Bl

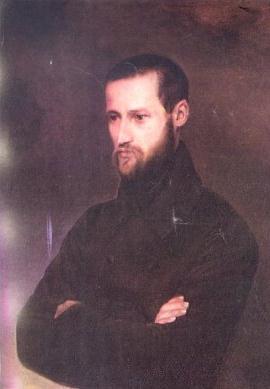

Blanc, Louis (1811-1882)

French politician and historian. A socialist that favored reforms, he called for the creation of procedure cooperatives in order to guarantee employment for the city poor.

Early years

He was born in Madrid, his father held the post of inspector-general of finance under Joseph Bonaparte. Failing to receive aid from Pozzo di Borgo, his mother's uncle, Louis Blanc studied law in Paris, living in povertyagi, and became a contributor to various journals. In the Revue du progres, which he founded, he published in 1839 his study on L'Organisation du travail. The principles laid down in this famous essay form the key to Louis Blanc's whole political career. He attributes all the evils that afflict society to the pressure of competition, whereby the weaker are driven to the wall. He demanded the equalization of wages, and the merging of personal interests in the common good-- "à chacun selon ses besoins, de chacun selon ses facultés," which is often translated as "from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs." This was to be affected by the establishment of "social workshops," a sort of combined co-operative society and trade-union, where the workmen in each trade were to unite their efforts for their common benefit. In 1841 he published his Histoire de dix ans 1830-1840, an attack upon the monarchy of July. It ran through four editions in four years.

The Revolution of 1848

In 1847 he published the two first volumes of his Histoire de la Revolution Française. Its publication was interrupted by the Revolution of 1848, when Louis Blanc became a member of the provisional government. It was on his motion that, on 25 February, the government undertook "to guarantee the existence of the workmen by work"; and though his demand for the establishment of a ministry of labour was refused—as beyond the competence of a provisional government—he was appointed to preside over the government labour commission (Commission du Gouvernement pour les travailleurs) established at the Palace Luxembourg to inquire into and report on the labour question.

The revolution of 1848 was the real chance for Louis Blanc’s ideas to be implemented. His theory of using the established government to enact change was different from those of other socialist theorists of his time. Blanc believed that workers could control their own livelihoods, but knew that unless they were given help to get started the cooperative workshops would never work. To assist this process along Blanc lobbied for national funding of these workshops until the workers could assume control. To fund this ambitious project, Blanc saw a ready revenue source in the rail system. Under government control the railway system would provide the bulk of the funding needed for this and other projects Blanc saw in the future.

When the workshop program was ratified in the national assembly, Blanc’s chief rival Emile Thomas was put in control of the project. The national assembly was not ready for this type of social program and treated the workshops as a method of buying time until the assembly could gather enough support to stabilize themselves against another worker rebellion. Emile Thomas’s deliberate failure in organizing the workshops into a success only seemed to anger the public more. The people had been promised a job and a working environment in which the workers were in charge, from these government funded programs. What they had received was hand outs and government funded work parties to dig ditches and hard manual labor for meager wages or paid to remain idle. When the workshops were closed the workers rebelled again but were put down by force by the national guard. The national assembly was also able to blame Blanc for the failure of the workshops. His ideas were questioned and he lost much of the respect which had given him influence with the public.

Between the "sans-culottes", who tried to force him to place himself at their head, and the national guards, who mistreated him, he was nearly killed. Rescued with difficulty, he escaped with a false passport to Belgium, and then to London. In his absence he was condemned by a special tribunal at Bourges, in contumaciam, to deportation. Against trial and sentence he alike protested, developing his protest in a series of articles in the Nouveau Monde, a review published in Paris under his direction. These he afterwards collected and published as Pages de l'histoire de la révolution de 1848 (Brussels, 1850).

Exile

During his stay in Britain he made use of the unique collection of materials for the revolutionary period preserved at the British Museum to complete his Histoire de la Revolution Française 12 vols. (1847-1862). In 1858 he published a reply to Lord Normanby's A Year of Revolution in Paris (1858), which he developed later into his Histoire de la révolution de 1848 (2 vols., 1870-1880). He was also active in the irregular masonic organisation, the Conseil Supreme de l’Ordre Maconnique de Memphis. His membership in the London-based La Grand Loge des Philadelphes is unconfirmed.

Return to France

As far back as 1839 Louis Blanc had vehemently opposed the idea of a Napoleonic restoration, predicting that it would be "despotism without glory," "the Empire without the Emperor." He therefore remained in exile until the fall of the Second Empire in September 1870, after which he returned to Paris and served as a private in the national guard. On 8 February 1871 he was elected a member of the National Assembly, in which he maintained that the republic was "the necessary form of national sovereignty," and voted for the continuation of the war; yet, though a leftist, he did not sympathize with the Paris Commune, and exerted his influence in vain on the side of moderation. In 1878 he advocated the abolition of the presidency and the Senate. In January 1879 he introduced into the chamber a proposal for the amnesty of the Communards, which was carried. This was his last important act. His declining years were darkened by ill-health and by the death, in 1876, of his wife Christina Groh, whom he had married in 1865. He died at Cannes, and on 12 December received a state funeral in the Père Lachaise.

His political legacy

Louis Blanc possessed a picturesque and vivid style, and considerable power of research; but the fervour with which he expressed his convictions, while placing him in the first rank of orators, tended to turn his historical writings into political pamphlets. His political and social ideas have had a great influence on the development of socialism in France. His Discours politiques (1847-1881) was published in 1882. his most important works, besides those already mentioned, are Lettres sur l'Angleterre (1866-1867), Dix années de l'Histoire de l'Angleterre (1879-1881), and Questions d'aujourd'hui et de demain (1873-1884).

V.I. Lenin, L. Trotsky and other revolutionary Marxists often used his name as an epithet to denote the opportunist and conciliatory tactics of the Mensheviks and others opposed to the cause of the revolution and the interests of the working class.

Selected works

1. Louis Blanc (1841). The History of Ten Years, 1830-1840 (Vol. 1). New York: Chapman and Hall. pp. 628. ASIN B0006BWS4Y. http://books.google.com/books?id=hH52mPMmlzcC&vid=OCLC19653369&dq=Grochow+1831&ie=UTF-8&jtp=1.

Bland, William “Bill” (1916-2001)

Bill Bland was born in the North of England, into a middle class home. He spent his politically formative years in the army of New Zealand, where he was active in the Communist Party as an educator. He returned to Britain in the post-war years as an ophthalmic optician. In the 1950’s Bland witnessed the Communist Party of Great Britain embracing the “Peaceful Road to Socialism", and Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin. Bland believed these “revisionist” stances were incorrect and anti-Marxist-Leninist.

Bland therefore became a member of several anti-revisionist formations in Britain. He soon joined forces with Mike Baker in the Marxist-Leninist Organisation of Britain (MLOB). Shortly thereafter, the ‘Cultural Revolution’ occured in China, and prompted by a barrage of questions, Bland undertook a systematic study of Mao. He found that he could not agree with Mao’s theory of the ‘New Democratic State’; and penned within months, the first refutation of Mao from the point of view of a pro-Stalin supporter. At that time, the MLOB rapidly dwindled in size as many members retained affection of Mao. This was to be the first of Bland’s many un-popular analyses in the pro-Stalin wing of the Communist movement.

Bland spent the rest of his life trying to answer the question: “How had revisionism become ascendant?”

Bland came to the conclusion that Stalin had been in a minority position in the Politburo, surrounded by hidden revisionists too clever to openly attack Marxism-Leninism; further, they had straight-jacketed Stalin by means of erecting the “Cult of Personality,” which was then used as a weapon against him. Bland felt that Yezhov had subverted the secret services, who had been replaced at Stalin’s behest by Beria. Bland pointed for example, to the release of many thousands of wrongly imprisoned Bolsheviks. Bland then argued that by the 18th Party Congress Stalin had been excluded from the highest echelons of the party decision making apparatus, and had counter-attacked with his pamphlet “Economic Problems of the USSR.”

Stalin’s essay was a seminal attack on Nikolai Vosnosensky, who was linked to Khrushchev. Cosequently argued Bland, the later economic changes re-establishing capitalism in the USSR had been fought to a standstill by Stalin. Bland therefore argued a special significance for Stalin’s last work. As Bland saw it, once Stalin was dead, the capitalist “reforms” of Vosnosensky were enacted by Khrushchev and his successors. He formulated these views in articles that culminated in the book ‘Restoration of Capitalism in the USSR’, published in 1981.

Follwing his analysis of Maoism as ‘left revisionism’, Bland began to question his own long-standing support for the then pro-Chinese Party of Labour of Albania, but concluded that the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania remained socialist. Before the 20th party Congress of the CPSU, Bland had founded the Albanian Society of Britain, at the invitation of the PSRA. Despite now being officially ostracized by Albania, Bland continued his work running the Albanian Society, and organizing an enormous education on this isolated solitary socialist country. In those years, he became an acknowledged authority on all things Albanian. He published an English-Albanian dictionary and he fielded any manner of queries upon arcane features of Albanian life, history, music, foods, geography, customs and mores etc.

While China was supported by the Albanian party, some of the Maoist parties had run an explicit party front Albania Society, resisting Bland’s call for one single, united front Albania Society, regardless of ‘narrow’ party affiliation. Following Hoxha’s open attack on Mao, some of these Societies split and some died. Their remaining members were correctly advised by the foreign Liaison committee of the PSRA, to join with Bland’s organisation to form one United Front of support for the PSRA. But they launched attempts to remove Bland’s leadership, charging that an emphasis on all aspects of life – such as music etc – was “anti-Marxist-Leninist,” and “insufficiently political,” and that Bland should be removed. The membership rejected this attempt to remove Bland. The Society continued till the revisionist take-over of the PSRA by Ramiz Alia, at which point Bland resigned from the Albania Society.

It was primarily differences over Bland’s analysis of Albania as Socialist that precipitated the split in the MLOB in 1975, following which, the Communist League came into existence. The Communist League from its inception always supported the Peoples Socialist Republic of Albania as a solitary socialist state. Those that stayed with the MLOB, including Mike Baker and his supporters, rejected that position.

One specific aspect of modern revisionism, to which Bland paid close attention, was the subversion of the second stage of socialist revolution, into a static national democratic deviations. For Bland, this represented a distortion from the Marxist-Leninist theory of the nation. Into these categories, Bland placed the pseudo-‘socialist’ revolutions of China, Cuba, North Korea, Vietnam and Tanzania. He argued that all of these had ignored Lenin’s injunction not to build a ‘Chinese Wall’ between the first (national democratic) stage of revolution and the second (socialist) stage. Bland also argued that other, phenomena such as the “Black Nation” in the USA, “Black Racism” and “Scottish, Welsh and Cornish Nationalism", in Britain, represented national deviations away from socialist revolution.

These views led him to challenge fundamental Stalinist premises: If the Soviet Union had been permeated by a class war involving the highest echelons of the Party, was the Comintern any different?

Bland puzzled over several related matters: Why had the Comintern performed so many about-turns on key questions such as the nature of the United Front? Was Stalin really ‘in control’ of the Comintern? Why had the Peoples Front governments been supported beyond any credible point by European communist parties, especially in France, in assisting a fascist take-over? And why did the ultra-left rejections of a united front of the late 1920’s swing suddenly into ultra-right distortions of a correct United Front policy? Etc.

Bland argued that the first ultra-left deviations in the Comintern, in the period from about 1924 to 1928 had allowed fascism to take power in Germany. In the same period, under the cover of this ultra-leftism, Manuilsky and Kussinen had destroyed the Indian revolution by sabotaging Stalin’s line of the Workers and Peasants parties. Bland thought that the second right deviations, from about 1930 onwards had prevented the masses of Europe taking power under Communist Party direction.

Bland now further argued that Stalin had not been in a leadership position in the Comintern since around 1924; as follows: Initially Zinoviev had exercised the leadership, and thereafter Bukharin. When both were exposed as "revisionists" they were purged from further influencing the Comintern. Both were later shot. Thereafter Dimitrov, Otto Kuusinen, and Dimitri Manuilskii exercised the Comintern leadership. Bland argued they had perverted a correct implementation of Marxism-Leninism. Dimitrov had been sprung from the German Fascist prisons thanks to a rather dubious, and surprising “leniency” of the German fascists. “Why?”, asked Bland, replying that a pact had been struck; as shown when Dimitrov went on to subvert United Front tactics into the right deviation of supporting “Popular Front” governments beyond Marxist-Leninist principles of the correct United Front tactics.

It was for these reasons, argued Bland, that the Comintern was dissolved by Stalin. Stalin then created the Cominform under a completely different leadership, led by his most trusted lieutenants such as Zhdanov. It must be remembered, said Bland, that it was the Cominform that had exposed the Western Communist parties plans for implementing right deviationist policies, and the Titoites for allying with the USA. During this latter historic confrontation Stalin overtly supported Albania and Hoxha against Tito.

Apart from his theoretical works, Bland wrote a number of plays, directed two films, and created a ballet. A life-long intense love of the arts – especially cinema and the theatre – led him to re-affirm the principles of Socialist Realist Art. He wrote widely on theatre and film, and on the history of theatre.

In Britain he led the Communist League to urge the principled unity of all Marxist-Leninist forces, hence Bland’s role in the early stages of the National Committee for A Marxist-Leninist Unity (NCMLU). Bland also formed the Stalin Soicety in the UK. But the pro-China factions within the Stalin Society that ensured Bland’s later expulsion. He was a key figure in the formation of the International Struggle Marxist-Leninist, and was cited as a major influence by Alliance Marxist-Leninist (North America).

Further Reading: Bill Bland Reference Archive.

by Hari Kumar

Blanqui, Louis-Auguste (1805-1881)

Born February 1, 1805; died January 1, 1881: Revolutionary socialist, spent 33 of his 76 years in prison as a result of fighting for the working class. Blanqui neither cared for economic nor social/historical theory, but dedicated his heart and mind to the theory and practice of workers' revolution. Blanqui recognized, as a result of extreme police persecution, that a successful workers revolution in 19th-century France could only be led by a small group of disciplined workers.

At 13 years old, Blanqui had moved to Paris to live with his older brother, Adolphe. In Paris Blanqui studied law and medicine until 1824; completing his education when he was 19 years old. Beginning in 1827, he took an active part in students demonstrations against the restored Bourbon monarchy, which he followed through to the Revolution of July 1830 (which had established to the monarchy of Louis-Philippe). Outraged by all the blood workers had spilled in the preceding years to see it commadered by an autocrat convinced Blanqui of the need for a workers revolution.

A member of the Society of Friends of the People (Société des Amis du Peuple), Blanqui was first imprisoned in 1831, and again in 1836 as a result of his association with this illegal society. As these acts of extreme police persecution, workers movements could only exist as small, disciplined and secretive societies. Having clear vision, Blanqui (much like Lenin) concluded that only extremely disciplined workers could achieve workers revolution in those conditions.

Blanqui organized the Society of the Seasons (Société des Saisons) and attempted an armed instruction on May 12, 1839 against the Hôtel de Ville (the City Hall) of Paris. Isolated both physically and politically from Paris workers, the 500 armed revolutionaries were slaughtered in less than two days of fighting. Blanqui, who managed to escape the disaster, was caught and sentenced to death. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment on the island of Mont-Saint-Michel.

His stay in the deplorable prison crushed him physically, and after four wrenching years of solitary confinement, he was granted clemency to be released to a prison hospital at Tours, from where he was released after five years of recovery, shortly before the Revolution of 1848.

Returning to Paris, he created a new reformist society – the Central Republican Society (Société Républicaine Centrale), through which he attempted to reform the new provisional government to adopt policies in favor of the working class. The conservative government that was elected to the Constituent Assembly, had different plans however, and found in Blanqui a scapegoat for radical workers' demonstrations. He was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment on the false charge of having participated in a demonstration which he in fact had disapproved of.

Released in 1859, he returned to organizing workers' parties and was arrested again in 1861, and held until he escaped to Belgium in 1865. His all-too frequent stays in prison earned him the name l'enfermé (the locked-up one). Blanqui did not return to Paris until the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 began.

After Napoleon III capitulated at the Battle of Sedan, and the siege of Paris began, Blanqui agitated against Prussian occupation of France, suggesting how Paris should best defend itself. On October 31, 1870, Blanqui lead revolutionaries to attempt to overthrow the government, and succeeded in capturing the Hôtel de Ville and set up a government with Blanqui at its head. Just a day later, however, the government stormed the Hotel and arrested Blanqui and many of other revolutionary leaders for treason. His remaining Paris followers again attempted to overthrow the government, on January 22, 1871, this time unarmed. Soldiers guarding the Hôtel de Ville open fire on the protesting workers, killing hundreds.

After the beginning of the French Civil War of 1871 , the Paris Commune was elected, and Blanqui was elected president. The government of Thiers refused to release Blanqui, despite the legitimate election of him to public office. After tens of thousands of workers were massacred in Paris by government troops as a result of their struggle to establish the first workers government ever created, Blanqui was kept locked up in prison. In April 1879, he was elected deputy for Bordeaux; however the government refused to recognize the election. With great workers unrest, however, they weighed their options and decided that releasing the 74-year-old man would put out many more fires than it would start. Blanqui continued to agitate for Socialism, and died at nearly 76 years old from apoplexy.

See Louis Auguste Blanqui Archive.

Blenkle, Konrad (1901–43) .

Bakery worker, from working-class family; joined Youth in 1919 and KPD(S) in 1920; worked for Soviet embassy in Berlin; became secretary of Communist Youth in 1923, supported KPD (Kommunistischen Partei Deutschlands/German Communist Party) Left. Chairman of Communist Youth and member of Central Committee in 1924; deputy in 1928; in disgrace thereafter. Worked illegally in 1933–4. Emigrated and led some illegal work in Germany, from Copenhagen. Arrested, sentenced to death, executed in Plötzensee.

Bloch, Ernst (1885–1977)

German Marxist philosopher. He taught at the University of Leipzig (1918–33), drifting toward Marxism during the 1920s. He fled the Nazis after 1933, moving first to Switzerland and then to the United States. Bloch's first major work, The Principle of Hope, which was published in German, emphasized the role of hope as a human drive. He returned to Leipzig in 1948, where he remained until conflict with Communist Party officials compelled him to defect to West Germany (1961). There, he taught at the University of Tübingen.

See Ernst Bloch Archive.

Bloor, Ella Reeve "Mother" (1862 - 1951)

American labor organizer and long-time activist in the socialist and communist movements.

Early years

Ella Reeve "Mother" Bloor was born Ella Reeve on Staten Island, on July 8, 1862, and grew up in Bridgeton, New Jersey. She was married first to Lucien Ware, then Louis Cohen, and finally Andrew Omholt. After marrying Lucian Ware when she was nineteen, she was a mother of four by 1892. Her daughter, Helen Ware, was a concert violinist while son, Harold Ware, became an agriculture expert as an activist in the Communist Party of America. One of her other sons was Buzz Ware, an artist and prominent leader in the Village of Arden, Delaware, where she lived for many years.

Political career

Ella became involved in several reform movements including the prohibitionist Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and women’s suffrage. She was the author of two books for children, Three Little Lovers of Nature (1895) and Talks About Authors and Their Work (1899). Gene Debs, railroad union organizer and key figure in the Social Democracy of America.

In 1897 Ella was a founding member of the Social Democracy of America, a new organization established by her friend Eugene V. Debs and Victor Berger — a group which would later emerge as the Social Democratic Party (SDP). She later recalled:

"When I joined the Social Democracy I was living in Brooklyn and I had married for the second time. My husband, Louis Cohen, was a socialist. I was pregnant with the first of the two children of that marriage. The railroad men [Debs supporters] came to my house so I could continue to act as [local] secretary.

"But a new disappointment was in store for me. The Social Democracy, I soon discovered, was a utopian scheme. Debs’ plan was to form an ideal colony out West to show by example that socialism could work. From the outset I told the members of my group that this colonization scheme was unsound, not real socialism at all. I stayed with it for a while because of my loyalty to Debs, and because this was the nearest thing I had yet found to a socialist movement.

"Debs set up a paper in Chicago called The Social Democrat. At his request I wrote a children’s column for it. The children answered the appeals of Debs and his colonization committee by sending me money. I felt it was unfair to collect money for something that did not yet exist. People were already selling out businesses to join the colony. A national convention was held in Chicago [June 7-11, 189 and our local sent delegates. Among them was my husband who still felt that anything Debs was in must be all right. I agreed to withhold final judgment until the delegates returned. When they came back and reported that plans to establish the colony would continue, I resigned. I simply could not stay with anything so unscientific.

Shortly after her resignation from the Social Democracy, Ella attended a meeting in New York of the Socialist Labor Party, at which editor of the party newspaper Daniel DeLeon was the speaker:

"He was small and slight and prematurely gray, and spoke very deliberately and convincingly.

"The Socialist Labor Party was a revolutionary party in those days and DeLeon, its leader, was a brilliant theoretician and speaker, a courageous fighter against capitalism.... I was impressed with his analysis of the evils of the capitalist system, and of the fallacy of isolated socialist colonies as a way of achieving socialism. I felt that at last here was scientific socialism and joined the SLP.

"Daniel DeLeon and I became friends.... I became very much interested in the New York Labor News Company — the first organization that published revolutionary books and pamphlets in English on a large scale. Its manager was Julien Pierce. Together we proofread the pamphlets translated by DeLeon, often having o reconstruct the English, a greater task than we ever let him know."

Ella was elected to the governing General Executive Board of the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance (ST&LA), the SLP’s trade union affiliate. She was also the ST&LA’s organizer for Essex County, New Jersey and was sent to Philadelphia by the organization in an effort to organize street car workers there.

Ella recounted her growing disaffection with the SLP in her 1940 memoir:

"Gradually the defects of the SLP were brought home to me. I found many workers antagonistic because I was organizing a rival union. The STLA was weakening the AF of L by drawing off its more radical elements and leaving the reactionaries in control, and was itself organized on too narrow and sectarian a basis to accomplish anything. Furthermore, the SLP as a political party had little real influence because DeLeon was against taking part in the immediate struggles of the workers.... I began very early to see the importance of a united trade union movement, and felt that Socialists should work within the AF of L. I felt that DeLeon understood Marx very well abstractly but knew little about the practical needs of the labor movement.

"The last time I talked with DeLeon I told him I was moving to Philadelphia and was willing to accept the secretaryship of the SLP local there, which had been offered me, but I could not go along with their principles wholeheartedly. As a good friend of mine, DeLeon accepted what I said without anger, but would not change his methods."

Soon after her arrival in Philadelphia, a state convention of the SLP decided to leave the party en masse to form a new organization in the nether region between Morris Hillquit’s dissident so-called "Kangaroo" faction which broke away in 1899 and DeLeon’s hardline SLP. Ella opposed this new organization, which called itself "The Logical Center" and included Lucien Sanial, a former top official in the SLP. Ella had been watching with interest the formation of the Socialist Party of America (SPA) in 1901 and decided to leave her new Pennsylvania comrades to rejoin her friend Gene Debs as a member of his new organization.

In subsequent years, Ella worked as a trade union organizer and helped during industrial disputes in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Colorado, Ohio and New York. In 1905 she helped a fellow member of the Socialist Party of America, the author, Upton Sinclair, to gather information on the Chicago stock yards. This material eventually appeared in Sinclair’s best-selling book, The Jungle. Rumour has it that Sinclair sent her along with a Mr. Bloor as a faux couple to be able to innocently gather data on the meat yards of Chicago. Although they were not married, Ella adopted the name Mother Bloor.

A leading figure in the Socialist Party of America, she ran several times unsuccessfully for political office, including secretary of state for Connecticut, Governor of Pennsylvania, and Lieutenant Governor of New York in 1918.

Ella Reeve Bloor was an adherent of the Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party of America exited that organization form the Communist Labor Party. In 1921 and 1922 attended the second conventions of the Comintern in Moscow. She was also a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party USA from 1932 to 1948.

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Bloor became an advocate of American participation in World War II. Later she argued for an early invasion of Europe to create a Second Front.

Death and legacy

Ella Reeve Bloor died on August 10, 1951 in Richlandtown, Pennsylvania. She is buried in Harleigh Cemetery in Camden, New Jersey.1

Bloor’s autobiography, We Are Many, was published in 1940 and served as the basis for the Woody Guthrie song, "1913 Massacre."

Leon Blum (1872-1950)

French socialist leader, head of state of the Popular Front government. Politicized by the Dreyfus Affair, in which he was an active participant, Blum became a socialist in 1898. Politics became the principal focus of his life after World War I, when he was the leader of the faction of the Socialist Party that refused to join the Third International at the Tours Congress of 1920. A key socialist parliament member Blum headed the Popular Front government in 1936, which implemented measures like the 40 hour week and paid vacations. Arrested by the Vichy authorities after the fall of the Third Republic, his trial was suspended when Blum succeeded in putting the Vichy state on trial. He was subsequently arrested by the Germans and intended in a special house inside the Buchenwald concentration camp. Released in 1945, he returned to France and French politics as leader of the Socialist Party.

See Leon Blum Archive.

Blyumkin (or Blurakin ?–1929)

Killed the German ambassador Mirbach, in 1918 Russia, in order to provoke war between Soviet Russia and Germany, was pardoned after Germany’s defeat had made it safe to do this. He resumed his work in the Cheka (later the GPU). In 1929 he visited Trotsky in exile, taking back with him a letter to Russian oppositionists. He was betrayed (apparently, by Radek) and executed. Blyumkin was a Left SR who helped coordinate terrorist actions against the Bolsheviks. His assassination of Mirbach was an attempt, as stated, to provoke Germany into attacking the Soviet Republic and workers’ state. The assassination of Mirbach was perpetuated by the same political fringe that attempted the assassination of Lenin. It was not done at the behest of the Bolsheviks, but rather it was directed against them.