Published: Charles H Kerr Co-operative, 1911;

Transcribed: Sally Ryan for marxists.org, 2000.

If you are a working man or woman, no matter what you do in the shop or factory, or mine, you know that there are two kinds of power used in the plant–human, or labor power, and steam, or water (or perhaps–gas explosion) power.

The owner of a new barrel mill in Indiana decided it would be cheaper to have some company furnish power to run his mill than to install a power plant himself, so he sent for the three representatives of the three power plants in that city.

The first man came from the company that offered to run the machines in the mill by steam power; the second came from a firm which wanted to sell him a gasoline engine to furnish the power by the explosions of gas, while the third came from a great water-power company. This man offered to supply power to run the mill machinery at a lower price than the others asked. Of course, he secured the contract.

By this time the mill owner was almost ready to have his plant opened. He had logs (or raw material) ready to start on; he had machinery and power to run that machinery. Only one thing more was needed to start the plant running and to produce staves and hoops for barrels. This was the commodity which you workers supply. It is human power, human labor-power.

One hundred years ago almost everything was produced by human labor-power, but gradually improved machinery has been invented that lessens the human toil needed to make things. Big machines, run by steam, or water-power, now do most of the heavy and difficult work. But the owner of the mine or factory or mill needs one other commodity to guide the machines, to tend the machines and feed them. He needs your labor-power.

The barrel manufacturer in Indiana said he needed "hands." He meant hands to do things. He meant labor-power. So he put an advertisement in the paper reading "Men Wanted," Of course he did not want to buy men outright, as folks used to buy chattel slaves. He hired some of you to work for him. He bought your human power (to work)–your labor power.

And you sold him your labor-power, just as a stockman sells horses or a baker sells bread. You went to the boss with something to sell. He was in the market to buy human labor-power, and if your price was low you probably got a job.

Some of us work many years before we realize that even we wage-workers have one commodity to sell. As long as we are able to work we try to find a buyer of our labor-power. We hunt for a job and the boss that goes with a job.

Men and women who have no other means of support have to sell their labor-power for wages in order to live.

A commodity is something that satisfies some human want; something produced by labor-power for sale or exchange. A dress made by a woman for herself is not a commodity. A dress made to be sold to somebody else is a commodity. It is not made for use, but for sale.

Sheep are commodities, as are shoes, houses, gloves, bread, steam-power and water-power, when sold by one man to another. And your strength to make things, your human laboring-power (or, as Marx says, your labor-power) is also a commodity when sold to an employer for wages.

Now you know that any man who is selling a commodity asks as high a price for it as he can. The little grocer who runs the small store near your home charges just as much as possible in selling butter to you. The coal dealers raise their prices whenever they can. And when you strike the boss for a job, you ask him as high a price for your labor-power as you think you can get.

High prices for labor-power is what wage-workers want. Low prices for labor-power is what your employer wants.

Are your interests identical?

What happens when there are ten men competing to sell their labor-power? Who gets the job?

What happens when there are several jobs and only one worker? Will he receive higher or lower wages? Will he get a good price for his labor-power?

When workingmen are scarce and manufacturers are forced to pay a high price for labor-power (high wages) in a certain locality, does the scarcity of workers last long? If not, why not?

When men are hunting jobs toward which cities do they go? Why?

Does supply and demand have anything to do with the price at which you are able to sell your labor-power?

Why is the steel trust putting up a fifty million dollar plant in China? Will they be able to make more profits manufacturing steel there than in America? Why? Why do Chinese workmen come to America to sell their labor-power?

Karl Marx talks much of commodities–their value and their price, and in order to understand his teachings, we must know first of all that we are sellers of a commodity called labor-power.

In the next lesson we shall take up the question of what determines the value of your labor-power and the value of all other commodities.

We suggest that students buy and study Capital, by Marx; 3 vols; cloth, $2.00 each.

Value, Price and Profit, by Marx, 10 cents.

These lessons are only an attempt to say, in the language of working men and women, the things Marx says in his own books.

In the preceding chapter, we learned that the wageworker's relation to the boss is that of a seller of a commodity. Whether you work in a mine, a mill or a factory, whenever you get a job you are selling your strength to work–or your labor-power–to the boss.

We know that labor-power is a commodity like shoes or hats or stoves.

Now all commodities are the product of labor, that is, there was never a commodity that was not the result of the strength and brains of working men or women. Workers make shoes; bakers of bread are working men or women; houses, street cars, trains, palaces, bridges, stoves–all are the product of the laboring man. All commodities are the product of labor.

There is one common thing which all commodities contain. This is labor. A commodity only has value (exchange value) because it contains human labor.

Horses are commodities, cows are commodities, gold: is a commodity. Human labor has been spent in producing all these. Labor-power is also a commodity, the result of human labor in the past.

Working men and women spent labor producing you and me. Somebody made bread, sewed shoes, built houses and made clothes for us. All the things we ate and drank and wore and used were made by the labor of working men and women. Their labor was necessary labor. Without it we should never have grown old enough or strong enough to have labor-power to sell. Labor-power was spent in raising as to the point where we would be able to work.

The value of a commodity is determined by the social labor-time necessary to produce it. On page 61 of the Kerr edition of Value, Price and Profit, Marx says:

"It might seem that if the value of a commodity is determined by the quantity of labor bestowed upon its production, the lazier a man, or clumsier a man, the more valuable his commodity, because the greater the time of labor required for finishing the commodity. This, however, would be a sad mistake. You will recollect that I used the word social labor, and many points are involved in this qualification.

"In saying that the value of a commodity is determined by the quantity of labor worked up or crystalized in it, we mean the quantity of labor necessary for its production in a given state of society, under certain social average conditions of production, with a given social average intensity, and average skill of labor employed."

If you spend three months cutting up a log with a pen-knife into a kitchen chair, it will be no more valuable in the end than the kitchen chair made in the big factories where many men working at large machines produce hundreds of chairs in a single day.

Of course we know that every new improvement in machinery lessens the labor-time needed in making certain commodities. Oil is less valuable than it was ten years ago because it takes less labor- power to produce it. Steel has fallen in value, because owing to the new and improved machinery used in making steel it requires less human labor-power for its production.

Suppose every shoe factory in the country were working full time in order to supply the demand for shoes. The factories using the very old fashioned machinery would require more labor to the shoe than the factories using newer machines, while the great, up-to-date factories using the most modern machines would need comparatively little human labor-power in producing shoes.

The value of shoes would be determined by the average (or social) labor-time necessary to make them, or the socially necessary labor contained in all the shoes.

The value of gold or silver is determined in the same way. The necessary social labor needed to produce gold gives it its value. The value of gold rises or falls just as the value of other commodities rise or fall. Today gold is much lower in value than it was twenty years ago, because new methods of production have reduced the social labor needed in gold mining about one-half. If you have twenty dollars in gold it is only of half the value of twenty dollars twenty years ago. It contains only half the labor.

In the same may we may determine the value of laboring-power "Like every other commodity its value is determined by the quantity (or time) of labor necessary to produce it.

"The laboring-power of a man exists only in his living individuality. A certain mass of necessaries must be consumed by a man to grow up and maintain his life. But the man, like the machine, will wear out, and must be replaced by another man. Besides the mass of necessaries required for his own maintenance, he wants another amount of necessaries to bring up a certain quota of children that are to replace him on the labor market and to perpetuate the race of laborers....It will be seen that the value of laboring-power is determined by the value of the necessaries required to produce, develop, maintain and perpetuate the laboring-power." (Value, Price and Profit, pp. 75-76.)

The value of a man's labor-power is determined by the social labor necessary to produce it, Marx says. This means food, clothing, shelter (the necessities of life) and it means something additional to rear a boy or girl to take your place in the shop or factory when you grow too old to keep up the fierce pace set by the boss.

Enough to live on and to raise workers to take our places–this is the value of our labor-power, if we are wage-workers.

What is a commodity? What does the wage-worker sell to his employer?

What determines the value of a commodity?

What do you mean by SOCIAL labor-power?

Are matches less valuable now than they were ten years ago?

Why?

Have commodities in general decreased in value in the last tell years of improved machine production? Why?

Name commodities that have decreased in value. Has rubber increased in value? Why?

Does it take less labor power to weave cloth, to make cement, to slaughter hogs than it did twenty years ago? Why?

Remember that SCARCITY may cause a commodity to exchange (sell) above or below its value, but it does not make value. Marx says that Value is human labor (in the abstract).

Every class should, have at least one set of Marx's Capital for reference in connection with these lessons. The Table of Contents in these three volumes is a splendid guide to students. Price, $2.00 a volume. For $6.00 sent us for six NEW REVIEW subscriptions,

we will send the three volumes as premiums, prepaid expressage.

The value of a commodity is determined by the necessary social labor contained in it. If some one told me that an overcoat was equal in value to the value of (or contained in) a suit of clothes, I would know that the overcoat and suit of clothes were equal in value because they contained equal quantities of the same common thing–labor.

Generally speaking the value of four pairs of trousers is about equal to the value of one coat. Why is the coat more valuable than the trousers? And what determines the measure of value when we come to exchange commodities?

You exchange your labor-power–to the boss–for perhaps $2 in gold a day, and in turn the gold is exchanged for the necessities of life–food, clothing and shelter. Why do these commodities exchange for each other?

As we, learned before, labor is the measure of value. The coat, mentioned above, exchanges for four pairs of trousers because the coat contains four times the quantity of social-labor that one pair of the trousers contains.

The necessary social labor contained in a commodity (shoes, coats, gold, bread, your labor power or whatever it may be) determines what it will exchange for. The natural tendency is for commodities of equal value to exchange for each other, or for other commodities of equal value.

For example: the amount of wheat produced by ten hours of necessary social labor time will exchange for the amount of cloth, shoes, chairs, gold or some other commodity that will be produced by ten hours of necessary social labor.

The value or values for which commodities will exchange change constantly as the social labor necessary to their production changes. Last month we read of a new molding machine that enables one boy to produce as many castings in one day as four men had been accustomed to produce. These castings have now greatly decreased in value (in the individual plant where the new process is used) but the total value of castings in general has been only slightly reduced. The average labor necessary to produce castings is only a little less than formerly. When the new process becomes general and the average necessary labor greatly reduced; castings will greatly decrease in value.

"If we consider commodities as values, we consider them exclusively under the single aspect of realized, fixed, or, if you like, crystalized human labor. In this respect they can differ only by representing greater or smaller quantities of labor, as for example, a greater amount of labor may be worked up in a silken handkerchief than in a brick.

"A commodity has value, because it is a crystalization of social labor.....The relative values of commodities are, therefore, determined by the respective quantities or amounts of labor worked up (or contained) in them." (Pages 56 and 57, Value, Price and Profit).

"In calculating the exchangeable value of a commodity we must add to the quantity of labor last employed, the quantity of labor previously worked up in the raw material of a commodity, and the labor bestowed in the implements, tools, machinery, and buildings, with which labor is assisted." (Value, Price and Profit, page 60).

The value of barrels, for example, is determined by the social (factory) labor spent in producing staves and hoops and the labor time used in producing the portion of machinery worn out in making them, as well as the necessary social labor spent in cutting and hauling (producing) raw logs for use in the mill.

Every time more social labor is needed in making commodities–shoes, hats, gloves, stoves or cigars–whatever these commodities may be–their value is increased. Every time the quantity of socially necessary labor is lessened in the production of commodities, their value is decreased.

Nearly all kinds of furniture have greatly decreased in value the past few years owing to the improved machines used in their production and the relatively small quantity of labor contained in furniture.

Gold has steadily been decreasing in value in the past ten years owing to the improved methods of producing gold and the decreasing quantity of labor contained in it.

Rubber is steadily growing more valuable because the available world supply has been nearly exhausted and it requires more time hunting or planting, and caring for rubber trees–more labor is contained in a pound of rubber than a few years ago.

Gradually we see huge machines replacing the smaller ones in all the great producing industries and, with the constant introduction of more improved machinery, the quantity of human labor contained in commodities produced by modern methods–grows less and less. Such commodities decrease in value with every decrease in the labor embodied in them.

Price is the money name for which commodities exchange. We are accustomed to figure in gold prices. All our bank-notes read "payable in–so much–gold." But gold is a commodity just like bread, or overcoats, or dresses or automobiles. And commodities tend to exchange for the sum of gold containing a quantity of labor equal to the quantity of labor contained in them.

That is, if ten dollars in gold contains forty hours of necessary labor, that gold will exchange for (or will buy) as many pairs of shoes as forty hours of social labor will produce.

Generally speaking, a commodity containing ten hours of necessary labor will tend to exchange for gold, or any other commodity containing ten hours of necessary labor.

This is true whom price and value are equal. But supply and demand cause commodities to exchange (or sell) above or below their value, temporarily.

A temporary shortage in coal–when the supply does not equal the demand–may enable the dealers to exchange coal above its value for a short time. An over supply of automobiles may cause the manufacturers to offer to sell (or exchange) autos below their value, for a time.

Prices are often a little above or below the value of commodities, but they are always inclining toward the value of commodities.

(Please remember that we are not here speaking of monopoly prices. We shall consider them in a later lesson.)

"If supply and demand equilibrate each other, the market prices of commodities will correspond with their natural prices, that is to say with their values, as determined by the respective quantities of labor required for their production...If, instead of considering only the daily fluctuations, you analyze the movement of market prices for longer periods...you will find that the fluctuations of market prices, their deviations from values, their ups and downs, paralyze and compensate each other; to that, apart from the effect of monopolies and some other modifications I must now pass by, all descriptions of commodities are, on the average, sold at their respective values or natural prices.

"If, speaking broadly, and embracing somewhat longer periods, all descriptions of commodities sell at their respective values, it is nonsense to suppose that profit, not in individual cases, but the constant and usual profits of different trades, spring from the prices of commodities, or selling them at a price over and above their value...

"To explain the general nature of profits, you must start from the theorem that, on an average, commodities are sold at their real values, and that profits are derived from selling them at their values that is, in proportion to the quantity of labor realized (or contained) in them.

"If you cannot explain profit upon this supposition, you cannot explain it at all." (From value, Price and Profit, pages 68, 69 and 70.)

Why does skilled labor-power sell (or exchange) at a higher price (for more gold) than unskilled labor? Does the fact that it requires more LABOR to produce a skilled laborer, that it takes more years of feeding, clothing and shelter to PREPARE a skilled workman, have anything to do with the VALUE of their labor-power?

Mining experts tell us that it takes much less labor-power to produce the commodity–gold, than it did a few years ago. Have you noticed that your gold (or money) exchanges for fewer commodities nowadays than it did ten years ago?

Wheat is produced for a world market. Do you think wheat has decreased much in value in the past ten years as compared to the decrease in value (or social labor necessary) of steel?

We believe it takes very nearly as much labor-power to produce a bushel of wheat (on the AVERAGE) as it did in 1900; hence its value must have remained nearly the same.

Why then will a hundred bushels of wheat today exchange for MORE gold dollars than it did in 1900?

If the VALUE of both commodities had remained the same and no monopolist controlled the world's wheat or gold supply, they would exchange upon the same basis as formerly. That is, the same amount of gold would exchange for (or buy) the same amount of wheat.

Does the decreased value of GOLD result in the farmer getting a higher price (or more gold) in exchange for his wheat crop?

(Do not forget that, as Marx says, if we cannot explain profits upon the basis that all commodities exchange at their values, we cannot explain them at all.)

Our next lesson will take up Surplus Value, which explains how capitalists make profits even though all commodities exchange at their values.

Remember that we do not sell our labor. We sell our strength to work or our laboring power, our labor power. Labor is the expenditure of labor-power. See Value, Price and Profit, pages 71, 72 and 73. When we apply for a job, we do not offer to sell our WORK, but our strength to WORK. The commodities we make are crystallizations of our work or of our LABOR, but it is our strength to labor, or laboring power–our labor power which we sell to the boss.

Many of us have been accustomed to think that profits are made from graft, from special privileges or from monopoly. We have talked so much of the thieving among capitalists that we have altogether overlooked the great, main method of profit taking.

As Marx says, if you cannot explain profits on the supposition that commodities exchange at their values, you cannot explain them at all.

And so we shall assume (as in truth they generally do) that commodities on the average, exchange at their value.

Suppose that it takes two hours of necessary labor to produce the necessaries of life for a workingman–or, in other words, two hours of labor a day to produce laboring-power.

Suppose too (as is very likely the case), that $2.00 in gold represents two hours of labor.

Now the value of labor-power (which the workingman sells) is determined (as the value of all commodities are determined), by the social labor contained in it. It is represented by the necessities of life, produced by two hours of necessary labor a day.

If the workman sells his labor-power at its value, he will receive in return a commodity containing two hours of necessary social labor. In the case we mention above, he would receive $2.00 a day.

In other words, a day's labor-power represents two hours of labor, embodied in the food, clothing and shelter that produce it, just as the two dollars in gold (or an equivalent) represent two hours of necessary labor. The labor-power is equal in value to the value of the $2.00 in gold. The workman has sold his labor-power at its value.

The workman receives enough ($2.00) in wages to eat, drink, to rest and clothe himself–enough to produce more labor-power. He receives the value of his labor-power.

But wage laborers sell their laboring-power to the bosses by the day or by the week, at so many hours a day. The capitalist buys the commodity (labor-power), paying for it at its value. If the wage worker is a miner, in two hours he will dig coal equal in value to his wage of $2.00 a day. The coal he digs will contain two hours of labor just as the two dollars in gold contain two hours of labor and as the necessaries for which he exchanges his two dollars, contain two hours of labor.

In other words, in two hours (of necessary labor) the miner would have produced value in coal equal to the value of his wages (or his laboring-power). But he sells his labor-power by the day or week and the boss prolongs the hours of work as far as possible.

In two hours, however, the miner has produced enough value to pay his own wages, but the boss, having bought the laboring-power by the day, may be able to make the wage-worker work ten hours daily. The miner needs only to work two hours to produce a value of $2.00 to reproduce his labor-power. As Marx would say:

He must daily reproduce a value of $2.00 (which he will do in two hours), to daily reproduce his labor-power.

But when he sells his laboring-power to the boss the boss acquires the right to use his labor-power the entire day–as many hours as the worker's physical endurance will permit.

If he forces the miner to work ten hours daily, the workingman will be laboring eight hours beyond the time necessary to pay his own wages (or value of his labor-power). These eight hours of surplus labor are embodied in a surplus value or a surplus product.

In two hours the miner produces in coal value sufficient to pay for his labor-power, but in the eight succeeding hours of labor, he will produce coal valuing $8.00, all of which the capitalist retains for himself.

Since the miner sold his laboring-power to the capitalist, the coal, or value the miner produces, belongs to the capitalist.

Thus the capitalist spends $2.00 a day in wages (or two hours of labor) and acquires coal, or other commodities, equal to $10.00 (err ten hours of labor). Thus come profits.

Year after year the capitalists buy labor-power, paying for it at its value (in the case of the miner at $2.00 a day). The capitalists own the products of the workers–equalling ten hours of labor. They exchange a commodity (gold, or money), containing two hours of labor for labor-power (containing two hours of necessary labor-represented by the necessities of life). But when the miner goes home at night the capitalists find themselves owners of the coal he has dug, which contains ten hours of labor.

Coal (representing ten hours of labor) will exchange for gold (or money) containing ten hours of labor; in this case for $10.00. The miner has produced $10.00 worth of coal. He received $2.00.

The eight hours of value, or $8.00 worth of coal, which the capitalists appropriate, is surplus value, for which they give no equivalent.

"It is this sort of exchange between capital and labor upon which capitalistic production, or the wages system, is founded, and which must constantly result in reproducing the workingman as workingman and the capitalist as a capitalist.

"The rate of surplus value, all other circumstances remaining the same, will depend on the proportion between that part of the working day necessary to reproduce the value of the laboring-power and the surplus time or surplus labor performed for the capitalist. It will, therefore, depend on the ratio in which the working day is prolonged over and above that extent, by working which the working man would only reproduce the value of his laboring-power or replace his wages." (Page 81, Value, Price and Profit, by Karl Marx.)

The capitalist owns the product of his wage-worker. When he sells this product he disposes of commodities a part of which have cost him absolutely nothing, although they have cost his workman labor.

It is easy to see how the miner received the value of his laboring-power; $2.00 gold contain two hours of labor, $2.00 exchange for–or will buy–the necessaries of life (produced by two hours of labor) which will enable the miner to produce more labor-power for the next day's work.

In this case the miner's product, the coal he digs in one day, contains five times the quantity of labor needed to produce the necessaries of life, which produce, in him, more strength or more labor-power.

For the things he gets for his labor-power contain only two hours of labor, while the things he produces, and which are claimed by the capitalist, contain ten hours of labor.

The miner sells his labor-power and, naturally, the capitalist desires to use it as profitably (for himself) as possible. If the wage-worker demanded commodities in exchange for his products, containing an equal quantity of labor, he would no longer be a wage-worker, for capitalists mould no longer employ him. There would be nothing–no surplus value–left for the capitalists.

But men and women who have nothing to sell but their labor-power have no choice in the matter. They are compelled to sell their strength or labor-power in order to get wages to live. Capitalists, on the other hand, employ them for the sole purpose of taking profits. Capitalists are forced to give the working class enough to live and work on, but they try by every means at their command to prolong the working day into ten, or even twelve hours, in order that more surplus products, or surplus value, may remain for themselves.

But intelligent workmen and women are not content with selling their laboring-power at its value. They are coming more and more to demand the value of their products. We are growing weary of being mere commodities, compelled to sell ourselves, for wages at the regular "market price." We are weary of receiving a product of two hours of labor for products containing ten hours of our labor. We are tired of living on meagre wages while we pile up millions for the capitalist class.

This is the chief demand of socialism; that workingmen and women cease selling themselves, or their strength, as commodities. We propose to own the commodities we produce ourselves and to exchange commodities containing a certain quantity of necessary social labor, for other commodities representing an equal quantity of necessary social labor.

You and I work for the boss because he owns the factory or mine or railroad or the mill. Ownership of the means of production and distribution (the factories, land, mines, mills–the machinery that produces things) makes masters of capitalists and wage-workers of you and me.

Socialists propose the ownership, in common, of the mines, mills, factories and land, of all the productive industries, by the workers of the world.

When you and I and our comrades own the factory in which we work, we will no longer need to turn over to anybody the commodities we have produced. We shall be joint owners of the things we have made socially. We shall demand labor for labor in the exchange of commodities. This is the kernel of socialism. It proposes to make men and women of us instead of commodities to be bought and sold upon the cheapest market as men buy shoes or cows.

In the illustrations given above, can the mine owner pay the mineworkers the value of their labor-power and still make a profit? Can the mine owners sell coal at its value and pay the mine-workers the value of their labor-power and still make a profit?

Would it be possible for the mine owners to pay the mineworkers MORE than the value of their labor-power and to sell the coal at less than its value, and still make a profit? Explain why this would be possible.

If the wage-workers should become strong enough to demand the value of their products what would happen? Would there be any surplus left for the capitalist class? Explain why not.

What becomes of the difference between the value of your labor-power and the value of the things you produce in the factory or mine? Suppose you are working in a California mine and earning $3.00 a day, which is sufficient to buy food, clothing and shelter IN CALIFORNIA, enough to produce your labor-power. Suppose your employer wants to send you, and some of your California comrades to work in his mines in Alaska. The value of the necessities of life are far more in Alaska than they are in California. It requires $6.00 a day to buy food, clothing and shelter (to produce LABOR-POWER) in Alaska.

Will you be able to save any more money in Alaska at $6.00 a day than you would in California at $3.00 a day? Why not? Who pays the difference in the high prices of the necessities of life? YOU or YOUR BOSS? (We are not speaking of individual cases, but of high prices charged for food, etc., in general.)

Of course, we all know that the working class produce all exchange value. We make all commodities, but as we have sold our labor-power to the boss, our products belong to HIM. So the boss pays for nearly everything, because he has appropriated the things we have made.

When the value of the necessities of life RISE, does the working class or the capitalist CLASS pay the bill? In the case of our mining jobs in Alaska, do WE pay $6.00 for our board, clothes and room, or does the $3.00 increase in OUR cost of living FALL ON THE CAPITALIST?

We know that strength to work, or labor-power, is a commodity. The value of a commodity is determined by the necessary social labor time contained in it.

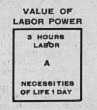

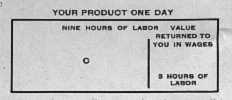

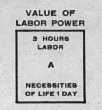

If it takes three hours of social labor to produce the necessities of life for you one day, the value of your labor-power one day will be three hours of necessary social labor.

Figure A will represent the value of your labor-power, because 3 hours of social labor are contained in the necessities of life which will support you one day.

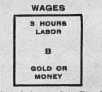

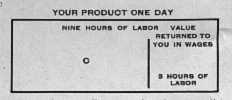

Let Figure C represent your product for one day. It contains 9 hours of labor time. The capitalist who employs you will need to return to you sufficient value to enable you to pay for A (or the cost of living).

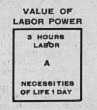

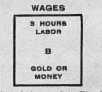

Figure B is equal to A because it contains 3 hours of labor. It represents the value returned to you by the boss in the shape of gold or wages.

We know that A is equal to B. And we know that C contains three times the value of a or B. We know also that the capitalist is constantly trying to prolong C into ten or even eleven hours, and that capitalists cut wages whenever and wherever possible. It is only by constant struggle that the

working class has been able to maintain its position, to secure a, perhaps normal, increase in wages, or a shorter workday.

It is self-evident that if you secure more wages (B) there will be less of the value of your product (C) remaining for the capitalist employing you, just as a reduction in wages leaves more surplus value for him.

An increase in the length of your workday (C) to ten hours will leave 7 hours of unpaid labor instead of six. A shorter workday will leave less surplus value for the capitalist.

Reformers believe that if we could decrease the cost of living we would better our condition. They think if A (the cost of living) were lowered, we could save a part of our wages (B). Of course, the value of our labor-power falls with a decrease in the value of the necessities of life, but they imagine we might be able to lower the cost of living without suffering a corresponding decrease in wages.

Personally, you know if your landlord should cut your rent down one-half next month, you would have more money left to spend for other things. Personally, you know if your brother offered to board you at half the regular rate, you could save a still larger sum of money next month. This is true of your individual case.

But we are not talking about individual cases, though we use concrete examples for the sake of making things clear. We are asking if low prices would benefit the wage-working class.

We will suppose an extreme example in order to illustrate our explanation. Suppose the City of Chicago should buy up all the houses, flats and cottages that rent to the working class here, and suppose this city should cut rents down one-half. Suppose that Chicago had municipal ownership and it was possible for the city to reduce the cost of living here 50 per cent. What we want to consider is–would the reduction benefit the working class or that part of capitalist class not directly engaged in producing the necessities of life?

When the cost of living is greatly reduced at any given city, workingmen and women flock to that point to sell their labor-power. They believe that if they can get jobs where it costs less to live, th~y will be able to save money and, perhaps, finally climb into the capitalist class themselves.

But note what happens. There is an immediate influx of workers into the city of low prices. The competition among workers for jobs becomes more keen at once, and it is always keen. Capitalists purchase labor-power at the lowest price. Men and women offer to sell their labor-power at a lower and still lower price till wages again fall to the cost of living. In a very short time these workers will find that they have gained nothing.

Take the examples of A, B and C. When the cost of living (A) is cut in half, the competition, among the, sellers of labor-power, reduces wages (B) accordingly. If your capitalist employer is a steel manufacturer will he be able to appropriate more or less of the value of your product?

Capitalists rarely start industrial enterprises in Alaska because the cost of living (or value of labor-power) is so extremely high in the far north that there is very little surplus value left for them.

The value of a commodity is determined by the average social labor contained in it. The Alaska steel manufacturer would have to compete in a world market just as the Bethlehem and Gary mills compete, and it is necessary social labor only that makes value.

Reports are coming from Guatemala of cotton manufacturers who are locating and establishing cotton mills there. The natives of Central America can live on very low wages. Almost all natives in Guatemala build and own their own thatched huts, The climate is warm and artificial heat is never needed. Nobody requires steam heat or base-burners. A cotton shirt and cotton trousers clothe a man as well as his neighbors, so that the cost of living is a very negligible quantity. Bread fruit and bananas grow wild, and 10 or 12 cents a day will keep a native in comfort, a recent magazine article, which dwelt upon the advantages of capital in Central America reports that Guatemala natives receive, on the average, 9, 10 or 12 cents a day.

If the Central American natives were driven to toil as fiercely as we are of the states, Guatemala would be a heaven for capitalists. But it is still possible for them to live without much labor. When, however, the capitalists gain control of the land, so that the natives will be forced to sell their labor-power in order to live, more exploiters of labor will turn toward the land where the cost of living is almost nothing (labor-power of little value), and where they will be able to appropriate a still larger portion of unpaid labor.

From no angle can we find where low prices will benefit the working class for any appreciable length of time, because the struggle for jobs soon brings wages down to just about enough to live on.

The workingmen and women of Belgium have long labored to reduce the cost of living in Belgium. They have formed co-operatives and we learn that they actually HAVE been able to lower the prices on the necessities of life. If we had list prices of groceries in Belgium, we would probably be amazed at the difference in their prices and ours. And still only recently a Belgian Socialist wrote us that his country was still the Heaven for capitalists and the hell for workingmen and women.

Will wages in Belgium be as high as they are in Colorado or in Ohio? Why not? Are the Belgium comrades any better off than we are?

If every workingman owned his own home in Salt Lake City, would this tend to INCREASE or to DECREASE wages there? Explain why.

Why do the owners of factories usually build them in small towns? Why are there so few factories in New York and Chicago?

Is the wage-worker exploited of his product at the mine or factory or is he CHEATED when he spends his wages for the necessities of life?

Before you reply to the above question, reply to the following:

What determines the value of your labor-power? What determines the value of any commodity?

Does A (the cost of living) have anything to do with the amount of B (wages) you will receive?

If B (wages) are not equal in value to A (the cost of living) will this mean that you HAVE NOT RECEIVED the value of your

labor-power, or will it mean that the grocer, and butcher, and clothier are cheating you?

If wages (B) are reduced will your employer be able to appropriate more surplus value?

Owing to the improved methods of production the necessities of life are slowly decreasing in value. A contains less labor; is less valuable. Gold also is decreasing in value, contains less social labor.

What would be the natural explanation of the fact that gold today exchanges for FEWER commodities than it did five years ago? Which would you expect to have decreased most in value–gold or the necessities of life?

If the necessities of life decreased FASTER than the value of gold decreased, would prices of the necessities fall? In this case B would be of more value than A. Would wages continue to be of more value than A for very long?

Would general co-operatives for reducing the cost of living in America benefit the working class? Or would they tend to reduce wages? Why?

Will we have to exclude the natives of Central America from the United States in order to prevent them from competing with us to sell their labor-power? Or are they already taking jobs from American cotton workers even though working in Guatemala? Explain.

We have been considering Low Prices and their effect upon the working class. We discovered that, owing to the competition among wage-workers for jobs, wages are reduced (when prices fall) to just about the cost of living. In discussing Low Prices we have learned what would happen to B, (wages) as a result.

We are still speaking of commodities which exchange at their values.

If A (Or the value of the necessities of life) is doubled, the value of your labor-power will also be doubled, Suppose A is doubled without B being increased accordingly–the value of food, clothing and shelter be twice what it was formerly and wages remain stationary. Reformers will tell you that the grocer, the butcher, clothier and landlord are exploiting you.

They say that your employer exploits you, but that when you go to spend your wages these other men also cheat or rob you.

But if wages (B) do not rise to the same level as the necessities of life (A) this merely means that your boss is no longer paying you the value of your labor-power. The value of food, clothing and shelter determine the value of your labor-power.

Do not be confused into thinking because rents are "high," or because food is expensive that you are exploited when you pay' for these things. As A increases in value your labor-power increases in value. And only when wages equal the cost of living are you receiving the value of your labor-power.

Shortage of workingmen may cause labor-power to exchange above its value temporarily; shortage or an over supply of any commodity may cause it to exchange above or below its value for a short time. But monopoly alone can cause a commodity to exchange above its value for any length of time. To repeat:

Reformer says: The wage worker receives his wages. That he is exploited by his employer. But when he goes to buy shoes, food, meat or clothes, he finds the owner of these commodities selling them at a higher price than he can pay. Then the reformers conclude that these merchants are exploiting the workers also. These people do not understand that the value of A (the necessities of life) determine wages.

Not all individual workingmen or women receive the value of their labor-power. Some men and women receive a little more than the value of labor-power. We know a young girl in this city who works in a department store for $5.00 a week. She cannot buy food, clothing and shelter for $5.00. Her brother receives $18.00 a week. He can live on less than that sum. He helps his sister pay her expenses. Thus both receive the value of their labor-power.

Men cannot work long upon less wages than the value of their labor-power. They must have help from without. Fortunate members of families help those who do not earn enough to live on. Thousands of families receive intermittent aid from charity organizations, so that the working class, in general, receives just about the value of its labor-power. In other words, the army, of workers receive enough to produce more workers for tomorrow and twenty years from now. It is the unemployed fighting for jobs who force wages down almost to the bare cost of living.

We see how an increase in the value of A means a consequent increase in the value of labor-power. We must not, therefore, berate the grocer, the butcher or landlord when our employers fail to pay us the value of our labor-power. We will be forced to demand higher wages in order to live.

But High Prices do not necessarily mean that food, clothing, etc., have increased in value. It may mean that gold–or the medium of exchange–has decreased in value.

The tendency of almost all commodities is to decrease in value, as modern production lessens the necessary labor contained in them. Gold may decrease in value faster than the value of meat, shoes, bread and clothing has decreased.

A is shrinking, but B (wages) are shrinking faster in value. Since gold (or wages) is outdecreasing the necessities of life, in value, it exchanges for fewer of them. One dollar buys less meat today than it bought five years ago.

Reformers are crying for Low Prices, but revolutionists are demanding Higher Wages (the value of their labor-power) in all the gold standard countries today. They are also working for the abolition of wage-slavery tomorrow. Everywhere we see wages slowly rising to meet the increased cost of living.

We have bewailed the High Prices, while prices are only nominally higher than they were five years ago. Gold (or wages) has decreased in value considerably and as commodities tend to exchange at their values, gold buys fewer commodities.

We may still be receiving the same number of dollars each week, but the value of these dollars has decreased. Actually our wages have been reduced. Unless they enable us to buy the necessities of life we are not receiving the value of our labor-power from our employers.

1. An increase in the prices of the necessities of life may come from an increase in the value of commodities. We shall have to receive an equal rise in wages if we are to get the value of our labor-power.

2. Wages (or gold) may decrease in value until they no longer will purchase A. Unless we receive more wages accordingly we will be receiving less than the value of our labor-power.

Now all through the preceding chapters I could hear, in imagination, the reformers crying, "But what about monopoly prices?"

In the first place, there never was an absolute, permanent monopoly. There are steel mills in China, Japan, Mexico, England and Germany which will supply the American market if they can undersell the home product. China is now shipping steel rails into California at a lower price than the American mills supply them.

There are still many independent oil companies in many lands. Automobile service, electric car lines, aeroplanes, water courses, chutes and flumes all infringe upon the railroads. Whenever the railway charges become more than the traffic will bear the manufacturer removes to another city.

Men may hope to gain permanent complete monopolies, but there is always the danger of somebody coming forth with a substitute. Some one is always providing substitutes.

No man was ever able to raise the general price of a commodity at will, and get that price. If any man ever held such power, he would have charged an unlimited price for his commodity and immediately assumed the world's dictatorship.

John D. Rockefeller may be able to raise the price on oil in certain communities but he cannot force men to buy at this price. So-called monopolists are subject to economic laws just as are wageworkers. No monopolist was ever so great a philanthropist that he did not charge all the traffic would bear at all times. We see, therefore, that they cannot raise prices at their own sweet will.

No man ever held a near monopoly but what other capitalists with money to invest turned ever longing eyes upon the Golden Goose ready to produce a substitute that will relegate his rival's product to the Past.

But there are some very near monopolies in the United States. Some of these doubtless are able to sell–or exchange–their commodities above their value. A few of these are engaged in the production of food, clothing or houses.

Now it does not mean because a monopolist holds temporary control of a commodity that he will raise the price of that commodity. He will surely seek to lower its value by closing down unnecessary factories and installing improved machinery that will lessen the labor contained in his product. Many "monopoly" owned commodities sell at a lower price than they did before they were monopoly produced.

If a monopoly produced commodity exchanges at its value, under the new method of production, its prices would be lower. Many friends assure me that oil is much cheaper today than it was twenty or thirty years ago, before John D. began to build the Octopus. If a monopolist continues to sell a commodity at the same price it exchanged for formerly, he will be able to appropriate greatly increased profits, for its value will have decreased–perhaps 50 per cent.

But we will take an extreme case to illustrate who pays the increased price where an imaginary Octopus doubles the price of the necessities of life.

Let us suppose that 500 miners are receiving $5 a day working a copper mine in Alaska. Five dollars just affords them a comfortable or tolerable living in Alaska. The man who owns the food and clothing supply in Alaska at this time has a temporary monopoly–an absolute, temporary monopoly of these necessities.

This man finds he actually can double the prices on these necessities for one season. The cost of living in Alaska rises to $10.00 a day.

The employer of the miners will be obliged to double their wages if the miners are to receive the value of their labor-power as formerly. He will need to pay $10.00 a day if he expects to have them to work for him tomorrow. If the mine owner finds $10.00 in wages will leave no profits for him, he will refuse the increase and shut down the mine; the miners will return South and the Monopolist will find himself without a market. The possibility of such a contingency has always to be reckoned with by every "monopolist." There is always the danger of killing the Goose that Lays the Golden Egg.

You see how if the price of A is doubled, wages will need to follow, and as B (wages) are increased there remains less surplus value for the employer to appropriate.

The monopolist, in this case, who has been able to double the price on the necessities of life and cause our wages to be doubled will have forced our mine-owning employer to divide this surplus value with him.

Note figure C. If the portion returned to us in wages is doubled, there will be just that much less unpaid labor for our employers to keep. The extra portion paid to us will be paid over to the monopolist.

Monopoly generally means that the monopolist is strong enough to force other employers to divide with him a portion of the value of our products formerly appropriated by them.

The real fight is between the monopolist and the mine-owning employer who will do all in his power to "smash the Trusts."

The mine owner in this instance may offer us $9.00 a day and we may try to live on $9.00 for a few weeks. We will be unable to do it because we will be receiving less than the value of our labor-power.

Do the Trusts rob the wage-workers when selling them Trust made products?

Can a monopoly sell its product at the same price as the independent concern and make a bigger per cent of profit? Why?

What are three causes for a rise in Prices? Explain.

There are more factories producing barrels this year than last year. All these owners are competing with each other to sell hoops and staves. But the prices of hoops and staves have risen everywhere, Why? Has the value increased? Precisely the same methods of production prevail in the hoop and stave industry as formerly.

Also the wages of men and women working in the hundreds of small factories all over the United States have risen during the past year or two. There are many men and women out of employment, but they have not reduced wages at these points by competing for jobs, although they are always in the market offering to sell their labor-power. Even men out of work are asking MORE for their labor-power than they asked a few years ago.

Why are wages rising at these points and everywhere in general? Why are men who are out of work asking more for their labor-power?

There are no Trusts in China–yet. Prices of the necessities of life are extremely low, Do "low prices" in a country necessarily mean the working class is any better off than where "high prices" prevail?

Suppose one landlord owned all the ground and cottages rented to workingmen in one city. Suppose all these men worked in a factory at this point. Suppose the landlord raised the rent on cottages from $10 to $30. If the workmen had been receiving just about the value of their labor-power before, what would happen when rents were raised? Who would actually pay the increase?

There are several ways whereby wage-workers may try to improve their condition today. In Lesson V, we discussed Low Prices and their effect upon the condition of working class life. We discovered that as the prices on the necessities of life fall, wages fall proportionately because of the competition among wage-workers for jobs.

It would be impossible for an employer of labor to arbitrarily lower wages, just as it is impossible for capitalists to arbitrarily raise the prices on commodities. The conditions must be favorable to such a rise or fall in prices. It is the Army of Unemployed men and women that force wages (or the price of labor-power) down when the cost of living falls. We were unable to find where low prices would benefit the working class.

In discussing prices in the last two lessons, we have not said much about wages, or the price of labor-power. Labor-power is a commodity just as 'stoves, coats or flour are commodities. And the value and price of labor-power are determined exactly as the price and value of all other commodities are determined.

Wage-workers are always trying to get higher wages, or a better price for their labor-power.

It is easy to understand that the gold miner who secures a raise in wages from $2.00 to $3.00 a day, leaves less surplus value for the mine-owner. He receives back more of his product. And the aim of Socialists or revolutionary workmen arid women is to become owners of their entire product.

Confused economists have repeatedly claimed that a rise in wages was no benefit to the proletariat. They insisted that the capitalists would raise prices on the necessities of life, so that the workers would be just where they were before.

But in Value, Price and Profit, chapter II., page 17, Marx says: "How could that rise of wages affect the prices of commodities? Only by affecting the actual proportion between the demand for, and the supply of, these commodities."

"It is perfectly true, that, considered as a whole, the working class spends, and must spend, its income upon necessaries. A general rise in the rate of wages would, therefore, produce a rise in the demand for, and consequently (temporarily) in the market prices of, necessaries.

"The capitalists who produce these necessaries would be compensated for the risen wages by the rising market prices of the commodities."

Note, Marx says that temporarily the prices on necessaries would probably rise, owing to the increased demand for food, clothing and better houses; not because the capitalists decided to raise prices. And then note what begins to follow immediately:

"What would be the position of those capitalists who do not produce necessaries? For the fall in the rate of profit, consequent upon the general rise in the price of wages, they could not compensate themselves by a rise in the price of their commodities, because the demand for their commodities would not have increased...

"Consequent upon this diminished demand, the prices of their commodities would fall. In these branches of industry, therefore, the rate of profit would fall....

"What would be the consequence of this difference in the rates of profit for capitals employed in the different branches of industry? Why, the consequences that generally obtains whenever, from whatever reason, the average rate of profit comes to differ in the different spheres of production.

"Capital and labor would be transferred from the less remunerative to the more remunerative branches; and this process of transfer would go on until the supply in the one department of industry would have risen proportionately to the increased demand, and would have sunk in the other departments according to the decreased demand.

"This change effected, the general rate of profit would again be equalized in the different branches. As the whole derangament originally arose from a mere change in the proportion of the demand for, and supply of, different commodities, the cause ceasing, the effect would cease and prices would return to their former level and equilibrium.

"The general rise in the rate of wages would, therefore, after a temporary disturbance of market prices, only result in a general fall in the rate of profit, without any permanent change in the prices Of commodities."

We will use a concrete illustration to explain Marx's point. In a mining camp the miners secured a gain of wages of from $2.00 to $3.00 a day. The man who ran the only restaurant in the camp thought he could raise the price of board from $4.00 to $5.00 a week. For a week or two the miners paid the advanced price, but the third week a new restaurant was opened by a man who heard of the "prosperity" in this, particular camp, and inside of two months there were four restaurants competing for trade in Golden Gulch. This competition among the restaurant keepers forced board down to $3.00 a week. Some of them moved away until board fell to the average rate of board in that state.

As long as prices were better there new investors came to Golden Gulch, and when they fell below the average price for board investors went away.

Marx says that when workmen and women get higher wages, they spend this increase in better food, better homes and better clothing. This stimulates the demand for food, clothing and houses. More capitalists begin to invest in food production, in houses and in the manufacture of clothing. The competition among capitalists often brings the prices on these things below the rates charged before the workers received their increase, until these capitalists find they can make more money in other fields, when they invest in other industries and prices fall to what they were before the rise in wages.

On the very last page of Value, Price and Profit, Marx says again:

"A general rise in the rate of wages would result in a fall of the general rate of profit, but, broadly speaking, not affect the prices of commodities."

If you were getting three dollars a day for digging gold out of a mine and you secured $4.00 by striking, would there be as much surplus value left for your Boss as before?

On what do wage-workers usually spend their money? On

luxuries?

If the working CLASS is able to force up wages two dollars a week for every man and woman, will they spend the increase on automobiles, trips to Europe, or upon more and better clothing and food?

What happens when there is a sudden increased demand for a commodity? Does the price of this commodity rise or fall (temporarily)? If the capitalist producing this commodity, for which there is a suddenly increased demand, is able to get higher prices for it, will this attract other capitalists into the same field of production in the hope of securing bigger profits?

What happens when several big capitalists fight for a field of production where prices are high? Do prices fall?

Do these capitalists remain producing a commodity after its price falls so low that they cannot make the average rate of profit?

When they go into another sphere of production do pricer an this commodity fall to normal again?

Why cannot a capitalist raise prices at his own will? Suppose a wealthy ranch owner has a splendid stock of horses when the U. S. troops are sent down to the Mexican borderline. Horses are very scarce, since automobiles have won favor with the leisure class. He sells these horses at an enormous price. There is still talk of war. What does every other ranchman in the country plan to do when he hears of the profits of the lucky owner of the horses? Do they an go into the COAL BUSINESS?

EVEN if there is still war, or rumor of war, will the price on horses be as high in a few years as it is now? Why not?

In Lesson VII. we discussed a general increase in wages, and how and why they would benefit the working class. We discovered that a general increase in wages mould ultimately result in a fall in the average rate of profit, but would not affect prices in general.

But now that we have seen the desirability of higher wages, how may we secure them?

It is true that the working class, as a class, has never been sufficiently well organized to demand a universally higher price for its labor power–a larger portion of the value of its product from the capitalist class.

It is equally true that when they shall have become sufficiently organized and class conscious to do so, they will not stop with asking higher wages, but will abolish the whole wage system itself.

But Capital makes continual war upon the workers. It reduces wages to the bare cost of living and lowers the standard of living whenever and wherever possible. It prolongs the hours of labor as far as the physical endurance of the workers themselves will allow. And the workers find themselves forced constantly to fight in order to hold the little they already have. So that, on every side, we see little groups of workers in conflict with their employers, fighting to maintain working conditions, or to improve them where they become unendurable.

It is obvious, that men or women working from ten to sixteen hours daily will have little strength or leisure for study, or activity in revolutionary work. It is also patent that wages are bound to be higher where men toil eight hours a day than where they work sixteen hours. It requires two shifts of men, working eight hours daily, to run a machine that one man runs sixteen hours.

It is not only necessary, but it is a highly desirable matter, that we continue to resist and to advance and attack in our daily struggle with the capitalists; For it is through present defeats and victories that we learn our strength and our weaknesses. We learn to fight by fighting. New tactics are often evolved in struggles that seem to be total failures. And class solidarity becomes a living thing, a resistless weapon, when we are fighting and acting more or less as a class.

Even group struggles–the isolated wars waged by craft unions against their employers–hear fruitful lessons in class solidarity. For craft wars, are becoming more uniformly failures, and to show the vital need for a wider and even broader organization of the workers of the world.

But craft union struggles have not always failed in that which they set out to accomplish, although victories are becoming increasingly difficult and impossible with the advance of productive machinery that abolishes the need of skilled laborers. Skilled workers have often been able to form skilled labor monopolies, or unions, where their particular skill has been in demand, and have forced their employers to give them shorter hours, higher wages or better working conditions. But these victories have been due to a monopoly of a particular kind of skill, and not at all to any class consciousness on the part of the workers.

Just at present workers all over the world in the countries where gold is the recognized standard of value are demanding, and generally securing, higher wages. This is owing to the decreasing value of gold, which exchanges for fewer commodities than formerly, and which has consequently caused a rise in prices, and an increase in the cost of living.

These workers are gaining higher wages; from the employing capitalists because it costs more to "keep" them, just as the man owning a horse has to pay a bigger bill when the price of "feed" goes up, if he wants to keep the horse. They are not gaining higher wages through class conscious efforts, although every struggle is a breeder of class consciousness, even though it be only in a negative way.

Modern machinery is eliminating the need of skilled labor and unskilled labor with ever increasing speed. Skilled workers are thrown into the ranks of the unskilled and unskilled workers are thrown into the ranks of the unemployed. And gradually all workers are being more and more forced to compete with each other for jobs upon a common level. Nothing can stop the progress of the automatic machine, the most wonderful invention of man through all ages–the machine that will one day free mankind from ceaseless anxiety and degrading toil!

But struggle we must–today and tomorrow. And the fight will grow keener with the passing years.

Men and women are being hurled into the ranks of the unemployed by thousands and by hundreds of thousands. We must reduce the number of jobless workers.

We must organize along industrial lines to shorten the hours of labor. If an eight-hour day were inaugurated, it would mean the additional employment of millions of men and women in America tomorrow. It would insure us leisure for study and recreation-for work in the Army of the Revolution, and it would mean higher wages in america generally. For the fewer men there are competing for jobs, the higher the wage they are able to demand.

To repeat: Modern machinery is throwing more and more men and women into the Army of the Unemployed. Shorter hours will employ more men and women, and will maintain and even increase wages, to say nothing of the tremendous development of the fighting spirit, the solidarity and class consciousness of the workers.

Flood the nations with your ballots, workingmen and women of the world. Elect your shop mates, your companions of the mines, your mill hand friends, to every possible office. Put yourselves or your co-workers into every government position as fast as possible to render your court decisions, to hold in readiness your army; to control your arsenals and to protect you with your constabulary, to make your laws and to serve your fellow workers, whenever and wherever and however possible.

And organize industrially. With your government at your backs, ready to ward off Capitalism, ready at all times to throw itself into battle for you, you can gather the workers of the world into your industrial organization and sign the death warrant of Wage Slavery!

Which is the most benefit to the working class, a rise in wages or shorter hours? What is the greatest hindrance to the workers securing higher wages? Or better conditions of any kind?

What would be the effect of a general shortening of the hours of labor in one nation? Do shorter hours tend to increase or decrease wages? Why?

If the general workday were suddenly to be lengthened three hours a day, what would be the effect upon unemployment? Would this tend to reduce or increase wages? Explain why shorter hours tend to increase wages.

When you seek a job you meet your boss as the seller of a commodity. What is the commodity? What determines the price (or wages) you will get for your labor power? What determines the value of this commodity?

What determines the price of any commodity? What determines the VALUE of a commodity. Do supply and demand affect the value of a commodity? Do they affect the PRICE of a commodity?

Suppose it takes ten men twenty hours to make 100 pairs of shoes in one factory and ten men one hundred hours to make 100 pairs of shoes in another factory. What would determine the value of a pair of shoes? The labor contained in the shoes produced in the first mentioned factory or in the second factory? Or the AVERAGE labor time necessary to produce a pair of shoes?

The working class generally receives the value of its labor power. But it does not receive the value of its PRODUCT. Explain the difference between these two.

Where do the profits come from? What is surplus value? Who appropriates it? Can an employer of labor pay his workmen the value of their labor power and sell their product at its value, and still make a profit? Would it ever be possible for him to pay the laborers MORE than the value of their labor power and to sell their products at LESS than their value, and still make a profit? Explain why this would be possible.

Are the workers any better off where the cost of living is low than where the cost of living is high? Are they able to save any more in the countries of low prices? Do low prices benefit the working class? Do we find wages high or low where the cost of living is high? Where the cost of living is low? Does a low cost of living benefit the capitalists? Why?

Do your butcher and your baker and your landlord exploit you? Suppose all three classes of men were suddenly able to double prices in America, would you pay the additional bills or WOULD THE EMPLOYING CAPITALISTS pay them? Would wages rise?

Suppose wages did NOT rise, would you then be getting the value of your labor power? If you failed to get higher wages, would this mean that the landlord and butcher and baker exploit you, or would it mean that you had to have more wages, if you were to continue to receive the value of your labor power?

What is the great aim of Socialism?