We now pass to the central black-earth belt, to Saratov Gubernia. We take Kamyshin Uyezd, the only one for which a fairly complete classification of the peasants according to draught animals held is available.[1]

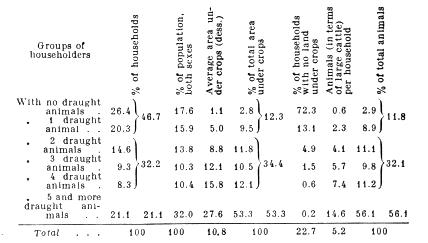

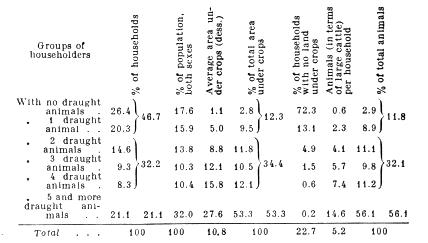

Here are the data for the whole uyezd (40,157 households, 263,135 persons of both sexes. Area under crops, 435,945 dessiatines, i.e., 10.8 dessiatines per “average” household):

Thus, here again we see the concentration of land under crops in the hands of the big crop growers: the well-to-do peasantry, constituting only a fifth of the households (and about a third of the population),[2] hold more than half the total area under crops (53.3%), the size of this area clearly indicating the commercial character of the farming: an aver age of 27.6 dess. per household. The well-to-do peasantry have also a considerable number of animals per household: 14.6 head (in terms of cattle, i.e., counting 10 head of small domestic animals for one of cattle), and of the total number of peasants’ cattle in the uyezd, nearly 3/5 (56%) is concentrated in the hands of the peasant bourgeoisie. At the opposite pole in the countryside, we find the opposite state of affairs; the complete dispossession of the bottom group, the rural proletariat, who in our example comprise a little less than 1/2 of the households (nearly 1/3 of the population), but who have only 1/8 of the total area under crops, and even less (11.8%) of the total number of animals. These are mainly allotment-holding farm labourers, day labourers and industrial workers.

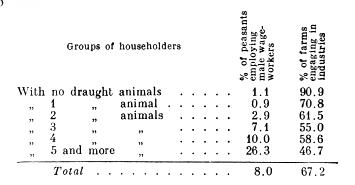

Side by side with the concentration of crop areas and with the enhancement of the commercial character of agriculture there takes place its transformation into capitalist agriculture. We see the already familiar phenomenon: the sale of labour-power in the bottom groups and its purchase in the top ones.

Here an important explanation is needed. P. N. Skvortsov has quite rightly noted in one of his articles that Zemstvo statistics attach far too “wide” a meaning to the term “industry” (or “employments”). In fact, all sorts of occupations engaged in by the peasants outside their allotments are assigned to the category of “industries”; factory owners and workers, owners of flour mills and of melon fields, day labourers, regular farm labourers; buyers-up, traders and unskilled labourers; lumber-dealers and lumbermen; building contractors and building workers; members of the liberal professions, clerks, beggars, etc., all these are “industrialists”! This barbarous misuse of words is a survival of the traditional—and we have the right even to say: official—view that the “allotment” is the “real,” “natural” occupation of the muzhik, while all other occupations are assigned indiscriminately to “outside” industries. Under serfdom this use of the word had its raison d’ etre, but now it is a glaring anachronism. Such terminology is retained partly because it harmonises wonderfully with the fiction about an “average” peasantry and rules right out the possibility of studying the differentiation of the peasantry (particularly in those places where peasant “outside” occupations are numerous and varied. Let us remind the reader that Kamyshin Uyezd is a noted centre of the sarpinka industry[11]). The processing[3] of household returns on peasant farming will be unsatisfactory so long as peasant “industries” are not classified according to their economic types, so long as among the “industrialists” employers are not separated from wage-workers. This is the minimum number of economic types without discriminating between which economic statistics cannot be regarded as satisfactory. A more detailed classification is, of course, desirable; for example; proprietors employing wage-workers—proprietors not employing wage-workers—traders, buyers-up, shopkeepers, etc., artisans, meaning industrialists who work for customers, etc.

Coming back to our table, let us observe that after all we had some right to consider “industries” as being the sale of labour-power, for it is usually wage-workers who predominate among peasant “industrialists.” If it were possible to single the wage-workers out of the latter, we would, of course, obtain an incomparably smaller percentage of “industrialists” in the top groups.

As to the data regarding wage-workers, we must note here the absolutely mistaken character of Mr. Kharizomenov’s opinion that the “short-term hire[of workers] for reaping, mowing and day labouring, which is too widespread a phenomenon, cannot serve as a characteristic criterion of the strength or weakness of a farm” (p. 46 of “Introduction” to the Combined Returns). Theoretical considerations, the example of Western Europe, and the facts of Russia (dealt with below) compel us, on the contrary, to regard the hiring of day labourers as a very characteristic feature of the rural bourgeoisie.

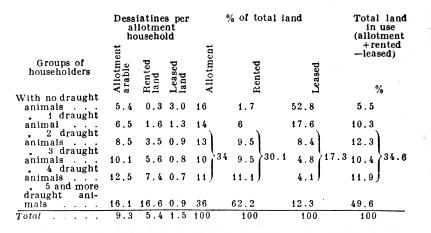

Lastly, as regards rented land, the data show, here too, the same concentration of it in the hands of the peasant bourgeoisie. Let us note that the combined tables of the Saratov statisticians do not show the number of peasants who rent land and lease it out, but only the total land rented and leased out[4]; we have, therefore, to determine the amount of land rented and leased per existing, and not per renting household.

Thus we see, here too, that the wealthier the peasants the more they rent land, despite the fact that they are better provided with allotment land. Here too we see that the well-to-do are ousting the middle peasantry, and that the role of allotment land in peasant farming tends to diminish at both poles of the countryside.

Let us examine in greater detail these data on land renting. With them are connected the very interesting and important investigations and arguments of Mr. Karyshev (quoted Results) and Mr. N.–on’s “corrections” to them.

Mr. Karyshev devotes a special chapter (III) to “the dependence of land renting on the prosperity of the lessees.” The general conclusion he arrives at is that, “other things being equal, the struggle for rentable land tends to go in favour of the better-off” (p. 156). “The relatively more prosperous households . . . push the less prosperous ones into the background” (p. 154). We see, consequently, that the conclusion drawn from a general review of Zemstvo statistical data is the same as that to which we are led by the data we are studying. Moreover, a study of the dependence of the amount of rented land on the size of the allotment led Mr. Karyshev to the conclusion that classification according to allotment “obscures the meaning of the phenomenon that interests us” (p. 139): “land renting . . . is more resorted to by a) the categories that are worse provided with land, but by b) the groups within them that are better provided. Evidently, we have here two diametrically opposed influences, the confusion of which prevents the understanding of either” (ibid.). This conclusion follows naturally if we consistently adhere to the viewpoint that distinguishes the peasant groups according to economic strength; we have seen everywhere in our data that the well-to-do peasants grab rentable land, despite the fact that they are better provided with allotment land. It is clear that the degree of prosperity of the household is the determining factor in the renting of land, and that this factor merely undergoes a change but does not cease to be determining, with the change in the conditions of land allotment and renting. But, although Mr. Karyshev investigated the influence of “prosperity,” he did not adhere consistently to the viewpoint mentioned, and therefore characterised the phenomenon inaccurately, speaking of the direct connection between the degree to which the lessee is supplied with land and the renting of land. This is one point. Another point is that the one-sidedness of Mr. Karyshev’s investigation prevented him from appraising the full significance of the way rentable land is grabbed by the rich peasants. In his study of “non-allotment renting”, he limits himself to summarising the Zemstvo statistics on land renting, without taking account of the lessees’ own farms. Naturally, with such a method of study, a more formal one, the problem of the relation between land renting and the “prosperity,” of the commercial character of land renting could not be solved. Mr. Karyshev, for example, was in possession of the same data on Kamyshin Uyezd as we are, but he limited himself to reproducing absolute figures only of land renting (see Appendix No. 8, p. XXXVI) and to calculating the average amount of rented land per allotment holding household (text, p. 143). The concentration of land renting in the hands of the well-to-do peasants, its industrial character, its connection with land leasing by the bottom group of the peasantry, were all overlooked. Thus, Mr. Karyshev could not but see that the Zemstvo statistics refute the Narodnik notion of land renting and show that the poor are ousted by the well-to-do peasants; but he gave an inaccurate description of this phenomenon, did not study it from all sides and came into conflict with the data, repeating the old song about the “labour principle,” etc. But even the mere statement of the fact of economic discord and conflict among the peasantry seemed heresy to the Narodniks, and they proceeded to “correct” Mr. Karyshev in their own way. Here is how Mr. N.–on does it, “using,” as he says (p. 153, note), Mr. N. Kablukov’s arguments against Mr. Karyshev. In § IX of his Sketches, Mr. N.–on discusses land renting and the various forms it assumes. “When a peasant,” he says, “has sufficient land to enable him to obtain his livelihood by tilling his own, he does not rent any land” (152). Thus, Mr. N.–on flatly denies the existence of entrepreneur activity in peasant land renting and the grabbing of rentable land by rich peasants engaged in commercial crop growing. His proof? Absolutely none: the theory of “people’s production” is not proved, but laid down as law. In answer to Mr. Karyshev, Mr. N.–on quotes a table from the Zemstvo abstract for Khvalynsk Uyezd showing that “the number of draught animals being equal, the smaller the allotment the more must this deficiency be compensated by renting” (153),[5] and again, “if the peasants are placed in absolutely identical conditions as regards the possession of animals, and if they have sufficient workers in their households, then the smaller the allotment they have, the more the land they rent” (154). The reader will see that such “conclusions” are merely a quibble at Mr. Karyshev’s inaccurate formulation, that Mr. N.–on’s empty trifles simply obscure the issue of the connection between land renting and prosperity. Is it not self-evident that where an equal number of draught animals is possessed, the less land a household has, the more it rents? That goes without saying, for it is the very prosperity whose differences are under discussion that is taken as equal. Mr. N.–on’s assertion that peasants with sufficient land do not rent land is not in any way proved by this, and his tables merely show that he does not understand the figures he quotes: by comparing the peasants as to amount of allotment land held, he brings out the more strikingly the role of “prosperity” and the grabbing of rentable land in connection with the leasing of land by the poor (leasing it to these same well-to-do peasants, of course.)[6] Let the reader recall the data we have quoted on the distribution of rented land in Kamyshin Uyezd; imagine that we have singled out the peasants with “an equal number of draught animals” and, dividing them into categories according to allotment and into subdivisions according to the number of persons working, we declare that the less land a peasant has, the more he rents, etc. Does such a method result in the disappearance of the group of well-to-do peasants? Yet Mr. N.–on, with his empty phrases, has succeeded in bringing about its disappearance and has been enabled to repeat the old prejudices of Narodism.

Mr. N.–on’s absolutely useless method of computing the land rented by peasants per household according to groups with 0, 1, 2, etc., persons working is repeated by Mr. L. Maress in the book The Influence of Harvests and Grain Prices, etc. (I, 34). Here is a little example of the “averages” boldly employed by Mr. Maress (as by the other contributors to this book, written from a biased Narodnik point of view). In Melitopol Uyezd, he argues, the amount of rented land per renting household is 1.6 dess. in households having no working males, 4.4 dess. in households having one working male, 8.3 in households having two, and 14.0 in households having three (p. 34). And the conclusion is that there is an “approximately equal per-capita distribution of rented land”!! Mr. Maress did not think it necessary to examine the actual distribution of rented land according to groups of households of different economic strength, although he was in a position to learn this both from Mr. V. Postnikov’s book and from the Zemstvo abstracts. The “average” figure of 4.4 dess. of rented land per renting household in the group of households having one working male was obtained by adding together such figures as 4 dess. in the group of households cultivating 5 to 10 dess. and with 2 to 3 draught animals, and 38 dess. in the group of households cultivating over 50 dess. of land and with 4 and more draught animals. (See Returns for Melitopol Uyezd, p. D.10-11.) It is not surprising that by adding together the rich and the poor and dividing the total by the number of items added, one can obtain “equal distribution” wherever desired!

Actually, however, in Melitopol Uyezd 21% of the households, the rich ones (those with 25 dess. and more under crops), comprising 29.5% of the peasant population, account—despite the fact that they are best provided with allotment and purchased land—for 66.3% of the total rented arable (Returns for Melitopol Uyezd, p. B. 190-194). On the other hand, 40% of the households, the poor ones (those with up to 10 dess. under crops), comprising 30.1 % of the peasant population, account—despite the fact that they are worst provided with allotment and purchased land—for 5.6% of the total rented arable. As can be seen, this closely resembles “equal per-capita distribution”!

Mr. Maress bases all his calculations of peasant land-renting on the “assumption” that “the renting households are mainly in the two groups worst provided” (provided with allotment land); that “among the renting population there is equal per capita (sic!) distribution of rented land”; and that “the renting of land enables the peasants to pass from the groups worst provided to those best provided” (34-35). We have already shown that all these “assumptions” of Mr. Maress directly contradict the facts. Actually, the very contrary is the case, as Mr. Maress could not but have noted, had he—in dealing with inequalities in economic life (p. 35)—taken the data for the classification of households according to economic indices (instead of according to allotment tenure), and not limited himself to the unfounded “assumption” of Narodnik prejudices.

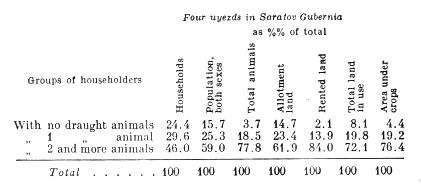

Let us now compare Kamyshin Uyezd with other uyezds in Saratov Gubernia. The ratios between the peasant groups are everywhere the same, as is shown by the following data for the four uyezds (Volsk, Kuznetsk, Balashov and Serdobsk) in which, as we have said, the middle and the well-to-do peasants are combined:

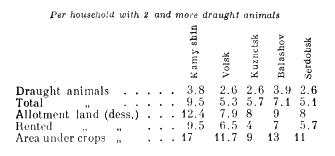

Hence, we see everywhere the ousting of the poor by the prosperous peasants. But in Kamyshin Uyezd the well-to-do peasantry are more numerous and richer than in the other uyezds. Thus, in five uyezds of the gubernia (including the Kamyshin Uyezd) the households are distributed according to draught animals held as follows: with no draught animals—25.3%; with 1 animal—25.5%; with 2—20%; with 3—10.8%; and with 4 and more—18.4%, whereas in Kamyshin Uyezd, as we have seen, the well-to-do group is larger, and the badly-off group somewhat smaller. Further, if we combine the middle and well-to-do peasantry, i.e., if we take the households with 2 draught animals and more, we get the following data for the respective uyezds:

This means that in Kamyshin Uyezd the prosperous peasants are richer. This uyezd is one of those with the greatest abundance of land: 7.1 dess. of allotment land per registered person,[12] male, as against 5.4 dess. for the gubernia. Hence, the land-abundance of the “peasantry” merely means the greater numbers and greater wealth of the peasant bourgeoisie.

In concluding this review of the data for Saratov Gubernia, we consider it necessary to deal with the classification of the peasant households. As the reader has probably observed, we reject a limine[7] any classification according to allotment and exclusively employ classification according to economic strength (draught animals, area under crops). The reasons for adopting this system must be given. Classification according to allotment is far more widespread in our Zemstvo statistics, and in its defence the two following, at first sight very convincing, arguments are usually advanced.[8] It is said, firstly, that to study the life of the agricultural peasants it is natural and necessary to classify them according to land. This argument ignores a fundamental feature of Russian life, namely, the unfree character of allotment-land tenure, in that by force of law it bears an equalitarian character, and that the purchase and sale of allotment land is hindered in the extreme. The whole process of the differentiation of the agricultural peasantry is one of real life evading these legal bounds. In classifying the peasants according to allotment, we lump together the poor peasant who leases out land and the rich peasant who rents or buys land; the poor peasant who abandons the land and the rich peasant who “gathers” land; the poor peasant who runs his most wretched farm with an insignificant number of animals and the rich peasant who owns many animals, fertilises his soil, introduces improvements., etc., etc. In other words, we lump together the rural proletarian and the members of the rural bourgeoisie. The “averages” thus obtained obscure the differentiation, and are therefore purely fictitious.[9] The combined tables of the Saratov statisticians described above enable us to demonstrate clearly the uselessness of classification according to allotment. Take, for example, the category of non-allotment peasants in Kamyshin Uyezd (see Combined Returns, p. 450 and foll., the Returns for Kamyshin Uyezd, Vol. XI, p. 174 and foll.). The compiler of the Combined Returns, in describing this category, says that the area under crops is “very negligible” (“Introduction”, p. 45), i.e., he assigns it to the category of the poor. Let us take the tables. The “average” area under crops in this category is 2.9 dess. per household. But see how this “average” was reached: by adding together the big crop growers (18 dess. per household in the group with 5 and more draught animals; the households in this group constitute about 1/8 of the whole category, but they possess about half of this category’s area under crops) and the poor, the horseless peasants, with 0.2 dess. per household! Take the households employing farm labourers. There are very few of them in this category—77 in all, or 2.5%. But of these 77 there are 60 in the top group, in which the area cultivated is 18 dess. per household; and in this group the households employing farm labourers constitute 24.5%. Clearly, we obscure the differentiation of the peasantry, depict the propertyless peasants in a better light than they actually are (by adding the rich to them and striking averages), while, on the contrary, we depict the well-to-do peasants as being of lesser strength, because the category of peasants with large allotments includes, in addition to the majority, the well-off, also the badly-off (it is a known fact that even the large-allotment village communities always include indigent peasants). We are now clear, too, as to the incorrectness of the second argument in defence of classification according to allotment. It is argued that by such classification the indices of economic strength (number of animals, area under crops, etc.) always show a regular increase according to the increase in the size of the allotment. That is an undoubted fact, for the allotment is one of the major factors of well-being. Where, consequently, the peasants are large-allotment holders there are always more members of the peasant bourgeoisie and, as a result, the “average” allotment figures for the whole category are raised. All this, however, gives no grounds whatever for inferring that a method combining the rural bourgeoisie with the rural proletariat is correct.

We conclude: in systematising peasant household statistics one should not limit oneself to classification according to allotment. Economic statistics must necessarily take the scale and type of farm as the basis of classification. The indices for distinguishing these types should be taken in conformity with local conditions and forms of agriculture, while in dealing with extensive grain farming, one can limit oneself to classifying according to area under crops (or to the number of draught animals); under other conditions one must take account of the area under industrial crops, the technical processing of agricultural produce, the cultivation of root crops or of fodder grasses, dairy farming, vegetable growing, etc. When the peasantry combine agricultural and industrial occupations on a large scale, a combination of the two systems of classification is necessary, i.e., of classification according to the scale and type of agriculture, and of classification according to the scale and type of “industries.” The methods of summarising peasant household returns are not such a narrowly specific and second-rate problem as one might imagine at first sight. On the contrary, it will be no exaggeration to say that at the present time it is the basic problem of Zemstvo statistics. The completeness of household returns and the technique of collecting them[10] have reached a high degree of perfection, but owing to unsatisfactory summarising, a vast amount of most valuable information is simply lost, and the investigator has at his disposal merely “average” figures (for village communities, volosts, categories of peasants, size of allotment, etc.). But these “averages,” as we have seen already, and shall see later, are often absolutely fictitious.

[1] For the other four uyezds of this gubernia the classification according to draught animals held merges the middle and well-to-do peasantry. See Combined Statistical Returns for Saratov Gubernia, Part 1, Saratov, 1888. B. Combined Tables for Saratov Gubernia according to categories of peasants—The Saratov statisticians compiled their combined tables as follows: all the householders are divided into six categories according to size of allotment, each category is divided into six groups according to the number of draught animals, and each group is divided into four subdivisions according to the number of working males in the family. Summarised data are given only for the categories, so that we have to calculate those for the groups ourselves. We shall deal with the significance of this table later on.—Lenin

[2] Let us note that when classifying households according to economic strength, or to size of farm, we always get larger families among the well-to-do strata of the peasantry. This phenomenon points to the connection between the peasant bourgeoisie and large families, which receive a larger number of allotments; partly it shows the opposite: it indicates the lesser desire of the well-to-do peasantry to divide up the land. One should not, however, exaggerate the significance of large families among the well-to-do peasants, who, as our figures show, resort in the greatest measure to the employment of hired labour. The “family co-operation” of which our Narodniks are so fond of talking is thus the basis of capitalist co-operation.—Lenin

[3] We say “processing” because the data on peasant industries collected in the house-to-house censuses are very comprehensive and detailed.—Lenin

[4] The total amount of arable leased out in the uyezd is 61,639 dess., i.e., about 1/6 , of the aggregate allotment arable (377,305 dess.).—Lenin

[5] An exactly similar table is given by the statisticians for Kamyshin Uyezd. Statistical Returns for Saratov Gubernia, Vol. XI Kamyshin Uyezd, p. 249 and foll. We can just as well, therefore make use of the data for the uyezd we have taken.—Lenin

[6] That the data quoted by Mr. N.–on refute his conclusions has already been pointed to by Mr. P. Struve in his Critical Remarks.—Lenin

[7] At once.—Ed.

[8] See, for example, the introductions to the Combined Returns for Saratov Gubernia, to the Combined Returns for Samara Gubernia, and to Evaluation Returns for four uyezds of Voronezh Gubernia, and other Zemstvo statistical publications.—Lenin

[9] We take this rare opportunity of expressing our agreement with Mr. V. V., who in his magazine articles of 1885 and subsequent years welcomed “the new type of Zemstvo statistical publications,” namely, the combined tables, which make it possible to classify household data not only according to allotment, but also according to economic strength. “The statistical data,” wrote Mr. V. V. at that time, “must be adapted to the groups themselves and not to such a conglomeration of the most diverse economic groups of peasants as the village or the village community” (V. V., “A New Type of Local Statistical Publication,” pp. 189 and 190 in Severny Vestnik [Northern Herald], 1885, No. 3. Quoted in the “Introduction” to the Combined Returns for Saratov Gubernia, p. 36). To our extreme regret in none of his later works has Mr. V. V. made any effort to glance at the data on the various groups of the peasantry, and, as we have seen, he has even ignored the factual part of the book by Mr. V. Postnikov, who was probably the first to attempt the arrangement of the data according to the various groups of the peasantry and not according to “conglomerations of the most diverse groups”. Why is this?—Lenin

[10] About the technique of Zemstvo censuses see, in addition to the above-mentioned publications., the article by Mr. Fortunatov in Vol. I of Results of Zemstvo Statistical Investigation. Specimens of household registration cards are reproduced in the “Introduction” to the Combined Returns for Samara Gubernia and to the Combined Returns for Saratov Gubernia, in the Statistical Returns for Orel Gubernia (Vol. II, Yelets Uyezd) and in Material for the Statistical Survey of Perm Gubernia, Krasnoufimsk Uyezd, Vol. IV. The Perm registration card is particularly comprehensive.—Lenin

[11] Sarpinka—a thin striped or check cotton cloth; originally made in Sarepta.

[12] The registered males were those members of the male population of feudal Russia subject to the poll-tax (the peasantry and urban middle class were chiefly affected) and to this end were recorded in special censuses (so-called “registrations”). Such “registrations” took place in Russia from 1718 onwards; the tenth and last ”registration was made in 1857-1859.” In a number of districts redistribution of the land within the village communities took place on the basis of those recorded in the “registration” lists.

| | |

| | | | | | |