light, enough to enable him to distinguish light from darkness, Semyon B., with a negligible amount of residual sight enabling him to distinguish finger movements at a close distance from his face, and finally pupils with central vision of between 0.01 and 0.04, able to use their sight to help them find their way about (Yana K., Tanya S., Lida A., Anna P., Olya Sh., Galya R., Sanya Ch., Dmitry H., Tata P.) Nata Ch., whose vision after correction had an acuity of no more than 0.09 and who, at her ophthalmologist’s recommendation was being taught Braille script was also assigned to this group, as well as Alexei B., whose sight in his one remaining eye had an acuity of 0.07 and was deteriorating.

In the second group (in which reading and writing were being taught as to sighted pupils) were placed pupils with 0.1 vision (Zana S., Misha F., Seryozha B., Dima D.), as well as pupils whose vision after correction had improved to as much as 0.3 (Lyuda S., Shura Ch., Sasha K., Inna X).

A special approach was needed in the case of children suffering from after-effects of diseases of the central nervous system, manifest in mental deficiencies, asthenia, motor malfunctions. These pupils were Tata P., taught with Braille script, Inna A. and Dima D., who were taught as sighted children.

Further perusal of diagnostic data and a resume of the progress made in teaching these children is most relevant here.

Fanil S. only began his proper schooling at the age of fourteen. His condition was diagnosed as follows: meningitis at the age of twenty months after which there followed complete loss of sight, hearing and speech. Subatrophy of both eyes and total blindness. Deaf-mutism. No vestiges of hearing found.

According to the boy’s parents, the child had been born normal. He began to walk before he reached the age of one year and he had started to use individual words, before his illness struck. Up until the age of twenty months he had been a strong, healthy child. When he fell ill, his parents did not call in the doctor at once and the diagnosis of meningitis was only established two months afterwards, when the boy had already lost his sight and hearing. The boy then stopped uttering the words he had known before.

Until the age of fourteen Fanil had lived at home, where his parents had taught him self-care habits and had initiated him in various work skills. At the time when he came to the home for the deaf-blind Fanil understood individual instinctive signs, shown to him through his own hands. Yet he made no independent use of these same gestures. In one school year he succeeded in covering the syllabus for the whole of the preparatory course.

The boy was clean in his personal habits and knew the basic rules of polite behaviour. In the morning he used to make his own bed, do his exercises, take a strip-wash, brush his teeth, wash his feet at night, look after his clothes and put them away tidily, etc. He learnt to mould objects from plasticine, to put together. various models using the parts of his construction set and take part in socially useful work, such as tidying up the classroom or the garden. He learnt signs and began to use them in order to communicate with his teacher and his fellow pupils as well. He also learnt the dactylic names of certain objects and actions. He learnt to read and write a number of words in Braille script, words which designated objects with which he was really familiar. He learnt to count up to a hundred, using signs, and to designate these figures by raised dots.

During the second year of his schooling Fanil covered the syllabus for the first year of tuition in the school for the deaf-blind: he learnt to communicate via signs and some dactylic words; he learnt to describe certain actions and “events,” consisting of a number of actions using dactylic and written words, in Braille script; he began to write short compositions describing his life and to keep a diary. Work now started on teaching Fanil to vocalise certain words.

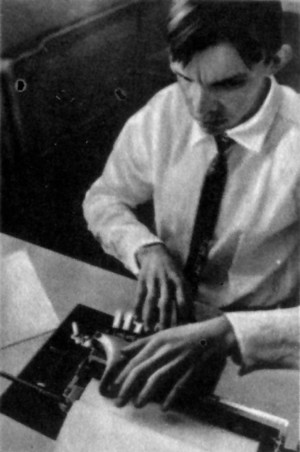

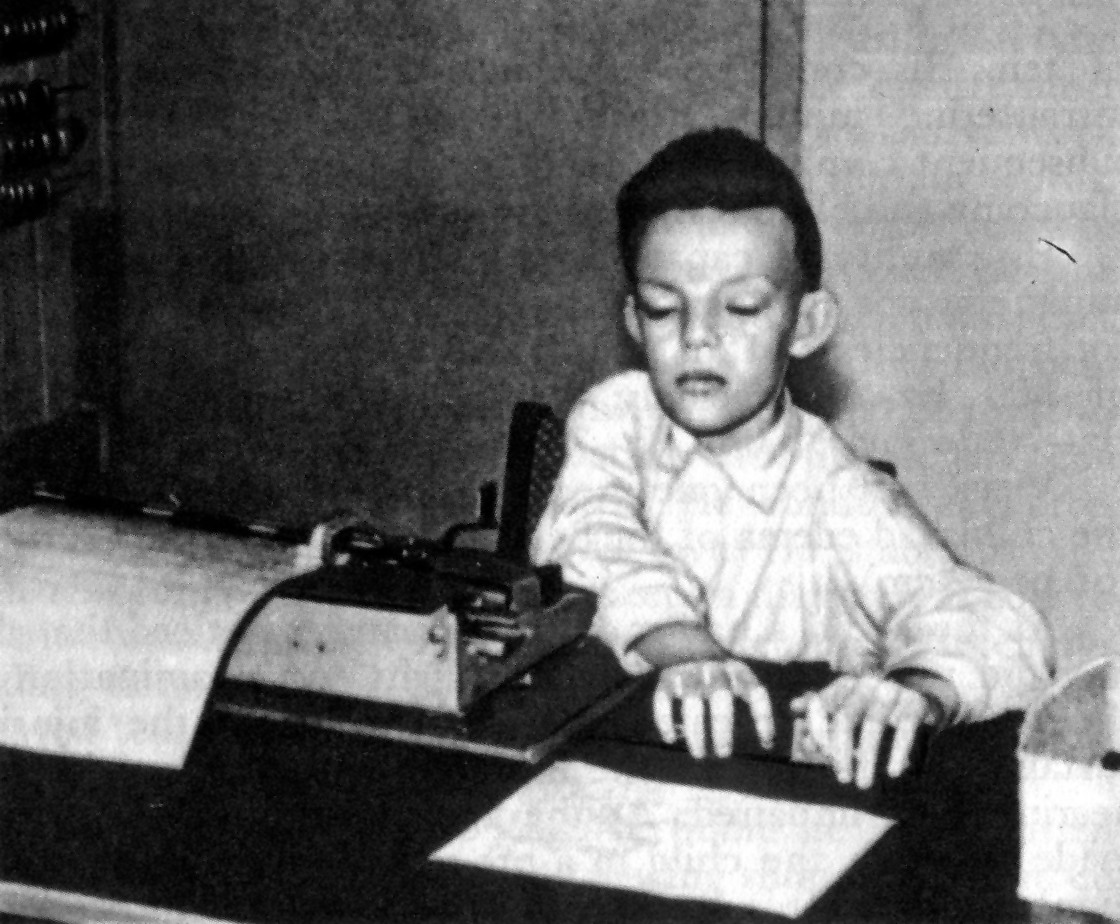

In his third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh years of schooling Fanil covered the syllabus envisaged by the programme for the deaf-blind. For communication purposes he uses finger-spelling and is able to ask questions independently and to provide correct answers to questions put to him by others. When communicating with people who can hear he vocalises ordinary words. He conducts a correspondence with his relatives on his own. He is able to type with an ordinary type-writer. He keeps a diary. He is able to describe excursions, in which he has taken part. He enjoys reading fiction (either stories written in simple language or adapted texts). He can solve simple sums and mathematical problems.

During his time at the Zagorsk home he has acquired work skills in the carpentry and sewing shops and learnt to use machine-tools for the production of safety-pins. He started working at a professional level (as a member of the association of blind workers) during the fourth year of his schooling. His output was of a high quality free from rejects. He received wages and sent money home to his parents.

Vitya K. came to the home for the deaf-blind at the age of ten. His condition was diagnosed as the outcome of intrauterine injury to the central nervous system and subsequent complications; cataract in both eyes, secondary glaucoma and blindness; deaf-mutism.

His auditory capacity was investigated using tonal audimetry and the loss of hearing established was as follows: for frequencies of 125, 250 Hz – 65 decibels; for frequencies of 500 Hz – 60 decibels; 1,000 Hz – 65 decibels; 2,000 Hz – 70 decibels; 3,000 Hz – 75 decibels.

Vitya had been one month overdue at birth. At birth the child had edema of the head and clefts in cranial sutures (of 1 to 2 cm).

At three and a half months the parents noticed that the boy did not react adequately to light. An examination at the local clinic revealed that as a result of the injuries sustained at birth and the late delivery Vitya’s sight and hearing were impaired. At the age of five an attempt was made to teach the child in a pre-school group of deaf and dumb children. It is not known what residual sight the child possessed at that time, but after spending three and a half months in a group the boy was removed in view of his weak sight. At six Vitya fell into a cellar and injured his head again: detachment of the retina resulted from this accident and he lost his sight completely. He had never been able to speak. Until the age of eight the boy remained at home where his parents taught him to eat, dress, wash and use the lavatory independently. He had learnt to use some signs. At the age of eight it was decided to place Vitya in a home for handicapped children where he was given no suitable instruction and began to lose the skills and knowledge of signs which he had acquired previously.

He entered the Zagorsk home for deaf-blind children when he still had a good grasp of certain simple signs and possessed a small active vocabulary of signs he used in communication. He had also trained in various skills of self-care.

His behaviour was very excitable, he cried a lot and threw tantrums. He also tired very quickly.

In the first year Vitya was taught habits of correct behaviour, communication through signs, the use of a certain number of manual words and covered the preparatory stage of the course in writing in Braille script.

In his second year Vitya began to work through the syllabus for school work. He managed to keep pace with this course from year to year. In his seventh year at the home Vitya worked through the syllabus for pupils in their sixth year at the school. He was able by that time to communicate with other people using finger-spelling; he understood questions asked of him, was able to answer them and ask questions independently; in manual words or in a written form (Braille script) he was able to describe an event he had witnessed, and he was carrying on a correspondence with his parents. He could use vocal speech as well, although it was badly articulated. He could read and understand class texts specially written for him or taken from the second or third year readers for ordinary schools.

Vitya could do sums and problems taken from mathematics text-books for second- and third-year pupils in ordinary schools. lie worked in the carpentry shop and learnt among other things to use a fret-saw, and he mastered the operations necessary to work machine-tools for the production of safety-pins.

Volodya T. was given individual tuition at the Institute for Research into Physical and Mental Handicaps and then at our home. He began his tuition at the age of seven. His diagnosis read: tuberculosis meningitis at the age of three years and eight months. At the age of one year and four months he had chicken-pox and infectious hepatitis. At the age of two he was discovered to be suffering from enlarged periauricular lymphatic nodes. His parents also noticed that the child had begun to lose his hearing. Before he fell ill with meningitis the boy had only uttered a few individual words such as: papa, mama, baba (granny). He lost his sight and hearing as a result of the tuberculosis meningitis. In the range of usual speech frequencies his hearing loss exceeded 75 decibels.

While still at home Volodya had been taught some self-care skills. When he joined the group of deaf-blind pupils receiving tuition at the Institute at the age of seven, Volodya’s physical development resembled that of a normal five-year-old. He could not tolerate to be on his own and his behaviour was excitable.

The first year at classes provided at the Institute was spent on reorganising his behavioural patterns, training him in the skills of self-care, acquainting the boy with objects around him and teaching him some signs.

During Volodya’s second and third year he was acquainted with his environment in accordance with the pre-school programme. He learnt to use sign-speech and started work on manual and Braille words. He would carry out the instructions of his teacher when these were transmitted in finger-spelling (hortatory speech), and he had learnt to read simple texts in Braille script: he could also count up to thirty.

In his fourth and fifth year of tuition Volodya continued to work at conversation in dactylic form. He started to grasp concepts of time (yesterday, today, tomorrow, week, and the days of the week) and grouping concepts (crockery, clothes, footwear). He began to write a diary, his first compositions and his first letters to his parents. It was also at this time that Volodya read through his first book, which had been specially written for him and consisted of stories describing events from the child’s own life.

Over the course of five years’ tuition Volodya covered the materials designed for the preparatory stage of the course and the first-year school syllabus. By the end of that period the main form of speech he used in communication was finger-spelling. The boy was not yet ready to embark upon the task of vocalising. His written language was well developed: he could describe correctly events that he had witnessed during the course of a walk, while at play or in class, and he was also writing a diary. As regards the standard of his written work, he had reached the level expected of pupils in the third year at the school for the deaf-blind.

For a number of reasons, the boy was taught individually without coming into contact with other pupils. This had an unfavourable effect upon the development of his personality, and also on his progress in certain skills and abilities. These shortcomings in his overall development came immediately to the fore when, in the sixth year of his tuition, he moved to the home for deaf-blind children, where he had to live and work in a group of pupils his own age. It turned out that he was not prepared for communication with other children; he was not able to communicate with them in series of questions and answers. After only communicating with adults prior to this move, he had grown used to carrying out all their demands. He started to obey all the commands of the children without a murmur as well, and the latter, on realising how naive he was, began making fun of him, ordering him to do quite ridiculous things such as to lie down on the floor, to crawl into a cupboard, etc. Volodya then came to fear other children and avoid them.

In the first months that he spent at the home Volodyla began to learn to work in the carpentry shop and learnt to cope with all the work operations required for the manufacture of safety-pins.

Yana K. came to the home for the deaf-blind at the age of six years and five months. Her condition was diagnosed as stemming from injury to the central nervous system resulting from birth trauma: cataract in both eyes, acuity of vision in both eyes no more than 0.01 and deaf-mutism. The loss of hearing in the range of speech frequencies was 85 decibels.

Between the ages of three and four the little girl had attended a kindergarten, where she had been cared for individually. Between five and six Yana had been at a home for children with impaired hearing, where she had also received individual instruction. By the time she came to us Yana had mastered the skills of self-care: she could eat properly, dress and undress herself, comb her hair, tie a bow in her hair-ribbon, put on her shoes properly and tie up the laces. At the home for the deaf Yana had learnt to carry out the duties of a monitor, laying the table, watering indoor plants, and dusting their leaves with a wet cloth. She had also learnt to “speak” to the other pupils by imitating their mime and sign language. At that stage she had possessed more residual sight than was the case when she came to the home for the deaf-blind. Using what remained of her sight Yana had learnt to read and write large letters. She had also learnt the dactylic alphabet. She had a dactylic vocabulary of ten words, most of which were the names of the people around her. For everything else she used signs. She had also learnt to play with dolls and other toys. With no trouble at all she adapted to the time-table at the home for the deaf-blind. She quickly learnt to find her way about the building and the garden. In a matter of days she had mastered those skills of self-care which she had not possessed hitherto. She learnt to brush her teeth, wash her feet before going to bed, prepare her bed for the night, make it in the morning and wash small articles of clothing.

The girl started learning to play games that were more complicated than those she had known previously. She quickly mastered the point of role-playing and willingly. took on leading parts.

Since Yana had well-developed sign language at her disposal, work on verbal language in her case began with substitution of words for signs. The state of her vision by this time made it imperative to teach her Braille script.

It took the little girl only four months to master the Braille alphabet. By the end of her first year of tuition Yana was able to read short texts in Braille. By the end of her second year at our school she had a vocabulary of two hundred words. She understood questions dealing with household and every-day matters and answered them correctly. Her spontaneous communication with other children and adults consisted of a mixture of signs and dactylic words. At the end of her first year sign language was the dominant form, it merely incorporated isolated dactylic words. During the next year the share of verbal speech increased; her communication through signs incorporated not merely individual words but groups of words and whole sentences.

As Yana’s ability to communicate in words grew, she began to describe objects, actions and events (using dactylic words and the Braille alphabet).

During her first year at the home Yana covered the bulk of the programme of the preparatory stage of her schooling. In the second and third year she covered the material for the first and second years of the deaf-blind’s school course. The next year she also successfully completed the syllabus for the third year of that programme. By this time Yana’s main means of communication was verbal speech using manual words.

She also learnt to vocalise all speech sounds. However, her oral speech at that time was still insufficiently distinct since her enunciatory skills were not yet automatic. She was able to read and understand texts describing events with which she was familiar and was able herself to describe in words (manual or Braille) an excursion she had been on, to write letters, keep a diary; she also learnt to count, do sums and simple problems.

Semyon B. came to the home for the deaf-blind from his own home at the age of eight years and nine months. Prior to that he had had no tuition at all. His condition was diagnosed as the result of intrauterine injury to the central nervous system, deaf-mutism, congenital cataract in both eyes. His hearing was reduced by 80 decibels. He still had some residual vision and could count on his fingers if he held them up in front of his face. From birth he had also suffered from fish-skin disease which reduced the tactile sensitivity in his fingers.

When he came to the home Semyon had some self-care skills and he understood a few natural gestures such as: cat, sleep, get up, dress, wash.

During his first year of instruction the box. was given exercises to develop his skills of self-care. He learnt to put on appropriate clothes at different times of the day and for different activities: he soon did not need reminding to put on his sports outfit for physical training sessions, or to put on his overalls for work sessions. At the end of the year he knew how to brush his teeth and wash his feet before going to bed and was able to make his bed tidily. He also learnt to take part in certain group activities contributing to the running of the household: he helped tidy up the room he shared with other pupils, learnt to water indoor plants and to tidy articles on the shelves in his cupboard and bedside locker.

The boy was also taught to understand a large number of new signs. Later he came to use signs independently. While communicating with him through signs, his teacher also started to introduce a number of short dactylic words and some dactylic letters.

The impaired tactile sensitivity in Semyon’s fingers made it harder than usual to teach this particular boy. to read a script consisting of raised letters. However, special aids helped him surmount even this difficulty.

During his second year Semyon began to have regular lessons in verbal language: in “conversation” (finger-spelling) and writing (Braille script).

Lida A. came to the home at the age of eight. Her diagnosis read: congenital injury to the central nervous system; microphthalmia of the right eye, horizontal nystagmus in both eyes, chorioretinitis, the acuity of vision in the eye that still functioned was 0.03 (with a correction 0.08); deaf-mutism.

Tonal audiometry revealed the following hearing loss:

| Frequencies in Hz | Hearing Loss in Decibels |

| 250 | 70 |

| 500 | 75 |

| 1,000 | 80 |

| 2,000 | 80 |

| 3,000 | 85 |

| 4,000 | 90 |

Before Lida came to the home for the deaf-blind she had received tuition in a group of pre-school pupils at a home for the deaf. She had mastered skills of self-care. When she first came to our home, Lida communicated with people via signs referring to various everyday and domestic activities (eat, sleep, wash, go). She had not mastered verbal speech in either its manual or written forms. Initially, she hardly communicated at all with the other children because she had a command of only very few signs, and could not use finger-spelling at all. In her special lessons to promote communication skills Lida was given simultaneous instruction in signs, manual speech and writing. She was taught signs denoting objects, then their dactylic names modelled on special cards with raised shapes.

During her first year of instruction Lida learnt to find her way about her room and the yard most efficiently. She learnt to make her bed tidily and to wash small articles of clothing. She was given her initial instruction in the work skills required for sewing and learnt to hem handkerchiefs. She learnt to communicate with others using sign speech.

By the end of her second year of instruction Lida described an outing at the following level: “September 1st. I saw field. Rye growing. Ear. Grain. Bread. Mushrooms, nuts in wood.”

In the second year of her instruction Lida learnt to answer with dactylic words questions concerning what she had been eating, where she had been, what she had seen during a walk or outing. After paying a visit to Moscow during that year she wrote the following composition: “We went to Moscow. We saw Metro. We went to Pioneers’ Club. Many children in club. I saw many toys.”