First Published: The Call, Vol. 7, No. 34, September 4, 1978.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

This is the ninth in a series of articles by Call journalists who visited Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia) in April. They were the first Americans to visit that country since its liberation in 1975.

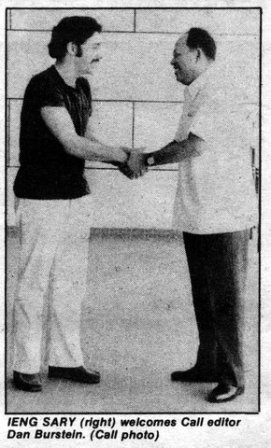

This week’s article–a continuation from last week–is based on an interview about the history of the Communist Party of Kampuchea given to The Call by Kampuchean Deputy Prime Minister Ieng Sary. Last week’s article covered the main events leading up to the founding of the CPK in I960. This week we examine the experiences of the Party between I960 and the CIA-inspired coup d’etat in 1970.

* * *

In February of 1963, Ieng Sary told us, the police assassinated the Secretary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK).

An emergency Second Congress of the CPK was held in the wake of the party leader’s assassination. Pol Pot, today’s Prime Minister, was elected Party secretary, a post he continued to hold through the revolution.

“After the Second Congress, we began to build up our forces in the countryside slowly and patiently,” said Sary, who himself went in 1963 to the first base area established in Ratanakiri Province. “We did a great deal of education among the cadres about the importance of serving the people, being self-sacrificing and maintaining discipline at all times. This communist education helped carry the Party members through very difficult times later on.”

Sary described some of his own experiences in those days, saying, “We were living in the forest and had no real food supply. We relied on the local tribesmen, who were minority nationalities and very tough fighters, to bring us food from the villages. Sometimes they would be captured by the enemy, though, and then we would have no food at all.

“We would have to live on bamboo that grew in the forest for a week or more at a time. But we always remained confident. We knew these tribesmen would never betray us. Even under torture they would tell the reactionaries nothing about our bases.”

“We also had a large united front movement,” said Sary. “But it took no organizational form. We just spread the ideas of uniting the people to fight for an independent, neutral and non-aligned Kampuchea. With these slogans we could unite with various forces among the petty-bourgeoisie, the intellectuals, the administration officials and the national capitalists.”

The Deputy Prime Minister went on to describe the different forces within the Kampuchean ruling class of that time, indicating three broad groupings. On the far right, there were those like Lon Nol who were completely reactionary and nothing but lackeys of foreign imperialism. In the center stood Sihanouk, the head of state, and some others like him who, while opposing communism, also supported a policy of genuine political independence for the country. On the left were progressive people like Khieu Samphan, today’s president of the State Presidium, who at that time was a well-known intellectual and politician. His stand against foreign imperialism was so firm that he was forced to flee Phnom Penh under intense pressure by the right wing.

“We mobilized both the middle and left sections of the ruling class,” said Sary, “and built a united front with them against foreign domination. We isolated the real traitors like Lon Nol.”

At the same time, Sary stressed, the CPK believed that the fundamental force in the united front had to be the workers and peasants.

“Although our Party was secret,” Sary commented, “the people knew that there was a “Khmer Rouge movement.’” [Sihanouk gave the CPK forces the name “Khmer Rouge,” meaning literally “red Kampucheans” in French–ed.]

“The people knew our Party was fighting for land, democratic rights and a better standard of living,” said Sary. “We educated the masses step-by-step about the role of the armed struggle, even though we had not yet established an army.”

During this period, the Party established what were known as “clandestine guards.” These units were made up of peasants secretly infiltrated into the government’s militia, which it had created to maintain law and order in the countryside.

With a wry smile, Sary noted, “When the landlords ordered these militia forces to attack the people, our men would refuse. The clandestine guards played an important role in defending our cadres and leaders and allowing our base areas to develop.”

Throughout the countryside in Kampuchea, the peasants were waging spontaneous struggles, especially as Lon Nol’s wing of the ruling class seized more and more power from Sihanouk, tightening the economic squeeze on the peasants.

Worried by the developing rebellion among the peasants, Lon Nol decided to build his own phony “peasant movement.” He did this with the intention of misdirecting the peasant struggle as well as of building a peasant 5ase to undermine Sihanouk’s control of the government. He would give orders to his agents in the peasant movement to incite incidents and then tell Sihanouk that this was the work of the “communists” in an effort to keep a united front between the CPK and Sihanouk from developing.

In 1967, a peasant rebellion broke out in the northwest town of Samlaut. Hundreds of armed peasants went up into the mountains, seizing land and rice. Although the CPK knew that the conditions were not yet right for unfolding armed struggle nationwide, the party nonetheless supported the just demands of the Samlaut peasants.

When officials came to negotiate with the peasants, the CPK urged that the government remove Lon Nol as Prime Minister as a political condition before ending their rebellion. Sihanouk agreed to the demand, replacing Lon Nol with the patriotic prince. Penn Nouth.

But Lon Nol’s agents were right inside the peasant movement. Coming down from the mountains, these agents gave information about the activities of all the participants in the rebellion to In Tarn, then governor of Battambang Province. In a plot designed to abort the growing revolutionary movement, In Tarn connived with Lon Nol to make some concessions to some peasants who participated in the rebellion, while massacring all the communists and progressive forces.

“From June of 1967 on,” Ieng Sary recalled, “the Party began to lay plans to organize an army. We knew that Lon Nol would eventually try to stage a coup d’etat. We had to get prepared for that situation.”

In January of 1968, the Revolutionary Army was beginning to take shape. On January 17, a successful uprising led by the Party was staged at Bai Baram, near Battambane. In this battle the guerrillas captured their first weapons.

“On February 25,” said Sary, “the Central Committee issued a circular calling for insurrections all over the country. Even though it was a very difficult situation for us with hardly any weapons, no doctors and no medicine, we knew that our line was correct. And so we were able to inspire the people to fight.”

The CPK also knew that as the contradictions inside the country heightened as a result of the revolutionary war they were waging, the unity of the ruling class would break up as well. Recognizing that Sihanouk was a potential ally, the CPK and the Revolutionary Army made it clear in all their actions that they were fighting primarily the right-wing militarists and not Sihanouk, even though Sihanouk went along with many of the militarists’ repressive sweeps.

In one such attack, the government army sent 10,000 troops against the guerrillas in Ratanakiri. The assault was personally led by Lon Nol, who had once again entered the government as Chief of Defense.

“It was not just 10,000 troops they sent against us,” Ieng Sary remembered, ”but also armoured cars, planes and artillery. Even with all this firepower, they couldn’t knock us out. Winning this battle gave us great confidence.”

By the end of 1969, it was becoming obvious that Sihanouk’s neutralist stance could not be tolerated much longer by the U.S. imperialists, who were seeking to use Cambodia as a base for attack against Vietnam. Lon Nol. on the other hand, was perfectly willing to let the U.S. use Cambodia as a staging area against Vietnam. That Lon Nol would come to power in a coup d’etat was for the CPK a foregone conclusion.

(to be continued)