Quebec 1837-1839

The Patriotes Rebellion

Source: L'Aurore des Canadas, February 19,1839. In Au Pied-du-Courant, edited by Georges Aubin. Nadeau & Comeau, Montreal, 2000.

Translated: for marxists.org by Mitch Abidor.

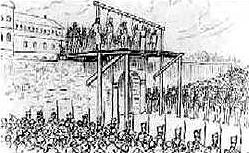

A contemporary account of the execution of the main Patriot leaders. The remains of the prison before which they were hung is now a museum in their honor.

As we had announced in our last publication, MM. Charles Hindelang, le Chevalier de Lorimier, Pierre-Rémi Narbonne, Francois Nicolas, and Amable Daunais were executed in front of the new prison.

They advanced with a firm step to the platform, from which their souls were to fly to a better world. Hindenlang, a handsome young man of 29, appeared first, with the same grace, the same assurance that he would have demonstrated in a salon. He went to the front of the scaffold and addressed a speech to the people that the newspapers of this city wouldn’t or couldn’t reproduce, doubtless because of the effect that it could have on the people. We, too, will abstain from publishing it. We will only repeat what the “Transcript” said, that “in dying he was still sure that the cause which he had joined was a good cause, that he denied the English government the right to put him to death, and he ended in crying out in a strong voice: VIVE LA LIBERTÉ!”

Like the other patients he had his hands tied behind his back, in such a way that he could only gesture with his head, which he nevertheless did with much grace. In finishing, he turned towards the political prisoners of the prison, who he'd asked to hold onto the windows, and made them a final sign of farewell.

De Lorimier, who constantly wrote and spoke, it is said, in the same way as Hindenlang, demonstrated the same intrepidity as his companions, but didn’t speak, nor did Daunais and Narbonne.

Nicolas gave a fairly long speech, where he deplored the errors of his life, recognizing that in death he was going to suffer God’s justice, who he'd often and seriously offended, recommended to parents that they watch over their children, and that the latter should listen to their parents and follow the precepts of religion. All those who were present who we have had the occasion to see are in agreement in saying that he made no allusion to the death of Chartrand, of which he was accused, nor of politics; that he only spoke of his errors in general.

After this speech, they conversed yet a bit with the different ministers of their religions and all showed great piety. At around 9:45 they placed themselves above the fatal trap and the executioner made his final preparations, after which the provost marshal, a sergeant of the army — who more or less filled the role of sheriff — gave the signal that was to put an end to their sufferings and their lives. Death was more or less instantaneous with Hindenlang and Nicolas; de Lorimier and Daunais seemed to suffer a short time. But the sufferings of Narbonne were long and horrible. Since one of his arms had been cut it hadn’t been possible to tie him up as well as the others; in his final convulsions he untied his hand, with which he seized objects around him and managed to move the cord from its true position. He even managed twice to reach a balustrade nearby and to put his feet on it, and was pushed away.

M. Duquet’s torture was accompanied by circumstances no less horrible. We hope that if justice is not yet satisfied and if there must be new executions this will be set about in such a way as to avoid such tortures to the victims.

De Lorimier and Hindenlang were men of much wit and talent. The former was a notaire in this city, was about 30 years old, husband and father of three children. In prison, both of them spoke almost with indifference of the death that awaited them. Hindenlang had left his body to Dr. Valée, asking him to bury it and send his heart to his mother in Paris in a jar of wine spirits. We are told that Dr. Valée wasn’t able to gather the body in order to fulfill the last wishes of the dying man. He wasn’t married and was a native of Paris where, it is said, he has a brother who works in commerce.

Nicolas was about 40 years old, a good-looking man who was nearly gigantic in size. He began as a merchant, and afterwards became a teacher. He had had a good education and wrote a pure French. He was from Quebec City and wasn’t married.

Narbonne as well was a good-looking man. He was a bailiff and widower, and he leaves behind two young children.

Daunais was a very young man, looking to be no more than 20 years old, a farmer, and the main support of an elderly and poor father.

In Au Pied-du-Courant his final words are reported as:

On this scaffold built by the men’s hands, I declare that I die with the conviction of having fulfilled my obligations with dignity. The sentence that struck me is unjust; I forgive those who bore it.

The cause for which I sacrifice myself is noble and great. I am proud of it. I don’t fear death. The blood that is spilled will be washed away with blood. Let the responsibility fall on those who deserve it.

Canadians, my final farewell is the old French cry:

VIVE LA LIBERTÉ!