Sc

Schaff, Adam (1913-2006)

Polish Marxist philosopher, born in Lvov, Poland, in 1913, studied Law and Econmics at the École des Sciences Politiques et Économique in Paris, and Philosophy in Poland.

Adam Schaff was the only Polish Marxist in the post-world war two period with an academic background. In 1945, he received a degree in philosophy at the University of Moscow and, on his return to Poland with the Red Army, and a month in the Polish underground as a member of the Central Committee of the Polish Workers Party, was given the first Polish chair in Marxist Philosophy at Warsaw University in 1948. In this position Schaff, and as a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, exerted his intellectual patronage in defence of Marxist orthodoxy and was considered to be the official ideologist of the Polish Communist Party, closely following the Moscow line. Schaff took a leading role in the ideological attacks on all the non-Marxist philosophical currents existing in Poland at the time. Schaff specialised in epistemology and his principal works include Concept and Word, Problems of the Marxist Theory of Truth.

After the death of Stalin in 1953, non-Marxist currents of philosophy Poland reasserted themselves, including the strong Polish tradition of studies in formal logic. In 1955, Schaff recognised that the source of the Marxist critique of formal logic was the ambiguous way in which it viewed contradiction: in Marxist classics contradiction simply expresses the fact that things and phenomena possess a “polar structure” that can be empirically identified, and the opposition between contrary forces and trends is the origin of movement and development. But contrariety, polarity, the opposition of forces or even the existence of two different aspects in an object are one thing; contradiction, as viewed by formal logic, is another. The confusion between contrariety and contradiction, he held, caused confusion on the part of the Marxists. This more tolerant attitude corresponded in the political sphere to the return to power of Gomulka in October, 1956, after a series of protests and strikes.

Polish Marxism then entered a new phase. 1956 was the year in which the so-called “Marxist Revisionism” gained strength: starting with an article by Kolakowski, its main representatives were Baczko and later Schaff, who proposed a “Marxist Humanism.”

Two different philosophical trends came to be formed in the Marxist environment: the “scientific” school and the “humanistic” school. For the former philosophy was knowledge of the world and thus epistemology and methodology, a science, based on specific sciences, whose concepts and methods it analysed using the tools of formal logic. For Marxists, this meant that its foundation was dialectical materialism, enriched with the methodological and logical progress made by contemporary epistemology. Marxism privileged the economic works of the mature Marx, Engels and Lenin, in order to throw light on their scientific nature and their agreement with scientific philosophy. This scientific Marxist trend, initiated by Krajewski, was heterogeneous: some saw it as mainly being based on the popularisation of Leninist and Stalinist ideas concerning dialectical materialism; others saw it as historical materialism, as a general interpretation of history, supplied by the leading role of the Communist Party; others tried to make Marxism more scientific by eliminating all its coarse, unacceptable elements and reconciling it with science, making it as rational as possible and in agreement with both common sense and the methodological requirements of contemporary epistemological (the Poznan School).

Schaff joined this more “humanistic” or “anthropological” school initiated by Kolakowski. This school thought that philosophy should deal above all with man and human action; it was therefore inspired by the tradition of classical German philosophy and other philosophical currents as well as phenomenology and existentialism. The aspects of Marxism privileged by this school were historical materialism and human action as the creator of knowledge in relation to social context. Although Hegelianism, existentialism and phenomenology were criticised, just as the former current had criticised neo-positivism, they appreciated its methods, which they opposed to the “positivism” of the “scientific school.” They obviously preferred the works of the younger Marx, along with those of Lukacs and Gramsci, and rediscovered authors such as Brzozowski.

Gomulka began to clamp down on this “revisionist” ferment and there was a mass purge in Poland in 1968, the year of the “Prague Spring,” and Marxists such as Kolakowski were dismissed.

The fall of Gomulka and the rise to power of Gierek in 1970 led to a gradual “de-ideologisation” of the system. The strength of the dissidents increased even more in the late ‘70s with the creation of the Workers’ Defence Committee (KOR) led by Jacek Kuron, which counted among its numbers eminent intellectuals, scientists, artists, priests and journalists. With the significant exception of the Poznan School, Marxism split up into a number of trends and positions linked to the personalities of individual scholars, increasingly independent of any orthodoxy and much more closely connected with European thought. Many thinkers embraced an anthropological interpretation of Marxism along the lines indicated by Schaff.

Schaff is currently a member of the Polish Academy of Sciences and a member of the Club of Rome.

Schäffe, Albert (1831-1903)

German sociologist and economist. Rejected the class struggle and called for class unity.

Scheflo, Olav (1883-1943)

A member of the Norwegian Labor Party from 1905, and a leader of the left opposition within the party. For a period, he edited the main newspaper of the Labour Party (while the party was still a member of the Comintern), and later he was editor of the CP’s main organ. After the October Revolution he played a very central role to convince the Labor Party to join the Communist International, and was a representative at the Second Congress of the Comintern in 1920 and a member of the Comintern Executive Committee from 1921 to 1927. Critical towards Stalinism, he left the Norwegian Communist Party in 1928 and rejoined the Norwegian Labor Party in 1929. As several other Left Oppositionists in the Communist parties in the late ’20s, he was branded as a “right-oppositionist.” In 1935, when Trotsky was in Norway, he strongly defended him against attacks from the Norwegian government as well as from the Stalinists. He was an ally of Jeanette Olsen, who also left the CP in 1928, and who later initiated the Trotskyist October group.

Scheidemann, Philipp (1865-1939)

Leader of the extreme Right wing section of German Social-Democracy, and an organiser of the suppression of the German working-class movement in 1918-21.

Schelling, Friedrich (1775-1854)

German philosopher, third of the "classical German idealists" after Kant and Fichte and a close friend of Hegel. Schelling sought to answer the question of how consciousness arises out of unconscious Nature and how "the subject" (objective knowledge as opposed to individual consciousness) could itself become an object of knowledge. Schelling offered a "philosophy of nature" and "transcendental idealism" in which he was eventually, explicitly led to the conclusion that only faith provides the necessary unity of subject and object for knowledge of truth. This later position is reflected in his History of Modern Philosophy.

At the age of 26, Schelling had succeeded Fichte as Professor of Philosophy at Jena after Fichte had been dismissed for atheism, and had published five books developing a new way out of Kant’s antimonies.

Schelling was by inclination more of a poet than a philosopher, but in contrast to Fichte he asserted the existence of the material world outside thought. As part of the circle of Romantic writers around Goethe, he maintained a lively interest in natural science, human history and culture generally. He did not see a resolution of the crisis of philosophy in dry categories of logic and thought. It was through a kind of aesthetic insight that human beings could know the world beyond thought, and it was in the practical activity of natural science and social or artistic creativity that antimonies were resolved.

Further, Schelling rejected any idea of a finished, closed logical system. Rather knowledge continuously brought forward new problems, new knowledge, new contradictions.

In 1841, Schelling played a key role in the Prussian government’s attack on Hegel’s philosophy and his young followers. See the essay 1841 and Engels’s record of Schelling’s speech attacking Hegel.

See Friedrich Schelling Archive.

Further Reading: Ilyenkov’s essay on Schelling and Plekhanov’s comment and the text of the major work of his earlier period, System of Transcendental Philosophy.

Scheu, Andreas 1844-1927

Born in Vienna 1844, died in Rapperswill, Switzerland 1927; model maker and gilder; one of the pioneers of the Austrian social democratic movement; associate of the anarchist Johann Most; member of the Association of Labour Education, Vienna, and the International Working Men’s Association; editor of Volkswille Vienna, correspondent for Gleichheit and the Arbeiter-Zeitung Vienna; representative at the Congress of the German social democrats in Eisenach 1869; arrested in 1870 on the accusation of high treason; emigrated to England in 1874, but stayed in contact with the Austrian movement; participated in the foundation of the Social Democratic Federation in England; present at the congresses of the Second International; moved in artists’ circles and wrote workers’ poems and lyrics.

Schiller, Friedrich von (1759-1805)

German poet, writer and philosopher of the Enlightenment.

Schippel, Max (1859-1947)

Right winger in the German social democracy.

Schlick, Moritz (1882-1936)

German Physicist and Logical Empiricist philosopher and leader of the European school of positivist philosophers known as the Vienna Circle; a precursor of the modern logical positivists, and an opponent of Conventionalism who also made early studies on the ethical implications of modern positivism.

After studying in physics at Heidelberg, Lausanne, and Berlin (under Max Planck), Schlick earned his PhD with his treatise, The Nature of Truth According to Modern Logic (1910). In 1922, he became Professor of the Philosophy of Inductive Sciences at Vienna.

The group of philosophers that gathered around Schlick at Vienna included Rudolf Carnap and Otto Neurath and the mathematicians and scientists Kurt Gödel, Philipp Frank, and Hans Hahn. Influenced by Schlick’s predecessors in the chair of philosophy in Vienna, Ernst Mach and Ludwig Boltzmann, the Circle also drew on the work of philosophers Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein. The members of the Circle were united by their hostility to what they called "metaphysics", by faith in the techniques of modern symbolic logic, and by belief that the future of philosophy lay in becoming the handmaiden of natural science.

As the reputation of the Circle grew, philosophers in other countries who were similarly inclined became familiar with one another’s work. Schlick directed the Circle’s activities and wrote for its review, Knowledge, until his death from gunshot wounds inflicted by a deranged student.

Schlick was a prolific essayist and author of a number of books on epistemology, natural philosophy and ethics. See Epistemology & Modern Physics.

Schlüter, Hermann

German Social-Democrat who after his expulsion from Dresden in 1883 conducted the publishing house of the Sozialdemokrat in Zürich. First organiser of the German Social-Democratic Archive. In 1889, he emigrated to America where he worked in the German workers’ movement. He wrote a history of Chartism and other studies of the English and American labour movement.

Schmidt, Konrad (1863-1932)

German economist and social democrat who corresponded with Engels.

Schober, Johannes (1874-1932)

The police official of the Hapsburg school, who became chancellor in September 1929 in the midst of the Austrian crisis, was police chief of Vienna from 1918, in which post he ordered firing on Communist demonstrations in 1919 and 1927. He was chancellor and foreign minister, 1921-22, 1929-30.

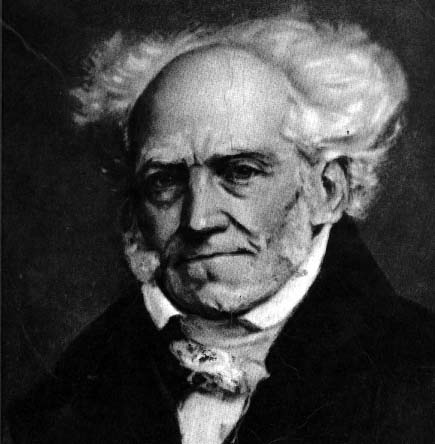

Schopenhauer, Arthur (1788-1860)

German philosopher, a product of the period of classical German philosophy (Kant, Fichte, Schelling, Hegel) who introduced elements from Eastern philosophy; the founder of Voluntarism and important precursor to Existentialism via his influence on Nietzsche and Freudian psychology; noted for his passionate hatred of Hegel, not able to publish until anti-Hegelianism became fashionable in the 1840s.

The son of a wealthy merchant who had moved to the free city of Hamburg, Schopenhauer was given a private business education. When his father died in 1805, his mother moved to Weimar, where she joined Goethe’s circle, Arthur joining her two years later, and in 1809 he entered the University of Göttingen to study medicine. Schopenhauer immediately transferred the humanities however, to study philosophy, and in 1813, he earned a PhD from the University of Jena.

Schopenhauer spent the following winter in Weimar with Goethe where he was introduced to the Hindu scriptures by the Orientalist Friedrich Majer. Schopenhauer would say that the Upanisads, together with Plato and Kant, constituted the foundation on which he erected his own system.

In 1814 Schopenhauer moved to Dresden where he completed a treatise On Vision and Colours in 1816, supporting Goethe’s views on natural philosophy.

His next three years were dedicated exclusively to the preparation and composition of his main work, The World as Will and Idea (1819), a series of reflections on the theory of knowledge and the philosophy of nature, aesthetics, and ethics.

The work argues that appearances may be comprehended, but only with the aid of constructs of the human intellect, and, with Kant, he argues that the “thing-in-itself” remains out of view for the intellect. The “thing-in-itself” however, is the Will, which is given to consciousness as one’s own Will. It is the Will which is responsible for the development of order in Nature and human society, but the Will brings with it only misery and pain.

The latter half of the book then deals with aesthetics and ethics, and points to the overcoming of the will as the means of liberation from suffering. Genuine liberation results only from breaking through the bounds of individuality imposed by the ego. Whoever feels acts of compassion, selflessness, and human kindness and feels the suffering of other beings as his own is on the way to the abnegation of the will to life and the asceticism which must be the aim.

Thus it can be seen that Schopenhauer’s system is a kind of amalgam of Classical German Philosophy with Eastern asceticism. The book marked the summit of Schopenhauer’s thought and in the years thereafter, no further development of his philosophy occurred. Meanwhile, his magnum opus remained almost unread.

In March 1820, after a lengthy tour of Italy and a dispute with Hegel, he qualified to lecture at the University of Berlin. Though he remained at the university for 24 semesters, only his first lecture was actually held, for he continued to schedule his lectures at the same hour when Hegel was lecturing to a large and ever-growing audience. Even his book received scant attention. In 1825, he made one last attempt to find a publisher in Berlin, but in vain. He renounced his career as a university professor and lived henceforth as a recluse, totally absorbed in his studies, especially in the natural sciences.

The second edition of The World as Will and Idea (1844) included an additional volume. Three publishers rejected the work, until an obscure Berlin bookseller accepted the manuscript without remuneration. However, Schopenhauer eventually achieved the recognition he desired and a third edition of The World as Will and Idea, containing an exultant preface, appeared in 1859 and, in 1860, a second edition of his Ethics. After Schopenhauer’s sudden and painless death, Julius Frauenstädt published his complete works in six volumes.

During this time, the actual impact and influence of Schopenhauer began to spread. By turning away from spirit and reason to the powers of intuition, creativity, and the irrational, his thought has influenced via Nietzsche, the ideas of vitalism, Dilthey’s life philosophy, Existentism, anthropology, and through Eduard von Hartmann’s philosophy of the unconscious, the psychology of Sigmund Freud. Schopenhauer’s influence on music and literature can be seen in the work of Richard Wagner and Thomas Mann.

Further Reading: See the article on the period after Hegel’s death: 1841.

Schorlemmer, Carl (1834-1892)

German chemist living in England. Friend of Marx and Engels.

Schramm, Karl

German economist. Insurance inspector. Liberal. Took part in the Social-Democratic movement from the 1870s onwards. Expelled from Berlin 1878. Came out in 1884-86 with a criticism of Marxism in which he represented Marx as a degenerate follower of Rodbertus and Lassalle. Later he withdrew from the Social-Democratic movement.

Schreiner, Olive (1855-1920)

Olive Schreiner was born to missionary parents in South Africa. She lived there until family misfortunes led her, at age 13, to seek work as a governess. It was during those eight years, she began her writing career with a semi-autobiographical novel about her life in South Africa. Later she would move to England to attend medical school, and there, would become an activist in socialist circles along with her friends, Eleanor Marx and Edward Carpenter. Her novel was published in 1883 as the Story of an African Farm. The book was acclaimed as an important statement of feminism and was very influential for radical women of the time.

Schreiner followed the success of her first novel with political and social short stories, essays and novels. In 1894 she returned to South Africa, married Samuel Cronwright and gave birth to an infant girl that died within a day. The themes of women’s labor and emancipation, pacifism, racism, imperialism and the tragedy of the loss of a child are major themes in her writing. For a selection of her works, see the Olive Schreiner section.

Schulze-Delitzsch (1808-83)

Politician and economist, organiser of consumers’ co-operatives for handicraft workers, which were to prevent the decay of their class. Marx wrote to Engels on November 4, 1864: "By chance a few numbers of E. Jones’ Notes to the People (1851, 1852) have come into my hands again; these, so far as the main points of the economic articles are concerned, were written under my immediate guidance and partly also with my direct co-operation. Well! What do I find there? That at that date we were conducting against the co-operative movement (in so far as in its present limited form it pretended to rank as something final) the same polemic -- only better -- as Lassalle carried on ten or twelve years later in Germany against Schulze-Delitzsch." "A cloak for reactionary humbug," Marx called unions of the Schulze-Delitzsch type. (Capital, Vol. I, Chap. X, Note on Robert Owen.)

Schwab, Charles M. (1862-1939)

American steel magnate, headed Bethlehem Steel Co. when it became the leading manufacturer of war materials for the Allies in World War I.

Schwab, Michael (1853-?)

One of the Haymarket defendants. Schwab was born in Kitzingen, Germany and became a socialist as a youth, joining the Social Democratic Worker’s Party. He came to the United States in 1897 where he was employed as the chief editorial assistant on the Arbeiter Zeitung, an anarchist German daily. He played a major role in the founding of the anarchist International Working People’s Association (IWPA). He was only placed at the Haymarket meeting briefly, but was connected by association. Schwab was originally sentenced to death but under public pressure the Illinois Governor converted the sentence to life imprisonment the day before the execution. He was pardoned after serving six years.

Further Reading:

Schwab’s speech in court

Subject: May Day.

Schweitzer, Johann Baptiste von (1833-75)

Lassalle’s successor in the leadership of the Allgemeine Deutsche Arbeiterverein (General Association of German Workers). A Frankfort lawyer, originally a National Liberal, became a follower of Lassalle in the early 1860s. In 1865, in Berlin, Schweitzer founded the central organ of the Lassalleans, the Social-Demokrat, for which he received subsidies from Bismarck. Schweitzer tried to turn the political party which has to lead the class movement of the proletariat into a sect, and opposed the unification of the German workers’ movement. He was a representative of Bismarck’s policy, a Royal Prussian Social-Democrat..