T. A. Jackson

The British Empire

Date: 1922

Publisher: The Communist Party of Great Britain

Transcription/Markup: Brian Reid

Public Domain: Marxists Internet Archive (2007). You may freely copy, distribute, display and perform this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit “Marxists Internet Archive” as your source.

This Study is dedicated to the three Cousins—Nicholas, William, George, being respectively the Ex-Emperor of All the Russians, the Ex-Emperor of ALL the Germans and the King Emperor of many of the English, some of the Indians, and a very few of the Irish

I. What is the British Empire?

II. Its Rivals

III. The Empire and its Subject Nationalities

1. India

2. Egypt

3. Ireland

IV. The Empire and the Worker

1. White Workers and Niggers

The British Empire

Described by T. A. Jackson

This pamphlet first appeared in print as an article in THE COMMUNIST of July 2nd, 1921. In the intervening period nothing has happened to invalidate its conclusions. The Irish situation has developed a stage further; the Egyptian and Indian situations have become more tense, but that is all. The general development of this monstrous growth of British Imperialism remains the same, and the signs of decay are, not less, but more convincing.

___________________________________

I.

What is the British Empire?

THE term “Empire” denotes, firstly, the exercise of a superior and, if need be, an over-riding-control exercised by one nation or state over other states, nations, peoples or tribes. Secondly, it denotes the area and the population over which such power or domination is extended. Thus the “Roman Empire” was an extension of the over-rule and lordship of the City State of Rome to all the multitude of peoples, states, and tribes who occupied the Mediterranean Basin and the lands thereunto adjacent.

The British Empire is the exercise of the authority and legal right of the British Crown and Government over sundry territories situated in all parts of the globe, and over the various states, governments, peoples, nations, tribes, and settlers located therein

The extent of this Empire can be expressed either in terms of territory or in the number of its inhabitants. It comprises an area of approximately 13½ million square miles which is populated by some 460 millions of human beings. These are drawn from all the principal sub-divisions of the human race:—white, black, red and yellow, and (as its name indicates) the ultimate dominion over this vast mass is exercised in theory and practice solely by the British with their white colonial kinsmen. These number a little more than the odd 60 millions; so that on the most favourable view 400 millions of variously coloured peoples are subjected beneath the rule of 60 millions—mostly living at other ends of the earth.

This view, however, misrepresents the actual state of affairs completely. The overwhelming majority of the whites are congregated in a few main centres: 47 millions (approximately) in the British Islands, and the bulk of the remainder in Canada, Australia and South Africa. The greater part of the “coloured” races therefore are ruled in practice by the few thousands of white persons who form part of the official machinery of the British State.

The machinery is highly complex; so much so that an Imperial Conference of representatives of the chief self-governing Dominions with representatives of the Indian Government and of sundry sub-rulers favoured with British Imperial protection assembled recently in London to consult upon the co-ordination of the machine whose discordant and anomalous variety renders it unworkable under the strains economic and political which have developed in consequence of the war.

The Empire is constituted thus:—

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (and the Channel Islands)—at present a constitutional Monarchy—is the seat of Government and the constitutionally limited Crown thereof the fountain of authority. Then come the chief self-governing Dominions which have arisen from the emigration from Britain of British subjects who retaining their allegiance to the British State retained also their constitutional rights. From the progressive application of these latter has grown the fact and right of self-government under the more or less nominal control of the Home State. One of the problems of the Imperial Conference is to settle the limits and form of this control (if any), and the nature and extent of the reciprocal rights to which the Dominion shall be entitled. These Dominions are:—the Dominion of Canada, the Commonwealth of Australia, the Union of South Africa, and New Zealand. Newfoundland (with Labrador) is a self-governing Colony which has so far declined the option of inclusion in the Canadian Dominion.

In addition to these extensions of the British nation which are, or have been, in practice, all but independent democratic republics, are a number of areas held as conquests of the forces of the British Crown. Chief of these in population and economic importance is India. This is in reality the British Empire both in the sense that it comprises a number of separately organised states each subject as a whole to the British rule, and also in the technical sense that the “King” of England is also “Emperor” of India. India as a whole is governed by a Viceroy and a civil and military apparatus all acting under the nominal supervision of the British Cabinet effected through the Secretary of State for India. Outside of British India proper are a number of native states with their own civil service which yield tribute to Britain through its Indian Government, and accept the control thereof through duly appointed agents. There are in addition certain Indian States which accept British suzerainty in a more remote form.

On the whole there is, or was until recently, little pretence of consulting the wishes of any of the Indian people below the rank of ruling princes or wealthy and semi-Anglicised bankers. And these have a power which (like that of the mass of the population in Britain itself) is more nominal than real.

In addition to the self-governing Dominions, and the Indian Empire, there are under the British sway:—Crown Colonies, administered by civilian governors appointed by the British Crown and assisted by local

councils variously appointed; Territories administered by crown agents, or by chartered companies acting in the capacity of such; Possessions ruled by military or naval governors; Dependences administered by their native rulers under British protection and with British assistance in the matter of military force; Districts leased to the British Crown for a term of years (with a more or less tacit option of renewal on expiration); and, finally, Mandated Regions, i.e., areas over which the British Government or a Dominion exercises sway by virtue of the Versailles Peace Treaty.

These latter constitute a special refinement of the Imperial problem. Britain stands in an Imperial relation to Australia, but that Commonwealth in turn has Empire over Papua, New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago. New Zealand has a “mandate” for the West Samoan Archipelago and Togo land. The Union of South Africa one for what was German West Africa. Thus a possibility arises of divergence of views and interests between the Mother State and its offshoot Dominions accompanied by embarrassing problems of finance and military control.

There were thus urgent reasons for the Conference.

The most pressing problems before the Conference were economic. Difficulties have arisen partly from the commercial dislocation which is a direct consequence of the Versailles Peace Treaty—(a treaty which aimed at destroying entirely the industrial and commercial life of the Central Powers and gave no regard to the reactions of that destruction upon the economic life of the Allied countries)—partly also from the enormous increase of Imperial and Colonial State debts; and partly from the depreciation of the currency of Britain itself—with the disparity between that deflated paper currency and the gold currency of the various Dominions.

To solve these problems within the conditions of capitalist production, without creating greater problems still, will be impossible. For example:—To readjust production in such wise as to make the Empire a self-contained entity would involve the scrapping of many established industries and their replacement by those upon which Central Europe has hitherto specialised. This would involve scrapping the workers skilled in the abandoned industries and either adapting them to the new speciality or importing skilled workers ready trained from Central Europe. In the one case the British worker would lose his life-standard and status; in the other all chance of a livelihood. The building of new industries, too, would require a volume of credit which in the present condition of world finance is only accessible on ruinous terms. Credit could be mobilised if the huge war debts could be liquidated. To do this would require an enormously increased surplus of production over consumption, which can be attained only by a drastic reduction of the workers’ standard of living coincident with a proportionately greater increase of output. Such a reduction of the workers’ standard is impossible without drastic social strife. The continuance of such strife will check production and shorten credit its suppression will expand the indebtedness which it is imperative to reduce. The increase of output is impossible without abundance of cheap raw materials for which the existing dislocation provides no facilities. The workers might tolerate reduction of money-wages if there were an equivalent fall in the cost of living; but this to any serious extent would mean a loss of revenue alike to the Dominions and the Imperial State from the consequent fall of taxable prices, profits and incomes. This might be borne if the currency were deflated, but this again would entail a still greater volume of production in order that the debt incurred in inflated prices might be paid in goods priced at the deflated rate. It would mean paying a full sovereign in return for one worth only 6s. 8d. To equalise currency rates throughout the Empire would mean the extension of a dictatorship of banking experts over the whole. But even then exchanges would take place greatly to the disadvantage of the Dominions with a consequent falling off of trade and increasing domestic difficulty. To do nothing is to await collapse; to do anything is to risk revolt and revolution.

Broadly speaking, the problem may be summarised thus:—Capitalist individualism has been superseded by Capitalist Imperialism. The former created its own net-work of economic inter-relations regardless of race or frontier; being concerned only with its end—the realisation of surplus-value in a money form and its progressive conversion into privately-owned production capital. The latter seeks to readjust production and exchange upon the basis of the Empire as a whole. It is therefore forced to make drastic inroads into what have hitherto been regarded as the private rights of traders, manufacturers and speculators. At the same time it is an exploiting system aiming at a collective surplus value, which it seeks to realise in credit forms for division among its privileged property holding units. It is, it will be seen, driven increasingly to collectivist interference with the relics of capitalist individualism.

It is, none the less, an even more ruthless system of exploitation in that the exploited wage-workers, small producers, and peasantry lose all chance of gaining advantage from competitive divisions among the exploiting class. Its logical end is a system such as was described by H. G. Wells in his “When the Sleeper Awakes,” or even more vividly by Jack London in “The Iron Heel”—a system which divides society into fixed orders of privileged and servile; the privileged showing the advantages of socialised wealth and opportunity; the servile mass held by force into an inescapable hereditary bondage.

If this end is to be reached the British Capitalist Imperialists must be able to hold their own against rival Empires and other dangers from without, and also to crush out all resistance from within. In neither case have they an easy task.

II.

Its Rivals

THE British Empire having grown at haphazard and as an incidental outcome of the struggle of the British Bourgeoisie for mastery of such markets as were available from time to time, shows a complete absence of that systematic completeness which was a characteristic of the slave-holding Empires of Ancient or the Dynastic-Feudal Empires of Mediaeval Times. It differs in the same respect from the quasi-Feudal Militarist Empires of France, Austria, Russia, and Germany. Each of these was constructed with a set purpose of gaining wealth for the ruling-power in the State and securing its military preponderance over its neighbours.

In the case of the British Empire military considerations until recently have been secondary to commercial and industrial; and for this reason more than others it has emerged as the Capitalist Empire par excellence. Modern developments have simplified the problem. There are in the British Empire no antagonisms setting a ruling dynasty with a privileged aristocracy of birth in opposition to the manipulators of finance and the controllers of commerce and industrial production. These are in Britain and the chief Dominions the ruling class; the military caste, the bureacracy and the aristocracy being merely its sub-sections. Their elements are constantly interchanging and their class solidarity is intensified with every elevation of a successful Bourgeois to the peerage and every advancement of the wearer of an ancient title to a Board of Directors. As for the Dynasty—whatever chance there was of it manifesting hostility to the Bourgeoisie of their system was destroyed with the Imperial thrones of Russia, Austria and Germany.

It has been computed that in Britain one-eighth of the population own seven-eighths of the total wealth. A like proportion is probably true of the white populations in the Dominions; so that we may with safety conclude that this Empire is ruled by, or at any rate, in the interest of, some eight millions of small and large owners of capitalist property. [As this estimate includes children it will be well to remember that no more than three millions can take any sort of effective share in its control and at least half of these again are women. Probably the widest extent of the "democracy" which is supposed to be its feature does not include more than a few hundred thousand, and of these for technical and economic reasons, not more than one in a hundred have any real power. These again are grouped by their economic holdings and liable to pressure from the actual heads of their groups. These heads amounting to a few dozen are the real rulers of the Empire].

With Germany and Austria crushed, and France financially dependent upon them, the rulers of Britain have no rival Empire to fear at the Western End of Europe. Russia has ceased to be an Empire and any problem it may present falls into a different category.

There remain three States of great population and immense potentiality either of which might conceivably serve as a barrier between the British Bourgeoisie and complete World Mastery. These are China, Japan, and the United States of America.

China, with an immense population and a soil of unknown possibilities, is too weak as a State and too torn by internal divisions to constitute any immediate menace. It forms a factor in the problem chiefly in the indirect sense that in the hands of either Soviet Russia, Imperial Japan, or the Plutocratic U.S.A., it might become of decisive importance in any World Conflict.

Has the British Empire anything to fear from either Japan or the U.S.A.?

Superficially it would seem that no such thing was likely. They were all Allies together against the Central Powers; there is, and has been, a strong popular sentiment in favour of a pacific understanding with the U.S.A.; and this sentiment is reinforced by the geographical relation in which Canada stands, and the financial relation of indebtedness to the Republic in which the war has placed the British Empire.

With Japan, Britain has had a Treaty of Alliance which has now lapsed. There is no popular wish for conflict with Japan, and (what is much more important) no immediate desire or occasion for quarrel on the part of the British ruling class itself.

But, as we have had only too much reason to know material and economic causes play a much more potent part in determining the course of Capitalist Empires than any desire to avoid trouble on the part of its ruling class.

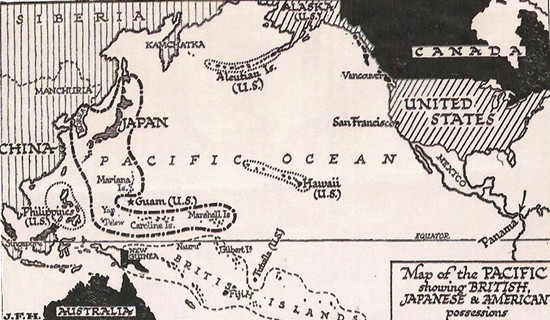

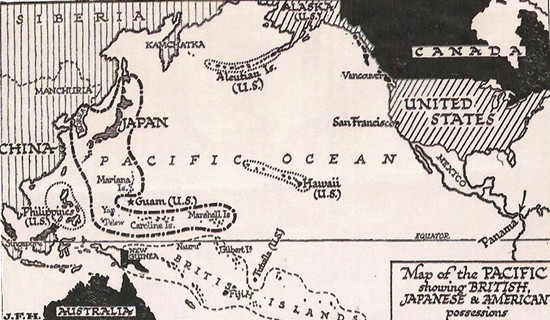

An examination of the map will reveal the possibility of such a collision between rival interests as would make the outbreak of 1914 almost trifling by comparison.

Surrounding the vast expanse of ocean are the sea-fronts of all the three Empires in question, with in addition those of China, Russia, Mexico, some Central American States and Chili.

Japan, a group of islands, lying towards the coast of Asia in the northern half of the Pacific, is in a position to dominate most of the coast of China, and to impede communication with Asiatic Russia.

The northern exit from the Pacific is (from its Arctic latitude) of no importance as a trade route and is controllable either from the Russian port of Vladivostok or more efficiently from the United States territory of Alaska. It is in any case the road to nowhere.

The entrances into the Pacific are either from the Atlantic around Cape Horn—a route dominated by the British possession of the Falkland Islands; from South Africa around the Southern Coast of Australia—a round-about route completely dominated by British Dominions; from the Indian Ocean through the Malacca States—a passage completely at the mercy of the British naval station and possession Singapore; and finally and chiefly, so far as the Atlantic trade is concerned, through the Panama Canal—completely under U.S.A. control.

Thus Japan has a highly favourable situation in China—an advantage which it has pressed to the full both in its conquest of Corea and by following up its acquirement (under the Versailles Peace Treaty) of what had been the German territory in Kio Chau and Shantung with the imposition of a commercial treaty with China—but is debarred from exit from the Pacific except with the good will of either Britain or the United States.

Thus Japan has a highly favourable situation in China—an advantage which it has pressed to the full both in its conquest of Corea and by following up its acquirement (under the Versailles Peace Treaty) of what had been the German territory in Kio Chau and Shantung with the imposition of a commercial treaty with China—but is debarred from exit from the Pacific except with the good will of either Britain or the United States.

Confined thus within the Pacific the Japanese Empire must expand, if at all, either at the expense of Russia, China, Australia, or the American continent. China, while of immense commercial value, is already crowded. The Pacific end of Asiatic Russia has been leased to an American syndicate. Australia has for long held fast to the policy of a White Australia, and the United States has not only adopted a policy of restraining Japanese immigration but is also jealous of any commercial invasion of the American Continent.

It must be remembered in this connection that the Capitalist system of production is one that creates the problem of a surplus population in an acute form both by its creation of a property-less proletariat which is rendered, in an ever-increasing proportion, superabundant for the needs of its labour market; and by its production of a class of educated persons of cultivated tastes without any means for their gratification at home.

For both reasons there exists a need for emigration from Japan, a need emphasised by the growth in spite of ruthless repression, of a Communist and Labour movement in Japan itself and a Nationalist boycott of things Japanese in Korea.

In addition to the need for colonisable areas as a safety valve is that for a control of the sources of raw materials for its chief industries silk—weaving, cotton weaving and steel production for home consumption—and for markets for its produce. Its cotton is mainly imported raw from the U.S.A., and in the manufactured state is sold in competition with the products of Lancashire and New England. The possibility of enlarged cotton cultivation and manufacture in China gives Japan an interest in its control:—similar possibilities in India, Mesopotamia and Egypt give occasion for either rivalry or an understanding with the British Empire; while the Pacific Islands are of unknown importance in this connection.

China is its rival also in the production of raw and manufactured silk, and the possibility of inter-dependence in this industry is an added motive for the exercise of Japanese domination. Here again the British Possessions—India, Burma, the Malay States, Northern Australia, and the Pacific Islands—are rivals actual or potential for the produce and marketing alike of raw material and manufactured product; and here too is rivalry with the

U.S.A.

From the United States Japan at present derives quantities of metal products and machinery, but it is an ambition of the Japanese Bourgeoisie to free themselves from dependence upon their rivals in this product. Great endeavours have been made to build up a Japanese steel industry—and there are possibilities of collision here likewise.

In general, there are ample reasons for the desire of the Japanese Bourgeoisie to gain a control over the development of China, to influence that of India, Burma, and the Malay States, to gain a footing in Northern Australia and in Southern California, and to possess as many as possible of the Islands of the Pacific.

For military and naval reasons the rulers of the British Empire desire to stand in the relation of Allies to Japan. Its commercial interest in, and proximity to, their Indian and Eastern Empire makes it impossible for them to be indifferent to, and the war has left them in no position to be aggressive against, any strong naval power.

The United States for its part has long foreseen the possibilities of a commercial future for the Pacific, its islands, and its coastal lands. In 1898 it annexed the Hawaian Islands, which lie in the centre of the Pacific. It possesses in Honolulu a harbour and dock suitable for the largest warships. In 1899 it captured from Spain the Philippine Islands, which lie at the point of inter- section of the routes from Singapore to Japan, and between Hong Kong and Australia. Also captured from Spain was the Island of Guam, a wireless and cable station, on the route from the Philippines to Honolulu. Finally the Panama Canal, by its immense shortening of the sea-route from the North Atlantic to the North Pacific brought the whole of the Eastern States of the Union (with their raw cotton, food-stuffs, textiles, metal and machinery products) into competitive reach of the Pacific—San Francisco continuing to serve a similar purpose for the Western States. The Canal too has the immense naval advantage of rendering it unnecessary for the U.S.A. to keep a separate fleet for both Atlantic and Pacific.

The issues have been drawn more tightly by the Versailles Mandate, which gave to Japan all the ex-German islands north of the Equator and to Britain and its Dominions, all south of that line. Among the islands thus transferred to Japan was Yap (South of Guam)—much to the indignation of U.S.A. cable interests.

Finally from the point of view of possible complications may be noted the fact that Chili (a Republic credited with naval ambitions) is disposed to be friendly to Japan in plain contempt of the U.S.A. and its Monroe Doctrine.

Before 1914 British statesmen were wont to point to the German menace as a reason for extending their naval armaments. That menace is finally disposed of. But to the dead menace its heir succeeds. The Imperial Conference concerned itself perforce with the naval problem in the Pacific. Japan and the U.S.A. have each in hand an extensive ship-building programme, with the consequence that the British Empire must follow suit or sink to the third rank in the Pacific. If it decides to join the competition of armaments there will have to be decided the delicate problem of how the cost is to be divided between the Mother State and the various Dominions, with the further problem of degree and form of control.

In this connection the most important fact is the apparently immovable objection of Australia and New Zealand even to contemplate assisting Japan in a war against the United States—an objection which is shared in different degrees by Canada and South Africa.

For its part the U.S.A. has, it would seem, little or no concern for the domestic emotions of the British Empire beyond the natural interest of a creditor in his debtor’s dilemma.

III.

The Empire and its Subject Nationalities

WE have seen from the foregoing how the complex nature of the Empire finds expression in divergent reactions to the possible antagonism of Japan and the U.S.A. This is all the more embarrassing from its contrast with the common dependence of all parts of the Imperial system upon sea-borne traffic. When we pass from the self-governing Dominions to the more populous and less independent portions, where the whites are few and the resources vast, the problem changes frankly into one of dictatorship.

Every part of the Empire has its problem of economic conflict between exploiting upper and exploited lower classes, and for a majority of its 460 millions this is further complicated by differences of race and nationality.

If the Empire is to be called upon to face with unanimity a conquering onslaught from either of its Imperialistic rivals these conflicts must be abolished, either by conciliation or coercion. To decide how far this is possible we must consider somewhat in detail the problems (1) of subject Nationalities; (2) of exploited races; (3) of the proletariat generally.

India

The area under the direct supervision of the Government of India has a population of 316 millions. To this must be added Ceylon (which is separately governed) with a population of 4½ millions. It is ethnographically divided into various races and innumerable sub-races, each with separate dialects, and these are further divided into a large number of native states, great and small, grouped for administrative purposes into provinces. The division of this immense population is still further complicated by the religious divisions—Hindu, Mohammedan, Sikh, etc., with the added complication of caste.

Economically India is an agricultural land in which a transition to modern manufacture has commenced. Seventy-five per cent, of its vast population are engaged upon agricultural production, which is, for the most part, still carried on by the methods of petty-culture. Of these again approximately one half still hold and work their land in the traditional “consanguine collectivism” of the village communitiy. The other half hold by a species of bastard-feudal tenure.

The coming of British rule has meant for them a simultaneous stereotyping of inherited social forms and traditional legal relations with the discordant and disruptive addition of taxation enforced in cash payments. This compulsory accommodation to the vicissitudes of the commodity market has at first imperceptibly then with ever accelerating violence, revolutionised the old patch-work of local isolations and divisions into an aggregating national unity which it is now the prime anxiety of the British Rulers to either neutralise or divert into inocuous channels.

The first establishment of the old East India Company over a wide stretch of what is now the Indian Empire, was not achieved without a struggle against their French rivals. It was successful as the Roman Empire had been successful by acting through the medium of the established rulers of the various territories and profiting from their mutual jealousies and rivalries. The effect of its rule was to recall as puppets princes whom normal development might have abolished and to give the backing of European military might to institutions that were fast lapsing into decay. It bribed these rulers into quiescence by its imported luxuries, and by its superior efficiency in collecting the revenue and coercing resistance.

The effects of its rule became apparent in the Sepoy Rising in 1857, which ail-but abolished British Dominion in India. The rising, however serious for the British, was the work of a section only of the military assisted by a few discontented princes and was, but in a prophetic sense, indicative of the possibility of Indian National feeling. With the suppression of that revolt the East India Company’s powers ceased and India passed wholly under the control of the British Crown.

The progress of British Rule with the division of the country into provinces each with its Governor and his Executive Council of Officers to which was later added a Legislative Council (the members of which were at first all nominated and all British) gave the first direction for Nationalist agitation.

The class which would, but for the presence of the British, have occupied places of authority in the government of their respective states, were placated with the offer of positions in the British governing system. The introduction of Western conceptions of law and police created the need for a class of legal and secretarial functionaries and Western education was offered to such as were financially or from favour able to take advantage therefrom. There was thus created out of the debris of the displaced social order an “educated” middle class in addition to a proletariat of household and body servants and the class of shop-keepers, dealers, and money-lenders who were the other by-products of this regime.

From the “educated” or Westernised class came the first vocal expression of Nationalist protest against the methods of British rule—although as early as 1877 there arose from more purely native sources a movement for the boycott of imported merchandise which, however, remained ineffective until quite recently.

The “Educated” movement took (in 1885) the form of an Indian National Congress, which was attended and made into a permanent institution by representatives of the educated class from various parts of India—chiefly Bengal. It aimed at concentrating Indian National opinion upon an agitation for constitutional reform and was designed, as an institution, to become the “germ of a native parliament.” It was, in short, little else than a Hindu variation played on the old tune of “Liberal Democracy” and like its prototype presupposed a proletariat or a peasantry with a Bourgeoisie being “Liberal” to itself at their expense.

The improvement in the means of transit, and in native education (slight as the latter was and is) had its reflex in a revived enthusiasm for Indian culture and ideas. This in turn found expression in a religious revival aiming at a purer form of Hinduism and both together brought the Nationalist movement and the upper strata of the general population into closer touch.

The defeat of Russia by Japan and simultaneously the partition of Bengal (an unsuccessful administrative experiment of Lord Curzon’s abandoned in 1912) brought the Nationalist movement into its second phase. An anti-Partition Boycott was approved by the National Congress, and the Swadeshi movement (the general boycott of foreign goods referred to above) became popular and widespread. Secret revolutionary organisations became known and active, and the Congress developed a Right and Left Wing. The conflict between the Moderates and Extremists caused the 1906 Congress to break up in disorder. The Extremists, led by Tilak, attempted to hold a separate Congress in 1908, but were prevented by the authorities. Administrative Reforms were introduced by the Government, which were approved by the Moderates, although they were transparently designed to be an effective block against further democratisation of the Constitution. Coupled with concessions to the Moderates was a policy of suppression directed against the Extremists.

Tilak, the Extremist leader, was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment for certain newspaper articles, and his sentence was only one among thousands of imprisonments, transportations, and deportations which have continued until now.

In 1910 a Press Act was introduced to control the Press and (according to the Press Association of India) over 350 presses and 300 newspapers have been penalised under the Act. £40,000 have been demanded in securities and over 500 publications have been proscribed. In the Andaman Islands—the Siberia of India—many editors and writers are undergoing long-term or life sentences.

The repression, however, as is usual, failed to effect the end desired. Social developments and economic crises—particularly periodical famine—re-created the agitation all the more because its expression was prohibited. It reached and eventually included in its scope those whom the British Government had thought to be immune—the Muslims.

It has been a traditional policy with the British Government to foster division between the Hindu and the Mahometan. It is for example a popular myth with reactionary Anglo-Indians that the two goats—black and white—periodically sacrificed at Indian village ceremonials, typify the Mahometan and British races respectively. That the myth is baseless no student of comparative religion needs to be told. That it is told and believed by the teller, throws a flood of light into the recesses of the official mind.

Despite religious distinctions and Government policy the Muslim community have been drawn into the current of Nationalist agitation. In 1906 an All-India Muslim League was founded with the intent to create a counter-poise against the Political Nationalist movement, which was as we have noted primarily a Hindu movement. Until 1913 the Muslim League made a parade of its loyalism and held aloof from Nationalist politics. But the policy of bribing the Moderate Nationalists with Government appointments created jealousy in the minds of the more reactionary Muslims, while the pressure of social development worked upon those of the more progressive. In 1913 the Muslim League added to its objects “the attainment of the system of self-government suitable to India,” and in 1916, under the pressure of the war, and the conflict between the British and Turkish Empires, the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress arrived at a compact of unity.

This event, which closed the second phase in the development of Indian Nationalism, was facilitated by the propaganda of Mrs. Besant and her Home Rule for India League; although the essential Moderatism of Mrs. Besant soon caused her to be left behind and repudiated by the Indian National Congress.

In 1916 that Congress, which had been dominated by the Moderates, adopted for the first time a full Home-Rule programme. Moderates and Extremists combined to demand with the agreement and support of the Muslim League, that India should “cease to be a dependency and be raised to the status of a self-governing State as an equal partner with equal rights and responsibilities as an independent unit of the Empire.”

Although this demand is in no sense a revolutionary one, and although it accepts as permanent the right of Britain to Imperial Domination over India—which is, in practice, all that “equal responsibility” within the Empire means—it was sufficiently portentous, coming when it did, to compel the British rulers to execute one of their customary manœuvres of Reform.

In December, 1917, the British Government announced its intention to concede far-reaching reforms in conformity with the principle of ultimate self-determination. This concession, which over-joyed the Moderates was, in accordance with precedent, accompanied by ferocious measures of repression aimed at the Political Extremists and the “Underground” Revolutionists.

The Government of India Act (1919) was preceded by the Rowlatt Act (of March, 1918) an Indian Emergency Powers Act, which made legal “punitive and preventive measures,” extended the power of judges to summarily convict in cases of “anarchical and revolutionary crime”; gave local governments the power to order entrance into “bond of good behaviour”; authorised arrest without warrant, and confinement under specified conditions; and also the search of any, place which “has been, is being, or is about to be” used by a person so arrested; applied this Act to persons already convicted; provided that “no order under this Act shall be called in question in any Court”; and added these powers to those “already exercisable under other enactments.”

This precipitated a crisis in Indian Nationalism. The vast majority refused any of the proposed reforms while they were accompanied by the Rowlatt Act, and a small fraction of Moderates with Mrs. Besant seceded from the Congress to form a “National Liberal Congress.” The Extremist Majority thus freed from the Moderate drag passed more than ever into touch with genuine native sentiment, which at this time began to be dominated by a new personality in Gandhi.

In opposition to the Rowlatt Act he initiated a policy of “non-co-operation”—a policy which has curious resemblances to that of Sinn Fein as first formulated by Arthur Griffith. The theory of this policy is quite simple. “British rule is impossible without the passive or active co-operation of Indians. Let us refuse to co-operate.” First of all “Swadeshi”—the boycott of all imported products; add to that the boycott of all the British factories established in India, the boycott of the elections to these bogus Legislative Councils, the boycott of British controlled schools, of their courts, of their ceremonial occasions; the passive disobedience of such of their orders and proclamations as contravene the national right, the abandonment by loyal Nationalists of all titles, honours, and appointments conferred by the British ruler—in a word, by all means short of armed conflict and personal violence, to break connection with the “Satanic” rule, culture, and patronage of Britain.

The movement was well-timed. A wave of prosperity induced by the war-created demand for Indian products coupled with the rise of the purchasing power of the currency (a relative expression of the depreciation of the British purchasing medium) had spent its force. Then followed a depression and a sudden drop in the purchasing power of the currency. The cost of the necessaries of life remained high. European demand for Indian products fell almost to zero; and to all other causes of stagnation were added that of the breakdown of the rail-ways in consequence of war-strain and neglect.

It must be remembered that although only some 5 per cent, of the Indian population forms an industrial proletariat, this small percentage is in absolute numbers a considerable mass. Eight millions, for example, are engaged in textile manufacture and the stagnation of industry produced frightful suffering among a class who are, at the best of times, probably the worst-treated workers in the world.

Labour conditions are disgraceful. Wages are almost unbelievably low. The Report of the Indian Commission cites as specimen wages in Bombay cotton factories (June, 1918) from 4s. 2½d. to 15s. 8d. per week; in Calcutta jute mills from 3s. to 10s. per week; in Bengal coal mines 7½d. per day. The hours of labour are fixed by the Factory Act of 1911 at 12 per day for men, 11 for women, and six for children, with a 30 minutes’ break during the day for meals. Sanitary provisions are barely existent. In addition, housing facilities are all but unthought of—the workers having to walk miles to and from their work. In Bombay three-quarters of a million workers are tenanted in one-roomed dwellings.

Notwithstanding the inevitable loss of efficiency from under feeding, debility and disease, profits (in consequence of the pleasant theory that the Indian can live on next to nothing) are magnificent. Of the Bombay cotton mills (in 1919) three paid 40 per cent.; two paid 50 per cent., and one each 56, 70, 80, 100, and 120 per cent. Three jute companies in 1918, paid a dividend of 20 per cent.

It is not surprising that, faced with unemployment and high prices after a prosperity such as this, that strikes sudden and huge began to be a feature of Indian life and to form part of the equipment of the non-co-operation movement.

The events at Amritsar assisted to establish the popularity of the new Nationalist movement. A meeting called to protest against the Rowlatt Acts was forbidden by the military governor. In accordance with the principle of passive resistance, it was held notwithstanding, and the British General Dyer, frantic at this “defiance” to his authority, ordered the troops to open fire. There was only one exit from the place in which the meeting was held and at this the troops were stationed. When their ammunition was exhausted the troops withdrew, leaving behind them several hundreds of killed and wounded natives.

Horror at this outrage roused and embittered sections of Indian feeling which had till them remained aloof from the National agitation. The Congress in 1920 formally adopted the policy of non-co-operation. The new constitution granted by the Government of India Act has been formally inaugurated and elections thereunder held. Of this Constitution it suffices to say that its admirer, Sir Valentine Chirol, can only claim that it is nearly as “democratic” as was the British Parliament before the Reform Bill of 1832. He concedes that “not only has economic and social unrest never been more widespread, but for the first time all the heterogeneous forces to whom . . . the British connection is equally hateful, have found a magnetic leader who knows how to resolve all their dissonances into a harmony of progressively passive and spiritual insurgence against a “Satanic” government and a “Satanic civilisation.” He recognises that this propaganda is aimed not at mere Home Rule within the Empire but at “the severance of all connection with it and with the civilisation for which it stands.” He notes, too, how the economic aftermath of the war has helped to emphasise and prepare the ground for this “fiery propaganda,” and in that connection says that native merchants who had rashly relied on what they thought (mistakenly it appears!) was a Government promise to stabilise the rupee at 2s. gold, and in that belief had ordered goods in England at top prices, are now faced with the fall of the rupee to 1s. 4d., and consequently cannot or will not take delivery. “Manchester piece goods alone (he says) to the value of millions sterling lie in harbour or in the docks at Bombay for which the Indian importers refuse to take delivery.”

He laments that (in the absence of “responsible labour organisations”) labour grievances are championed by nationalist agitators, and that the undoubted evils of landlordism (“evils which have been allowed to survive since pre-British times”) have given rise to “serious agrarian troubles” and a general spirit of revolt.

The last word can be left to the Indian Government. In introducing the Budget to the new Legislative Assembly they had to announce a deficit of 18 millions. This they explained was due to an enormous military expenditure, absorbing half the revenue of the country, necessitated by “the constant menace of grave trouble from the N.W. Frontier, and Afghanistan, and a Bolshevised Central Asia beyond.”

In Burma a nationalist agitation did not appear until 1920. It is conducted at present chiefly by the Young Men’s Buddhist Association, which after a vigorous protest against the Government’s Excise Policy and in favour of Prohibition, passed on at a joint conference with Allied Associations to decide upon a boycott of the elections for the All-Indian Council of State and the Legislative Assembly. Their complaint was chiefly against the composition of the electorate for the Legislative Assembly, which is made up to the number of about one hundred out of presidents and vice-presidents of municipal committees and of elected representatives to those committees. These are all thought worthy of a vote out of a population of 12,000,000. When a Burman was elected to the Council of State (by the European vote) the Buddhist Associations retorted by a social boycott of him.

Strikes of rice-mill coolies, river-workers, and Government clerks, with a boycott of imported products, are symptomatic of the influence upon Burma of the General Indian movement. Conflict is likely to arise over the Government’s intention to encourage the development by foreign capital of rubber, sugar, cotton and cocoanut plantations. It is feared that these concessions will be made at the expense of the popular rights to grazing land, fuel, and opportunity for extension of cultivation.

Egypt

The case of Egypt is simpler.

The British occupied Egypt in 1882 in order to quell a Nationalist rising against Turkish over-lordship and Franco-British financial control: The British ownership of a majority of the shares in the Suez Canal Company and the importance of that Canal to its commerce and intercourse provided ample excuse. Mr. Gladstone's government disclaimed all intention of establishing a protectorate and this disclaimer (addressed to the Powers on January 3rd, 1883) was worded thus:—

“Although for the present a British force remains in Egypt for the preservation of public tranquility, Her Majesty’s Government are desirous of withdrawing it as soon as the state of the country and the organisation of proper means for the maintenance of the Khedive’s authority will admit of it. . . . ”

More than sixty responsible ministers have repeated since then this pledge that the occupation was only temporary yet the British position was steadily consolidated.

Persistent Nationalist agitation was met in 1913 by the formation of a “legislative” Assembly whose powers were consultative only. It met only once—the coming of the war in 1914 providing a reason for its indefinite adjournment.

The war placed Egypt in a most anomalous position. It was still nominally a province of Turkey, with which Britain was at war, and was therefore also “at war” with Britain. The British acted promptly. The Khedive, who showed signs of loyalty to Turkey, was deposed, a puppet Sultan set up in his place, and Egypt was declared a British Protectorate. A great care was shown at this point to avoid arousing Egyptian Nationalist hostility. They were assured that if they did nothing to impede the British prosecution of the war they might count on the concession of self-government as soon as it terminated. This assurance was accepted by the Egyptian Nationalists, and nothing in fact was done to hinder the British or aid the Turks—even when a military attack upon the Suez Canal was imminent.

The British for their part imposed a particularly rigorous censorship of letters, telegrams, newspapers and the Press and further, in direct contradiction to their pledge that the Egyptians themselves should not be involved in the war, a covert conscription was adopted to provide men for a Labour Corps. The anger excited by this was intensified by drastic commandeering of food, transport animals, fodder and equipment. This had the effect of rousing the hostility of the peasant mass of the population, who had so far stood outside the ordinary Nationalist agitation.

The population of Egypt is approximately 13 millions. Foreigners to Egypt—Greeks, Italians, British, and French—number, all told, some 140,000. Most of the business, banking, and industrial enterprises are in the hands of these “foreigners” who by virtue of sundry “Capitulations” wrung by their national governments at various times from Turkey, are highly favoured legally and economically.

Sixty-two per cent, of the native population is engaged in agriculture, one-quarter of them being small-holders and the rest labourers. The microscopic minority of foreigners own one-eighth of the cultivated land—the chief crop being cotton, while sugar, rice, cereals, pulses, and vegetables are important. The industries are sugar refining, textile fabrics and yarns. There are also valuable salt and soda works.

It is estimated that 88 per cent, of the native population are illiterate and the higher education is exclusively Europeanised. From the “Educated” middle class aspirants to government posts and commercial advancement came such Nationalists as there was until the war; the agriculturalist being in the main either too busy or too wretched to occupy himself with such matters.

The war measures above referred to had the effect of rousing the labouring mass into action of a Nationalist character. When the Armistice came, and it was found that, despite promises, the British merely strengthened the martial law and intensified the censorship, feeling ran high. Prices were ruinous, disease was rife. The Ministry resigned and as nobody would take its place, the country was left without legal government. Nationalist delegates, trusting to the words of President Wilson, sought to reach Pans and put before him their claims as a “small nation” to the “right of self-determination.” Passports were refused them and they were deported and interned in Malta. A few days later they were released and allowed to proceed to Paris, but in the meantime their treatment had (March, 1919) roused Nationalist feeling to a frenzy which culminated in a spontaneous rising of the peasantry and proletariat. Several obnoxious British officials were murdered, but the rising as a whole was too ill-equipped and too little concerted to succeed. The native police refused to act against the insurgents, who were accordingly suppressed with ruthless barbarity by the British Military Authorities, to which sections of the British Army added special abominations on their own initiative. The movement for “non-co-operation” spread. Many holding official posts resigned, and mass-strikes, the first known in Egypt, added to the national protest. So persistent were the students’ strikes that martial law was introduced into the schools.

The seriousness of the revolt induced the British Government to release the Nationalist delegation from their internment. They proceeded to Paris, but during a whole year failed to secure a hearing either from President Wilson, the Peace Conference, or any of the Allied statesmen. They were no longer satisfied with “Dominion Home Rule,” but asked for complete independence.

The British Government (in May, 1919) announced that Lord Milner would proceed to Egypt to prepare a constitution under the British Protectorate. The announcement was received with derision, and the Nationalist movement commenced preparations to boycott the Mission. Lord Milner remained in Egypt for three months, but so complete was the boycott that he and his colleagues returned without being able to consult a single representative Egyptian. On his return to London he Appealed to Zagloul, the chief of the deported delegation. After prolonged discussions, the Milner Mission drew up in concert with them a report, recommending the withdrawal of the British Protectorate, the acknowledgment of the independence of Egypt, and the establishment of certain safeguards for British interest civil and military in the Suez Canal. The question of the Soudan was left over for later treatment.

The British Government declined to endorse the Milner report, and attempted to persevere with the idea of “Dominion Home Rule.” The Nationalists persevered with their boycott, even though a sort of Egyptian Ministry has been set up and a constitution of a kind is to be granted.

Strikes and demonstrations still occur, ending frequently in collisions with the military. Killings and floggings were taking place in Cairo and Alexandria when the British at home were celebrating “Empire Day” in 1921.

Ireland

Nearer home there is the problem of Ireland, a problem grave not only from the military importance of its geographical position, but from the political importance of the millions of Irish blood who dispersed through the Dominions and the U.S.A. form a factor that must enter into the calculations of every would-be “democratic” administrator.

The present situation is that an “unofficial” but real state of war exists between the British Empire and the Republic which has been set up by the population of all Ireland outside of Orange Ulster with virtual unanimity. The authority of the British Empire extends to its armed forces. The authority of the Irish Republic is, outside of Ulster and Trinity College, accepted everywhere else. The armed forces of the contending authorities are in constant collision; Ireland having been for two years a theatre for a hideous drama of raid, and counter-raid, reprisal and counter-reprisal. As in India and Egypt, an attempt has been made by the British Government to secure peace by the concession of a species of self-government “within the Empire.”

* * * * *

The first invasion of Ireland from England took place little more than a century after the Norman invasion of England itself. From that time (1186) forward until now—in one form or another—a struggle has been waged against the invader.

Repeatedly Irishmen have risen in arms; ruthlessly each rising has been suppressed; only to break out again with redoubled violence after the lapse of at most a few generations. The form and the consciousness involved has varied all the way from the earlier risings of clans under their chieftain-princes down to the popular republican struggle of Sinn Fein; but the objective all the time has been the same—the recapture of Ireland front the invader from England.

For a time (from 1870 to 1914) it seemed that the national aspirations had become narrowed into the limited demand for a local legislature. This, after a fashion, was what the Imperial authorities sought to impose upon Ireland in the grotesque form of two Parliaments (one each for Ulster and the Rest of Ireland) with a co-ordinating Parliament—like them, in two chambers. It is instructive to note that what was treated as a seditious proposal in 1870 was in 1921 thrust upon the unwilling Irish as a masterly constitutional experiment.

The Dublin rising of 1916 was the point of departure for the present phase of the Irish National struggle. It was in one sense merely a return to the normal trend of popular political idealism, which had been interrupted by the Parnellite Parliamentarian episode, whose ghost lingered on the stage till 1914. The Rising in this sense formed but the latest link of a chain which reaches back through the Fenians (1867), Young Ireland (1848), Robert Emmett (1803) and Wolfe Tone, the United Irishmen and the Wexford peasantry (1798). It resembles them, too, in that in each case the driving force behind the outbreak was the embittered class- feeling of a subject class, more or less moulded and led by idealist intellectuals. It differs from them in the important respect that in 1916 this subject class was an organised and militant section of the proletariat. Previous efforts had been predominantly those of the peasantry.

Connecting with this proletarian backing was an element of idealist Communism distinctly to be traced in the writings of its literary and political head, Patrick Pearse, and in the Marxist affiliations of its miliary chief, James Connolly.

The Parnellite Parliamentary struggle, backed as it was by a policy of militant agrarian “direct-action,” organised by the Land League, had extorted from the British Government a series of Land Acts (1881-1903), whose total effect was to emancipate the peasantry from a worse-than-mediaeval servile tenure, and make possible a revival of prosperity for Irish agriculture. It had been hoped that these Acts would reconcile the peasantry to British domination. Their effect was the reverse.

With freedom from the more galling and obvious exactions of landlordism, came freedom from the servility and meanness of outlook which were its outcome. There were fewer outreaks of sullen malice and secret passion, and in their place arose a broad and inspiring perseverance towards the goal of independence.

From 1896 to 1912 were the formative years of the Neo-National revival; from 1912 to 1916 its birth-process; from 1916 to date its novitiate into the struggle for mastery.

The main factors in the first period were (1) a literary and language revival, conducted by the Gaelic League; (2) an historical revival of Republican idealism, pioneered by various literary societies and ably seized upon by James Connolly for his propaganda purposes; (3) Connolly and Larkin’s propaganda of militant proletarian industrialism and (4) the Sinn Fein Neo-Nationalist movement.

The two movements which aroused the greatest attention were the Gaelic League and Sinn Fein, both pacifist, and the Gaelic League not even political. The others, although in ultimate theory militant, seemed at first to make little headway. Sinn Fein, at first a mere literary propaganda, built upon concepts that we have learned to call those of “non-co-operation.” In Sinn Fein language, they were those of “national self-reliance,” and they proposed, firstly, the systematic patronage of Irish products in preference to any foreign alternative; secondly, the concerted use of political organisation to aid the development of Irish industry and commerce; thirdly, the abstinence to the British State; and, fourthly, the abstention of elected persons from Westminster—they instead of “wasting their time” and “compromising the national honour” in that way, being constituted a National Board of Control to supervise this industrial and commercial development and to make openings for it by the appointment of a consular service wherever practicable.

Although Sinn Fein attracted a good deal of notice and in its industrial policy a good deal of approval, especially from the sphere of influence of the Gaelic League, it made little apparent headway against the Parnellite tradition, which had not then spent its force.

The Home Rule Bill of 1910, and the constitutional struggle in the British Parliament over the Budget and the Parliament Act, not only absorbed Irish attention, but in the outcome provided the occasion for a new orientation of opinion.

The organisation of the Ulster Volunteers and their equipment with arms imported from Germany in order to resist Home Rule with violence, gave a new birth to the traditional idea of a militant struggle for Irish Independence. Connolly, in the throes of a labour struggle against the sweating bosses of Dublin (in the course of which collisions with the police had become chronic) was glad to seize the chance and followed suit with the formation of a Citizen Guard of his proletarian stalwarts. The Republican Revolutionaries were glad to seize the opportunity likewise; and, to the secret chagrin of the pure parliamentarians, the Nationalist Volunteers sprang into being. At first the Parliamentary Party was able to keep some sort of control over this force, but the outbreak of war and John Redmond’s somewhat theatrical offer of the services of all Ireland to the British Government in gratitude for the Home Rule which (as time was to show) he had only gained on paper, proved the breaking strain. The militant majority broke away from Redmondite leading strings and a revolutionary

left wing of these again joined with Connolly’s Citizen Army to make the Rising of 1916. It must be confessed that the British Government pursued a policy which could not have been better designed had its purpose been to provoke such a Rising upon an even greater scale.

Everything possible was done to patronise the Ulster Volunteers and their leaders; everything possible to discourage and even insult the Nationalist War emergency was made a pretext for the suppression of militant journals and in every way it seemed to be clear that the British Empire was, even in its extremity, resolved upon manifesting at whatever cost its implacable hatred of Irish aspirations for self-determination. It was inevitable that the aggravations of British policy should find vent in a violent explosion.

With the execution of the leaders of Easter Week commences the latest phase of Irish National struggling. Its beginning was the study of the writings of Pearse, Connolly, and others of the executed leaders. Sinn Fein, too, although it had no sort of connection with the Rising, came in for renewed attention; partly because the militant Volunteers had been nick-named “Sinn Fein Volunteers,” and partly because the dead men had discussed it. Sinn Fein clubs began to be formed and the drastic measures adopted by the British Military Authority to stamp out the secret “pro-German” conspiracy (which they believed to be at the back of the Rising) more than anything else helped to consolidate the rapidly extending Republicanism. From April, 1916, to April, 1918, the military persevered with their policy of repression, a policy the people bore without retaliation and with truly wonderful patience.

The Parliamentary Nationalist Party made desperate efforts to recapture some of their lost standing by securing an abatement of the rigours of martial law. Their failure was ignominious. In April, 1918 the Government announced its intention to apply the Conscription Act to Ireland; and that at the same time a Bill for Home Rule would be passed.

The following figures (based, says the “Labour International Handbook,” upon the incomplete reports of a censored press) give an imperfect idea of the repression during 1917-18:—

|

|

1917

|

1918

|

|

Armed raids on private houses

|

11

|

260

|

|

Arrests for political offences

|

349

|

1107

|

|

Sentences for political offences

|

269

|

973

|

|

Courts martial of civilians

|

36

|

62

|

|

Deportations without trial or charge

|

24

|

91

|

|

Suppression of newspapers

|

—

|

12

|

|

Proclamations suppressing fairs, markets, and meetings

|

—

|

32

|

|

Armed attacks on gatherings of unarmed people

|

18

|

81

|

|

Deaths from prison treatment

|

5

|

1

|

|

Murders of civilians

|

2

|

5

|

It must be remembered that during all this campaign of violent suppression the people endured passively and patiently. “There were,” say observers of the highest competence, “no attacks upon the constabulary; no physical retaliation of any kind.” The people were concentrating their energy upon building up a political machine through which their demand for independence might find adequate expression.

Their chance came with the General Election of 1918. Despite the military terror, the absence of 31 candidates in gaol, and of many others for whom warrants were out; despite the suppression of their meetings, their literature and their newspapers and the general atmosphere of intimidation, the elections gave 75 out of the 105 seats in Ireland to candidates pledged to the formation of an Irish Parliament.

The triumph was complete and unanswerable.

By all the accepted rules of the Parliamentary game, Ireland had declared its Republican Independence, and such of the 75 as were at liberty, proceeded to assemble (January, 1921) and, constituting themselves a Republican Parliament (“Dail Eireann,”) set up a ministry with Eamon De Valera (the only surviving Commandant of Easter Week) as President.

* * * * *

The elections having provided the authorities with ample evidence of the personality of the leading Republicans, they proceeded to use their unlimited powers of arrest and search, to stamp out the Republican organisation. A galling system of espionage, ramifying into every hamlet and farm, was extended over the country, with the inevitable result that, at last driven to desperation, Irishmen began to meet the insulting terror with violent resistance.

During 1919 the R.I.C. remained, as in normal times, dispersed in small groups over a vast number of village barracks and outlying posts. Their individual members remained busy at their work of espionage. The amount

of justification possessed by the Government’s cry of a “murder gang bent upon the assassination of innocent policemen,” can be estimated from the fact that only 11 out of the 11,000 members of this corps were killed during the year and only two of them can be said to have been (in any fair sense of the term) “murdered.” The rest fell in attacks upon patrols, escorts, and (in one case) a barracks.

The activities of the military can be inferred from the following list of accomplishments for 1919, an imperfect list, based as before, on the incomplete reports of a censored press:—

|

Armed raids on private houses

|

13,782

|

|

Arrests for political offences

|

959

|

|

Courts martial of civilians

|

269

|

|

Deportations without trial

|

20

|

|

Suppressions of newspapers

|

25

|

|

Meetings, fairs, and markets suppressed

|

335

|

|

Armed attacks upon unarmed meetings & individuals

|

476

|

|

Extensive sabotage in towns

|

3

|

|

Civilians killed by Crown forces

|

8

|

A development of the guerilla advance came in the spring of 1920. During the winter previous, in consequence of the attacks upon the outlying police posts and barracks, the constabulary were withdrawn from 600 of the smaller of them. These were, in the spring, burnt by the Republicans to prevent their re-occupation; the greater number being burned (for symbolic reasons) during Easter week.

With the country-side thus cleared of the machinery of British Law and Order, an opportunity was presented for the introduction in its place of the Irish Republican alternative. With astonishing rapidity and efficiency Republican police, criminal, and civil arbitration courts were established. By the end of June, 1920, the Republican courts, systematised in parishes and districts, and all under the central control of a Minister of Justice, were at work nearly everywhere in Ireland outside of Eastern Ulster. Except there and in Dublin, the English Courts, deserted, had ceased to function.

The 1918 Election had manifested the will of the Irish people in a manner that no one could mistake. The establishment of the Republican Authority and the functioning of its machinery demonstrated its ability in a manner little short of marvellous.

The success was all the greater because there was developing in the country districts, and quite apart from the revolutionary struggle, all the materials for an agrarian outburst. The war had stopped emigration; the peace had curtailed the trade in and somewhat reduced the price of Irish agricultural produce. A great tension was growing from the need of land for the increasing population—a need which the delays and complications of the British system would have exasperated without satisfying.

The Republican Arbitration Courts, arranged with a minimum alike of cost and delay, sales of land on equitable terms to co-operative groups of settlers, and, at the same time, dealt effectively and drastically with illegal claims, boundary breaking, and cattle “driving.”

“The Republican Courts (says J. L. Hammond) have carried Ireland through an acute agrarian crisis; they have resettled 80,000 acres, and made and enforced awards which have restored peace in the most disturbed districts. Irish landlords may be seen in the Carlton Club, or the Kildare Street Club who have been glad to sell part of their estates to satisfy the land hunger of their neighbours, knowing that they could get better terms from the Republican Courts than they could get in the present state of the stock market under the Government Acts.”

“The crisis is passed (says Erskine Childers), the first of its kind ever to pass peacefully, because the first ever dealt with by Irishmen appealing to Irishmen, to respect the decisions of an Irish Court.”

And Dublin Castle, as malevolent as impotent, classes together, as alike guilty of “Sinn Fein outrage,” the cattle-driver, the boundary-breaker, the witness who testifies to the offence, and the judge who awards a penalty.

* * * * *

The reply of the British Authorities to all this has been indicated above. But to give in anything like adequate detail an account of the orgy of brutality, bestiality and violence that became the normal conduct of the Crown Forces from this point onwards, is utterly beyond alike our powers of description and the limits of our space. A deliberate endeavour was made by the Dublin Castle Authorities to terrify the Irish into an abandonment of their loyalty to the Republic. To gain this end, means were adopted and measures connived at, unheard of in the Russia of the Tzars, and unprecedented except possibly in the Balkans.

This was facilitated by the wholesale resignations from the R.I.C. The places of those resigned were taken by a “Military Auxiliary” Force composed of ex-officers recruited by advertisement, the ordinary ranks being filled from the less desirable elements of English industrial towns, gathered by even more questionable means.

To raids, arrests, and an occasional sack (which continued on an ever-increasing scale) were added systematic assassinations (beginning with Thomas MacCurtain, Lord Mayor of Cork) of leading Republicans. As the coroner’s juries brought in verdicts of guilty against “unknown members of the Crown Forces,” they were abolished and military inquiries substituted.

The Terror extended to mass sabotage. Tuam was invaded, looted, bombed and wrecked, its Town Hall and principal shops burnt and such of its inhabitants as could be captured, were flogged. The same night broke out, amid similar drunken orgies, pogroms in Belfast and other towns in East Ulster.

“Catholics,” says Erskine Childers, “were driven from shipyards and mills, thrown into docks, hunted like game, their homes and shops burned to ashes, or battered and plundered, their churches and halls wrecked by organised Orange crowds, frenzied with drink and carrying Union Jacks as a hint to the troops not to interfere—a hint observed till the worst was over. The death list was twenty-two, with 188 wounded. This pogrom, another at Lisburn (August 23rd-24th), when forty Catholic houses and shops were burnt down, and another at Belfast (August 28th to September 1st) were the first steps in a long matured scheme for the expulsion of Catholics from the district. Tests, nominally political, actually religious, were imposed on their employment; 9,000 of them have been driven from work leaving 30,000 destitute. Then the British Government played its part by forming an armed ‘Special Constabulary’ from the persons and classes who had taken part in this mediæval persecution, after making a creed of the ‘intolerance of Catholics.’ This corps, too, began to kill, loot, and burn.”

Some idea of the “Black-and-Tan” terror—necessarily a vague and imperfect one—can be gained from the particulars given below. The destruction at Tuam was only the prelude to a campaign which continued for the remainder of the year. The following table will give some idea of the result:—

|

R.I.C. killed individually

|

41

|

|

|

Military killed individually

|

1

|

|

|

Total of Crown forces “murdered”

|

|

42

|

|

Republican Army killed individually

|

101

|

|

|

Unarmed Republican civilians killed individually

|

102

|

|

|

Total Irish “murdered”

|

—

|

203

|

|

Civilians (unarmed) wounded by Crown forces

|

|

589

|

|

Guerilla encounters

|

|

313

|

|

R.I.C. killed in action

|

143

|

|

|

Military killed in action

|

51

|

|

|

Total British loss

|

—

|

194

|

|

I.R.A. killed in action

|

|

70

|

The following table should be compared with those given above for 1917-18 and 1919. It must be noted that they include none of the great destruction in the East Ulster pogroms, and also that they are incomplete even then:—

DESTRUCTION BY THE CROWN FORCES IN 1920

|

|

Wholly Destroyed

|

Partly Destroyed

|

|

Factories and small works

|

11

|

3

|

|

Shops

|

225

|

625

|

|

Farmhouses

|

171

|

—

|

|

Hay and fodder

|

299

|

—

|

|

Printing works

|

9

|

3

|

|

Private houses

|

152

|

296

|

|

Public halls and clubs

|

77

|

29

|

At the end of 1920 the British Government tried its usual policy of division by apparent concession. This was prepared for by the proclamation of martial law over the whole of four southern counties, the burning of Cork by the Crown Forces, and the proclamation of the penalty of death under martial law over all Ireland for, not only persons taking part in insurrection, but any person “harbouring and aiding them.” This was a virtual sentence of death against the whole of the Republican five-sixths of Ireland. It was followed by other proclamations threatening death to the Crown forces for “offences against persons or property.” Then followed the master stroke, the Royal Assent to the Act portioning Ireland between two Parliaments (Northern and Southern), with a co-ordinating senate, in which the Northern Parliament had an assured predominance.

Republican Ireland and the Black and Tans alike ignored the Act until the time for the election drew near. The earlier months of 1921 saw a gradual slackening off in the more frantic manifestations of the Terror, although hanging, flogging, and torture to extort confession were added to the methods of British rule. The elections duly arrived (May, 1921). The unconquerable Republicans rose to the occasion and the Southern Parliament was chosen without a ballot. It was composed of four Unionist members for Dublin University and 130 Irish Republicans, who give allegiance to Dail Eireann. In Ulster all the forces of Orangeism were parade. Riots, smashing of motor-vehicles, assaults upon voters and elections agents, seizure of polling booths—all means were employed to make safe an Orange victory, which could hardly be in doubt. Even so, Republican candidates were elected in several cases.

* * * * *

Ireland stands to-day where it was bound to stand under the circumstances. The Irish, by every moral test, have won the independence to which they aspire.

For the time being the situation has been modified by the conclusion (since the foregoing first appeared in print) of a “Treaty” between the British Government and the representatives of Dail Eireann. By virtue of this Treaty an “Irish Free State” has been created, taking rank as a “Dominion” of the British Empire. This, however, is by no means a settlement of the difficulty. The historic struggle for Irish Independence will take new and dramatic forms before the end is reached.

IV.

The Empire and the Worker

IT has been demonstrated by our examination of the cases of India, Egypt and Ireland, that the normal progress of the Imperial system, instead of begetting the unity and solidarity which is imperative if it is to hold together against external attack, does just the opposite. It produces an ever intensifying solidarity of opposition to itself in each of those racial groups which it seeks to bring beneath its sway and which are sufficiently developed historically to put up a national struggle.

More than anything else this is rendered unavoidable by the essential economic foundation of Bourgeois Imperialism—the need to accumulate in the hands of its dominant class an ever expanding bulk of revenue-producing capital which, in its process of expansion, undermines the security of larger and larger areas of the producing mass. This insecurity finds its expression in antagonism first between the producer and the State, whose burdens seem intolerable, then between the exploiting upper and exploited lower strata of the possessors of the means of production, and finally in the struggle of the propertyless wage-worker against at first the effects and finally the essentials of the system of Bourgeois exploitation.

Even if the Imperialist Bourgeoisie in the Home State were willing to come to terms with their counter-parts in the subject nationalities—and they could only do so by sacrificing tempting opportunities for exploitation and thereby creating rival bidders for the available stocks of raw material and dangerous competitors in the diminished world market—this would not solve the problem of class antagonisms, which lie even deeper than those of nationality.

The present situation of the proletarian class-struggle in Britain itself should be sufficiently familiar to readers of The Communist to need no recital here.

What does need emphasis is the relation between the resources of the Empire (alike in potential wealth and labour-power), and the battle of the British worker, in the face of stagnant trade, immobilised credit, rising-unemployment, employing-class solidarity, and the E.P.A., to maintain his hardly-won standard of living. This struggle, too, has its counter-part in the similar and simultaneous struggle of the White section of the workers in the Dominions against a similar (or the same?) attack, attack.

White Workers and Niggers