IF we were concerned only with the strike as an incident wherein the miners were in trouble and other trade unions came to their assistance, it would be an easy matter to give the facts and figures relative to the mining industry, the breakdown of negotiations, etc., and our leading question would be answered. But sufficient evidence has already been given to reveal it as a most important landmark in British history, and much more than such simple data is necessary if we are to place this great event in its proper historical perspectives.

Of course it will be necessary to give the facts re the coal industry, and these we shall give, because the coal industry holds a key position in British economic life and has been for almost a decade the storm-centre of the economic difficulties of Britain. These facts however do not stand alone. Much more than generosity on the part of other trade unions is required to produce such united action on the part of the workers as was manifest in this strike.

Social forces do not arrive at such sharp alignments and marshal themselves in “battle formation” without some common factors being at work in all industries and in all classes. The strike situation can only be regarded as an indication of a general crisis. I therefore propose to place the facts of the coal crisis in relation to the outstanding features of the crisis in general.

For our purpose there is no need to go farther back than the year 1919. This was a critical year for British capitalism. It had to face the sequel to its victory in the imperialist war of 1914-18. It had to re-adjust its economic and social life under exceedingly difficult circumstances. Even during the war large bodies of workers were breaking away from the social patriotism which had tied the unions to the State machine and brought the Labour Party into coalition with the Liberals and Tories. The end of the war saw the termination of Labour’s coalition policy and the whole Labour apparatus subject to a flood of working class demands.

In rapid succession, early in 1919, the miners, engineers, railwaymen, dockers, etc., launched their programmes for higher wages and shorter hours. The miners had put forward additional demands of a character that was to place them at the front of the struggle for some time to come. Besides the wages and hours questions, they were demanding nationalisation of the mines and democratic control of the industry. They threatened strike action. Strikes and threats of strikes characterised the whole situation. The Government called a national Industrial Conference to include all the trade unions and representative employers, to work for industrial peace, but miners, railwaymen, transport workers and engineers refused to attend—a refusal which was symptomatic of the feeling of strength possessed by the workers and their leaders. The magnitude of the awakening of interest in the workers’ movement is seen at a glance in the figures of trade union membership during these two years, 1919 and 1920. In 1913 the trade unions mustered a total strength of 4,189,000. In 1919 it was 8,081,000 and in 1920 it rose to 8,493,000.

It would be possible to show a long list of capitalist concessions here: how even real wages advanced in front of the pre-war level and how the aggregate reduction of hours of labour for six and a half million workers amounted to 41,755,000 per week, and to add many other gains. Put our purpose here is to show the process of class consolidation and development that has gone on as a necessary preliminary to such events as the General Strike of May, 1926.

This found expression in the ranks of the ruling class in a growth of discontent against the Liberal elements of the Coalition, a demand for economy, and an increasing alarm at the prospect of the termination of the artificial period of prosperity. In the ranks of the workers it took shape in the fusion of the Socialist Parties, the B.S.P. (British Socialist Party), the Socialist Labour Party and several other socialist groups with the Shop Stewards and Workers’ Committees into a Communist Party directly affiliated to the Communist International. This was a most important step forward, representing not only the beginnings of a class party within the ranks of the working class movement but the tightening of the bonds between the British working class and the revolutionary workers’ movement in Europe.

During the same period, arising out of the struggles of the unions, especially the railway strike, began a centralising process in the unions culminating in the formation of the General Council of the Trades Union Congress in place of the Parliamentary Committee of the Congress, which had functioned only as a kind of clearance committee of the unions to pass on the resolutions to the Parliamentary Labour Party.

The T.U.C. went further and established a joint committee of the General Council and the Labour Party Executive, and even attempted to get the Co-operative Union to take part. It was not until September, 1921, that the first General Council was elected, but it was a direct product of the struggle of 1919 and 1920. This was strengthened by the great movement of 1920 which threatened a General Strike, where through the joint conference of the Trades Union Congress and the Labour Party a national Council of Action was formed with the counterpart in every district. The Councils of Action passed away with the passing of the crisis but the influence created thereby strengthened the line of centralisation indicated. By the end of 1920 therefore we are witness to a widespread awakening of the workers on a scale hitherto without parallel, a general move towards centralisation in the unions and a crystallisation of its growing class consciousness in the formation of the Communist Party.

With the end of 1920 came also the end of the period of concessions and of the widespread advance of the workers. The successes that had been achieved by unions acting almost as independent bodies prevented a rapid strengthening of the centralising tendencies I have mentioned. The General Council was not in being, and the working class movement was totally unprepared for the rough period that was immediately before it. The ruling class was on the contrary well centralised in the government of the day. Having safeguarded itself thoroughly from political encroachments, and dodged the issue of nationalisation raised by the miners, it proceeded with the policy of decontrol, i.e., the relaxation of State control of private industry, and an ending of the process of currency inflation, which was reaching dangerous proportions.

Alarm was spreading through the ranks of the capitalist class. The demand increased for a cessation of the policy of concessions, for drastic retrenchment, and for something to be done to “get back to 1914.” A terrific slump began in 1921 which has remained through succeeding years and is the basis upon which the process of class consolidation has been increasingly accentuated. The severity of the situation is seen at once in the financial and economic figures of these years.

The total of State expenditure as revealed in the national Budget amounted in 1913 to £172,000,000. In 1920-21 it had risen to £1,145,000,000, and in spite of all the efforts at retrenchment remains in 1925-26 at £824,000,000. Besides this, colossal increase, municipal expenditure had risen from £71,276,000 raised in rates before the war to £105,590,000 in 1920, £151,865,000 in 1921 and remains about the figure of £160,000,000 to-day. These figures mean a change of from 18 per cent. to 40 per cent. of national income passing into the hands of the State and Municipal authorities.

This great increase of taxation aggravated the difficulties of industry. How severe these difficulties were will be realised from the fact that with all the attempts at artificial restoration, all the counter attacks upon the workers, the export figures have not reached more than 75 per cent. to 85 per cent. of 1913. This position is made worse by the fact that there had been a large increase in technical machinery and heavy expenditure following on the “readjustments necessary for peace industry.” The choice before the capitalist class was, therefore, either further inroads into their wealth or a counter offensive against the working class. They choose the latter and class warfare began in real earnest with the odds on the capitalists. The working class movement, and especially its leaders, was saturated with social pacifism, the apparatus at its disposal was divided against itself, and the Communist Party too young and small to have direct influence on the course of events. The nearest approach to a machine capable of putting up a general resistance was the Triple Alliance of Miners, Railwaymen and Transport Workers.

The miners were the first in the line before this counter offensive. The Triple Alliance collapsed at the thought of the implications of common action, or shall I say its leadership collapsed and prevented it functioning? After the collapse of the Triple Alliance it was an easy matter to deal with the rest. But not without resistance on the part of the workers. In 1921 86,000,000 working days were lost in dispute. In 1922 there were 20,000,000 days lost, and in 1923 there were 10,000,000 lost in the same way. It is estimated that in two years the workers lost £10,000,000 per week in wages.

The wage attack slowed down a little in 1923. Will anyone suggest that these terrific years of debacle had nothing to do with the preparation of the forces for the General Strike of 1926? We shall see.

Simultaneous with the attack came the breakdown) in industry and the growth of a vast army, of unemployed. In 1921, for example, the Government statistics show 1,509,029 unemployed and in 1922 there were 1,828,000. The irritation and anxiety in the ranks of the capitalists knew no bounds. Discontent among so class conscious a social force naturally drove their sympathies in the direction of their most violent defenders, and from this onward the process of class assimilation and consolidation goes on rapidly within their ranks. It appears to be the fate of classes that come to power to hold on to the last ditch long after the justification for their existence as a ruling class has passed away. The British ruling class appears to be no exception to this rule, for the whole record of these years is a study in the contrast between its inability to solve its economic and social problems and the intensification of the grip of political power. This we will show in order to substantiate our case in relation to the General Strike and its place in British history.

The registered number of unemployed (which by the way should be regarded as a minimum figure because of the various changes have been made in the manner of recording the unemployed in order to hide the real situation) are as follows:—

1921 . . . . . 1,509,029

1922 . . . . . 1,828,223

1923 . . . . . 1,343,725

1924 . . . . . 1,134,742

1925 . . . . . 1,237,700

Let us examine the figures of a number of leading industries. The decline of agriculture in Britain had become notorious before the war. During the war by extraordinary methods the decline was stopped and an improvement shown. But the story afterwards is the continuation of the pre-war story.

In 1913 there were 11,335,000 acres arable land and 16,071,000 acres under permanent grass. In 1919 there were 12,309,000 acres arable land and 14,4329,000 grass. In 1924 there were 10,929,000 acres arable and 14,948,000 acres grass land. That is one million and a half acres less land under cultivation in 1924 than in 1913. During 1925 the decline has continued by a further fall of 300,000 acres.

The iron and steel industry offers little consolation. The monthly average for 1913 shows 338 blast furnaces working and producing 855,000 tons of pig iron and 638,000 tons steel ingots. In 1920 the corresponding figures are 284 furnaces working, producing 699,000 tons pig and 755,600 tons steel. In 1924 there were 181 furnaces working with an output of 601,900 tons pig iron and 685,000 tons steel. In 1925 the position is worse still, with only 164 furnaces working in the month of March out of 482 in existence.

The exports of machinery in 1913 amounted to 689,389 tons. In 1922 they fell to 400,000 tons and have not yet appreciably improved on that figure. The story of shipbuilding is blacker still The quarterly rate of ships tonnage laid down according to Lloyd’s register was in 1919, 601,000 tons; in 1920, 599,000 tons; in 1921, 142,000 tons; in 1923 it was 101,000 tons and 1924, 263,000 tons.

The cotton exports of the years 1922 onwards are only as yet 60 per cent. of the amount of 1913, while the coal industry shows a heavy decline in all directions with the exception of domestic consumption; decline in export in 1924 is to the extent of 12,000,000 tons as compared with 1913. A still more alarming feature is the growing gap between imports and exports—imports steadily increasing and exports steadily declining. For example, in 1924 imports had risen to 4.1 per cent. above 1913 imports and the exports had fallen 24.5 per cent. below 1913 (measured in 1913 prices).

Sufficient data has now been given to the serious factors weighing upon the British capitalist class, data which reveal the foundation of the class movement we are emphasising. In giving these data I am not concerned with proving, whether the capitalist class will recover its position, or will not recover, but in showing that that they have not recovered and that this failure to recover in the period under survey lies at the bottom of the political development which leads to the General Strike of May 1926.

Already we have recalled the breakaway of the Labour forty from the Coalition Government of the war period. The popular discontent and the anxiety of the ruling class, roused by the widespread movement of the workers and their own failure to solve their economic difficulties, shattered the coalition of the Liberals and Tories in 1922 and led to the ascendancy of the Conservative Party. This was the beginning of the end of the Liberal Party and the concentration of the ruling class in its most reactionary forms. Within a year it passed swiftly away from Liberalism changed its leaders and plunged for a tariff war as a means of salvation for its broken down industry. How far this was the principal reason for its actions, or how far it was a conscious manœuvre for the purpose of outwitting the Labour Party is uncertain, but the fact remains that the Conservative Party under Mr. Baldwin’s leadership threw away a large majority. It launched into a general election knowing full well the growth of Labour support, and paved the way to a Labour Minority Government. During the interval of nine months it vigorously overhauled its Party, re-adjusted its leading team, secured the commitment of every leader of the Labour Party to the fundamental lines of its own policy, and then shattered the Labour Government.

It raked the banner of class warfare high, denounced the Liberals as incapable of facing the dangerous Labour movement, unhesitatingly used forgery as a means to colour the Labour movement red and to intensify the fright of the middle classes as to the danger of revolution, and swept the polls. It returned with a reconstructed Government based upon a reconstructed Party, a shattered Liberal Party, and a Labour opposition reduced in numbers and literally pulverised politically. It was truculent and confident in its political power over its opponents. It had used the “democratic” apparatus to the utmost and gripped it unscrupulously and effectively. It secured 48 per cent. of the votes and secured 68 per cent. of the seats in Parliament. The Liberals secured only 18.1 per cent. of the votes and 6.5 per cent. of the seats. Labour secured 33.8 per cent. of the votes and 25 per cent. of the seats.

It then set about the task of relieving the class which it represented. In its first budget it relieved them of £42,000,000 of taxation, cut down relief to the unemployed, and introduced harder conditions for the securing of unemployed benefit under the Insurance Act. It then began on a vigorous imperialist campaign as the “solution of unemployment and the means of trade revival.” It continued the efforts against currency inflation and reached the point of returning to the gold standard, which had the immediate effect of initiating a campaign for the reduction of wages and the lengthening of the working day and the week. Against this only the trade unions remained as a direct means of struggle.

Now let us observe the effect on the working class movement through this same period and get the measure of its development to face the new phases of the industrial crisis which, even with all this intensified political development by the Conservative Party, still remained as acute as ever. (Indeed during the year 1925 imports increased by £45,000,000 and exports declined by £28,000,000.)

In three years from Black Friday, 1921, the trade unions lost three million members. But the vast awakening of the workers in the great industrial struggles found its reflex in increased attention to parliamentary activities. In 1918 only 2,244,945 votes were cast for Labour. In 1922 the number had risen to 4,236,733; in 1923 to 4,348,379; in 1924 to 5,551,000. Here is distinct evidence of a class finding its feet. Especially are the last figures eloquent of this when it is remembered that the increased vote was secured amidst the denunciations of the Labour movement as a Bolshevik movement. It may be argued that these figures illustrate the movement of the middle class forces towards Labour, but without underestimating the force of this argument, an exanimation of the distribtuion of the Labour vote will show that its growth and strength correspond to the concentration of population and industry and emphasises the awakening political consciousness of the working class.

Lest it be thought that I am overlooking or underestimating the movements of the middle classes we will examine the movement of social forces in relation to them also. It will be found that their movements and their economic position emphasise the process which is here being portrayed. Throughout the period under review there has been a continuous concentration of wealth which is arresting in its significance. According to the Labour Year Book, 1926, the income tax returns show first that:

“The aggregate income of the income-tax paying class has declined very little during the recent “lean years” . . . . The aggregate income of income tax payers is actually greater in 1923-4 than it was in the prosperous year of 1918-19, when it stood at £2,071,571,796; while this larger income is distributed among a smaller number of taxpayers than was the income of 1918-19. Thus in 1918-19 the aggregate number of individuals estimated to have incomes over £130 per annum was 5,747,000 of whom 3,547,000 were effective taxpayers; but in 1923-4 though the aggregate income of income-tax payers is greater than it was in 1918-19, the number of individuals with incomes of over £130 per annum is estimated at only 5,000,000 and the number of actual payers at 2,400,000.

Let me add to this the fact that although in the 1925 Budget the super-tax was reduced considerably, the amount recovered from the super-tax payers was greater in 1925! A loss to the revenue was expected of some £6,700,000. Instead of the loss there was an increase of £5,000,000. These facts prove incontestably the concentration of wealth into fewer hands and the decline of the wealth of the middle classes.

The second feature of the income tax returns relates to the higher paid workers and points to the breakdown of the “Labour aristocracy.” The same year book proceeds:

“The decline in the past five years in the income of weekly wage earners liable to income tax has been much greater than the decline in the income of the income tax paying class as a whole. Thus in 1919-20 the aggregate income of weekly wage earners assessed to income tax reached the record figure of £825,786,395. By 1923-4 it had fallen to £300,000,000, a drop of nearly 64 per cent. The reduction in weekly wage-earners’ incomes liable to income tax since the maximum year of the boom has been more than 4½ times as great in proportion as the drop in the aggregate income of the whole income taxpaying class.”

Equally eloquent of the savage onslaught that has been made on the position of the skilled workers, especially when placed in relation to the position of the unskilled worker, is the Coal Commission’s Report. This confirms the evidence of the income tax collector and adds that proportionately the skilled workers, especially in exporting industries, engineering, shipbuilding, cotton, iron, steel, iron mining and pottery, have been reduced to an average of 40 per cent. above pre-war standards, whereas the unskilled workers retain an average of 70 to 80 per cent. above the pre-war standard. The cost of living index figure is about 75 per cent. above pre-war. (This evidence is brought out to justify the demands for the reduction of the wages of the miners, especially the higher-paid miners.) To this must be added the fact that it is precisely in these industries that the revolutionary movements within the trade unions have developed and the Communist Party has its greatest strength. It is precisely the General Workers’ Organisations that remain the most conservative, and it appears from these figures that there is good reason for it. Thinking themselves very fortunate because they have not been so heavily hit as the skilled workers, they are susceptible to the blandishments of leaders who explain this to be the result of their virtuous policy of industrial peace. But the arresting question forces itself upon us, “If the attack upon the better paid workers has produced such a far reaching effect, has so profoundly changed the relation of social forces that a general strike has been the sequel, is there any likelihood of this process coming to a stop when skilled and unskilled alike receive the shattering blows of a ruling class determined to surrender nothing further of its resources?”

The extent of the transformation in the voting of the masses we have now shown along with the economic changes in their position which laid the foundation of the change. While the parties were undergoing their internal changes in 1923 and 1924 and especially during the period of the Labour Government there was a lull in the attack of the employing class. Indeed a number of concessions were allowed to come through the Labour Government which encouraged the recovery of the trade unions. With the passing of the Labour Government the trade unions had to face a new situation, arising from disillusionment as to what they were likely to get from a Labour Government and the fact that they were again face to face with a better organised and more militant opponent.

But in arriving at this position some remarkable inner transformations had taken place. The rise of the Communist Party had proven to be more than an accidental passing phenomenon. From 1920 it set the pace in every manifestation of working class activity, focussed the leading questions of the working class as a whole and played an immense role in crystallising the class consciousness arising from the incessant struggles that had set in. On its initiative three definite movements had been organised and concentrated upon the problem of giving the working class a centralised class leadership corresponding to the class leadership and organisation of its exploiters. First the Unemployed Workers’ Committee Movement; second the Minority Movement within the trade unions; third the development of the already existing Trades Councils. All these movements converged upon the General Council of the Trades Union Congress. Their influence can be measured by the fact that the most recent conference convened by the Minority Movement represented a million workers.

There is no need to repeat the numerous issues and-campaigns that have been conducted on current politics. Sufficient to say that the issue of Communist policy versus class collaboration has become the predominant issue in the working class movement. But the Communist Party has not yet secured the organic leadership of the Labour Movement, with the result that the crisis of this period finds a working class, in the process of being revolutionised, facing class battles cumbered with a leadership that does not want to fight.

We have now established (1) the breakdown of British capitalist economy. Five years’ efforts at the expense of the working class shows no basic improvement. On the contrary, the facts tend to show the crisis as acute as ever. (2) Accompanying this breakdown there has gone on an intensifying process of class consolidation, a dividing of the social forces into two class war camps. (3) The ruling class, being more class conscious and experienced in politics, re-assembles its leadership in the hands of its most conservative party and strengthens its political dictatorship. (4) The working class increasingly awakens to political consciousness and rapidly begins to crystallise a new leadership based upon its class interests. (5) The change from the former privileged position of the skilled workers in the dominant British industries accentuates the process of developing class action and the growth of a new leadership.

I have refrained from showing the great influence of the Russian Revolution, of the campaigns for international trade union unity, of the foreign politics of the various governments, of the effects of imperialism and many other forces in developing this process, in order to demonstrate more completely that this evolution of social forces it not an imposition either of the gods or of some external propaganda, but is inherent in Britain’s internal conditions and her own social forces. With these things well established as the foundation for the wide support to the miners on the one hand and the irreconcilable ferocity and alarm of the ruling class on the other, we can direct special attention to the mining industry which dominates the fortunes of British economics to-day.

It is difficult to believe that the Coalition Government of 1919 intended anything more than to use the Sankey Commission as safety valve. In view of the claims of the miners’ opponents that they are impatient, it is well to take note of the principal findings of that Commission of seven years ago. It declared:

“Even upon the evidence given, the present system of ownership and working in the coal industry stands condemned, and some other system must be substituted for it, either nationalisation or a method of unification by national purchase and/or by joint control.”

It recommended nationalisation of mining royalties immediately, the adoption of the principles of State ownership of the coal mines and along with it a scheme to come into operation within three years, paying a “fair and just compensation.” But nothing was done, although it was quite evident then and has been evident ever since, that the coal industry was in such condition that without drastic changes it could not keep pace with the demands that were being made upon it in the markets of the world. This is fully confirmed by the present Permanent Under Secretary for Mines in the Coal Commission Report of 1926. He says:

“Ever since the end of 1920 the depression that then overtook the other heavy industries has been lying in wait. for the coal mining industry, but has been warded off by a series of accidents. For the last half of 1921 the industry was busy filling up the gaps made by the three months stoppage in the summer of that year. In the first half of 1922 the depression actually laid its hands on the coal mining industry, but the great strike in the United States of America came to our rescue. After that came the French occupation of the Ruhr, and it is only during the last fifteen months that the industry has not been helped by the temporary cessation of some normal sources of coal supply. Without this its present difficulties could hardly have failed to come upon it four years earlier.”

Two things are here established irrespective of all argunients re world competition. First, the need for reorganisation acknowledged seven years ago. Second, the employers and successive governments have been conscious of the artificial position and nothing has been done towards improving it. Nevertheless coal owners have continued to extract considerable profits during the same period from coal getting alone (i.e., leaving on one side profits derived from by-products which are estimated at £6,000,000 per annum).

|

In 1919 Profits amounted to In 1920 Profits amounted to In 1921 Profits amounted to In 1922 Profits amounted to In 1923 Profits amounted to In 1924 Profits amounted to Total Profits in six years |

£30,400,000 £35,000,000 £21,300,000 £10,403,527 £26,148,715 £13,419,057 £94,071,299 |

This is not what one would call a bad return on the money invested in the industry, considering that the total amount invested including “watered capital” amounts, according to the evidence in the two coal commissions, to £198,000,000. If we add to these profits the profits of the four years preceding 1919 we find that the total profits received in ten years amount to no less than £200,471,299. And they still own the mines.

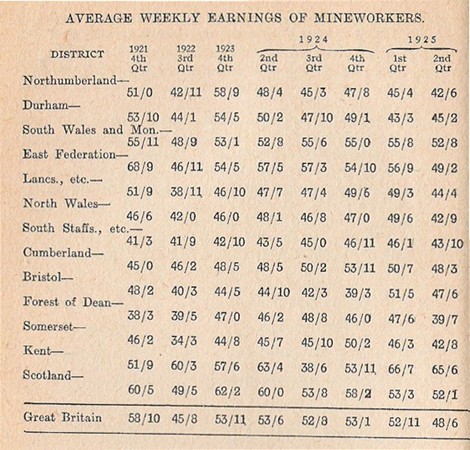

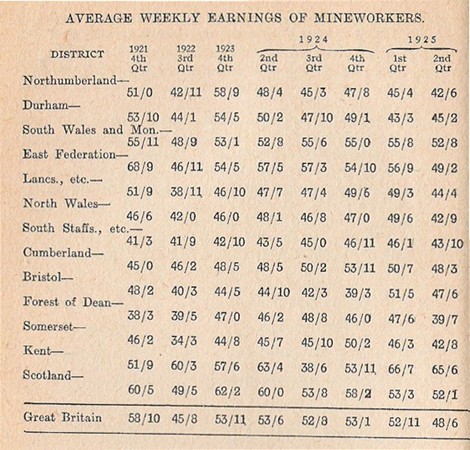

And how fared the miner during this period? The following figures published by the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain tell the story of the wages received.

The average wage of the mineworker in Britain in the first quarter of 1921, that is, before Black Friday was 89s. 8d. per week. A comparison with the above shows an average drop of 34 per cent. in the first nine months of 1921. A further comparison with wages of workers in other industries shows also the average wages of the miners to be lower than the wages of the workers even in the most depressed industries.

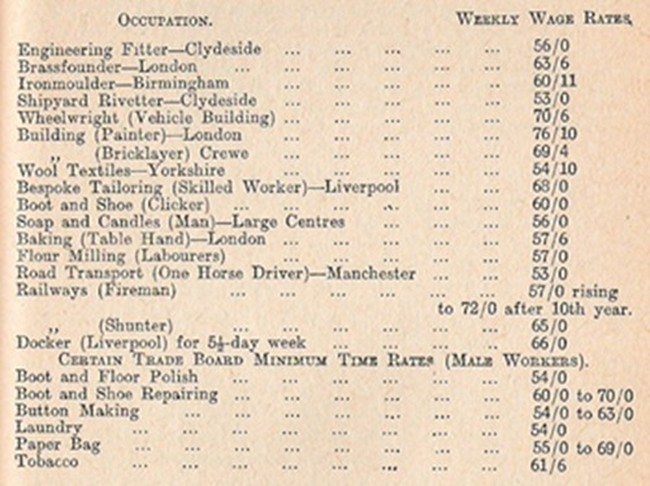

According to the evidence of Mr. Varley, the leader of the Nottinghamshire Miners (a Right Wing Labour leader now proposing that the miners should accept reductions), before the Coal Commission:

“It will be seen” he said “that even in the depressed ‘export trades’ the workers received a higher wage than the miners during the second quarter of 1925. Wages in many of the Trade Board trades, even, soar far above this figure and in very few of these one-time sweated trades does the rate of the lowest grade of unskilled male labour fall below this figure. We point this out in order to show that although the workers in these other industries are in no case getting an extravagant wage and in most cases are getting a very low wage, far too low to maintain a decent standard o€ living, the miners are worse off than them all, and are far below any decent minimum of subsistence. Many thousands of miners are getting less—considerably less—than even the low average of 48s. 6d, per week.”

(Note.—Trade Boards were established by the government some years ago, in those industries where the workers were badly organised or had no organisation at all, to do away with what was known as “sweated labour.”)

According to the “Labour Gazette” (a Government publication) of June 30th, 1925, the wage rates in various industries were as follows:

If the miners’ case rested alone upon the comparisons of wages and profits then the figures here given present an overwhelming case against the mineowners, and warrant the workers rendering the miners every possible support. But the miner invests his life in the coal-getting business, and takes risks that are far greater than the risks taken by other workers. Who ever heard of a mineowner risking his skin in the service of the industry? The evidence of Mr. Hartshorn, a South Wales Miners’ leader, before the Sankey Commission remains true to-day as then. On this occasion he gave the following vivid description of the hazardous nature of the miners’ calling:

“I do not think the public realise that one out of every six or seven—certainly one in every seven—of all the men and boys employed in the industry, surface and underground, every year get injured to an extent that renders them idle for at least seven days, and a very considerable number of them, of course, are rendered idle for a much longer period, and a large number of them are totally and permanently disabled. I think about four men are killed in the mining industry every twenty-four hours, Sundays and week-days. This is an occupation in which men are blown to pieces . . . In the mining industry the casualties are more like those of a battlefield than anything else. The only difference between the soldier and the miner is that the miner can never ask for an armistice. He cannot even treat for terms of surrender. The casualties go on every day.”

In three years, 1922-3-4, 3,603 miners were killed and 597,195 were injured. An injury which does not keep the worker from his work for at least seven days is not recorded in the statistics.

In view of the effective returns which the mineowners have received for their “monetary risk” and the appalling contrast in the character of the risk taken by the miner, and the poor monetary results he gets in return, one would expect some compensation in other directions. But such is not the case for the British miner. It is questionable whether there is another large class of workers who have to live in the abominable conditions of the miners. When he returns from the semi-darkness of the pit, his clothes covered with coal dust and often wet through with working in water or, under a dripping roof, the miner has to wash and change in the room that in many cases has to serve as kitchen, wash-house, scullery and bedroom. Often he has to walk miles before he can get to even this accommodation. Pit head baths are a rarity in Britain.

As for the housing conditions in general, apart from say the Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Notts coalfields, which are newer and more up-to-date, they are an abomination. This was acknowledged by the Government Commissioners so long ago as March, 1914, when a special investigation was made. It was acknowledged again by the Sankey Commission in 1919. But a Liberal investigator, a Mr. James, bears witness that in spite of all the acknowledgments and investigations, nothing has been done in many of the districts up to 1924. He says:

“I have personally investigated all the specially bad slums which were visited by the Commissioners as long ago as March, 1914. All of these, condemned long ago, are inhabited to-day—generally more densely inhabited—and there is not a word of condemnation applied then that could not be applied now.

“At Merry’s Row, in Blantyre, I found a slum containing single roomed backless bungalows in which whole families live.

“In the same neighbourhood, close to the birthplace of David Livingstone, is a dilapidated square known as “the village,” densely inhabited by miners. It was built more than 100 years ago.

“At Rosehall, on the outskirts of Coatbridge, I found nearly the worst of all.

“Rosehall is an odious, hypocritical place-hypocritical because the outside of the outer row along the main road has been touched up so that it wears a rather picturesque, old-world appearance.

“But pass through this outer husk by one of the narrow passages, and you find yourself in an enclosed area of rows of low cottages, with rows at right angles to them at the ends. Some of them have two rooms. Some of them are one-room, without back exits or windows. Others are one-room, back-to-back.

“In each of these single rooms lives a miners’ family. There is no pantry. The coal is kept under the bed. Water has to be obtained from a standpipe outside, used by a number of houses. Conspicuously huddled together in the yards are filthy huts for sanitary purposes,”—(“Coal and Power.” Lloyd George Report.)

Certainly this is a picture of a bad patch, but apart from the districts which I have mentioned as distinctly modern, all the other relining districts are bad patches. The typical mining village is an atrocity. The dwellings have been thrown up at a minimum cost in long rows-mean box-like affairs, which soon fall into disrepair, soon become black and grim as the mines themselves, making the lives of the miners’ wives into a wretched slavery. The normal accommodations of the towns are denied them, and the lack of decent accommodation for the miners at the pit-head piles on the agony of keeping pace with the dirt.

And this is the life of the mining population in the pit and out of it! The miners risk life and limb in the getting of coal for a pittance. Their wives face the agony of making the pittance go as far as is humanly possible and battle incessantly amidst domestic conditions that are awful to think about. And the children? . . . .

Here then is the economic and social foundation of the struggle in the mining industry, which developing with the struggles embracing the rest of the British nation, led to the General Strike. The mineowners demand a continuation of their profit making, come what may to the lives of the miners. The miners fight for the means of life. After three years following upon the Black Friday debacle, the miners secured in negotiations conducted during the period of the Labour Government a slight improvement in the agreement forced upon them in 1921, and an open struggle was avoided. But it was a short agreement, due to terminate in March, 1925. It was at this point that the miners’ struggle converged with the general struggle. The Miners’ Federation felt after the experience of 1921, when every trade union had been taken separately and beaten, that the working class movement would not want to repeat that experience. No leaders dare propose that the miners should accept either lower wages or longer hours. Indeed so strong had grown the resentment within the working class against the capitalist wage cutting offensive that the Trades Union Congress pledged itself to resist any further attacks on wages or hours of labour. It was thus that the forces converged upon the path that led to the General Strike.

Next: III. “Red Friday” and the Nine Months’ Truce