To sum up the data given earlier on this problem we shall confine ourselves to the picture of the movement of workers over the territory of European Russia. Such a picture is supplied by the Department of Agriculture’s publication[1] based on statements by employers. The picture of the movement of workers will give a general idea of how the home market for labour-power is being formed; using the material of the publication mentioned, we have only tried to draw a distinction between the movement of agricultural and non-agricultural workers, although the map appended to the publication and illustrating the movement of the workers does not show this distinction.

The main movements of agricultural workers are the following: 1) From the central agricultural gubernias to the southern and eastern outer regions. 2) From the northern black-earth gubernias to the southern black-earth gubernias, from which, in turn, the workers go to the border regions (cf. Chapter III, § IX, pp. 237-238 and § X, pp. 242-243). 3) From the central agricultural gubernias to the industrial gubernias (cf. Chapter IV, § IV, pp. 270-271). 4) From the central and the south-western agricultural gubernias to the area of sugar-beet plantations (workers come in part to these places even from Galicia).

The main movements of non-agricultural workers are: 1) To the metropolitan cities and the large towns, chiefly from the non-agricultural gubernias, but to a considerable degree also from the agricultural gubernias. 2) To the industrial area, to the factories of Vladimir, Yaroslavl and other gubernias from the same localities. 3) To new centres of industry or to new branches of industry, to centres of non-factory industry, etc. These include the movement: a) to the beet-sugar refineries of the south-western gubernias; b) to the southern mining area; c) to jobs at the docks (Odessa, Rostov-on-Don, Riga, etc.); d) to the peat beds in Vladimir and other gubernias; e) to the mining and metallurgical area of the Urals; f) to the fisheries (Astrakhan, the Black Sea, Azov Sea, etc.); g) to shipbuilding, sailoring, lumbering and rafting jobs, etc.; h) to jobs on the railways, etc.

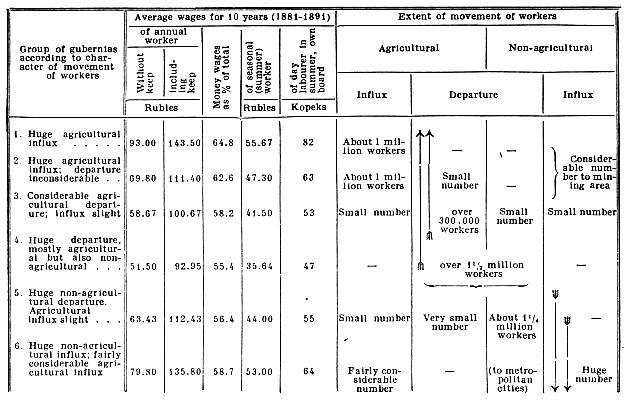

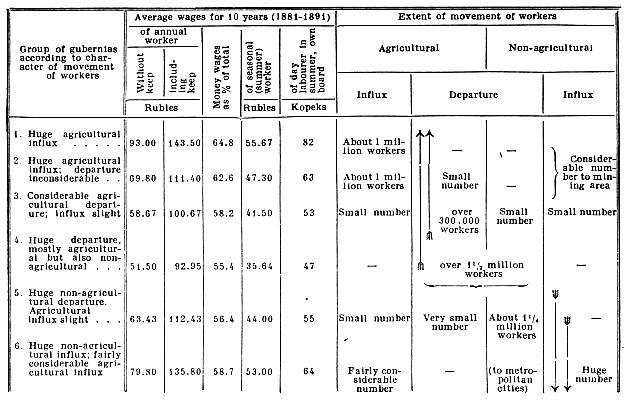

These are the main movements of the workers which, according to the evidence of employers, more or less materially affect the conditions of labour hire in the various localities. To appreciate more clearly the significance of these movements, let us compare them with the data on wages in the various districts from and to which the workers migrate. Confining ourselves to 28 gubernias in European Russia, we divide these into 6 groups according to the character of the movement of workers, and get the following data:[2]

This table clearly shows us the basis of the process that creates the home market for labour-power and, consequently, the home market for capitalism. Two main areas, those most developed capitalistically, attract vast numbers of workers: the area of agricultural capitalism (the southern and the eastern outer regions), and the area of industrial capitalism (the metropolitan and the industrial gubernias). Wages are lowest in the area of departure, the central agricultural gubernias, where capitalism, both in agriculture and in industry, is least developed[3]; in the influx areas, on the other hand, wages rise for all types of work, as does also the percentage of money wage to total wage, i.e., money economy gains ground at the expense of natural economy. The intermediary areas, those between the areas of the greatest influx (and of the highest wages) and the area of departure (and of the lowest wages) reveal the mutual replacement of workers to which reference was made above: workers leave in such numbers that in the places of departure a shortage of labour is created which attracts workers from the more “poorly paid” gubernias.

In essence, the two-sided process shown in our table—that of the diversion of population from agriculture to industry (industrialisation of the population) and of the development of commercial-industrial, capitalist agriculture (industrialisation of agriculture)—epitomises all that has been said above on the formation of a home market for capitalist society. The home market for capitalism is created by the parallel development of capitalism in agriculture and in industry,[4] by the formation of a class of rural and industrial employers, on the one hand, and of a class of rural and industrial wage-workers, on the other. The main streams of the movement of workers show the main forms of this process, but by far not all the forms; in what has gone before we have shown that the forms of this process differ in peasant and in landlord farming, in the different areas of commercial agriculture, in the different stages of the capitalist development of industry, etc.

How far this process is distorted and confused by the representatives of Narodnik economics is seen most clearly in § VI of Part 2 of Mr. N.–on’s Sketches, which bears the significant heading: “The Influence of the Redistribution of the Social Productive Forces upon the Economic Position of the Agricultural Population.” Here is how Mr. N.–on pictures this “redistribution”: “. . . In capitalist . . . society, every increase in the productive power of labour entails the ‘freeing’ of a corresponding number of workers, who are compelled to seek some other employment; and since this occurs in all branches of production, and this ‘freeing’ takes place over the whole of capitalist society, the only thing left open to them is to turn to the means of production of which they have not yet been deprived, namely, the land” (p. 126). . . . “Our peasants have not been deprived of the land, and that is why they turn their efforts towards it. When they lose their employment in the factory, or are obliged to abandon their subsidiary domestic occupations, they see no other course but to set about the increased exploitation of the soil. All Zemstvo statistical returns note the fact that the area under cultivation is growing. . .” (128).

As you see, Mr. N.–on knows of quite a special sort of capitalism that has never existed anywhere and that no economist could conceive of. Mr. N.–on’s capitalism does not divert the population from agriculture to industry, does not divide the agriculturists into opposite classes. Quite the contrary. Capitalism “frees” the workers from industry and there is nothing left for “them” to do but to turn to the land, for “our peasants have not been deprived of the land”!! At the bottom of this “theory,” which originally “redistributes” in poetic disorder all the processes of capitalist development, lie the ingenious tricks of all Narodniks which we have examined in detail previously: they lump together the peasant bourgeoisie and the rural proletariat; they ignore the growth of commercial farming; they concoct stories about “people’s” “handicraft industries” being isolated from “capitalist” “factory industry,” instead of analysing the consecutive forms and diverse manifestations of capitalism in industry.

[1] “Agricultural and statistical information based on material obtained from farmers. Vol. V. Hired Labour on private-landowner farms and the movement of workers, according to a statistical and economic survey of agriculture and industry in European Russia.” Compiled by S. A. Korolenko. Published by Department of Agriculture and Rural Industries, St. Petersburg, 1892.—Lenin

[2] The other gubernias are omitted in order not to complicate our exposition with data that contribute nothing new to the subject under examination; furthermore, the other gubernias are either untouched by the main, mass, movements of workers (Urals, the North) or have their specific ethnographical, administrative and juridical features (the Baltic gubernias, the gubernias in the Jewish Pale of Settlement, the Byelorussian gubernias, etc.). Data from the publication cited above. Wage figures are the average for the gubernias in the respective groups; the day labourer’s summer wage is the average for three seasons: sowing, haymaking and harvesting. The areas (1 to 6) include the following gubernias: 1) Taurida, Bessarabia and Don; 2) Kherson, Ekaterinoslav, Samara, Saratov, Orenburg; 3) Simbirsk, Voronezh, Kharkov; 4) Kazan, Penza, Tambov, Ryazan, Tula, Orel, Kursk; 5) Pskov, Novgorod, Kaluga, Kostroma, Tver, Nizhni-Novgorod; 6) St. Petersburg, Moscow, Yaroslavl, Vladimir.—Lenin

[3] Thus, the peasants flee in mass from the localities where patriarchal economic relationships are most prevalent, where labour-service and primitive forms of industry are preserved to the greatest extent, to localities where the “pillars” are completely decayed. They flee from “people’s production” and pay no heed to the chorus of voices from “society” following in their wake. In this chorus two voices can be clearly distinguished: “They have little attachment!” comes the menacing bellow of the Black-Hundred Sobakevich.[5] “They have insufficient allotment land!” is the polite correction of the Cadet Manilov.—Lenin

[4] Theoretical economics established this simple truth long ago. To say nothing of Marx, who pointed directly to the development of capitalism in agriculture as a process that creates a “home market for industrial capital” (Das Kapital, I 2, S. 776, Chapter 24, Sec. 5), [6] let us refer to Adam Smith. In chapter XI of Book I and Chapter IV of Book III of The Wealth of Nations, he pointed to the most characteristic features of the development of capitalist agriculture and noted the parallelism of this process with the process of the growth of the towns and the development of industry.—Lenin

[5] Sobakevich– a character in Gogol’s Dead Souls, the personification of the bullying, tight-fisted landlord. [p. 589]

[6] Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. I, Moscow, 1958, Chapter 30 (p. 745). [p. 590]

| | |

| | | | | | |