Glossary of People

Pi

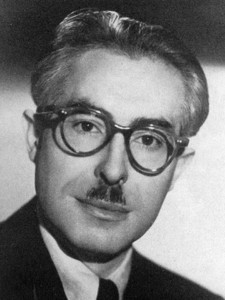

Piaget, Jean (1896-1980)

Swiss psychologist, philosopher and logician, developed theory of intellect formation based on the basis of the extensive study of children. Piaget regards the intellect as a system of operations derived within the subject from external object actions. Piaget’s "genetic epistemology" which showed through a study of child development how concepts and cognitive capacities are developed in a person through human activity in the course of individual growth, grasped the objectivity of concepts established in the mind through subject-object interactivity. Piaget investigated many problems of relating his work in experimental psychology to logic, biology, cybernetics and the broader development of natural science.

Piaget’s early interests were in zoology, and by the age of 15 his publications on molluscs had gained him a European-wide reputation. At the University of Neuchâtel, he studied Zoology and Philosophy, receiving his doctorate in Zoology in 1918. Soon afterward, however, he became interested in psychology, combining his biological training with his interest in epistemology. He first went to Zürich, where he studied under Carl Jung and Eugen Bleuler, and then began two years of study at the Sorbonne in Paris in 1919.

In Paris, Piaget devised and administered reading tests to schoolchildren and became interested in the types of errors they made, leading him to explore the reasoning process in these young children. By 1921 he had begun to publish his findings; the same year brought him back to Switzerland, where he was appointed director of the Rousseau Institute in Geneva. In 1926-29 he was professor of philosophy at the University of Neuchâtel, and in 1929 he joined the University of Geneva as professor of child psychology, remaining there until his death. In 1955 he established the International Centre of Genetic Epistemology at Geneva and became its director. In more than 50 books and monographs, Piaget developed the theme he first discovered in Paris, that the mind of the child evolves through a series of set stages to adulthood.

Piaget saw the child as constantly creating and recreating his own model of reality, achieving mental growth by integrating simpler concepts into higher level concepts at each stage. He argued for a “genetic epistemology,” a timetable established by nature for the development of the child’s ability to think, and he traced four stages in that development.

He described the child during the first two years of life as being in a sensorimotor stage, chiefly concerned with mastering his own innate physical reflexes and extending them into pleasurable or interesting actions. During the same period, the child first becomes aware of himself as a separate physical entity and then realises that the objects around him also have a separate and permanent existence.

In the second, or preoperational, stage, roughly from age two to age six or seven, the child learns to manipulate his environment symbolically through inner representations, or thoughts, about the external world. During this stage, he learns to represent objects by words and to manipulate the words mentally, just as he earlier manipulated the physical objects themselves.

In the third, or concrete operational, stage, from age 7 to age 11 or 12, occurs the beginning of logic in the child’s thought processes and the beginning of the classification of objects by their similarities and differences. During this period, the child also begins to grasp concepts of time and number.

The fourth stage, the period of formal operations, begins at age 12 and extends into adulthood. It is characterised by an orderliness of thinking and a mastery of logical thought, allowing a more flexible kind of mental experimentation. The child learns in this final stage to manipulate abstract ideas, make hypotheses, and see the implications of his own thinking and that of others.

Piaget’s concept of these developmental stages caused a re-evaluation of older ideas of the child, of learning, and of education. If the development of certain thought processes was on a genetically determined timetable, simple reinforcement was not sufficient to teach concepts; the child’s mental development would have to be at the proper stage to assimilate those concepts. Thus, the teacher became not a transmitter of knowledge but a guide to the child’s own discovery of the world.

Piaget reached his conclusions about child development through his observations of and conversations with his own children, as well as others and was involved in numerous dialogues with mathematicians and philosophers of his day, drawing on modern research in mathemtics to inform his ideas about the structural development of the mind and criticising the un-recognised psychological assumptions contained in the work of many philosophers. He only became aware of the work of Lev Vygotsky long after Vygotsky had died, and paid tribute to Vygotsky for having anticipated many of his own most important discoveries.

Further Reading: See text of Genetic Epistemology.

Pichugina, M.

Soviet author and member of the Supreme Soviet of the U.S.S.R. during the 1930s. Pichugina worked on a collective farm until she married and moved to Moscow in 1930. She worked in a factory from a position of unskilled worker to foreman to the deputy to the Moscow Soviet in 1937. In addition to chairwoman duties, she supervised the work of the District Planning Department, the Department of Public Education, and the District Board of Health. She authored, in 1939, Women in the U.S.S.R., a pamphlet that outlines the status of Soviet women in the 1930’s when Stalin was steering policy to "strengthen the family."

Pieper, Wilhelm (1826 - )

German communist living in London after exile from germany. Worked on and off as an assistant for Karl Marx.

Pilling, Geoff (1940 - 1997)

University teacher, Marxist political economist and revolutionary socialist; born Ashton-under-Lyne, March 3, 1940; died, London, August 20, 1997.

In the 1980s, he published two important books; the first on Marx’s Capital, Philosophy and Political Economy, the second an analysis of The Crisis of Keynesnian Economics. But he had already made his mark with an article on the law of value in Ricardo and Marx, in which he launched a salvo against the British Marxist, Ronald Meek.

While still a student at Leeds, he joined the Marxist Society, set up by his future wife, Doria Arram, and met, amongst others, two Yorkshire-based Marxist lecturers, Cliff Slaughter and Tom Kemp, who had left the Communist Party in 1956, after the Twentieth Congress and the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian revolution, and were re-examining their understanding of Marxism.

Soon after, he joined Gerry Healy’s Socialist Labour League, but when, in 1985, Healy was expelled, Pilling supported the orthodox Trotskyist majority against Healy, around Cliff Slaughter.

Pilnyak, Boris (1894-1938)

Soviet author on agrarian issues during the New Economic Policy.

Pilsudski, J. (1867-1935)

Persecuted by the Tsarist government as a youth and exiled to Siberia for the attempted assassination of Alexander III. Became leader of the Polish Socialist Party. In the First World War he commanded a Polish legion in the Austro-Hungarian army. After the war, when the Entente countries set up Poland as an independent state, Pilsudski carried out a coup d’etat and ruled as dictator 1918-1922 and 1926-1935, acting as an supporter of French imperialism.

He personally took charge of Polish actions against the Soviet Union, after invading Ukraine during the Russian Civil War in 1920. He faced the counter-attacking Russian Red Army general Tuchachevsky during the latter’s approach to Warsaw. This counter-attack by the Red Army forced Pilsudski to sign the Riga Treaty of 1921.

Pipes, Richard ( - )

US professor of Harvard University since 1957. Worked for the US National Security Agency in 1981 - 1982 under the Reagan administration, and directed his life towards interpreting the history of Socialism in Russia.

His efforts established the main line of rascist critique against Russian revolutions and governments. In his works he measures all Russians by their level of depravity, examing Russian history from the viewpoint of one failure after another, leading up to the October Revolution, which in his view magnified and proved the backwardness of the Russian people. After the October Revolution, Pipes focuses the point of his chauvinism, comparing the entire Soviet government to a house of prostitutes and bandits, who he explained never had any intention of acting in the interests of anyone but themselves in order to attain the glories of wealth and power.

Pisarev, Dimitri (1840-1868)

Literary critic concerned with family problems and with the ethics of socio-economic reforms.

Pishevari, Seyyed J’afar Jav‚dz‚deh (1892-1947)

The third important Communist leader who played a significant role in the SSRI [Soviet Socialist Republic of Iran] was born to a humble family of Khalkhal, Azerbaijan, in 1892. In 1905 he moved to Baku, where he received his revolutionary education, He joined revolutionaries in the Caucasus and collaborated with the ’Adalat [justice] movement. A well-educated man, he soon became an influential journalist in Baku and published in legal as well as illegal newspapers of the region, such as Achiq Souz, Horriyat, Azerbaijan Foqarasi, Kommunist, Yeni Youl, Yeni Fekr, and many others.

Back in Iran, Pishevari initially worked for the ICP in Gilan and became commissar of the interior in its Communist-led government formed at the end of July 1920. After the demise of the Jangali Movement, he was the lead writer of the Communist newspaper Haqiqat [Truth] published in Teheran. In 1921 he represented the ICP at the third Comintern congress and defended the cause of the party’s radical wing. He worked among Iranian workers until his arrest as one of those responsible for the great oil workers’ strike in Khuzistan in 1929. He was a member of the ICP Central Committee until his arrest in December 1930. Released after the abdication of Reza Shah in 1941, he refused to join the Tudeh party. He founded the newspaper Azhir (Siren) and advocated a radical democratic line.

In 1944 he was elected to the fourteenth Majles, but was rejected by the reactionary-dominated body. Returning to his native province, he established the Democratic party of Azerbaijan, whose main demand was local autonomy from Teheran. After Soviet troops left Iran in 1946 under international pressure, the autonomous government at Tabriz fell instantly. Baqerov, the president of the Azerbaijan SSR, blamed Pishevari for his party’s failure to insist on uniting Iranian Azerbaijan and Soviet Azerbaijan. Pishevari stated that his movement failed precisely because Iranians had the impression that the party wanted the province to secede from Iran and join the ASSR. After a bitter exchange, Pishevari was killed in a mysterious automobile accident, widely interpreted as arranged by Baqerov.

Note: Mir Ja’far Pishevari (Jav‚dz‚deh Khalkhali), Sa’chilmish Asarlari (Baku, 1965); J. Pishevari, T‚rikhcheh-yi Hezb-i ’Adalat (Teheran, 1980); and Y‚d-d‚shth‚-yi Zendan (Tehran, n.d.; prt. Los Angeles, 1988); N. Jah‚nsh‚hlou-Afsh‚r, Sargozasht, M‚ va Big‚neg‚n, vol. 2 (Berlin, 1988). In spite of denials, one of his erstwhile lieutenants in Baku told me [Chaqueri] in September 1992 that Pishevari’s death in spring 1947 was ordered by Soviet leaders.

From: The Soviet Socialist Republic of Iran, 1920-1921: Birth of the Trauma by Cosroe Chaqueri, University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh and London, 1995, p. 470.

Pitt, William ‘The Younger’ (1759-1906)

MP from 1781 and Prime Minister from 1783 at which point he abandoned his support for parliamentary reform and suspended the Habeas Corpus Act. In 1794 he raised the forces among the European powers to fight the armies of the French Revolution. He repressed the Irish Rising of 1798 and forced through the Act of Union of 1801. He introduced various other pieces of repressive legislation notably the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800. He resigned in 1801 but became Prime Minister again in 1804 when again he had to rally the forces of European reaction to fight the French republic.

Pivert, Marceau (1895-1958)

After “patriotic” beginnings, World War I turned Pivert into a pacifist. A union activist and Freemason, he joined the Socialist Party in 1919. Always on the left-wing of the Party, he was a member of the “Bataille Socialiste” (Socialist Battle) tendency, which refused to support a bourgeois government, and in 1935 founded the “Gauche Revolutionnaire” (Revolutionary Left) faction. Aside from his purely political activities he was also behind the production of a number of militant films, and under the Popular Front he had responsibility for the press, radio and cinema.

Expelled from the SFIO he founded the “Parti Socialiste Ouvrier et Paysan” (PSOP), a voice on the independent, anti-authoritarian Marxist left. Though he was the very type of the leftist leader Trotsky sought for the Fourth International, Pivert opposed its foundation as premature. The PSOP collapsed with the war and Pivert went into exile in Mexico, where he worked with Victor Serge and Juan Gorkin in the Front Ouvrier International.

Upon his return to France, he rejoined the SFIO, where after a period on its right he evolved to the left of the party, opposing European defense pacts and the war in Algeria.