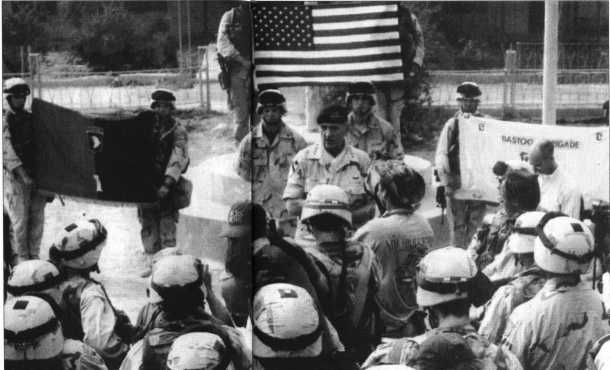

General Tommy Franks and the 101st division prepare to assault Baghdad

From Socialist Review, No.274, May 2003.

Copyright © Socialist Review.

Copied with thanks from the Socialist Review Website.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

The US military may have succeeded in Iraq but now the problems are beginning to mount up

|

|

General Tommy Franks and the 101st division prepare to assault Baghdad |

Defeating Saddam Hussein’s armed forces was the easy bit for US imperialism, even if victory was not quite as quick as the White House had hoped. Its real difficulties start now.

Already there are signs of massive resistance to the continuing US occupation of Iraq on the one side, and of splits over what to do next within the US administration on the other. To understand why, it is necessary to be clear what the war was about.

The anti-war movement quite rightly said it was about oil and US power. But why did the US administration feel the need to assert its power in this way? The answer lies in the long term trajectory of US capitalism over more than half a century.

At the end of the Second World War the US was easily the mightiest economic power, with close to half of world economic output. By the 1990s this was no longer true. US capitalism had grown in the interim, but its European and Japanese rivals had grown even more. And China, with a growth rate three times that of the advanced countries, was beginning to catch up. People like Paul Kennedy began to talk of the long term decline of US power. Henry Kissinger, war criminal and adviser to successive Republican governments, did not go so far, but insisted,

‘The end of the Cold War has created what some observers have called a “unipolar” or “one superpower” world. But the US is actually in no better position to dictate the global agenda unilaterally than it was at the beginning of the Cold War ... The United States will face economic competition of a kind it never experienced during the Cold War.’

Pressure began to emerge within the US political establishment for it to use to effect the one great advantage it had over the other major powers – its military superiority. The Clinton administration began to move in this direction with its expansion of Nato to eastern Europe, its setting up of an inquiry into the Missile Defence System (directed principally against China), its military intervention in Bosnia and its war against Serbia.

This was not enough for the Project for the New American Century of Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, Cheney, and their mentors Richard Perle and William Kristol. It argued in its founding statement:

‘American foreign and defence policy is adrift. As the 20th century draws to a close, the United States stands as the world’s pre-eminent power ... We are in danger of squandering the opportunity and failing the challenge.’

The US should increase its arms expenditure, they argued, and plough the money into the most technologically advanced weapons systems, so as to be able to easily intervene anywhere and everywhere it wanted quickly and with few casualties. Top of the list of interventions should be Iraq. They were able to begin implementing this agenda, ensconced in the White House, as panic swept the US in the aftermath of 11 September 2001.

By this time the economic problems of US capitalism were much clearer than they had been in the mid-1990s. The collapse of the new technology boom revealed that US companies had been claiming profits about 50 percent higher than they really were. And US capitalism had become dependent for its normal functioning on lending from the rest of the world (mainly from east Asia) of around $400 billion a year.

The Bush gang’s answer was to use its military policy to deal with the economic weaknesses. At home, there was to be a return to the Reaganomics of the 1980s, a massive increase in arms spending and enormous tax cuts for the rich, as a way of escaping from recession. Abroad, successive military interventions were to reassert US global power, give it leverage over the oil supplies all the advanced capitalist states depend on, and emphasise that the US was the safest haven for foreigners to put their money in. Such is the Bush administration’s rationale for its war. It is a rationale which is full of holes.

The first hole concerns Iraq itself. The Rumsfeld military doctrine relies on high tech weaponry allowing relatively small numbers of land troops (around 200,000 in this war, as opposed to about three times the number in the 1991 Gulf War) to smash their way into capital cities and that drive out enemy governments. If bigger numbers of troops had to be used, it would be more difficult to threaten repeat wars against other recalcitrant states.

But success on the battlefield does not automatically translate into the wider goal of exercising leverage, through control of oil, over the rest of the capitalist world. It is difficult to see how anything less than a full blooded, long term occupation of Iraq can do that. For any Iraqi government with some local base of support of its own would be tempted to manipulate the price of oil to suit its interests rather than those of US capitalism.

But full blooded occupations need many more troops and are much more expensive than lightning raids. Russia, for instance, used twice as many troops as the US has in Iraq to subdue Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968 – even though Iraq’s population is twice each of those two countries.

It is worth remembering why the European powers retreated from their colonies in the 1950s and 1960s after a century and more of carving up the rest of the world between them. They found it increasingly difficult and costly to hold on to them once modern national liberation movements came into existence and every grievance of any class translated itself into hatred of foreign occupation.

At the same time, the economics of capitalism began shifting against the direct holding of colonies. The most important growth areas for markets and profitable investment were increasingly within the advanced countries themselves. Africa, the centre of inter-imperialist conflicts over the division of territory a century ago, today only accounts for around 0.6 percent of total direct foreign investment, and Latin America only around 6 percent. European colonialism was no longer a paying business once it encountered even minimal resistance.

This points to the second hole in the Bush gang’s strategy. The Middle East is more important for world capitalism than most of Africa and Latin America. Even so, it is by no means certain that US capitalism will gain more than it loses if it goes along the path of full blooded occupation. Control of the oil may not automatically pay for the costs of occupation. Experts estimate that it could take up to five years for Iraqi oil production to reach its optimal level, and even then the low oil prices wanted by US domestic interests to keep them happy would imply limited oil revenues for the occupation forces.

The US troops were facing new resistance from Shias and Sunnis alike within 24 hours of the collapse of the Saddam regime. If the troops are still there in large numbers in five years time, when the oil flows fully, it is difficult to see how they will avoid resistance many times greater. Indeed, even small numbers of troops can provoke immense resentment, not just in Iraq but right across the region. After all, there are only 5,000 US troops permanently based in Saudi Arabia, and that was enough to give rise to Al Qaida.

These factors explain why the US administration, having taken Baghdad, is split down the middle over what to do next. One section believes it is the US’s mission to reshape the whole region in its own interests, however long it takes. It imagines it can set up stable pro-US regimes, run by privileged elites capable of gaining some sort of legitimacy through elections, as happened in Central America at the end of the civil wars and US interventions of the 1980s. Another section insists such ‘nation building’ is too expensive and the US has to get out as quickly as possible, leaving behind a pliant government, however arbitrarily chosen. Any other course, its says, puts it at risk of getting bogged down Vietnam style, and having to throw in ever more troops just to hold on to what it already has.

In all probability it will end up getting the worst of both worlds, occupying the country with too few troops to do so effectively, its soldiers hitting out wildly in an attempt to keep control of an increasingly hostile population, and further increasing their hostility. In its attempts to establish pliant governments, its easiest route would be to rely on the same middle and upper class Sunnis that Saddam did – and probably on much of the Baathist apparatus acting under a new name. This would, of course, alienate the Shia religious leaders and lower classes, turning them further against the US presence, making US withdrawal difficult but continued US occupation politically and economically ever more costly.

The third hole in the US’s strategy lies in its inability to do more than scratch at the surface of the wider problem facing US capitalism. It is going to find it very difficult to translate its enhanced military power into more favourable figures in the accounts of US corporations. No doubt the US government will find it a little easier to frighten more Third World governments into opening their economies up to US firms, to keep paying their debts and to do what the IMF tells them. No doubt there will be some improvement in the profits of the oil, arms and contracting companies which have gained directly from the war. But that will not be enough to squeeze out of the rest of the world the huge sums of extra surplus value needed to raise US profit rates to the level they supposedly were at five years ago. And, without an increase in profitability, the arms spending and tax cuts will make the problems of the US economy worse, not better. There will be increased dependency on the inflow of lending from the rest of the world – an inflow it is easy to envisage being interrupted with catastrophic results by crisis at home or abroad. This prospect will increase the infighting within the US ruling class as to what to do next, with the Project gang tempted by further displays of military might and deeper unease among other sections as to where this is leading them.

The Bush gang and their generals need to get their victory celebrations over quickly. There is unlikely to be much for them to celebrate in a year or two.

Last updated on 27 December 2009