That the passing of Grace Lee Boggs, a remarkable Chinese American author, activist and humanist philosopher should merit a statement of condolence from President Barack Obama was quite fitting. Grace had been an inspiring and courageous organiser for the Civil Rights and Black Power movement in the US and had worked alongside Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and Rosa Parks.

In 2008 she championed Obama for “providing the authentic, visionary leadership we need in this period,” even comparing him to Martin Luther King, and so it was only right that Obama returned the compliment.

Yet if someone had told the young Grace that after her passing she would receive praise from the White House, she would have been incredulous. For what Obama’s statement neglected to mention was that during the 1940s and 1950s Grace had been a revolutionary socialist who, working in collaboration with figures such as CLR James and Raya Dunayevskaya, made important contributions to Marxist theory.

In 1942, in an article for the Trotskyist journal New International, she had explicitly warned that black Americans “must be wary of regarding every man of their own race, especially those whom the ruling class favours by appointment, as having more than the most superficial colour identity with them... The government knows the usefulness of Negro administrators to help it maintain its oppressive rule... Whether Negroes take their orders directly from the white Jim Crow ruling class or from the coloured henchmen or colleagues of this class, the Negro’s lot will remain the same under the existing social order.”

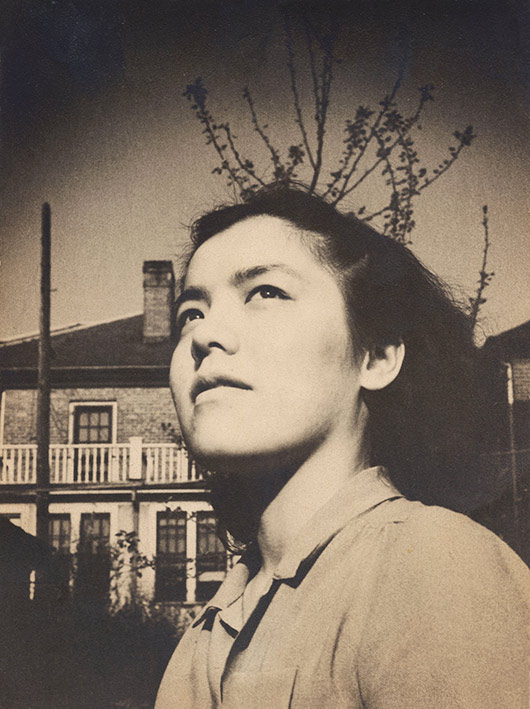

Grace was born Yuk Ping or Jade Peace, Americanised to Grace Chin Lee, on 27 June 1915 above her father’s Chinese restaurant in downtown Providence, Rhode Island, one of seven children. After moving to New York when her father’s business expanded in the “Roaring Twenties,” Grace experienced something of the widespread racism against Chinese Americans.

Her intellect and talent for independent critical thinking saw her aged 16 decide to defy expectations and study philosophy at Barnard College, where she was one of only three students of colour. Amid the Great Depression, Grace later recalled that “what troubled me as an undergraduate major in philosophy was that my professors were an elite who saw themselves as ‘pure reason’ in search of Truth – having nothing to do with the world.”

Grace completed a PhD at Bryn Mawr College in 1940 on the American pragmatist philosopher George Herbert Mead, though her emerging intellectual passion was for reading Hegel in the original German. For her, “Hegel was like music.”

Her colour and gender meant Grace had no hope of securing anything but the most menial teaching post, so she moved to Chicago, where she came across the Trotskyist Workers’ Party agitating against poor housing conditions.

In 1941 black Americans were also on the march, and there was a tremendous response to a call by black trade union leader A Philip Randolph for a March on Washington which successfully forced President Roosevelt to end racist discrimination in the booming war-time defence industry.

As she recalled, “I was attracted to the black movement because Jim Crow in 1940 was so barbaric and because I viewed black struggle as the catalyst for revolutionising this country.” Grace had seen something of the power and potential of a mass movement from below for the first time, and “decided that what I wanted to do with the rest of my life was to become a movement activist in the black community.”

During the Second World War Grace worked alongside mainly black women workers in a defence plant in Brooklyn, New York. She was thrilled by the camaraderie among her fellow workers and helped organise black history classes in coffee breaks.

In 1941, through the Workers’ Party, Grace had had the fortune to meet the black Trinidadian Marxist CLR James, who stopped by Chicago on his way back from organising sharecroppers in south east Missouri.

When he found out I knew German and had studied Hegel, we sat down almost immediately on the red couch in my basement room and began comparing the texts of Marx’s Capital and Hegel’s Logic. That was the beginning of our close collaboration of 20 years.

Grace learnt her Marxism through joining James’s small current within US Trotskyism, known as the Johnson-Forest Tendency (from James’s and Dunayevskaya’s pseudonyms, “JR Johnson” and “Freddie Forest”).

Under her own pseudonym “Ria Stone” Grace soon emerged as a leading theorist of this group, and would later co-author several pioneering works of Marxist theory with James and Dunayevskaya, including The Invading Socialist Society and State Capitalism and World Revolution.

Grace was particularly convinced by James and Dunayevskaya’s Marxist analysis of the Soviet Union under Stalinist dictatorship as a form of state capitalism rather than any form of socialism. As she recalled in an interview in 2000:

“Regardless of whether the state or private capitalists owned the means of production, Soviet workers in the process of production were still being exploited, dehumanised, and deprived of their ‘natural and acquired powers’ in the way described by Marx in Capital.

I was attracted to the state capitalist position on the Soviet Union because it seemed much more dialectical. It embodied much more the way of thinking of Hegel, whom I had studied, because it recognised that new contradictions could arise out of great struggles for liberation and that progress did not take place in a straight line. I was also rather attracted to it because it emphasised the humanity of the workers rather than property relationships.

When Dunayevskaya found a Russian translation of Marx’s 1844 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts in New York Public Library, Grace translated three of Marx’s essays from the original German into English, and in 1947 these were published by the Johnson-Forest Tendency, their first ever publication in English.

That year she also wrote an afterword to The American Worker, a detailed analysis of class struggle at the point of production written by a General Motors worker Phil Singer (under the pseudonym Paul Romano), which stressed the importance of Marx’s theory of alienation – developed in the 1844 Manuscripts – to understanding the dehumanisation which accompanies exploitation in the labour process.

In 1950 the Johnson-Forest Tendency broke with the official Trotskyist movement to form their own independent Marxist current, and in 1953 Grace moved to Detroit, finding work as an office worker in the local car plants. She soon married James Boggs, a member of the group and a militant at the local Chrysler-Jefferson car plant – an organic intellectual of the organised black working class. On their honeymoon in Alabama the couple had to sleep in their car because Southern motels refused to accept mixed-race couples.

The post-war economic boom, the development of new technology in factory production, the conservatism of the trade union bureaucracy and the lack of response from most white workers in the US to the growing Civil Rights movement led Grace and James Boggs to declare in 1961 that the US working class was “backward and bourgeoisified.” For them hope now lay in revolutions in the Third World and marginalised outsiders such as young black people.

This abandonment of Marxism’s stress on the centrality of the working class as the agent of change in society led the Boggses to politically split with CLR James in 1962. Grace’s subsequent tireless and heroic work as a local anti-racist organiser in Detroit nonetheless won her an audience among militants around the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit – and so confused the FBI that they thought she must be “Afro-Chinese.”

The defeats of the liberation movements which had reached their height in the late 1960s by the 1970s and 1980s now led James and Grace Boggs to shift even further away from Marxism towards what they called “dialectical humanism,” which sought to “advance beyond the idea that all radicals have held – that in order to advance socialism, you must first smash capitalism. We have to advance towards the new society by projecting an entirely different way to live and by building new social ties.”

In the face of the devastating de-industrialisation of Detroit, the one-time jewel of US industrial capitalism, James and Grace Boggs now saw the fight as not primarily one to save jobs and defend public services but to try and “re-civilise our society” through fostering “collective self-reliance,” “creating support networks to look out for each other and moving onto community gardens and greenhouses, community recycling projects, community repair shops, community day care networks, community mediation centres.”

Grace Lee Boggs did much to clarify the classical Marxist conception of the revolutionary and creative role of the working class at a time when Stalinism meant that for many people socialism had come to be seen merely as state ownership without revolutionary democracy or workers’ control. Even though she moved away from this she remained an eloquent moral critic of capitalism.

Moreover, her record of activism from the 1941 March on Washington against Jim Crow up to the Occupy movement in 2011 ensures that she will rightly be remembered and honoured. In the words of veteran American radical Dan Georgakas – co-author of the classic work on the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Detroit: I do mind dying – Grace Lee Boggs was “a long-time legendary figure in Detroit and in the black liberation movement.”

As that movement re-emerges to confront the systematic murderous racism of the US state and society under the banner #BlackLivesMatter it can learn much from her life and work.