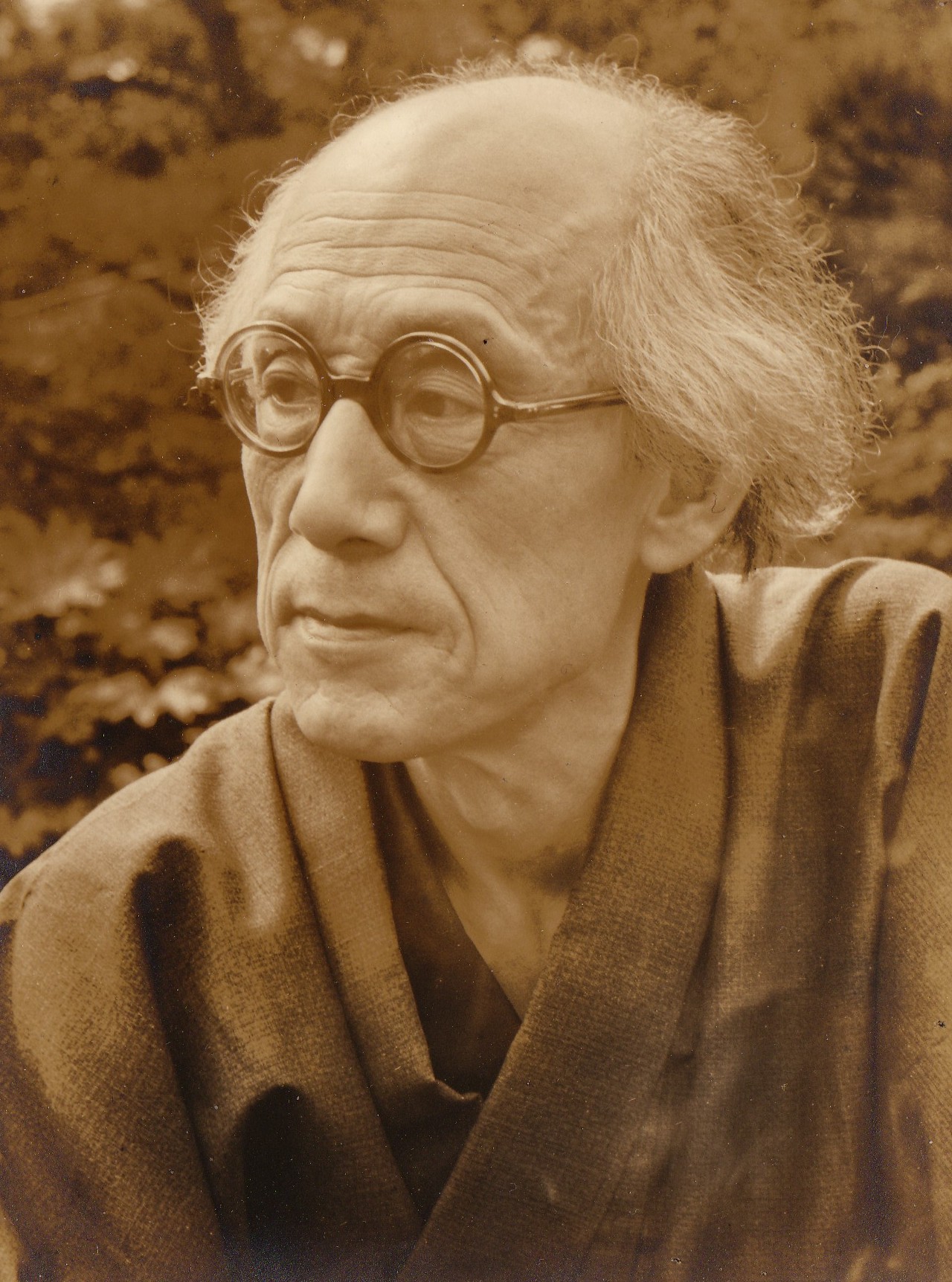

Samezō Kuruma

Source: Insert published with Marx-Lexikon Zur Politischen Ökonomie vol. 3, December 1969;

Translated: for marxists.org by Michael Schauerte;

CopyLeft: Creative Commons (Attribute & ShareAlike) marxists.org 2006.

The following discussion of Marx's method of political economy was published as an insert for the third volume of the Marx-Lexikon zur Politischen Ökonomie edited by Kuruma. For the Marx-Lexikon, Kuruma gathered together key passages from Marx's collected works, as well as passages written by Engels, in both the original German and translated Japanese, to clarify a number of key topics, such as "historical materialism," "crisis," "competition," and "money." The third volume, which the discussion below concerns, was the second of two volumes dealing with the topic of "method." As in the other volumes, Kuruma organized the passages under headings and subheadings, and underlined or highlighted in bold those parts of particular importance. Each of the 15 volumes also included an insert with a discussion between Kuruma and the others involved in the Marx-Lexikon regarding the topic at hand. The other names are indicated by initials because the text is an altered version of the actual discussion that took place, which involved Kuruma first introducing information on his editorial approach and then fielding questions from those present. The format was altered to make the content easier to understand.

C: OK, I'll begin. We are now publishing the second volume of Lexikon on the topic of method, but there were questions from those who read the first volume regarding why the passages were divided into two volumes, and how the two differ.

Kuruma: The reason for the two volumes, as you know, is that there was simply too much material for a single volume. It would have been preferable to have had just one volume, but given the need for two, the question became what areas each volume should cover. Simply put, the first volume, as can be seen from the table of contents, deals directly with the question of method itself, while the second volume concentrates on what seem to be the important points characterizing Marx's political economy that correspond to his method that were clarified in the first Lexikon volume. But this is a very broad overview, and quite abstract, so it probably has little substantial meaning.

C: I'm still a bit stuck. Could you give us a more substantial explanation?

Kuruma: I think that the only way to provide an explanation with more substantial meaning would be to explain the meaning of the relation between the headings in volume two and the method of Marx.

A: Perhaps we could first look at heading VI, entitled "Critique of Political Economy." It seems that here Professor Kuruma is seeking to elucidate what Marx means by his "critique of political economy."

Kuruma: That's right. Marx, instead of referring to his political economy as the "principles of political economy" or a "principle theory of principle economy," calls it a "critique of political economy." This is of course the case in his book A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, published in 1859, but even his later work Capital bears the subtitle: "A Critique of Political Economy," so he is declaring his work to be a criticism of political economy. The question naturally arises, therefore, regarding what Marx means by the expression "critique of political economy."

In A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, published in 1858, Marx provides critical examinations, at the end of chapters and sections, concerning how previous doctrines dealt with the issues he is addressing, so this title makes sense. But this is not the case in Capital, which raises the question of why Marx still added the subtitle "A Critique of Political Economy" to this latter work.

His letter to Lasalle cited at the beginning of the second volume of Lexikon on method is the most direct expression of what the expression "critique of political economy" means to Marx, and is therefore the most appropriate response to the question above, while at the same time being extremely important in terms of clarifying the fundamental characteristic of his view of political economy. This is why I positioned this passage at the beginning of the second volume.

In the letter, Marx writes: The work I am presently concerned with is a Critique of Economic Categories or, if you like, a critical exposé of the system of the bourgeois economy."

Here "the work I am presently concerned with" refers to Marx's book that was published the following year as A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy: Part One, but Marx says in the letter that this is first of all a "critique of economic categories." Here we learn that the "critique of political economy" essentially signifies a criticism of economic categories, not a critique of the theories of political economy. This is confirmed in this letter when Marx says that, "the critique and history of political economy and socialism would form the subject of another work."

C: But even if it is said that the "critique of political economy" inherently means a critique of economic categories, I think, to be clear, we then need to explain what is meant by a critique of economic categories.

Kuruma: Yes, you're right. This question of how we should understand the "critique of economic categories" is the next issue to consider.

Every economic category is a reflection in human consciousness of the specific relations of bourgeois production. When the given relations of production have developed to a certain degree, thus taking on a clear existence, they are naturally reflected within human consciousness, and come to be given a name so that economic categories are created. These categories, and thus the relations of production they express as well, in their totality form the economic structure of capitalist society -- as a living organic totality -- and as such there must be an internal relation between them, but their internal relation vis-a-vis this totality, as well as the internal relation between them, is not directly expressed in the economic categories. Rather, it seems as if the individual economic categories exist in the shape of mutually independent things. The internal connection between the categories is first clarified by criticizing the categories.

D: Was such a criticism of categories first carried out by Marx? If this is the case, how should we evaluate the work of the classical economists?

Kuruma: No, Marx wasn't the first. Such a criticism was also carried out to some extent by bourgeois political economy - when classical political economy was still capable of being scientific -- although it was limited by the narrow confines of a bourgeois perspective. Marx, for instance, in Theories of Surplus Value writes:

Classical political economy seeks to reduce the various fixed and mutually alien forms of wealth to their inner unity by means of analysis and to strip away the form in which they exist independently alongside one another. It seeks to grasp the inner connection in contrast to the multiplicity of outward forms. It therefore reduces rent to surplus profit, so that it ceases to be a specific, separate form and is divorced from its apparent source, the land. It likewise divests interest of its independent form and shows that it is a part of profit. In this way it reduces all types of revenue and all independent forms and titles under cover of which the non-workers receive a portion of the value of commodities, to the single form of profit. Profit, however, is reduced to surplus-value since the value of the whole commodity is reduced to labor; the amount of paid labor embodied in the commodity constitutes wages, consequently the surplus over and above it constitutes unpaid labor, surplus labor called forth by capital and appropriated gratis under various titles.

This was certainly a great achievement of classical political economy. This is why Marx also refers to the classical economists as "critical economists" in contrast to "vulgar" economists. At the same time, we should not forget that the criticism offered by classical political economy is restricted by the limitations of the bourgeois field of vision.

For example, classical political economy "reduces rent to surplus profit," shows that interest "is a part of profit, and "reduces all types of revenue and all independent forms and titles under cover of which the non-workers receive a portion of the value of commodities, to the single form of profit," and it was basically aware that profit is reducible to surplus-value that is based on surplus labor. Despite this, however, classical political economy was incapable of distinguishing this surplus-value from profit, and establishing it as a category that indicates the direct relations of production that are at its basis.

D: In other words, the critique of economic categories performed by the classical school had a limitation, and there was an inability to arrive at the more fundamental category of surplus-value through a criticism of the category of profit.

Kuruma: Yes. This is the reason they confused surplus-value and profit, and confused the rate of surplus-value with the rate of profit. Not only did they end up in a hopelessly confused and contradictory position, but they also failed to understand important economic laws.

D: Could you speak more specifically about the confusion and contradiction that the classical economists fell into, as well as the defects in their understanding of important economic laws?

Kuruma: I suppose the most obvious examples of this is the confusion and fatal contradiction that Ricardo fell into as a result of equating production price with value instead of developing the latter from the former, and the defect in his understanding of the law of the tendential fall of the profit rate, or even more importantly his confusion of surplus-value with profit and confusion of the rate of surplus-value with the rate of profit, which seem to be the concentrated expression of his theoretical errors. Needless to say, this confusion stemmed from the fact that he took the established category of profit as a given without subjecting it to a thorough criticism.

To be more specific, because Ricardo did not criticize the category of "profit" to establish the category of surplus-value (s) underlying it, he was unable to fundamentally distinguish between constant capital (c) and variable capital (v), and was therefore unable to distinguish between the rate of surplus-value (s/v) and the rate of profit (s/c+v), so that he also did not raise the question of the necessity of the transformation of surplus-value into profit.

A fundamental condition for capitalist production is the exclusive ownership of the means of production by the capitalist class (while workers are separated from these means of production and exist as wageworkers), and capitalists must first and foremost invest one part of their capital on the means of production. This capital value (c) invested in the means of production is an essential condition for capitalist production and the production of surplus-value, but this capital itself does not generate surplus-value. Surplus-value only emerges from the variable capital (v), i.e. the part of the capital invested to purchase labor-power. However, capital is essentially self-valorizing value, so constant capital is a "necessary evil" for capital. And various problems emerge from this fact.

First, there emerges the necessity of the transformation of surplus-value into profit, and the transformation of the rate of surplus-value into the rate of profit. Because surplus-value (s) is only created from the variable capital (v), it only has an inherent connection to this variable capital and cannot be created with constant capital. The constant capital may be called a "necessary evil" but it is indeed a necessary condition. In order for a capitalist to obtain surplus-value, capital must be invested not only for variable capital, but for constant capital as well. This means that surplus-value is necessarily manifested as the fruit of the entire capital (c+v), which is to say, in the form of profit. In this form, the inherent relations of production are concealed and expressed in a distorted form, but this is an unavoidable phenomenal form. At the same time, the rate of surplus-value (s/v), which expresses the original relations of production, is transformed into the form of the rate of profit.

Until the arrival of Marx, however, no one had clarified this. Classical political economy was aware that the source of profit is the surplus labor of the workers employed by a capitalist. For instance, Adam Smith writes:

The value which the workmen add to the materials, therefore, resolves itself in this case [when capitalistic production is carried out] into two parts, of which the one pays their wages, the other the profits of their employer upon the whole stock of materials and wages which he advanced[1].

Here Smith, on the one hand, is actually reducing profit to surplus-value ? i.e. the value created by surplus labor - but on the other hand he still calls this profit, and says that this profit stems from "the whole stock of materials and wages which [the capitalist] advanced." Here we can see a confusion between surplus-value and profit, with the two directly conflated because no consideration is given to the transformation of surplus-value into profit, but after saying this Smith goes on to write:

He could have no interest to employ them, unless he expected from the sale of their work something more than what was sufficient to replace his stock [i.e. capital] to him; and he could have no interest to employ a great stock rather than a small one, unless his profits were to bear some proportion to the extent of his stock[2].

Instead of scientifically tracing how surplus-value is manifested as profit, Smith grasps surplus-value, as is, as profit, and therefore is unable to clarify the differences between the rate of surplus-value and the rate of profit, or understand how the latter separates from the former. Smith, exhibiting the "interests" of capitalists, in a single bound and without scientifically tracing the formation of the average rate of profit proceeds directly to explain the existence of a general rate of profit. As a result, he ultimately falls into the vulgar view that the natural price of a commodity (its value expressed in money) is composed of three elements: wages, profit and rent. This view was opposed by Ricardo, who argued that the value of a commodity is not composed of these three elements but rather is determined by the labor-time necessary for production, and that this value of a commodity is divided up into these three parts, thus distributed to the three classes (wageworkers, capitalists and landowners). And to this extent Ricardo was correct. Meanwhile, however, he inherits the errors of Smith, from the confusion of surplus-value and profit, to premising the general rate of profit from the outset. Because of this, the contradictions that assume a hazy form in the case of the carefree Smith, become acute in the case of Ricardo, who sought in a mechanical fashion to thoroughly demonstrate the validity of the law of value, and this eventually brought about the collapse of the classical school as you know, so it is as if I'm preaching to the choir here, but I would like to add a few more words regarding this.

If the general rate of profit is taken as a given premise, the capitalist must sell his commodity at a price that is the sum of the cost expended on its production (Marx's "cost price") plus the average profit (i.e. cost price multiplied by the general rate of profit) -- and Marx calls this the commodity's "production price." This production price, however, does not coincide with value. Thus the problem involves elucidating the necessity of the transformation of value into production price by starting from the determination of value by labor, to clarify, based on the law of value, how surplus-value emerges, and then clarify the transformation of surplus-value and the rate of surplus-value into profit and the rate of profit, and also clarify the process of an equilibrium being achieved between the inevitable differences in profit rates between production sectors via competition. But bourgeois economists, who saw the relations of capitalist production as being supra-historical and natural, had no hope from the outset of achieving this.

D: I see. I can understand well your explanation but there is one issue that you did not explain in detail; namely, the defect in the classical economists' theory regarding the tendential fall in the rate of profit.

Kuruma: Oh, that's right.

It was already recognized a long time ago that with the accumulation of capital the rate of profit gradually falls. Economists made various attempts to clarify the ultimate cause of this, but every effort ended in failure. In part three of the third volume of Capital, Marx addresses this problem, elucidating that the cause of the tendential fall in the rate of profit is the rise in the organic composition of capital which inevitably accompanies the development of capitalist production, and he explains in the following manner why bourgeois political economy was unable to clarify this:

Simple as this law appears from the foregoing statements, all of political economy has so far had little success in discovering it, as we shall see in a later part. The economists perceived the phenomenon and cudgeled their brains in tortuous attempts to interpret it. Since this law is of great importance to capitalist production, it may be said to be a mystery whose solution has been the goal of all political economy since Adam Smith, the difference between the various schools since Adam Smith having been in the divergent approaches to a solution. When we consider, on the other hand, that up to the present political economy has been running in circles round the distinction between constant and variable capital, but has never known how to define it accurately; that it has never separated surplus-value from profit, and never even considered profit in its pure form as distinct from its different, independent components, such as industrial profit, commercial profit, interest, and ground-rent; that it has never thoroughly analyzed the differences in the organic composition of capital, and, for this reason, has never thought of analyzing the formation of the general rate of profit -- if we consider all this, the failure to. solve this riddle is no longer surprising[3].

Because prior economists, as I have already noted, did not thoroughly criticize economic categories and failed to clearly grasp the distinction between surplus-value and profit, they were also unable to grasp the fundamental distinction of capital from the perspective of the production of surplus-value - namely, the distinction between constant capital (c) and variable capital (v). Therefore, they also had no idea of the organic composition of capital (c/v) which is based upon this distinction, and naturally were unable to solve the riddle of the tendential fall in the rate of profit.

D: I understand the gist of what you are saying. Incidentally, in the passage just quoted, Marx says that the difference between the various schools of thought from the time of Smith could be said to lie in the different attempts to solve this problem of the tendential fall in the rate of profit. Could you elaborate on what sorts of schools of thought existed from the time of Smith regarding this problem?

Kuruma: I'm not familiar with all of the details regarding this myself, but the representative thinkers would be Smith and Ricardo. Smith thought that the rate of profit gradually falls because the accumulation of capital leads to more intense competition, which results in wage appreciation, and he discusses this in various parts of The Wealth of Nations. In chapter 21 of Principles of Political Economy, entitled "Effect of Accumulation on Profits and Interest," Ricardo counters this view held by Smith, arguing instead that the appreciation of wages due to the accumulation of capital is limited to the case where capital accumulation outstrips the increase in the population of workers, and although such a case might occur, it is a temporary situation which cannot explain a permanent fall in the rate of profit. Ricardo argues that this permanent fall in the profit rate must be explained by a permanent appreciation of wages, and that the cause of this wage appreciation must be sought in the law of diminishing returns that inevitably occurs when there is an increase in the production of agricultural goods that make up the bulk of the workers' materials of livelihood. But this view of Ricardo is also mistaken. Marx explains in detail how Ricardo's view is mistaken, but it would take up too much time to enter this discussion here. Readers can consult Part II of Theories of Surplus Value.

D: So because the criticism of economic categories was insufficient, previous political economy, even classical political economy, was unable to understand the secret of the tendential fall of the rate of profit. I can understand this well. Are there any other important examples you could offer?

Kuruma: One example is the inability to criticize the category of wages to grasp the underlying value of labor-power. Regarding this, Marx writes:

Classical Political Economy borrowed from every-day life the category "price of labor" without further criticism, and then simply asked the question, how is this price determined?...What economists therefore call value of labor, is in fact the value of labor-power...it accepted uncritically the categories "value of labor," "natural price of labor," etc.,. as final and as adequate expressions for the value-relation under consideration, and was thus led, as will be seen later, into inextricable confusion and contradiction, while it offered to the vulgar economists a secure basis of operations for their shallowness, which on principle worships appearances only. ...

For the rest, in respect to the phenomenal form, "value and price of labor," or "wages," as contrasted with the essential relation manifested therein, viz., the value and price of labor-power, the same difference holds that holds in respect to all phenomena and their hidden substratum. The former appear directly and spontaneously as current modes of thought; the latter must first be discovered by science. Classical Political Economy nearly touches the true relation of things, without, however, consciously formulating it. This it cannot, so long as it sticks in its bourgeois skin[4].

Marx thoroughly carries out a criticism of such "bourgeois economic categories" by adopting a critical standpoint toward bourgeois production itself.

D: So this is why Marx calls his system of political economy a "critique of political economy"?

Kuruma: Yes.

D: Incidentally, in the February 22, 1858 letter to Lasalle, which you cited earlier, Marx, after noting that "the work I am presently concerned with is a Critique of Economic Categories," says that it could also be called "a critical exposé of the system of the bourgeois economy," and goes on to say that "it is at once an exposé and, by the same token, a critique of the system." How should we understand this way of using a different form of expression, as well as the relation between these various definitions?

Kuruma: As I mentioned before, the various economic categories are themselves nothing more than a reflection in human consciousness of the specific relations of bourgeois production. And the various relations of bourgeois production in their totality form the economic structure of capitalist society, its organic living totality, and as such there should be a reciprocal internal connection between these relations, but this internal connection is not directly expressed in the case of the economic categories. Rather, the individual categories appear to exist independent of each other. It is only through criticizing these categories that we can first clarify the internal connection between them, and therefore the connection of each category to their totality, in order to understand how each, as moments, form a system in their totality.

D: Related to this point, I recall that Professor Kuruma once said that he had a great interest in the section "Logic as a Criticism of Categories" in Kazuto Matsumura's (1905-1977) Heegeru no ronri-gaku (Hegel's Logic).

Kuruma: Yes, I did. But when reading the various passages, we need to be aware of both the similarities between Hegel and Marx regarding the relation of a critique of categories to a theoretical system, while at the same time clarifying the essential differences between them.

As we can see in the first volume of Lexikon on method, Marx, in his afterword to the second edition of Capital, after raising the issue of the method of investigation and the method of presentation, writes: "Only after this work [of inquiry] has been done can the real movement be appropriately presented. If this is done successfully, if the life of the subject-matter is now reflected back in the ideas, then it may appear as if we have before us an a priori construction." Because of how much this appears to be an priori construction, if only this is focused upon, one will be tempted to interpret the system in Capital as an application of Hegel's system from the Science of Logic. Unlike Hegel, however, in the case of Marx the issue centers on elucidating the system of the capitalist society, which is a real historical entity, so the structure of his theoretical system that seems a priori at first glance is in fact premised on the investigative process, or so-called "descending path," regarding actually existing thing. In the course of this descending path, Marx, unlike the formal abstraction of classical political economy, "appropriates the material in detail, to analyze its different forms of development and to track down their inner connection." In other words, for Marx, the criticism of the economic categories that indicate the various relations of bourgeois production is originally carried out in the downward path (investigation), so the structure of the system via the criticism of categories - the structure of the system that appears at first glance to be a priori and to develop on its own through the internal contradictions of the categories - is in fact not a priori but rather what could be called the reverse side of the process of investigation. Thus, if the method of investigation is not correct, the descriptive method in the upward path, and the structure of the theoretical system, will not fare well. This was the also case for Ricardo, who occupies the pinnacle of classical political economy, not to mention vulgar political economy which confines itself to the world of phenomena. For more on this, the reader can consult subheading 8 ("Scientific Insufficiency of Ricardo's Method of Inquiry, and the Mistaken, Structure-less Method of Presentation in his Principles that Stems from This") in the first volume of Lexikon on method, particularly entry [10] in the first volume of Lexikon on method. Our discussion in the insert for this first volume may also be useful for coming to a deeper understanding of this.

Kuruma: There is another fundamental difference between Hegel's system and Marx's system. Part One (Logic) of Hegel's Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences concludes fortuitously with the Absolute Idea, and the Encyclopedia as a whole ends with the Absolute Spirit (see subheading 37 "Contradiction between Method and System in Case of Hegel: Method is Sacrificed for System" in the first Lexikon volume on the topic of method). Compared to this, Marx ends Book [volume] One of Capital with a chapter entitled "Historical Tendency of Capitalist Accumulation" (for more on the problems raised there see entries [139] and [140] in the first volume of Lexikon on method as well as chapter 25 of Capital entitled "The Modern Theory of Colonization" which was added to the end following the chapter just mentioned); and Book [volume] Three ends with a chapter entitled "Classes," although according to Engels' preface to this work, "there only exists the beginning" of this final chapter, and he notes that the original plan "was to treat of the three major classes of developed capitalist society -- the landowners, capitalists and wage-laborers -- corresponding to the three great forms of revenue, ground-rent, profit and wages, and the class struggle, an inevitable concomitant of their existence, as the actual consequence of the capitalist period." And according to an April 30, 1868 letter Marx wrote to Engels, "since those 3 items (wages, rent, profit (interest)) constitute the sources of income of the 3 classes of landowners, capitalists and wage laborers, we have the class struggle, as the conclusion in which the movement and disintegration of the whole shit resolves itself." So Marx had intended to discuss this, and his overall system for a "critique of political economy" ends with "world market and crisis," which each, despite the difference viewpoints stemming from their different dimensions, deal with a criticism of capitalist production itself, and a demonstration of its necessary collapse due to its internal contradictions. In his letter to Lasalle quoted earlier, Marx, after saying that "the work I am presently concerned with is a Critique of Economic Categories or, if you like, a critical exposé of the system of the bourgeois economy," he adds, "it is at once an exposé and, by the same token, a critique of the system," and this is no empty statement[5].

A: Let's move on to discuss the second main heading in this second volume, entitled "Economic Formal Determination."

B: The term "economic formal determination" is not used as much in Capital as in Marx's previous works, and could instead be seen as lurking in the shadows, so why was this given prominence in Lexikon as a separate heading?

Kuruma: The terms "economic formal determination" and "economic formal determinacy" are very noticeable in A Contribution and Grundrisse, whereas, as you note, they cannot be seen often in Capital. I think this stems from Marx trying to avoid such Hegelian sounding terms, and using alternative terminology, but I think that the term "economic formal determination" has great significance for understanding his fundamental view of the particularity of bourgeois political economy, and therefore for understanding the fundamental stance of his critique of economic categoriesc

B: "Formal determination" seems to be a rather cherished term among some Marxist scholars.

Kuruma: Yes, I have also come across such examples from time to time, but in most cases it is rather unclear how the term is being used, even if we read the surrounding context; or at least the term is not being used in the sense that Marx had employed it. Granted, there is no reason why a term has to be used in the same way it was used previously by someone else, but it does at least need to be used in a way that has significance for the person employing it, particularly in the case of a scholarly discussion. When talking about an aspect of Marx's theory, it is best to avoid using a term in an arbitrary way when Marx considered it to have important significance, because this will only invite misinterpretation and needless confusion.

Some time ago, in one of the undergraduate seminars I taught, some students often used the term "formal determination." But when I actually asked what this means, they had almost no idea at all. I reckon that they must have seen the term in something written by a popular author at the time, and had sought to use it without careful reflection. This reminds me of a passage in Faust, where an earnest student from the provinces asks: "But words must have ideas too behind them"; to which Mephistopheles responds: "Quite so! But just don't fret too much to no avail, because just when ideas fail, words will crop up."

B: So you sought in this heading to clear how Marx uses the term "economic formal determination."

Kuruma: Yes, that's right.

A: The main heading above, incidentally, is divided into three subheadings, and the meaning of each subheading should become clear to anyone who reads the text, so could you just provide a brief explanation of your intentions in creating each subheading?

Kuruma: The first subheading -- 47 "What Does Formal Determination Mean for Marx?" -- gathers together passages that seem useful in terms of becoming familiar with the general meaning of the term "economic formal determination" for Marx. But these passages alone are insufficient. This is because Marx thought that use-value itself does not indicate a social relation of production so it is not economic formal determinacy, and therefore is outside of the realm of consideration of political economy, but after reflecting on the fact that this is not invariably the case, he considered the degree to which it is outside or inside this realm of consideration; and there are various passages where he raises this question. And the second subheading 48 -- "To What Degree is Use-Value Outside of Political Economy and Formal Determinations, and to What Degree is it Inside?" -- consists of citations from these passages. This subheading clarifies the relation between use-value and economic formal determinations, and supplements the general concept of economic formal determination acquired in the first subheading with concrete content regarding it, while at the same time clarifying the role played by use-value within Marx's criticism of political economy and how it fundamentally differs from bourgeois political economy on this point, thereby deepening the understanding of the characteristics of the method of Marx's political economy compared to the method of bourgeois political economy, by becoming familiar with one of its concrete approaches. In terms of this, I particularly recommend looking at the last entry, [228], in this subheading. The final subheading -- 48 "Economists Lacked the Theoretical Sensibility to Grasp the Economic Formal Determination -- as is clear from its title, is made up of passages discussing the defect in the sensibilities of bourgeois economists regarding economic formal determinations. This defect was the inevitable outcome arising from their bias in terms of treating the relations of bourgeois production as being natural and supra-historical. That is, as long as the relations of bourgeois production are thought of as being natural and supra-historical , even if there is an interest in the content of these relations, there will naturally be no interest in the particular social formal determinations. Their defect regarding this point has the same cause as their defect in criticizing economic categories, as we just saw in Grundrisse (see subheading 45), and there is a close relation between both defects. The same thing also applies to the subheading 22 in the previous volume of Lexikon, entitled: "Ricardo and Other Economists Neglect the Qualitative Aspect of the Problem (and its Formal Aspect) -- An Inevitable Outcome of the Bourgeois Limitations of their Perspective." So the reader can read this passage as well by way of comparison.

I'd like to take this opportunity to say a word about the main heading "Economic Formal Determination" as a whole. In Grundrisse and A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, particularly when Marx discusses money, the term "formal determination" appears prominently. It is used in terms of "the formal determination of money qua measure of value," "qua means of circulation," or "qua money," or in terms of "the various formal determinations of money are..." But in Capital the term "formal determination" is for the most part replaced by the term "function." There is even the example of Marx crossing out "formal determination" in his own copy of A Contribution and replacing the term with "function." This is quite intriguing by itself, but in Lexikon these passages regarding the independent formal determinations of money have, except for a few exceptions, been left out. This was done because they are going to be included in the future volumes that deal with the topic of money, so I didn't want them to overlap.

A: Now let's move on to heading VIII. This third heading -- entitled "What is the Relation of the Theory of the Commodity and the Theory of Money to the Original Theory of Capital?" -- contains six subheadings. You are probably quite tired at this point, but could you briefly explain the reason for creating these particular subheadings?

Kuruma: Over a period of many years leading up to the present, many points have been raised regarding Capital, and these have become the seeds of debate. For example, the question of the "contradiction" between volume one and volume three of Capital, and the related question that was raised regarding the nature of the commodity discussed at the beginning of volume one in terms of whether it is a pre-capitalistic commodity or something abstracted from a capitalistic commodity -- and in the case of the latter, what is, or should be, abstracted out of the capitalistic commodity; the question of what it means in part one of Capital to set aside the process of production when analyzing the commodity form of the product and the metamorphosis and circulation of the commodity; the question of whether it is strange to use the term metamorphosis regarding the commodity because, in the case of the commodity, value is not the subject of the process as in the case of capital; etc. Of these questions, some of them are quite old while others have been raised recently, and some where raised in the direct form mentioned above while others were raised in the background to these other questions; at any rate, however, all of them come down to the question of the particular significance the relation between part one of Capital ("Commodities and Money") and the subsequent volume three has vis-a-vis Capital, which in turn comes down to the "dialectical composition" of Capital (see p. 335 in the first volume of Lexikon on the topic of money). It was based on this thinking that I included heading VIII on the relation of the theory of the commodity and the theory of money to the original theory of capital. This heading was then divided into six subheadings, but it was not the case that these subheadings had to be created for theoretical reasons. Rather, as I explained in the "Word from the Editor" for the insert in the first volume which covered the topic of competition, these subheadings were merely the result of putting my various note cards into order.

Kuruma: As for the final heading, entitled "Miscellaneous," it includes passages that are more or less related to the topic of method but do not fit easily into the other headings.

A: We have been talking for a long time and Professor Kuruma must be quite tired. I would like to thank everyone for participating today.

1. Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, chapter 6.

2. Ibid.

3. Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 3, chapter 13.

4. Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1, chapter 19.

5. The English translation in the International Publishers edition seems a bit off here. The German is: "Es ist zugleich Darstellung des Systems und durch die Darstellung Kritik desselben," and the Japanese translation of this quoted by Kuruma can itself be translated as: "It is a description of the system and at the same time, through this description, a critique of it."