From Socialist Review, No.236, December 1999.

Copyright © Socialist Review.

Copied with thanks from the Socialist Review Archive at http://www.lpi.org.uk.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

|

The approach of a new millennium is hailed as time to celebrate the success of western civilisation and the great achievements of capitalism across the globe. But for millions around the world there seems to be little cause for celebration. They bear the brunt of the horrors of the system. Yet there is a history we are proud to celebrate of people fighting back and glimpsing the possibilities of a different kind of society. In a special feature we examine the tremendous changes of the last 1,000 years. We begin with Chris Harman who argues against the idea that the west has been the civilising influence of world history |

|

We have all been brought up on myths about the ‘superiority’ of the west. These assume that there has been a single line of civilisation going back to Greece and Rome, involving over the last 2,000 years a ‘Judaeo-Christian inheritance’ which has been more ‘civilised’, more innovative or more ‘humane’ than that to be found in the rest of the world. The notion of a continuous tradition, supposedly responsible for the rise of industrial capitalism in Europe, is still to be found today, for instance in David Landes’s influential book The Wealth and Poverty of Nations and in Ellen Meiskins Wood’s Peasants, Citizens and Slaves. Even some people who reject any notion of the ‘superiority’ of the west accept the myth of continuity, but in a mirror image way. Edward Said’s Orientalism, for instance, sees a single, iniquitous culture of contempt for the rest of the world as characterising European thought from the time of Aeschylus (5th century BC) through the rise of Christianity and the Crusades up to modern imperialism.

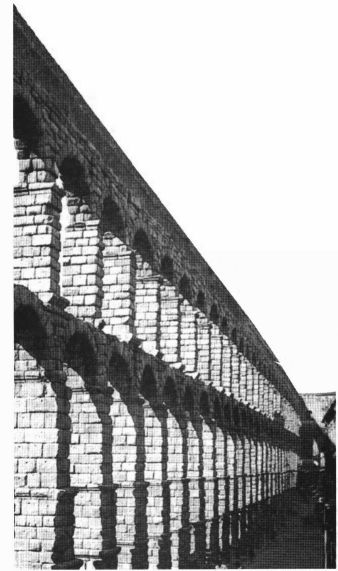

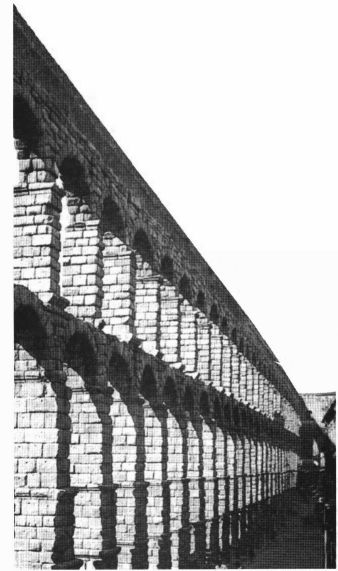

In fact, history has not developed like that at all. A thousand years ago north west Europe was one of the most backward parts of the world. It was made up of Iron Age societies with very few towns and no real cities. Homes and even castles were made of wood coated in mud, clustered together in villages separated by forests, wasteland or marshes. There were no proper roads between them, and any travel over land was along rough tracks, on foot, by mule, or sometimes on horseback. Most lords were as unable to read and write as the vast mass of peasants they exploited. What passed as literature was produced in monasteries, and mainly involved the copying by hand of old religious texts. Insofar as there was a ‘Graeco-Roman inheritance’ in Europe, it amounted to a handful of texts in Latin which might be read, at any point in time, by an even smaller number of monks.

There was a huge contrast with this state of affairs if you looked eastwards to the Arab lands and China, or westwards to Central and South America. The biggest cities in the world were undoubtedly in China, followed by places like Baghdad and Cairo. Even 800 years earlier, when Rome was at its prime, Teotihuacan (outside present day Mexico City) was as big as Rome, while in the 14th century Vijayanagar in southern India was bigger than Paris or London.

Merchant caravans made long overland journeys from northern China through Samarkand and Bukhara to northern India, Tehran, Baghdad and Constantinople. One set of sea routes connected southern China with southern India, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, down the eastern coast of Africa to Zanzibar, and beyond. Another maintained regular contact between Egypt, present day Algeria and Morocco, right up into an Islamic civilisation in Spain that was to last more than 700 years.

The great mass of the population still lived in the often vast areas between the cities, working as peasants scratching the land to provide for a livelihood for themselves and paying rents and taxes to ruling classes. But within the cities there developed a level of literacy, artistic culture, and scientific and technical advance way beyond that even dreamt of in Europe. It was within the Indian and then the Arab civilisations of the first millennium that people pioneered our present numerical system, discovered the use of zero, advanced the calculation of pi, estimated the size of earth (more accurately than Columbus did five centuries later), and continued and enriched the philosophical traditions established in Greece and Greek Alexandria at a time when knowledge of these was minimal in Europe. China in these centuries was already deploying many thousands of water mills and manufacturing cast iron and steel in bulk, and went on to witness the invention of paper, gunpowder, the first clockwork clocks and the mass printing of books five centuries before Europe, as well as the development of shipbuilding and navigating techniques (the compass, for instance) that allowed long distance ocean voyages.

How did such developments occur? And why were parts of Europe in the next millennium able to catch up, overtake and eventually conquer the heartlands of the older civilisations? There are currently fashionable explanations which see things in terms of the different ‘cultural’ features of the different civilisations. This runs through, for instance, David Landes’s account, and has been the rationale for the BBC’s series on the millennium. But this does not explain where the different cultures came from. It does not explain why Hinduism, rather than, say, Buddhism, came to dominate the Indian Middle Ages, why Confucianism defeated rival ideological systems in China, or why medieval Islam differed in important ways from Islam at the time of the 7th century.

The different ‘cultures’ were, in fact, the product of historical development, not its cause. And they were not separated off from each other. We can trace the spread across Eurasia and Africa (and, separately, across the Americas) of the great innovations which increased the ability of human beings to make a livelihood and transformed the societies they lived in. So wheat first domesticated in the Middle East made its way to the Atlantic coast of Europe, north Africa and the Pacific coast of China; rice from southern China reached west India; iron spread out from Asia minor to the whole of Eurasia over a 1,500 year period; steelmaking from west Africa diffused down into the centre and east of the continent over a similar time span; the camel domesticated in Asia about 1000 BC opened the way to commerce through the Sahara and to the transformation of Arabia in Mohammed’s time; horse harnesses from central Asia and gunpowder, compasses and paper from China were essential prerequisites for the development of late medieval Europe.

|

Each culture arose as a transitory facet of a single process of world history (or possibly of two similar processes, one in the ‘old world’ and one in the ‘new world’, until they clashed in the time of Columbus and Cortes). At different times and in different parts of the world the development of human control over nature was accompanied by the concentration of wealth into the hands of ruling classes, and with this the growth of ‘civilisation’ in the full meaning of the term – the growth of towns, the use of writing, the establishment of full time groups of traders and artisans, the rise of organised religion. Humanity’s level of material production was such that without an exploiting minority squeezing wealth out of the toiling majority there could he no concentration of the resources needed for civilisation to take off. This is why the successive civilisations and accompanying cultures to be found in Africa, Asia, Europe and North and South America were all based on such exploitation.

But in every case a ruling class whose initial rise was associated with advances in the creation of wealth later became an impediment to further advance. Typically, civilisation expanded up to a certain point, but then began to go into reverse as the level of exploitation by the ruling class made it difficult for the mass of people to produce the things needed to keep society going. So the first great civilisations of Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, Egypt, Crete and mainland Greece had all experienced ‘Dark Ages’ of greater or lesser severity by 1400 BC. There followed the rise in the first millennium BC of the classical Greek, Roman, Indian and Chinese civilisations. But these in turn ran into great problems by AD 500. Europe fell back into its ‘Dark Age’, with virtually no industry, trade or literacy. In India trade and the towns declined, artisan production deprived of markets retreated into virtually self contained village units, where it became organised by castes, and literacy became a virtual monopoly of Brahmans and entangled with superstition. It was at this point that Hinduism finally ousted Buddhism as the dominant religion and the fully formed caste system took root. China did not experience a relapse on anything like the same scale, but the empire fragmented in the 3rd century AD, and there was a 200 year gap before there was a revival of trade, urban life and learning.

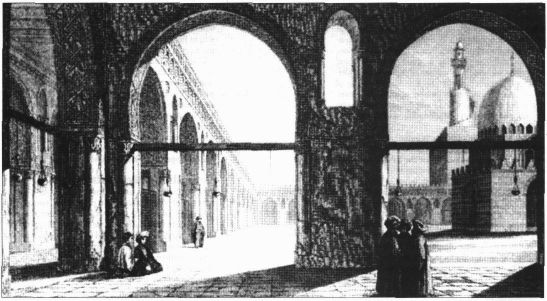

In the Middle East and Mediterranean region the advance of civilisation was associated, for the best part of half a millennium, with the rise of a new religion, Islam. In the towns of the Arabian peninsula a new trading class had emerged, unencumbered by old parasitic classes. The prophet Mohammed had provided it with a worldview which enabled it to defeat the decaying empires around it and establish a new empire which encouraged trade, artisan industries and urban life. Literature, science, art and philosophy flourished here as nowhere else for several centuries, developing traditions established in ancient India, Egypt, Greece and Rome, and passing them on to subsequent civilisations.

By 1000 AD the Islamic Empire was decaying at its heart. Mesopotamia had known the most fruitful agriculture anywhere in the world for some thousands of years, based upon a network of canals linking the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The Islamic rulers had initially cleared and refurbished canals neglected by their predecessors. After three centuries, however, the Islamic ruling classes too had become bloated and parasitic, willing to ravage the countryside in order to provide for their own luxury consumption. The land around the old Islamic capital, Baghdad, became barren and desolate, and the Islamic world was torn apart by revolts and civil wars. Islamic culture, now centred in cities like Cairo, Cordoba in Spain, Bukhara in central Asia and Timbuktu in west Africa, remained in advance of any in Europe for some time, but had lost its old dynamism.

The revived Chinese civilisation was still very dynamic in 1000 AD. Under the Sung Empire, there was a growth of trade and industry such as humanity had never known and was not to know again until after the European Renaissance of the 16th century. Indeed, without the advance of Sung China, the Renaissance – and the rise of capitalism which it heralded – would have been impossible. But by 1200 AD Chinese civilisation too was beginning to be stifled by the sheer opulence of a parasitic ruling class. A Turkic people established a rival empire, the Chin, over northern China, leaving the Sung dynasty with the south alone until, in the 13th century, both were conquered by a former herding people, the Mongols.

The same centuries saw the Mongols tear into the vestiges of the Islamic Empire in Iran and Mesopotamia and ravage northern India and eastern Europe. The name of their leader, Genghis Khan, has become a byword for wanton savagery. Yet they too were the product of circumstances, not a cause. Living and herding on the edges of great civilisations, they could learn from them, especially when it came to military weaponry, and then use their learning to great effect against the bloated ruling classes of neighbouring states. Nor was the effect of the Mongol rampage from one end of Eurasia to the other wholly negative. It helped transmit knowledge of techniques developed in the civilisations of the east to the lands of the west.

The Mongols were not the only people whose past ‘backwardness’ left them unencumbered by the parasitic baggage. A new chain of civilisations flourished in this period in Africa, stretching below the Sahara from the Nile westwards across the continent and putting the past advances of the Islamic civilisations to new uses. And in western Europe advances in agriculture learned from the east combined with a new way of organising exploitation, serfdom, to produce a couple of centuries of rapidly growing food output. This soon produced, in turn, traders, towns and urban classes capable of taking up the industrial as well as the agricultural practices of the older civilisations. By the 13th century cathedrals were being built where there had not even been stone houses 380 years before, and pioneering intellectuals were making the long trek to Toledo in Spain to get access to the writings of Islamic philosophers and mathematicians, along with Arabic translations of Greek and Latin classics.

Even then, however, Europe was still far short of leading the rest of the world. In the 16th century its technology was only at about the same level as that of the Mogul Indian Empire, of the Ottoman Empire that had arisen in Asia minor to conquer the Middle East and most of eastern Europe, of the Islamic states along the Niger in Africa, and of the Min Empire that ruled China. If it eventually overtook these to carve out world empires it was because its past backwardness made it easier for its merchant and artisan classes to transform the whole of society in their own image. They had the advantage over their Chinese, Arab and Indian equivalents of arriving late in the game of world history. Even so, it took more than 300 years of political, ideological and economic struggle before they could enjoy full success.

Chris Harman’s new book, A People’s History of the World, is published by Bookmarks Publications £15.99.

Last updated on 22 December 2009