T. A. Jackson & R. W. Postgate

Source: The Communist, November 5, 1921.

Publisher: Communist Party of Great Britain

Transcription/Markup: Brian Reid

Public Domain: Marxists Internet Archive (2007). You may freely copy, distribute, display and perform this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit “Marxists Internet Archive” as your source.

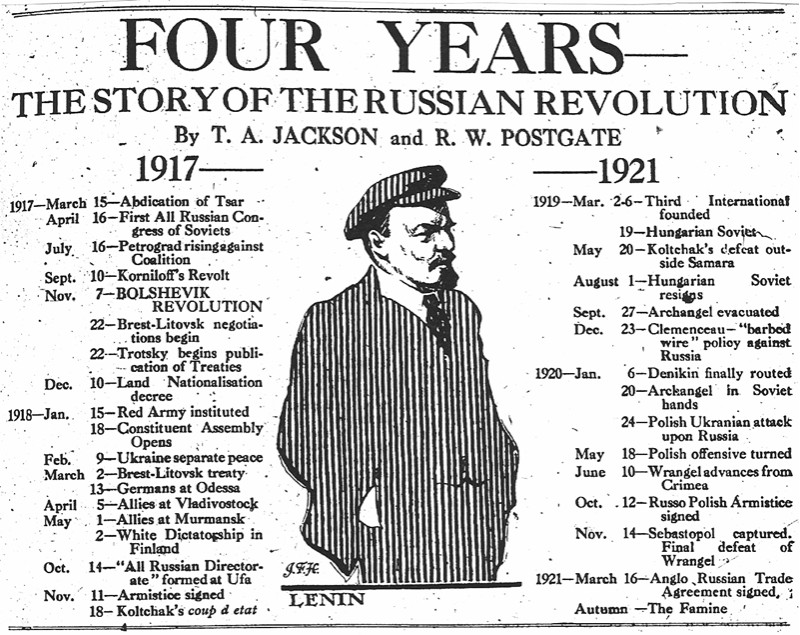

ON November 7th 1917—four years ago!—the impossible happened. The organised workers of Russia, acting through the All-Russian Congress of Workers’ Councils (Soviets), and led and inspired by the Communist Party (the “Bolsheviks”), declared themselves the ruling authority of Russia, making good this declaration by deeds with whose echoes the world has been ringing from that day to this.

Till that day all the learned ones of the earth had convinced themselves and most of those whom their teaching could reach that such a thing was impossible. The workers, they said, were too ignorant, and too undeveloped to do any such thing as rule.

The workers, soldiers, and peasants of Russia have refuted their theories, and confounded their wisdom. That the workers once they bring themselves to the point of making the attempt, can make themselves rulers of the State, and can retain power and control in spite of all that can be done against them—in spite of war, invasion, insurrection, assassination, economic exhaustion, sabotage, calumny, and intrigue—that the workers can hold their own if they have but the necessary will, the Russian Workers’ Revolution has proved past all possibility of question.

On this, the fourth anniversary of their triumph, the Workers of Russia stand faced with their last and greatest foe. By the end of 1919, they had beaten off the attacks of the Allies and of the Germans. By the end of 1920 they had overthrown and destroyed the armies of the counter-revolutionary adventurers who one after the other sought to bring them again beneath the yoke of Capitalist Imperialism. Alexeyeff, Korniloff, Kolchak, Denikin, Von der Goltz, Petliura, Dutoff, Yudenitch, and Wrangel—one after the other they broke and scattered, smashed against the impregnable solidarity of the armies of the Workers’ Soviet Republic. They have broken through the “barbed-wire fences” of Clemenceau. They have pierced the blockade set up by the Curzon’ and the Churchill’s. They have out-worn the lies and the pretences of the Miliukoffs, the Martoffs, the Kerenskies, and the rest of the allies of plunder-imperialism. All this they have done.

In doing this they have spared neither strength nor effort, life, nor limb, nor health, nor rest. All that men can give—courage, self-sacrifice, devotion, heroism, unremitting toil, heartbreaking privation—all these the heroes of the Russian Workers’ Revolution have given, and given without stint, to save for mankind the splendour of hope embodied in the fact of a Workers’ Republic triumphant over the assaults of that hideous Capitalist Imperialism which still holds the rest of the world in its grip.

Wearied and spent with toils incredible and victories unmatched, they, on the fourth anniversary of their initial triumph, face the horrors of famine.

No fault of theirs—a natural calamity made inevitable and intense by the villainy of their foes has brought them to this pass. They stand, these heroes of the most magnificent effort in the world’s history, all but exhausted before a tragedy so vast that even their foes are appalled.

In the hope that even at the eleventh hour, the workers of Britain may be roused into action that will lessen their affliction, and lift from them somewhat of their burden, we tell again the story of what they have done. What they have done, not for themselves only, but for me and for you—for us and for all who toil and suffer in any part of the earth.

BEFORE 1914 no Government had been thought more unshakeable than that of the Tsar. The peasant and working mass whom it exploited and the general intellectual class whom it subjected seemed either too ignorant, and debased or too disunited to offer any serious resistance to its rule.

When, therefore, in March 1917, the news came that the Tsar had fallen—had abdicated—it reached the greater part of the world with the suddenness of a thunderbolt.

Two-and-a-half years of war had brought to Russia nothing but collapse. There was truly an enormous army raised by the conscription of the working and peasant masses. But to equip this army required a greater number of wageworkers than had ever been gathered into the towns of the industrial north. To feed these masses, at a time when the peasant population had been depleted, as never before, was a problem. The peasants, were hard pressed to produce the food. The railway systems, choked with men and materials for the armies broke down before the task of delivering it to the towns. Steadily, in spite of Allied subsidies, the Tsarist system staggered to its collapse.

The army was either without rations, or boots, or rifles, or ammunition. The towns were without food. A great effort in 1915 to meet the oncoming German onslaught had meant the withdrawal of men and material from essential domestic production to meet the military emergency. When the wave of artificially generated enthusiasm passed it left the whole population faced with the fact that the armies, devoid of essential equipment, were beaten, disorganised, and demoralised. The towns were starving for want of food; the peasants were mad with discontent from the burdens of war and the lack of means to get their produce to market; the railways had all but entirely broken down. The whole civil and military service knew that (were they only free to give their full strength to the task) the German Imperialist armies could sweep over Russia. Tsardom was powerless to resist.

The end came in an unexpected form. The heads of the Parties in the pseudo-Parliament (the Duma—which had been hastily summoned to devise means of coping with the crisis) had begun to concert measures for taking in hand the direction of the State, when a quarrel in a Petrograd food-queue between the workmen’s wives and the Tsar’s police grew into a scuffle, and that into a pitched battle. Troops sent for to aid the police revolted. Fired by their own discontents, the guards took the side of the people. The police were hunted from the streets, and its material defences shattered as its moral supports had been undermined, Tsardom collapsed into nothingness. The Tsar abdicated, was arrested, and disappeared. Nicholas II. passes from the page of history so completely and so ignominiously that to this day few can tell with certainty what was his final fate.

With the Tsar out of the way the problem was who would rule in his stead? The answer to that question might have been divined beforehand from the nature of Tsardom itself.

Given a country in which an enormous mass of peasants had been for time out of mind compelled to endure all the rapacity of the local grand-dukes, barons middlemen, and tax-collectors; and in which the elaborated enterprises of foreign capitalists had aggregated a large proletarian mass and in which, moreover, a numerically large but relatively small intellectual population had been cut off by the very nature of Tsardom from any hope of social advancement except on terms of the most abject submission to the secret service machine, it was inevitable that there should be available as a moral authority capable of replacing the authority of the vanished Tsardom nothing but such institutions as were set on foot by the peasants and working masses themselves.

In the rural districts the peasants had for centuries been accustomed to the village meeting—the convocation of heads of households—the rural commune. In the towns the workers, under pressure of Tsardom, had evolved in place of the more familiar trade-unions of Western Europe, a secret system, more or less elaborate, of workshop councils, whose delegates would on occasion form a town or district council. The capitalists, the middle-class, the professional men had all been prevented from open organisation by the Tsarist system. When that fell away the only real authority left in Russia was that of the Councils of Workmen and Peasants and their counter-part, the Councils of Soldiers and Sailors, which had been set up in the army and the fleet by the conscript levies who had had experience of the former.

Men are slow to break ingrained habits. Not until November did the working mass of Russia realise the vastness of the change that had come, and the need for the setting up of a new authority. From March when the Tsar was forced to abdicate—while his secret police were hunted like rats over the roofs and through the cellars of Petrograd—until November, the time was filled with a series of attempts to set up one or other imitation of the various sorts of Government which found favour in Western Europe. Limited Monarchy, Constitutional Monarchy, Authoritative Republic, Democratic Republic—each had its turn. At first the working mass, in Petrograd and elsewhere had so little confidence in their own powers that they invited the leaders of the old pseudo-Parliament, the Duma, to form a Government. When these failed, an attempt was made to establish a Coalition of the leaders of the more popular parties. When this in turn failed, and it became clear that the mass of the people were sufficiently roused to make it necessary to consider them, a Government headed by a one-time leader of the Peasant Party—a sort of Socialist, Alexander Kerensky—was set up. When he failed, as his predecessors had done, the only power left that could at all rule or direct Russia was that of the spontaneously evolved Workers’, and Soldiers’ Councils.

To interpret this succession of failures rightly it is necessary to remember alike the task before each would-be ruler and the means available for its solution.

Russia of the Tsars was a grotesque social system—a fossilised feudalism into which the influx of Western Capitalist enterprises had brought a discordant and disruptive influence.

The mass of the population in the South, and Eastward away across Siberia were interested in agriculture either as peasant holders, land workers, village-craftsmen, middlemen dealers, or land barons. The vast majority of the innumerable acres of Russian land were the property of either the Imperial Court, the Church, or the land-owning nobles. Some three-quarters of the land were owned directly by one-tenth of the population. The mass of the population had to be content with the fraction that remained. The congestion, the land-hunger, was made unendurable by the expansion of the population on the one side and the crushing burden of taxes, labour-rents, payments in kind, or in money, into which the old feudal rights of the aristocracy had been transmuted—on the other.

In the north were the great industrial centres for the most part the promotion of West European capital. Into these towns m addition to their permanent population came regularly masses of the peasantry forced to eke out the scanty produce of their inadequate land holdings by a period of wagelabour in the factories.

Economically Russia was an aggregation of rural producing communities in every conceivable stage of development, each exploited directly by a dominating local land baron, and each by force of poverty and constraint of the local agent of Tsardom kept mentally and morally separate from every other like community in Russia.

Super-imposed upon this basis was the bureaucratic hierarchy of Tsarist rule and repression; to all the more profitable posts in which the aristocracy alone were admitted.

Thrust into the arbitrary structure were the various capitalist concerns—islands of capitalist economy in an agrarian sea—and their reaction upon Tsardom was such as to at one and the same time give a motive for more intense rapacity to the ruling hierarchy (since the gains of feudal plunder could be magnified by capitalist increase) and provide (in the proletarian solidarity leaned in the workshop and the widened outlook of the towns) a means for their overthrow.

The Revolution came with the towns clamouring for bread, the peasants hungry for land, and the (whole, working and peasant mass clamouring or peace. But it was one thing to say peace and another to make it. Should Russia isolate itself from its Allies and make a separate peace—getting the best terms possible from the Central European Alliance?—if any but ruinous terms could be got from the Central Powers. Or, seeing Russia’s dependence upon the Allies for immediate necessities, and its financial indebtedness to them, would it not be better to make a bargain with them in which in return for material aid in the economic re-establishment of Russia, the newly emancipated nation, returned with vigour and zeal to the attack?

In plain English—should the new Russian State purchase peace with the sacrifice of territory and risk the enmity of the Allies, which that would entail, or should it shoulder the burden of war in return for aid in food, materials, and finance?

The answer to these questions was prompted, in the absence of concrete information by class-emotion. The well-born and well-to-do leaders of the Duma whose “Liberal” outlook envisaged nothing further than an establishment of the counterpart of Western Capitalism the intellectual middle-class who looked merely for a breakdown of the old aristocratic monopoly of the higher and better-paid offices of state or a removal of the Tsarist restrictions upon literary productivity; the domiciled agents of Allied capitalism and finance—all these were with little hesitation for an understanding with the Allies, a thing made inevitable to them by their indebtedness to France and Britain.

The peasant mass almost without a dissentient took a view determined by the personal experience of their sons and brothers in the trenches. At all costs the war must end.

The industrial workers took the clearest and loftiest view. They saw in the situation a chance to do two things: to end the war and extend the revolution into a world-wide triumph for the working class. The Petrograd Soviet early in May, 1917, summoned by wireless an international Socialist Conference to meet in Stockholm to devise measures to enforce upon the contending States a peace on the basis of no annexations; no indemnities; self-determination of subject peoples.

This was done quite over the heads of the Provisional Government, whose authority at that date depended not so much in its personal powers or its command of public approval as upon the unwillingness of the Petrograd Soviet to assume the direction of affairs itself. But although unwilling to take responsibility until its power throughout Russia and the army was more clearly manifest, the Petrograd Soviet did feel itself competent to act as a spokesman for the Russian Working-class to their fellow workers in all lands.

Simultaneously there was developing the effects of a previous act. At the outbreak of the Revolution in March the Petrograd Soviet had issued a call to the soldiers of the Petrograd garrison demanding that they obey only orders countersigned in their name. This call was later extended to the army, and concerted efforts were made to keep in being every batallion over which the Soviet could exercise am influence—and to organise their fraternisation with the troops opposed to them.

There were, in fact, two Governing Authorities in Russia: the Provisional Government, set-up by the Duma, and the System of Soviets which sprang into being throughout Russia—in the fleet, the army, the workshop, the town, and the village—in spontaneous imitation of the example of Petrograd. The former Authority commanded the respect of the privileged and educated classes. The latter that of the masses. Neither felt strong enough, at first to dispute the authority of the other: each saw that the division of power was an anomaly that could not last for ever. Both agreed that a National Parliament—a “Constituent Assembly”—would have to be elected to decide upon a constitution for the new Russia; and pending its assembly each Authority prepared to tolerate its rival with the best grace it could summon.

The provisional Government appointed its nominee in every district to replace the functionaries of the Tsar—the local Soviets forming spontaneously to support the revolutionary authority so long as there seemed any danger of resistance to his installation. There appeared a possibility, such was the enthusiasm of all classes for the revolution, that if the calling of the Assembly could only be deferred for long enough the official hierarchy of the provisional Government could be elaborated into a system, so well established that it might become a permanent order. Normally, there is little doubt that this is just what would have taken place. Actually, the facts of the war and internal collapse demanded something quite otherwise. These questions had to be tackled: Peace, Bread, Land. When the Petrograd Soviet took the initiative in a call for a peace on the basis of annexation nor indemnities, the nominal Authority of the Provisional Government received a challenge. The diplomatic representatives of the Allies (having in mind the various treaties between them which this demand would abrogate) promptly pressed for its repudiation. Miliukoff gave the requisite assurances and fell before the blast of popular indignation; a Coalition Government was set up in which were included leading representatives of the parties which had come to dominate the Soviets—the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. For a few weeks the Government temporised and then feeling itself secure in that the Soviets under the domination of Parties convinced of the need for the co-operation of all classes were in no mood to challenge their authority—gave way to Allied pressure and ordered the armies to resume the offensive. The effect was electrical. Soviet after Soviet raised its protest; workers soldiers, peasants, the intellectuals of the border nationalities all raised a clamour of protest. Men on leave refused to return to their units: garrisons refused to march. In Petrograd a mass of soldiers who had been released for field work were ordered to join their units at the front. Mad with fury they paraded the streets in company with workmen from the factories, and a machine gun corps. Outside the Soviet offices they paraded demanding that the Soviets take over power. The Soviets, dominated a “Democratic Block” hesitated and finally did nothing. The demonstrators, after halting all night, finally dispersing. Similar outbreaks took place in various parts of Russia. All of which, however, were suppressed by troops loyal to the Government. The insurrection was spontaneous and unorganised. One of its first acts was to parade before the Headquarters of the Bolshevik Party and demand their aid. This was with some hesitation given; and the opportunity was seized by the new head of the Provisional Government, Kerensky, to suppress the Bolshevik Party.

This rising of the extreme Left was barely over before another attack was made—from the extreme Right. Korniloff, a Tsarist general, with a number of picked regiments, marched upon Petrograd, using the above recounted incidents as an excuse, to “restore order.” After some ambiguous parleyings Kerensky declared against him—while the workmen of Petrograd spontaneously mobilised and defeated him. The circumstances of his defeat made obvious to all that the army itself was split in twain along the lines of class-division. The rank and file were (acting through their committees) supporters of the Soviet as an institution: the officers stood for the Provisional Government.

The increasing misery, the steadily accentuating food shortage, the failure of the Government to promulgate a law giving the land to the peasants: the refusal of the Allies to entertain the notion of peace on the basis of “no annexations and no indemnities,” all together brought matters to a head. Every “superior” class in turn—aristocrats, bourgeois, intellectual middle class—had tried. None had been able to devise a programme or command the respect of the aroused and suffering mass. There remained alone the mass itself, and the hour was approaching when they were to take their courage into their own hands and assert themselves as the rulers of their own destinies.

The party which we have learned to call the “Bolsheviks” was originally the advanced wing of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. Little if anything in their general theories divided them from the other wing of that party—the Menstieviks. Their differences arose over matters of vital policy. The Mensheviks, while in principle accepting the rule of the Worker as an end to be reached, in practice sought invariably to delay or avoid putting the principle into operation; seeking always to effect a transitional agreement with the “progressive elements” in their classes, on the supposition that thereby the workers would become sufficiently enlightened to be entrusted with power.

The Bolsheviks, on the other hand, acted always on the principle that the workers would learn to rule, by ruling—that the nature of Capitalist Society was such as to constantly indoctrinate the worker with the notion of his own class inferiority; a doctrine which the practice of co-operation with the superior classes, however “progressive” only served to make inveterate.

Both parties—or to be more correct, both wings of the Social Democratic Labour Party—and with them the other Socialist Parties of Russia were, under the Tsardom, necessarily secret societies. At the outbreak of Revolution in March, their leaders were in exile, or in prison. With the new era began the open agitation and organisation of these Parties, and each Soviet became a theoretical battleground for the contending forces. The peasant areas in the main were the stronghold of the Social Revolutionary Party—a Party which even then tended to split into two wings resting on the basis of the richer and poorer peasantry respectively.

In the towns the intellectuals and professionals were attracted to the Mensheviks; the workmen and labourers to the Bolsheviks.

With the political excitement of the March days men and women of all classes below the richer bourgeoisie began to take an interest in the work and organisation of these parties. The intellectuals in particular, with careers to make, became engrossed in the struggle for power. There, grew to be an immense number of “March” Socialists and these for the greater part became allied to the Menshevik or Right-Social Revolutionary Parties.

At first the influence of the Bolshevik Party was considerable. They were not dominant, their leaders being in exile and their organisations all but non-existent. Still, their ideas expressed at second-hand through the Petrograd Soviet gave the first rallying cries to the revolution. With Tsardom fallen came, as we have seen, a period of the general co-operation of classes. In this atmosphere there was no room for the irreconcilable class consciousness of those who pinned their faith to the dictatorship of the working mass—the proletariat. So that although the Bolsheviks grew in numbers and influence they relatively declined before the superior growth of their rivals. With the establishment in April of the All-Russian Soviet Executive in which the Mensheviks and Right Social Revolutionaries dominated, the Petrograd Soviet, now overwhelmingly Menshevik, passed into a period of decline. Suppressed officially by Kerensky in July, the Bolsheviks gained enormously in the esteem of the masses as every day revealed the truth of their predictions and the impossibility of any coalition of classes before the emergencies of war, famine, and land-settlement. As each locality more and more found itself—released from Tsarist restraints—an uncontrolled and selfcontained unit—as Russian Society more and more relapsed into a virtual anarchy—a condition which Anarchists of various schools applauded from conscientious motives, it grew vitally necessary for the very life of the working masses in the towns, and for the rank and file in the army and the fleet that some co-ordinating disciplinary force should be brought into play to save the whole of Russia from total collapse.

In Soviet after Soviet Bolshevik majorities began to appear. In Petrograd the Bolshevik majority decided to take the bull by the horns. After March they had at first clamoured for a speedy meeting of the Constituent Assembly. Then when, after various delays, the elections were announced, it was clear from the devices adopted by Kerensky’s agents to secure a majority that the meeting of the Assembly would bring not a legal establishment of the Soviets as governing instruments, but a counter-power which would fight them even more strenuously than the Provisional Government had done.

Since their July adventure the Bolsheviks had persevered with their slogan “All power to the Soviets.” The elections for the National Assembly were called for late in November. It was imperative that a Congress of Soviets should meet to decide upon an attitude towards the new authority. The Menshevik Executive declined to summon the Congress; the Petrograd Soviet (with its Bolshevik majority) summoned the Congress over the heads of the reactionary officials.

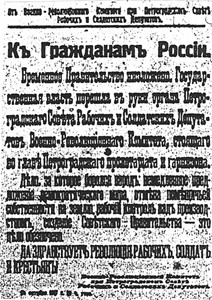

In anticipation of its assembly every preparation was made to transfer all power to the Soviets. A Military Revolutionary Committee was set up by the Petrograd garrison, acting under Soviet inspiration, and when sufficient delegates had arrived to assure the Bolsheviks of general support, the members of the Provisional Government (with the exception of Kerensky who escaped) were placed under arrest and all Russia and then the whole world learned that Russia had become a Republic of Workers’ Peasants’ and Soldiers’ Councils.

The All-Russian Soviet elected a Council of People’s Commissioners with Lenin as Chairman and Trotsky in charge of Foreign Affairs. It proceeded to appeal to the peoples and governments of all lands for a general armistice preliminary to the conclusion of peace on the basis of no annexations or indemnities.

It followed this with a decree abolishing private property in land and vesting the control of all estates thus confiscated in the local and district Soviets; and this a few days later with another similarly establishing workers’ control over industry.

The import of these decrees was to turn the rank and file in the army and the navy and the mass of the workers and peasantry into the collective agents of the Soviet State. When these local Soviets were further instructed to establish under their own control a militia of armed workers and peasants to enforce their decrees, the Soviet Power was ready to commence its struggle for existence.

THE appeal of the Soviet State for a general armistice was received with contempt by the Allies. Unable to believe it possible for a proletarian State to survive, and knowing the financial means at their disposal for influencing the intellectual and other classes, the Allies built all their hopes on the possibility of reaction.

The Central Powers, glad of a chance to score a propaganda point at the expense of the Allies, accepted the offer, hostilities were suspended on the Russian front, and the offer thrown open to all the Allies to make it a general Armistice. For a month the offer stood open and then seeing the hopelessness of further appeals in view of the complete press control of the Allied Powers, the Soviet Republic commenced negotiations for a separate peace.

The Soviet representatives tabled certain general principles of the proposed peace. It must be, they said, a peace without annexations and without indemnities. All negotiations were to be open and the results of each day’s proceedings were to be reported by wireless to all the world.

These proposals were accepted as a provisional basis, but it soon became clear that on the Imperialist side there was no serious intention of keeping to them.

The stand made by the Bolshevik negotiators and the effects of their propaganda among the German troops and, through them, among the German population, produced effects which had not been calculated upon. A series of strikes broke out in Vienna, Berlin, in Hamburg and all over Germany. Everywhere the Bolshevik appeal found an echo. The Imperialists found, to their amazement, that the passionate eloquence of Trotsky was not as they deemed the vapourings of an obscure fanatic but an expression of the passionate war-weariness of the workers of the world.

It was necessary to do something to counter the revolutionary solidarity of the Soviet Republic. The chance was presented early in the negotiations by the attendance of negotiators representing a parliament, which had been set up in the district of the Ukraine, under the inspiration of Kerensky. This anti-Soviet State had declared itself “self-determined” in accordance with the formula professed by the Soviet Government and with money advanced by the Allies on the security of its corn harvest had proceeded to hastily equip an army. Hardly was the bribe in their pockets before the opening of negotiations between the Central Powers and the Soviet Republic gave them a prospect of a still better bargain. Their plenipotentiaries attended the Peace Conference, and just when the dramatic methods of open diplomacy were producing their designed effect upon the proletariat of Germany the Ukrainian bourgeois came to terms and agreed upon a separate place. It is noteworthy that the “recognition” which the Allies have refused to the Soviet Republic was given freely to the Ukrainian Rada—to be used by them to negotiate a separate peace!

Thus deserted, the Soviet Republic made what fight it could. German militarism adopted its most swaggering tone. The internal unrest in Germany being for a time allayed, it seemed that Imperialism had but to demand and the Bolsheviks could but comply. They, however, refused. They could not continue the war—they made no pretence about it But sign a robber peace they would not. They non-plussed Imperialism by the unprecedented expedient of declaring the war at an end and leaving the Germans to do as they might. The armies of Germany accordingly marched into Russia; the work-people of the towns enlisted in masses to the Red Guards; frenzied appeals from the Soviet Commissioners to the Allies brought nothing but stony refusals of aid; and, deserted by all, the Soviet Republic was forced at last to sign the treaty of Brest Litovsk.

While all this had been happening, the forces of counterrevolution had been active.

Their first and most obvious course was to raise an armed force which would overthrow the Soviet authority. Kerensky, who, as we saw, escaped from Petrograd on the night of the Bolshevik revolution, fled straight to the Army, and persuaded General Krasnoff to lead his division to “deliver Petrograd from anarchy.” The courage and energy of the armed workers of Petrograd defeated this assault; Kerensky again having a narrow escape.

Infuriated by the Bolshevik decrees, the various dispossessed classes gathered in the borderlands of Russia to plan and recruit for the recovery of that which they had lost. Particularly in the Cossack territories were efforts made to raise anti-Soviet armies.

Kerensky had used the nationalism and bourgeois prejudice of the richer peasantry of the Ukraine to drive a wedge into the territory of Soviet Russia—careless whether the hand were that of Allied or German Imperialism so long as the blow was struck against Soviet Russia!

By the end of 1917—while the negotiations of Brest Litovsk still continued, the outlines of anti-Soviet powers became visible in the Cossack territories of the Don, Orenberg, and the Urals.

Alexeieff, formerly the Tsar’s Commander-in-Chief, gathered round him in the Don many old Tsarist officers, being assisted by Korniloff, who had already made one bid for military dictatorship. The revolutionary workers of Petrograd, Moscow, and the Donetz Basin, without military training or expert leadership, by sheer dash, defeated this army of the cream of Tsarist militarism. The workers from the Urals and the Volga defeated Dutoff. The Red Guard of Moscow and Petrograd defeated the troops of the Ukrainian Rada and took Kief—establishing the First Ukrainian Soviet Republic. Everywhere the fast armed assaults upon the Soviet power were repelled.

This, however, was only the first phase. After the Brest Litovsk treaty German forces marched into the Ukraine to collect the grain harvest for which it had bargained in the peace treaty. On the pretext that the frontier was inadequately demarcated they pressed on to Odessa and the shores of the Black Sea, and into the Donetz. Everywhere they drove before them the guerilla bands of the Red Guard, completing their work by setting up under their protection the rule of the Ukrainian landlords and the Tsarist General, Skoropadsky. Established in the Baltic provinces by the treaty of BrestLitovsk, the German Imperialists everywhere overthrew Soviets, slaughtered the Bolsheviks, and re-established the landlords. Passing on to Finland, they aided the suppression of the Revolution there, and the establishment of a White Dictatorship over the slaughtered ruins of the Finnish revolution.

These German operations in Finland gave the British Government an excuse for landing troops first at Murmansk, then at Archangel. The local Soviets were overthrown and an attack launched in the direction of Vologda. Simultaneously the Japanese landed at Vladivostock and the Czecho-Slovaks were persuaded to revolt. On the Don, Alexeieff being dead and Korniloff killed, Krasnoff reappeared at the head of the Cossack counter-revolution, being able to gain possession of the Don territory. Dutoff again raised the Orenberg Cossacks, and the Czecho-Slovaks in the Volga provinces captured Samara, Simbirsk, and then Kazan.

Corn granaries, the Donetz coal, the Baku oil, the Ural and South Russian iron, and the cotton of Turkestan—all were cut off from the Soviet Republic’s control. Everything seemed as hopeless as it well might be. A hope of relief came on the approach of the first anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. The people of Austria and of Hungary rose in revolt, and proclaimed Republics. The German fleet hoisted the Red Flag at Kiel, the German Revolution broke out, and in a few days the Kaiser had abdicated and fled. An armistice was concluded on November 11th, 1918, and the World War came to an end.

The hope that this gave of a World Revolution, which would make universal the accomplishment of the heroic masses of Russia, was soon dissipated.

The Soviet Republic at once repudiated the Brest-Litovsk treaty, which had given the Allies an excuse for their military attacks and their Press propaganda against the Soviet régime. The Allies at once refused any dealings with the “iniquitous” Soviet Powers. They “recognised” each successive “Government” which the various anti-Bolshevik parties set up—in the Ukraine, at Omsk, at Ufa, at Samara. They forbade the Germans to evacuate the Baltic provinces and used their utmost energies by blockade, invasion, and the subsidy of insurrection to bring about the Soviet’s downfall.

The collapse of Turkey had enabled them to introduce forces of men and munitions into the Caucasus region, and from there into the South Volga and the Don. Events were developing which enabled them to supply a mighty force which cut the Soviets off from Turkestan and Siberia, while in the North from Murmansk and Archangel, in the West from the Baltic Provinces and Poland, and in the South from Roumania and the Black Sea, their attack strengthened hourly.

The collapse of Turkey had enabled them to introduce forces of men and munitions into the Caucasus region, and from there into the South Volga and the Don. Events were developing which enabled them to supply a mighty force which cut the Soviets off from Turkestan and Siberia, while in the North from Murmansk and Archangel, in the West from the Baltic Provinces and Poland, and in the South from Roumania and the Black Sea, their attack strengthened hourly.

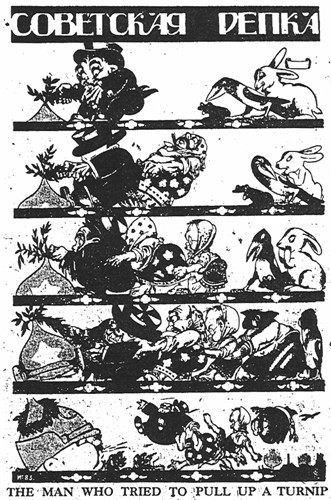

Civil war did not reach Siberia till the June of 1918. Up till then the moneyed and political interests opposed to the revolution were intimidated by the unanimity and justice of their opponents. They were under the spell of this moral victory for a period of some months, and it was not until the summer that it was generally realised that over large portions of Russia the revolutionary workers were unarmed and could not resist any group which had the hardihood to start violence and civil war in a peaceful population. What moral scruples they may have had were speedily overcome when a suitable instrument was found in the Czecho-Slovak troops. These were battalions which had been formed tinder the Tsar during the war, from Czech deserters from the Austrian army. When the peace of Brest Litovsk was signed, Chicherin arranged with Masaryk, the Czech Nationalist leader, that these troops (who were still fanatically, anti-German) should be evacuated via Vladivostok. In the summer of 1918 they were thus scattered along the whole length of the Trans-Siberian railway, on their slow journey towards the Pacific.

Fierce anti-Germans, disgusted with the Brest peace and isolated by their language from any contact with the Russian people, these men were ready weapons, for the fomentors of civil war. The bargain was soon struck, and in the month of June practically every, Siberian town where there was a Czecho-Slovak detachment was occupied by them, and the Soviet was overturned. The workers were unarmed and the Siberian peasants, being mostly fairly well-to-do, quite apathetic. The White coup came off without difficulty, and in the Eastern provinces of Siberia was aided by the Japanese and Americans who were in occupation.

From motives of prudence, this victory was not followed at once by a restoration of the Romanoffs. A careful show of democracy was made, and moderate Labour men, of the Social Revolutionary Party, were installed. A rump of the dissolved Constituent Assembly met at Ufa, in the eastern part of European Russia. Local government fell everywhere into the hands of the Zemstvos (“democratically” elected County Councils). The All-Russian Directorate, appointed by the Assembly, and sitting at Omsk, contained a majority of Social Revolutionaries. During this period a careful moderation was shown: Bolsheviks were imprisoned rather than shot, and the White authorities carefully dissociated themselves from the sporadic outrages by the Czecho-Slovaks.

By November the time was felt to be ripe for the full programme. On the 18th of that month Admiral Alexander Kolchak, Minister of the Army and Navy, arrested certain of his colleagues, and proclaimed himself Supreme Ruler, with the supreme authority previously exercised by the Tsar. The “constitutional authorities” made no resistance over nearly all Siberia; certain of the less intelligent “democrats,” who had taken their own theories seriously, paid for their stupidity with their lives. A full-blooded, “White” policy was at once started. The organs of the town workers—trade unions, etc.—were ruthlessly suppressed, and the leaders murdered. The régime of flogging and murder which we associate with Horthy’s name, was anticipated by Kolchak and his assistants, Feodosieff (manager for Mr. Leslie Urquhart, of the Russo-Asiatic Corporation) and General Knox, representative of the British Government.

Kolchak then turned to the next point in the capitalist programme. Over all Siberia were posted notices and proclamations calling on ex-officers to enlist in his service. Soon he had around him a considerable and well-disciplined White army, amply, and indeed over-supplied with every kind of munition by the Allied authorities. Rapidly the irregular guerilla warfare which the Soviet had carried on with the “Constituent Assembly” in Ufa took on a grimmer character. The irregular Red bands which had previously defended the Soviet areas became lamentably inefficient. By March of the next year the Soviet forces were beaten. In spite of gallant recoveries they had been driven out of the vast mining areas of Ekaterinburg and the Urals. Kolchak had broken into European Russia and got a firm foothold there. Isolated revolts inside Siberia had met with bloody defeat.

Superhuman efforts were being made by the Russian workers under Trotsky’s leadership, to stem the advance of Kolchak. The substitution of a regular disciplined army for the irregular bands of the old days was in full swing, and was but little hampered by the foolish opposition of the Anarchists and “Left S.R.’s” who regretted the old roving groups of propagandists and (frequently) brigands. Moreover, as Kolchak advanced and was forced to augment his army by the inclusion of peasants and workers, there was hope of revolts.

A hope for many months frustrated. Each time the raw recruits of Trotsky met the White brigades the were broken. How could mere untrained workers face the famous Kappel brigade, the elite of old Russia? All through the spring the Russian workers were driven back, not by miles, but by great slabs of territory of a hundred miles and more. Ufa—Perm—Orenburg—Uralsk—one after another towns and villages which had been in the hands of the workers and had flown the Red Flag vanished in the dark flood of Kolchak’s advance. One week a town would be lost, next week it would be far in the enemy’s territory, and another stronghold of the workers be trembling on the edge of destruction. No other army could have stood the monotonous series of defeats which the Reds suffered, and yet have remained an army.

April came, and Kolchak was no longer a threat but a present disaster. Firmly in possession of the River Kama, (a tributary of the Volga) his troops and his British armoured steamers were threatening the great centre of Kazan, Russia’s Bristol, as well as straining up North to join the British troops in Archangel, who were pressing down to meet them. But in the centre was the real danger. Here Kolchak was at last in sight of victory. The River Volga makes an enormous bend to the east at the town of Samara, and this great corn centre was nearly in his grasp. Once his troops were in the town, the River Volga, Russia’s great means of transport since the railways were ruined, was closed. No more corn ships would go up to hungry Moscow. Instead, Kolchak’s troops would link up with Deniken on the Don, would receive tanks, aero-planes and officers from Western Europe. Then it was only a question of weeks before Moscow fell and the Soviet Government met the fate of the Paris Commune.

Kolchak pressed on gleefully. His centre, led by the famous Kappel and Izheff brigades thrust down towards the Volga. The defence seemed to be tiring and weakened. Some time in the third week of May (1919) his troops were under the walls of Samara. Leslie Urquhart’s agents smiled in Omsk, and telegraphed the news of Samara’s fall, the death knell of Russia, to the London papers.

They were too hasty. The Communists whose dead bodies marked the track of Kolchak’s thousand-mile advance had not died in vain. Trotsky’s armies, led by Kameneff, were not the old Red guerillas. Kolchak was in a trap. His centre—his elite—had thrust their way too far towards Samara. Down on their sides, from north and south, descended the Red armies, like the blows of a knife. The sides began to sag, to cave in: the troops descending on Samara stopped, saw their line of retreat narrowing. The village of Belebei should remain historic as the place where first the sides of the Kolchak triangle broke down. Instantly the centre dissolved into a mass of frightened, disorganised troops. The famous Kappel and Izheff brigades became a mere mob of hysterical, agonizedly terrified, fleeing men, fighting and trampling their way through the ever-narrowing corridor which led to safety and their base.

Diterichs, Kolchak’s Commander-in-Chief, hurried up. It was a heavy blow, but perhaps it could be recovered. The line could be reconstructed at Ufa, along the river. But Kameneff was not willing to wait. The Reds pushed on, blow after blow. They followed on the heels of the retreating Whites, right into the town of Ufa. Three days they fought in the narrow streets of that mountain town, and in the end the river was crossed and the Whites flying again.

The fall of Ufa ended the offensive period of Russian native capitalism. It had fought before Samara for victory. Now it was to fight for its life. Kolchak’s centre disappeared. His left—southern—army retreated south, its Cossacks wanting to defend Orenburg and their native steppes. Here it was followed relentlessly by the Reds. They pressed down south to the town of Orenburg; and there found the Red Flag still flown by the Orenburg Town Soviet, a lonely little island which had stood out above the surrounding flood all through the Kolchak invasion. Again the Cossacks fell back—into Asia, into the Aral region. Here they found coming up behind them the forces of the Tashkent Soviet, which had maintained itself ever since 1917. This was the end: they surrendered.

But Kolchak’s northern army was still intact. It could hold the Ural passes west of Ekaterinburg and protect the Supreme Ruler while he reorganised his army. Again, they could not hold the line. Kameneff’s men outmanœuvred and outfought them. The passes were taken easily, the White armies fell back in disorder. The Red troops had broken through into Asia: the Red Flag had climbed the Urals and descended on the other side.

What was happening, many of us asked then, in the vast plains of Siberia? As the Red troops covered league after league in pursuit of the Kolchakists, going ever farther into unending prairie, as the roads and railways ended, leaving only the one single line of the Siberian railroad—each step they took to the east separated them farther from their base and brought a new hope to Kolchak.

They were not very far from Omsk, when Kolchak decided that they were far enough from their base to make victory possible. Quite suddenly the Whites’ retreat stopped: their ranks stiffened. The Reds were trying to encircle Omsk and so had to fight on the outer lines, while Kolchak had the inner. His plan was well drawn up; but he had forgotten one thing—his men would not fight. They deserted, and the Reds swept down on Omsk. Inside the town there was panic and a frantic rush to the east. Kolchak (January 5th, 1920) signed an abdication. He fled east, his officials and troops following and scattering. His treasure was looted by the Czecho-Slovaks. Somewhere, and by someone in this ghastly wreck, Kolchak was killed. A few refugees, under a bravo called Semenoff, reached Mongolia. The Red Army followed slowly, and in the spring of 1920 a small detachment hoisted the Red flag again in Irkutsk. The greatest military effort of the Russian bourgeoisie had ended in disaster. The worst military danger ever run by the Soviet was over.

After Kolchak’s defeat in May the Soviet Republic had to turn its attention to the South. Here Krasnoff had been repelled but not crushed, and his place was taken by Denikin, who with liberal British Government aid, had been able to raise a large voluriteer army of Tsarist officers. With these he first cleared the North Caucasus of the Red Guard, and then entered the Don region, passing thence to the Ukraine.

In this province, on the retreat of the German armies after the German Revolution in November, 1918, the Red Guards had established the Second Ukrainian Soviet Republic. This was overthrown with barbarities by the advancing Denikin, who, pressing northward (with assistance on the West from Petlura, the successor of Skoropadsky, from Yudenitch, the successor of Von der Golz, in command of the Balkan Junkers, from Balakovitch commanding the White Esthonian bands, and White Guards operating from Finland), was able to threaten both Petrograd and Moscow. Returning from the overthrow of Kolchak, the Red Army meeting him all along the line, hurled Denikin back into the Crimea, taking Odessa and establishing the Red Flag again on the waters of the Black Sea.

Denikin retired to England to be pensioned, leaving the wreck of his forces to be reorganised by Wrangel.

Yudenitch was defeated, and, despite Allied pressure, a peace was concluded with Esthonia.

Kolchak, emboldened by Denikin’s successes, had made his last effort, had failed, abdicated, and died at the hands of victims of his barbarity.

The Allies, faced with a world crisis consequent upon war ravages and the general unrest of the toiling masses, one by one withdrew their armies—the process being accelerated by a series of mutinies.

Shortly after the second anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, it seemed that Soviet Russia would be free alike from Imperial and counter-Revolutionary armies, and left to concentrate its attention upon peaceful construction.

The hope was doomed to disappointment. The Polish Whites, under pressure from French and British finance-capitalists, refused all overtures for peace and, their equipment renewed, returned to the attack. The Ukraine was again over-run, and once again the Red Army had to face its foes. Taking advantage of the Polish successes, Wrangel advanced from the Crimea. The Red Army was again successful. The Polish forces were driven back almost to Warsaw; Wrangel being held in check by a relatively small force.

Again British Imperialism intervened. The Soviet Government was threatened with War should it dare to take Warsaw; munitions were rushed to the aid of the hard-pressed Poles; more would have been sent but for the refusal of the workers in Italy, France and Britain to countenance their transport. Lord Curzon appealed to the Soviet Government to allow Wrangel to retire unmolested.

All demands were complied with, and a peace seemed possible, when an unexpected rally of the Polish forces inflicted defeat upon the Red Forces. The defeat was of no great moment beyond the fact that it involved a retreat along a somewhat lengthy line. It seemed more serious than it was, and Wrangel, heartened by the news, threw aside all Curzon’s promises of good behaviour on his part to make one more bid for Imperialism. This time there was no hesitation; the Red Army hurled him back to the Crimea, and the Communist battalions, with reckless heroism, burst through the “impregnable” entrance into the Crimea at Perikop, and chased the last relics of the last of the “constitutional armies” over the sea.

In the meantime, the pressure of economic dislocation, combined with proletarian unrest, had forced the Allies to abandon their contemplated war upon Russia, and Poland was perforce left with no alternative but to make peace.

On December 19th, 1920—a little over three years from the Soviet revolution, the Soviet War Commissioners announced to the world that their War communiqués would cease, because there was no more war within the frontiers of the Soviet Republic.

Three years of counter-revolutionary strife, following upon three years of imperialist war, left the Russian people with the Soviet authority established over an exhausted people.

It is necessary, in order to understand how exhausted, to turn to the internal affairs of these three years and trace first the stages of the consolidation of the Soviet Power, and secondly, their accomplishments in social construction.

It was first necessary to create a machine of political co-ordination in order that Russia might become a unified whole instead of a chaos of communities, each with its different degree of economic and social development.

The Soviet system had to be co-ordinated, the local Soviets grouped into a hierarchy of district and provincial Soviets under the direction of a central executive council of Commissars. As these Soviets would be each in their degree both legislative and administrative bodies, it was essential to secure a uniform direction to them all. A party-struggle for leadership in the Soviets between the only parties left with any hold over the working and peasant masses was therefore inevitable.

First of all the Soviet authority had to be unrivalled. The dislocation of the period between the March and November Revolutions had shown the impossibility of a dual control of Soviet and Central Executive. The last effort of the Kerensky régime had been to, at last, summon the Constituent Assembly. Every effort was made to prevent the Bolsheviks and their allies from securing election. This notwithstanding, the elections (on November 25th, 1917) resulted in only a small majority for the counter-revolutionary block as against the alliance of Bolsheviks and Left Social Revolutionaries.

To meet this situation the All-Russia Soviet (now proclaimed the ruling authority in Russia) drew up a declaration of the rights of the Toiling and Exploited Masses, which they proposed to present to the Constituent Assembly. This declaration, if adopted by them, would have merged them as a body in a Great Convention of the All-Russia Soviet Congress with additional delegates of the trades unions and co-operative societies, which had been summoned to adopt a constitution.

The Assembly met; the Soviet parties (Bolshevik and Left Social-Revolutionaries) numbering 40 per cent. of the whole Assembly. The declaration was presented and rejected by the majority. The Soviet minority thereupon withdrew in a body to the Convention, and the anti-Soviet rest of the Assembly was ordered by the officer of the guard to go about its business.

Much has been made of this “suppression of a democratically elected body” as though it were a trampling by an armed minority upon the rights of a liberty-loving but unarmed majority. The answer to that is given by the history recounted above. The Assembly was not an expression of anything beyond the superior propaganda resources during the Kerensky régime of the Aristocratic Kadets, the Middle-class Mensheviks, and the agricultural bourgeois Right Social Revolutionaries. As for the majority being unarmed, and the minority along armed—the only armed support the Soviets could command came from that section of the rank and file of the army and the fleet which was prepared to support them in defiance of their superior officers and those of the workers and peasants who had managed to secure arms in the course of the previous revolutionary upheavals. The regularly organised Bolsheviks and Left Social Revolutionaries together were, it is true, but a minority; but so, too, were the Kadets, Mensheviks, and Right Social Revolutionaries. Two minorities, a revolutionary and a counter-revolutionary, were struggling for the leadership of the mass of the population. Neither the Soviets nor the Assembly had behind them the force of long established tradition—except so far as the Soviets were connected in the mind of the masses with a heroic struggle against oppression.

The Soviet decrees upon peace, land, and labour control settled the matter for the overwhelming mass, and the Assembly, still-born, lingered on the scene ever more clearly an instrument for imposing the will of alien and would-be privileged exploiters upon the self-emancipated mass.

The Constituent Assembly dispersed and a Soviet Constitution adopted, it was imperative to turn attention to matters economic.

Here, from the first, the bitterness of class-conflict became manifest. Left to choose their own line of advance, the Soviet Commissioners would have preferred to proceed by the establishment of a State control and direction over the then existing capitalist enterprises in Russia—a control analogous to that which war-necessities had brought into every Capitalist State.

The decree giving the workers control over industry, for example was a rough and ready way of establishing State ownership of them means of production, and in practice was quite compatible with leaving the capitalist ex-proprietor in charge as a manager paid by his people.

The infuriated bourgeoisie, however, were not going to allow anything so simple as that. They, acting through the banks (only the State Bank was at first taken over by the Soviet), proceeded to organize a general strike of managers, intellectuals and functionaries throughout Russia. For a time factories, public works, hospitals; food committees, and railways were all brought to a standstill by this universal sabotage. The Soviet, therefore, was compelled to commandeer factories, take possession of the banks (which were under the instruction of the counter-revolutionaries and with secret Allied support paying strike pay to these revolters), and bring pressure to bear upon the indispensible functionaries to induce them to return to their tasks.

So much has been said of “Bolshevik tyranny” that one marvels to read of the mildness of their procedure. A bread card stopped; a striker imprisoned until he agreed to return to his duties—such are the measures employed.

Even when Krasnoff, Kerensky, and the others were making their armed assaults upon the Soviet Power, and moving all the Allied earth for arms to overthrow the commissioners, the newspapers of their respective parties were appearing in the usual way, and their friends were bribing, the newsboys to boycott the official Soviet journals.

Not until the German advance, and the excitement following the enforced Brest-Litovsk peace, did the Soviet State in its agony have recourse to the weapon which its enemies consistently employed against it.

The crisis after Brest-Litovsk, the most serious internal strain to which the new Proletarian State was subjected, came from the frantic anger of the Left Social Revolutionaries, first at the loss of the Baltic Provinces, then at the German-aided bourgeois atrocities there and in the Ukraine, and generally at the fear of the growing power of the Centralised State.

Lenin and the Bolsheviks had agreed to the Brest-Litovsk treaty because of the necessity of securing a breathing space for constructive work—particularly economic.

This necessity was taken every advantage of by the bourgeois opponents of the Bolsheviks to secure by sabotage, insurrection, and invasion the overthrow of the proletarian régime. The Left Social Revolutionaries, impatient at the growth of the State Power, took the occasion of the Brest Peace to denounce the Bolsheviks for “compromising with capitalism.”

Faced with enemies from Left and Right, the Bolsheviks hit out at their enemies. An Extraordinary Commission was established to combat sabotage and counter-revolution, and systematic methods adopted for the defence of the young State in its critical formative years. Taking their stand on the obvious facts of the situation the Bolsheviks applied the only weapon left them, that of the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.

When, shortly after Brest-Litovsk, the German ambassador was assassinated in Moscow by angry S.R.s—an attack was made by Right S.R.s against the Soviet Commissioners, Volardarsky and Uritsky were murdered and Lenin wounded—it was at first thought fatally.

The Extraordinary Commission and the Soviet authorities replied by proclaiming a mass terror against the enemies of the Revolution.

Upon the details of this we have no need to dwell. The whole country was in a chaos of conflicting passions, and the enemies of the Republic had shown themselves utterly without scruple in their determination to compass its downfall. The Soviet Republic had no choice but to cast sway scruples, like-wise, and deal with wild beastlike attacks in the only possible way.

While the civil wars continued, and leading Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries were active in directing the armies of invasion, it was obviously impossible for tolerate within the Soviet frontier any public activity of the parties of whom they were the directing heads. They were, therefore, subjected to much the same treatment as they had themselves dealt out to the Bolsheviks in July, 1917. This repression, too, on occasion, entailed the dissolution of sundry Soviets in which they had managed to gain a footing.

But when all possible is made out of it, the “Red Terror” which the Bourgeois World has combined to paint as a period of black and brutal tyranny, amounts to little more than the dictatorship exercised by every Capitalist Government during the war period. Certainly both in the nature of the restraints and the number of executions the Terror stands as mildness itself when compared with the Black-and-Tan régime in Ireland or the Horthy terror in Hungary.

What made it all the more imperative that the political chaos should end was the appalling state into which industry had fallen.

Not a single branch of industry, a single railway, or a single factory which passed into Soviet control on the November Revolution but was disorganized or on the point of collapse.

What war and social dislocation had failed to do, sabotage completed; and the Soviet Commissioners had to set to work to buildup the entire economic life of Russia all over again.

Two things must be remembered—Russia had always imported raw materials and machinery from Europe, and secondly, the industrial North depended for its existence upon fuel and food from the East and South.

Whenever possible the counter-Revolution cut off Moscow—(to which the Government had been shifted when the German advance threatened Petrograd)—and the North from food and fuel. This they were able to do for long periods during which the workers were compelled to leave the factories to join the army.

Under these circumstances very little would seem to have been possible. Much, however, was done by using the growing discipline of the Red Army, supplemented by an educational campaign without parallel to supply what was lacking in the technical knowledge and economic co-ordination of the working mass available, marvels were done in the way of increasing the output, restarting factories, and bringing the whole of production under a central direction. But even so, the results were appallingly short of what was needed.

Not only were they hampered from lack of machinery and materials, but all the time they were faced with the terrors of a food shortage.

The aim of the Bolsheviks from the outset was to establish a co-ordinated system of Communism. This they knew well enough, being the Marxists they were, must rest upon a basis of completely co-ordinated social production. Their first endeavour had to be to secure this co-ordination. And, first of all to be faced, was the problem of food supply.

Because Russia had been a food exporting country in the days of the Tsars, it has been supposed that Russian agriculture was in an advanced condition. The facts are quite otherwise. The corn exported in those days represented not Russia’s Power to produce in excess of home needs, but the extent of the exploitation of the peasantry. Often while food was exported there was famine in the peasant areas.

The first step of the Soviet Republic made them world-famous. Decreeing a government monopoly of bread, they firstly forbade all private trading in grain, and secondly, issued a bread ration graded in proportion to the social and working usefulness of the holder of the bread ticket. “Those who will not work shall not eat,” received a literal interpretation at their hands.

It was, however, one thing to decree a government monopoly—another to enforce it.

Had they been able to receive the normal supplies of raw materials, machinery, and auxiliary materials of which they stood in need, the Soviet Government could have fast of ensured their monopoly by giving indispensible articles in exchange for the peasant’s corn. The Allied blockade, as it was designed, prevented this. The counter-revolutionary war cutting them off from minerals, fuel, and raw materials still further curtailed their bargaining powers, and all but entirely prevented the building up of big scientific farms worked by communal co-operative effort with adequate appliances. The Soviet Government had little material to offer the peasantry—and the peasant was in most cases too ignorant to see the advantages to be gained from helping the Communist Republic into being. A policy of food requisitioning had to be adopted to obtain sufficient for the needs of the Red Army and when the peasant sought to evade the tax by hiding his grain, drastic measures were at times adopted to seek it out. Private trading, too, was difficult to stop, because of the immense amount of domestic industry still carried on in Russia, and because the appalling difficulties of intercommunication made it impossible for the Central Government to actively supervise the doings of every locality.

Within their limits they did what they could. A rough and ready Communism in consumables was established. What food there was was distributed, if not equally, at any rate equitably. The children being given preference even over the arduous worker. Milk for nursing mothers, commandeering of surplus furs for the use of proletarians and soldiers, rationing of house accommodation—all things were done to secure the maximum of good out of what there was to use.

And all the time through the schools, special propaganda tours, leaflets, wall posters and free, distribution of books, a campaign against the time honoured ignorance and illiteracy of the Russian masses was waged with a vigour not surpassed by even the Red Army itself.

The Railways had collapsed even under the Tsar. In the Kerensky régime they grew even more dilapidated. Only the relics of a railway system passed into the hands of the Soviet régime, and even those were still further impaired by the counter-revolutionaries, who destroyed bridges, culverts, and stations whenever possible.

Kolchak, among other villainies, destroyed a large part of the shipping of the Volga, while, wherever the counter-revolutionary armies passed, carts and horses were requisitioned or destroyed. The efforts made to repair the Locomotives, the track, and transport generally have been heroic.

Noteworthy in this connection were the efforts (during 1919 and 1920) of the Communist Party. A great campaign of Voluntary Saturdays was initiated. The Communist Party members made it a point of duty to spend their Saturday holiday, upon some urgent task in railway repairing or in some kindred work, the effort being under the supervision of skilled directors and all given voluntarily as a loyal contribution to the well-being of the State. Many non-Communist workers shared in the effort—and its effect was undoubtedly great.

Noteworthy in this connection were the efforts (during 1919 and 1920) of the Communist Party. A great campaign of Voluntary Saturdays was initiated. The Communist Party members made it a point of duty to spend their Saturday holiday, upon some urgent task in railway repairing or in some kindred work, the effort being under the supervision of skilled directors and all given voluntarily as a loyal contribution to the well-being of the State. Many non-Communist workers shared in the effort—and its effect was undoubtedly great.

When, in 1920, there seemed an end of war, the Red Army was transferred from the Military to the Economic Front. In all essential tasks, wherever it was materially possible, the Red Army was converted into a disciplined labour army. Particularly in big farming operations was this magnificent force converted from a machine of military offence into one of life maintenance.

This was interrupted by the Polish War and the adventures of Wrangel; both of which occurred at a season which caused the loss of much of the results of their efforts.

The harvest of 1920 was bad—partly because of the depredations of the Poles and their ally Petlura, and partly from sheer lack of transport.

Inside the Party everything was canvassed and discussed with the freedom of men for whom such a thing as personal rights had ceased to exist—the only thing at stake being the commonwealth.

When it was necessary to strengthen the Red Bands, Communists were selected by their comrades for the posts of dangerous honour. When the Red Army was formed by the co-ordination of the Red Bands and by levies on the personnel of the factories, Communist nuclei were drafted into every battalion and unit. Later special Communist companies were formed whose duty it was to lead in every moment of danger. It was these Communist companies who achieved the impossible in storming the “impregnable” Perekop and putting an end to the adventures of Wrangel.

Similarly into every factory when the output was falling off, and into every post of industrial difficulty Communists selected for their capacity were drafted to do under the impulsion of the Communist faith what no one had been able to accomplish from pressure of mere material obligation.

Into the villages where the food supplies were falling were Communists selected for their knowledge of peasant psychology and of agriculture; or failing that, for their ability as educators.

Into the villages where the food supplies were falling were Communists selected for their knowledge of peasant psychology and of agriculture; or failing that, for their ability as educators.

In every way the Communist Party acted as the soul of the Russian Proletarian State. They were, of course, traduced as spies, as hirelings alternatively of the German and of Allied Imperialism. Especially were they the victims of world-wide denunciation when they were able to expose and defeat the cunning schemes of the counter-revolutionaries to swing either district, workshop or trade union Soviet into antagonism to the central political and economic organisations.

We have noted their work in connection with the Communist Saturdays—when it is remembered that this was done by men who from the Revolution have never had anything like what we are used to regard as enough to eat, who varied exhausting toil in the factory with reckless heroism in the battlefield, and both with devoted labours for the education of the more backward masses, some idea is caught of the moral grandeur reached by the Russian Communist Party.

From the nature of things it was inevitable that to produce this effect they must be as carefully selected as was Cromwell’s New Model.

This has been made the pretext for describing them as an “oligarchy.” But their accomplishment in bringing the wreck that Tsars and Kerenskys had made of Russia into its present cohesion and regulated advancement is the answer to all suchlike taunts. No other body of men have ever succeeded in both pursuing their ideal and modifying their mode of approach in accordance with every freshly revealed obstacle as these have done.

Particularly have they succeeded in building up a system of producers and consumers Soviets to fuction as the economic machinery of the Soviet State side by side with the Political Soviets.

The more peaceful progress is granted them—the more their industries develop—and they need only the initial help of tools, machinery, and technical tutors to enable them to commence such a progress—the more the econmic Soviets willdevelop, less and less important will grow the political ones, and Russia will pass from the stage of Proletarian Dictatorship into the classless solidarity of the Communist Ideal.

The last shot which was fired in the Crimea did more than destroy the hopes of Wrangel’s armed White Guards. At one time it seemed as though it had been fired into the body of the Soviet Republic. For with peace came the most difficult period of the Russian Communists. They had to create a peace economy. They had to refound industry and agriculture on a peace basis. The rough and ready “military Communism”—the requisitionings and arbitrary centralisations—which had been enforced by and accepted because of military needs, had to end.

The first thing which had to be done was to disengage the State from the aggregation of small factories and small industries, as yet unsuitable for nationalisation, which had been taken over as part of the war on the bourgeoisie. The enormous apparatus which this had involved had permitted the growth of bureaucracy—first scented out and denounced by the Communists themselves. The State was incapable from the lack of raw material, of keeping them going. Therefore, many lesser factories were leased for short periods to workers’ societies, co-operatives, or even (under strict safeguards), to private individuals. This was inevitable, but obviously needed careful watching. However, the main industries, including all such key industries as transport, remained under Soviet ownership, and as before were run in effect by the trade unions concerned under State supervision—a form of Guild Socialism more real than any that “Building Guilds” are likely to bring us.

But the supply of materials, particularly mineral raw materials, was more difficult. No Russian authority could adequately exploit the mineral resources of the Donetz, Caucasus, and Urals if the Soviets could not. Capital—meaning the machinery and resources to start the oil wells and mines again—had to be sought elsewhere and the test of the world was capitalist still. Faced with necessity, the Soviet bowed, and the policy of strictly limited concessions was adopted.

The object of all this was to restart production. They were, it is true, theoretical retreats from Communism, but enforced retreats. Communism can only be based on increased production, and production could not be restarted without foreign machinery. If the European workers, in particular the British, had had the courage to emulate the Russians—but what is the use of dreaming? They had not, they had failed and the Russians paid the penalty.

Agriculture represented a terrible problem. Agriculture, like every industry, had to be stimulated enough to enable the products necessary for a Communist régime to be produced. In addition, the peasants had signified not uncertainly to the Workers’ and Peasants’ Government that they wanted free trade in corn. Thus the policy of a fixed food tax instead of a seizure of all surplus corn was adopted and with it went the inevitable recognition of free markets. At once the peasants began to sow more and production began to rise.

This abandonment in places of war semi-Communist measures had this danger—that it might encroach on the reality of workers’ control. It was a ticklish business, but the Soviet Government was carrying it through, and the increased production began to bring nearer Communism—the quieter period we had all dreamt of, the land of William Morris, of liberty, freedom and ease.

And then—disaster. The ravages of the Whites had prepared it, but none the less it came suddenly. The sun brunt the vast plain of the Volga provinces, the crops disappeared. Famine faced twenty millions. Such an appalling catastrophe would have overturned any government. We cannot yet say that the Soviet is safely though: we only know that if anything could survive, it will.

Once again the cup has been dashed from the lips of the Russian worker. How long is he to be forced to stand alone, the vanguard of the world’s workers, alone fighting for the proletariat?

How long can he stand alone? How long before we join him?